“What debts—monetary, emotional, filial—did my parents have that I’ve inherited?”

August 25, 2021

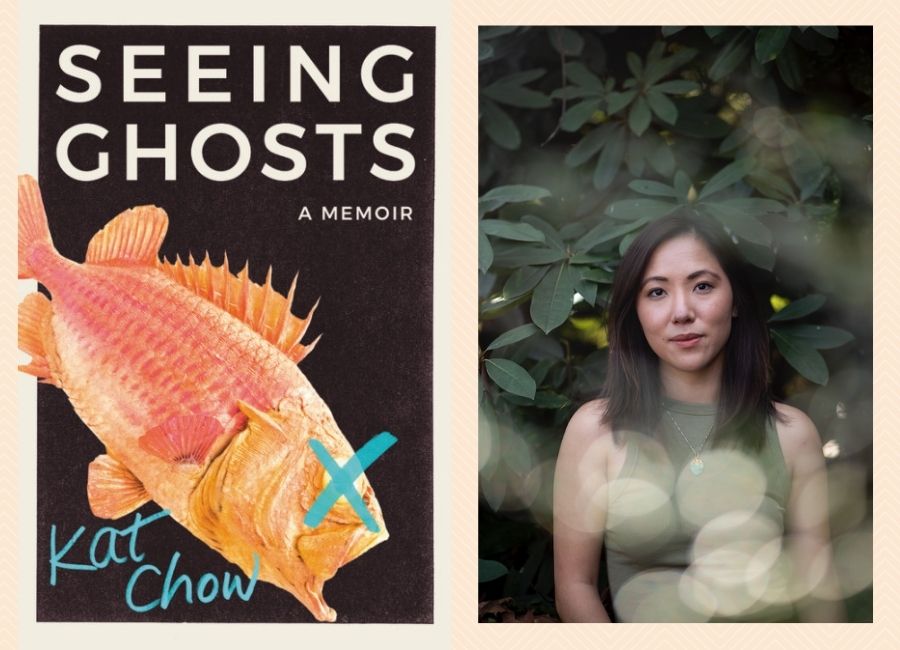

“I conjure you from the underworld, part taxidermy, part ghost,” Kat writes to her mother in Seeing Ghosts. “I spin you out of myself and into something else.” The act of preservation and a desire for knowability haunt this debut memoir, which is structured around the death of Kat’s mother and the many loved ones she left behind. What emerges from Kat’s heartfelt searching is the portrait of a family for whom loss becomes a second language.

Many readers will recognize Kat’s work from NPR’s Code Switch, where she covered topics ranging from the history of the term “gaslight” to the ways in which the model minority myth sustains racial divides. Seeing Ghosts brings Kat’s journalistic eye to the excavation of her own family history. As readers, we journey alongside her as she reconstructs her mother’s childhood in Hong Kong, her paternal grandfather’s life in Cuba, and her father’s extraordinary efforts to recover his body despite decades of separation. Throughout it all, we are drawn to Kat’s ability to bring her family members to life with trademark humor, tenderness, and human fallibility. “Grief is a container of contradictions,” she states. The same can be said of the characters who populate our lives. Seeing Ghosts explores the ways we cope with loss through one family’s attempts to move forward while continuously remaking the past. Kat and I corresponded about Seeing Ghosts over the month of July.

Jen Lue

Much of the book is addressed to your mother, as a private conversation that the reader feels privileged to listen in on. When did you come across this form for the memoir and what did it do for you in writing it?

Kat Chow

I’d taken a short fiction class with Danielle Lazarin years ago, and I wrote a story that used that form of address to a fictional sister. I loved how the use of you made my writing snappy and propulsive, and it allowed my narrator to be messy in her misunderstanding of her sister. It was a way for my characters to reach across an expanse to communicate something, even if so much was ultimately left unspoken.

I took this with me as I wrote Seeing Ghosts. I remember a stretch of months where I’d be in bed at four a.m., furiously typing into my notes app any details about my mother that I remembered, or questions about her that I might never be able to answer. I was carving out the limits to which I could make my mother known and I kept thinking, there is something missing there is something missing there is something missing.

At some point, I realized that I needed to write into that uncertainty. I wrote a very early partial draft of the book addressed to my mother. Later, I wound up paring it back and using the direct address more intentionally, in order to invoke my mother’s taxidermic ghost and the ways memories linger and haunt us. I wanted the use of you to serve as a narrative form of preservation, taxidermy, and resurrection—pulling someone back to us, and trying to recreate them in memory.

And—this shouldn’t give anything away—the direct address returns in a final section of the book, oriented toward my father, who is very much alive, though perhaps ghost-like in our understanding of one another. I loved putting this in the final section, because it added to this arc of emotional movement that I’d been trying to illustrate—a softening, despite the distance and uncertainty, and most importantly, an acknowledgement of the messiness of it all.

JL

Your memoir includes a lot of intertextual references to works by poet Diana Khoi Nguyen and scholar Anne Anlin Cheng. It creates an instant conversation with these contemporary works that I feel like many memoir writers (my old MFA program included!) are warned to stay away from because it veers away from the strictly “personal”, first-person narrative experience. Did you encounter any resistance in including their words in Seeing Ghosts? How did you approach preparing for and researching for this book in general?

KC

I’m always falling down these rabbit holes—or I guess, rabbit abysses? bear dens?—of research whenever I write. I let myself get lost in archival newspapers, scholarly articles and books, contemporary literature, poetry, documentaries, old diary entries, family records, interviews—you name it, whatever I can get my hands on.

Maybe I’m this way because of my foundation as a reporter, or maybe this is very normal to most writers’ processes, but I’ve always been fascinated by the history and context that informs a place or person. The questions I kept asking myself were key: What do we owe? Is writing a form of taxidermy, preservation, and/or exorcism? What has my family lost and gained?

In the sections, for example, about Hartford, Connecticut [where my family lived] I reached out to a couple professors and the head of the Cedar Hill Cemetery, and I worked with the journalist Claire V. Tran for research help in pulling information about Hartford’s demographics as it related to housing and race. I read poetry and contemporary memoir, and for a couple drafts that I’m sure concerned my editor, this book had a ton of footnotes, so I read fiction that worked with footnotes, mainly a bunch of Borges.

All that being said, it was not a tidy process. But I never received pushback for including contemporary works in this book and I’m relieved I didn’t, because my approach has always been a bit maximalist.

JL

Towards the end of the book you write, “What is grief, if not the act of survival?”. There is something about the act of persistence in writing this memoir that feels both necessary and heartbreaking. Did you encounter any roadblocks in doing research for this book—especially when it came to speaking with family members—and if so, what helped propel you forward?

KC

My family was incredibly open and generous with interviews. I thought there’d be things that would be off-limits—I thought, especially, that talking about my mother might be too painful for my direct family. But my sisters and dad just seemed so proud that I was doing this thing I’d been circling around for years, and I think they were relieved to finally share memories or what they’d been feeling.

My dad in particular got a kick out of this process. Seeing Ghosts gave us a reason to talk through the distance that had grown between us. I mean, let me be real: there were many times where I’m sure he found my questions tedious, and we cut our calls short because we’d fallen into our old dynamics.

I sent him a copy of my final draft and he sent me an email with the subject line “Book Review.” The body of the email was a list of page numbers and little notes—that he was in the car in a certain anecdote, that his kitchen counter was made of formica and not linoleum. At the end of his message, he wrote something like, “Good luck with the book. Love, Daddy.” And that was that. The fact that he took so much time for such a close read really meant something. His value of independence—well, it’s your life!—probably comes into play here. So much of crafting this book was in talking with my family and distilling their stories into just one narrativized version of our lives from my specific perspective, and one slice of my perspective, too. They recognized this as well, which was freeing.

JL

When I think about Asian American narratives, I’m often fixated by characters’ wants and needs, which can be at odds with the dominant culture or else suppressed and deferred. There’s one line that refers to your parents and “the way in which their needs in life had slipped beyond notice.” I was also moved to hear about your father’s various ventures into raising angelfish, sailing, amateur taxidermy, etc. and their abandonment.

I wonder if you could riff a bit about what you see in your parents’ wants and needs and how those might differ with your own.

KC

That distinction between wants and needs was something I was really working through in the text. The difference between my parents and the ways they were oriented toward joy and survival, and how their own upbringings and experiences of loss with their parents shaped them. Both of my parents, always wanting more in their various ways, at the expense of themselves or others. I chose to include stories that allowed their playful sides to emerge, gave them space for their idiosyncrasies (my mother pluralizing words and her invention of teethface, my father and his “normal” speaking voice), and showed what they were constantly reaching toward.

It did help that I knew from early on that this book was going to be about parallels. My editor, Maddie Caldwell, often talked about finding the ways my stories mirrored and paralleled my parents’, and that was a useful suggestion. Some of the mirrors I’d identified were between my mother and me being the youngest daughter, whose own mother had died young, and who was in turn mothered by her siblings.

The parallels between my father and me emerged in the form of questions of what to do with the bones or ashes of loved ones, and how to care for parents who were—in various ways—inaccessible. I quickly understood that this book was less about grief and more about loss in its many forms: of person, place, country, body, self, memory. There were so many more, of course, but I was interested in examining where those parallels broke apart.

JL

I love how explicitly your memoir talks about class. We find it in the disputes between your father and your mother’s family; in your family’s lifelong struggle to pay for household expenses; and in your father’s role as a landlord to predominantly Black and brown tenants in Hartford, Connecticut. When did you first become aware of how class functioned in your family story? How did you choose to weave it into the narrative?

KC

From the start, it was so important for me to write about the various ways race and class function around us—how capitalism manifests in our lives related to immigration, education, healthcare, property ownership, and even our ability to grieve and experience loss. I didn’t want to just come out and say all of these things, though—I tried very hard not to over explain anything related to race or class or how I make sense of my identity as the kid of immigrants from Hong Kong—and it was an exercise in finding the right moments to illustrate the tensions I wanted to show.

Throughout my childhood, class was described to me in terms of how my parents, and in turn, my sisters and me, could survive or thrive. When I was young, my parents had asked my grandfather for financial help, goes the story, but he refused, and said that it was my father’s family’s responsibility. My parents shuttered their restaurant and filed for bankruptcy, and my mother’s income primarily supported the family. We were stretched very thin. But in a rebellious moment, she bought a baby grand piano on credit to show her father that she didn’t need his financial help. She’d always wanted one, and to her, it was such a symbol of having made it.

It took years to pay off, and I think all of the adults knew she couldn’t afford it, though it mostly left my kid-self very confused. It took me years to understand that around that time, we were in so much debt—that credit cards were canceling my parents’ accounts, that even when she was sick, my mother was wary of doctors visits because of how expensive she feared they were, that she constantly confided in her siblings about her financial worries and how they were so overwhelming.

As I wrote Seeing Ghosts, I leaned on specific questions to tease out these ideas. I always need a question to anchor me when I’m writing—even if it’s the sort that can’t really be answered. “What do we owe?” and this idea of debt was one of the major ones I asked myself when writing this book. A mentor, Keith Woods, guided me toward it after reading some early parts. What do we owe each other, to the places or countries we’ve left, and to the new ones that are home? What debts—monetary, emotional, filial—did my parents have that I’ve inherited? Where did these debts come from, and how do we settle them, if at all? It was through questions like these that the hazy ideas I had around survival began to come into focus.

JL

When I think about your family history, I am reminded about the inadequacies of the archive (i.e. historical accounts, phone records, autopsy reports) to account for what happened to your grandfather after he immigrated to Cuba or to your mother’s body as she was battling cancer. The feeling of visiting your father’s village of Hoiping and feeling a recognition that’s “absent of memory or meaning” seems so central to the experience of many immigrants and children of immigrants. I wonder if you could elaborate a bit on your feelings about this.

KC

You know, this reminds me of something one of my sisters said when she read an early draft of this book. She kept repeating, I’m so grateful to have this family history recorded. She was learning so much about our family, just as I was through the process of creating this narrative.

Facing these archival materials and having to imagine the granular details of how my family experienced them—for example, my mother’s cancer diagnosis, or my grandfather’s life in Cuba—was another research challenge in itself. I could get close to a version of the truth—but I often lacked much else. And I think that’s why those details are so haunting, and why these people turned into ghosts. The what ifs? They stick with you.

I play with the idea of preservation in this book, as it relates to taxidermy and this childhood imagination of my mother as a ghost. How does one keep someone or something who is no longer alive with us? It’s in the memory itself: recalling it, speaking it, writing it. That’s partly why I love reading memoirs written by immigrants or children of immigrants. Trying to preserve history is such an act of determination and love. We as writers can become our family’s archives.