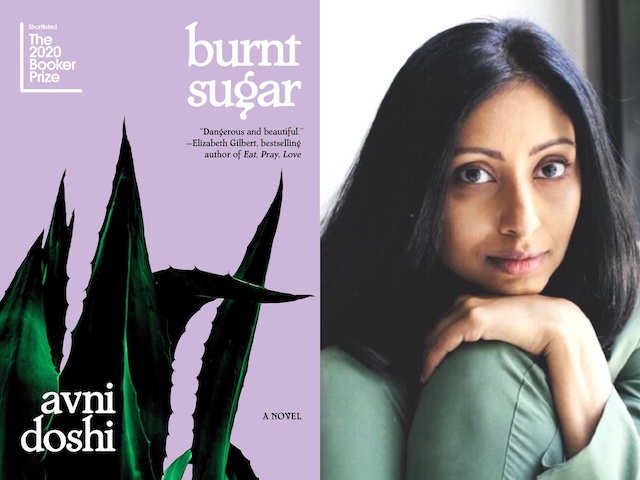

The author of Though I Get Home talks writing against censorship, non-traditional “immigrant stories,” and writing a novel to think through her life.

April 18, 2018

For the last seven years, YZ Chin has been living in New York City, working in the tech industry by day and writing by night. In Though I Get Home, her debut collection of linked stories, she delves into life in Malaysia, exploring the interplay of the personal and the political, how government policies affect individual choices, and realms where home and belonging don’t always intersect.

A young woman ventures to Kuala Lumpur for a political protest, and is imprisoned for writing an “inflammatory” poem. A young man travels home to reconnect with his Malaysian roots, only to find his efforts spurned because he is too American. A mother and daughter’s argument over sexuality unveils family secrets. An Olympic sharpshooter discovers his next protégé, the divine ruler’s concubine. As I wound through YZ Chin’s elegant prose, I’d find myself transported from the local to the global within the span of a few short pages, never questioning the ride. Though I Get Home won the Feminist Press’s Louise Meriwether First Book Prize and I can see why. It’s angular yet impressionistic, unsentimental yet uncannily moving, and a subversive take on the immigrant stories we’ve come to expect from “immigrant writers.”

YZ and I first met on social media, in a Facebook group for authors publishing books this year. We chatted online over the course of a day and a half about her book, which came out on April 10th.

—Mira T. Lee

Mira T. Lee: This collection kept defying my expectations at every turn. Some stories feel more like “traditional” immigrant stories, others feel impressionistic—almost surreal—and take us into unfamiliar territory, both in content and form. Tell me about the process of assembling these stories into a collection—did most of them already exist? Or did you write specifically for this collection? And how long did all this take?

YZ Chin: When I set out to write this book, I envisioned writing a novel. I was living in the U.S., working in the tech industry for immigration purposes. I was at a crossroads: Should I stay on in the U.S., which would require me continuing to work full-time as a tech worker for the foreseeable future, or should I return to my native country of Malaysia, where I could devote time to writing, but where the government regularly censors art? Instead of drawing up a list of pros and cons, or taking some other logical approach, I started writing a novel to think through my life.

I’ll have to try that next time I’m feeling at a crossroads! So the novel was about Isabella Sin, who shows up throughout the collection?

Yes, the first draft was about Isabella, the young woman taken political prisoner, as well as backstories involving her grandfather and parents. But because I was working full-time, the writing process was so slow and fragmented and I couldn’t get a sense of wholeness out of the draft. By the time I reached the end of the novel, the beginning already felt like juvenilia, because I’d changed as a person and as a writer. I revised twice, and it was the same each time. Eventually, I realized I didn’t want the book to have a unified tone. Because as you said, some stories feel more like “traditional” immigrant stories, and some don’t, and that was absolutely intentional.

It felt intentional. And the ordering of the stories felt intentional too, like it was vital to the flow of the book—like a well-crafted album.

Right, so when I realized my book wasn’t going to be a novel after all, I focused on salvaging the core story of Isabella, and adding other stories to mix up the overall style and tone. For some stories, I wanted to place different characters in somewhat similar situations, but explore how they would take completely different actions and go down opposite paths.

I noticed that you plopped the reader right into Malaysian culture and politics, with hardly any background information about the country’s history, ethnic/racial makeup, or current state of affairs. Did you have an audience in mind as you were writing?

When I published my very first story written in English, I excitedly showed it to my parents. Although English isn’t the language they use most, or even daily, my parents do speak English and read English newspapers. But after they read my first story, they told me they didn’t “get it.” And that was such a significant moment for me. I started seriously interrogating myself: who was I writing for? Do I want to write primarily for a Western or international audience, or for a Malaysian audience? And of course the answer is “both.”

I’m second-generation Malaysian and an immigrant to the U.S., with no family here. Of course I wanted to write an immigrant story. But I didn’t want it to be like an immigrant story catering to readers in the dominant culture, where the immigrant’s arc is coming to a new land, encountering either hardship or comical mishaps, and eventually fully or partially embracing the dominant culture. My book has some of that, of course, but I like to think that the immigrant characters also perform subversive acts that are big or small, taking something from that culture for their own—in the case of the story about Isabella’s grandfather, literally imposing his minority culture onto the dominant one when he stages a Chinese funeral for a colonial officer’s daughter.

Was there anything you particularly wanted a Western reader to learn, in the course of reading the book?

I didn’t want to write a book that would let a Western audience off the hook, where a reader could sort of hover over stories about people of color doing bad things to each other in a third world country far away, and then cluck their tongue in judgment. That’s why I wanted to include stories about colonization, to hint at the origins of some of the things plaguing formerly colonized countries today. For example, the law in Malaysia that allows the government to detain people without trial is actually a legacy of British colonial days, when emergency laws were set up during the communist scare. This isn’t explicitly stated in the book, but I hope that the inclusion of colonial characters and Sarah (the white woman in the Silicon Alley story) shows Western readers how they are also part of this bigger story I’m trying to tell.

So to finally go back to your first question! It was a mix—some of the stories were already written (and had to be rewritten), while others were written specifically for the book after I decided on linked stories instead of a novel. I started the novel in 2011, so I guess it’s been seven years.

You blend the political and the personal so well—is this your natural way of seeing the world? And would you say that’s true of your characters, that their personal lives cannot be separated from the political affairs of their time?

I think I never had a choice to see personal and political as separate. In Malaysia, race-based politics and policies are a fact of everyday life. Then when I first moved to America, I was living in Chicago, and when I walked down the streets or waited for the El strangers would ask me “Where are you from?” or “Are you this or that?” I felt like a walking carnival game, where anyone could feel free to “play” me by guessing what I was. So I often saw my body, my actions, and my speech as more than just personal.

I think it’s the same for my characters. They are definitely caught in societal dynamics where many of their simplest acts have implications beyond the personal.

And wanting to be a writer, too, is of course a personal choice, but in a climate of censorship it becomes irrevocably bound up with the political.

You mention censorship, and that is woven into several of your stories, both officially (by the state) and unofficially (in not expressing oneself). Can you give us some background on censorship in Malaysia and why you’re particularly drawn to this issue?

I think it’s hard not to obsess over censorship when you want to write about what it feels like to grow up or live in a country, but then you also read about the government banning books, raiding bookstores, raiding artist homes to confiscate their materials, etc. Or living in America and reading about journalists covering the Water is Life movement being threatened with jail time. I remember reading a discussion about why the science fiction scene in Malaysia might not be as well-developed, and one of the comments directly called out government censorship as a reason people might not dare to envision a radically different world.

So all that becomes internalized. On a more personal side of things, my family is not terribly expressive in a verbal way. I think I grew up feeling like there were things that couldn’t be said, or best left unsaid, both inside and outside my home. So once I realized there were some topics that felt taboo to me, I decided it was holding me back as a writer, and I wanted to confront that self-censorship more.

Speaking of taboo topics, you have quite a few stories that deal with sex and sexuality. I particularly loved “Bright and Clear,” which starts off with a young woman and her mother driving, and the mother says, “So, you still a lesbian?” But then the story veers into a secret about her dead father. Which brings me to my next question.Your stories contain so many twists and turns, unexpected juxtapositions of situations. At times they feel almost impressionistic. Yet it also feels so organic. How do you approach writing? Do you start with a plot idea? Or do you write towards a theme, or a conclusion, or are you writing for the sound of language?

Thank you, I’m so glad you enjoyed the turns! I don’t really have a formula or uniform approach to writing, but if I think about it, many times I start writing because a particularly beautiful sentence comes to mind and I want to build a world around it. I guess that sort of makes sense because I got my start as a poet. So when I think of a line I particularly like, I’m going to try to use it no matter what, even if it doesn’t fit anything I’m currently writing—I’ll write something else around it, like the sentence is a seed and the rest is the meat of a fruit.

Do you think your command of multiple languages helps your writing?

Being trilingual does spark ideas for me. For example, the story you mentioned, “Bright and Clear” —the title is a literal and intentionally obtuse translation of “Ching Ming,” a day when people remember their ancestors and pay them respect, like what happens in the story. But the metaphors about getting lost and asking for directions are from a poem. A rough translation: “It’s drizzling on the day of remembrance, and passersby are full of sorrow as if their souls would break. When asked where an inn serving alcohol may be found, the shepherd points to the far distance, indicating Almond Flower Village.”

I’m not doing the poem justice, but basically it has wonderful sounds and beautiful sentences, but in another language. I took the feelings it evoked in me and wrote a totally different story in English, although I like to think some of what I felt from the original poem is in my story.

That makes a lot of sense. And it’s fascinating how words and phrases in one language can inspire writing in another. So now I return to Isabella Sin, the central character of several of the stories. She is taken as a political prisoner for allegedly writing a “sodomy poem,” which the Malaysian government finds inflammatory and pornographic. What was the inspiration for the character of Isa, and for this inciting incident?

There have been a couple of high-profile cases in recent years that stayed with me. One is Zunar, a cartoonist who draws what you might call political poems. He depicts financial scandals that the prime minister is involved in, for example. He was arrested for his art and some of his books confiscated, and now, years later, he’s still under a travel ban. He can’t leave the country to attend exhibitions of his own art.

There was also a dancer who was at an event where politicians were speaking, and she dropped yellow balloons around the venue. There were words printed on the balloons—I forgot the exact words, but they were something like “Justice” or “Fair elections” maybe. And she was arrested.

So the character of Isabella was definitely inspired by real life, but she was also borne out of something I thought about a lot, which is: How does a person who feels alienated in their own country, who perhaps does not feel loved by this country—how do they develop a sense of belonging or even patriotism? How do minorities or stigmatized groups find a sense of belonging?

I liked how you addressed this question of patriotism in “A Malaysian Man in Mayor Bloomberg’s Silicon Alley,” which again, follows unexpected twists and turns, this time of Howie Ho, who returns from the United States to vote in the Malaysian election, and then finds himself proposing to a young Malaysian woman—only to be spurned. As an immigrant yourself, how do you view the concept of “home” and how does this play out in your work?

I’ve been told to “go back where you came from” in both Malaysia and America. So for a while I couldn’t help but think of “home” as a place that doesn’t exist, but that other people really want me to go to.

So that’s the negative interpretation. A more positive interpretation is —especially now that I’m older—I think of “home” as whether you can create the right conditions in which to connect with your loved ones. It’s an abstract interpretation, but I think it comes from the void I was talking about—I’ve had practice thinking about “home” as an abstract thing. So it doesn’t matter where I am. “Home” is —can I create the right conditions that let me have meaningful relationships?

I like that interpretation. I think we all feel, to some degree, that home is a sense of belonging, no matter what the physical place. If you had to pick one story as your favorite, which would it be and why?

This is probably not a great reason, but we all have our failings, so… heh. I’d pick “Taiping,” because years and years ago, when I hadn’t published much, I came across a story with that same title in a year’s best anthology. Taiping is where I was born and raised. Not so for the other writer. I remember reading that story, which was stamped with a mark of excellence, and feeling something like dissatisfaction. I wanted a story named “Taiping” to be written by me, or someone like me. So now I’ve written one.

You’re originally a poet, but you’re also a software engineer by day. Do these other sides of you influence you as a writer in any kind of tangible way? And would you quit your day job if you could?

I’ve come to enjoy my work as a software engineer and derive some satisfaction in being part of a growing group of women in a male-dominated industry. A lot of people have this idea that engineers just sit and write code in isolation. But if you work for a company, that isn’t true at all. Really it’s more like Andy Warhol’s factory, where there is a unified vision of what an end product should look like, and many pairs of hands chipping in to work towards that end result. It’s a lot of anticipating what others will say about the portion of code you’re working on, and so when I’m writing code I have to always keep in mind my peers’ response. Writing a book isn’t like that at first, but later on, when you work with agents and editors, that aspect does come more into play. I think the perfect balance is write your own truth, while remembering that you are in conversation with other writers.

Honestly, having a day job is also humbling in a good way. I care so much about my writing, and when I go to work it’s very apparent how no one is waiting for me to finish a book or even a short story, whereas if I miss a deadline at work people do care. It helps me interrogate myself again and again: Why am I writing? Why am I spending all these long years on something no one is waiting for? I think the constant reminders are healthy in a perverse way.

What words or phrases would your dream rave review contain?

Ooh such a tough one! Okay, not to reveal the chip on my shoulder, but I think a dream review for me would be focused on the use of language in my book. I’m not a native English speaker, and I don’t have an MFA, but I spend time thinking about language and sentences, and I hope some readers notice and take something away from my work from that aspect.

Well, I, for one, certainly took note of your sentences and paragraphs, which are both elegant and unique. Do you think you’ll continue to write about Malaysia for your next book? Could you ever envision yourself writing something completely different, in terms of themes, characters, or sensibility?

Thanks, Mira! And yes and no. I think what I write will often be from the lens of being Malaysian. But the book I’m working on now is set mostly in the United States—I think I have things to say about living in the U.S. too. As for writing something completely different, it’s my hope that one day I will be able to translate Malaysian books written in other languages into English. It’s an intriguing challenge.

From Though I Get Home

Hunger pinned her to the bunk. Starvation impaled her through the stomach, keeping her down on the thin mattress, resisting the momentum of her feebly raised head. Her neck strained to bring her vision to the requisite level such that she could observe the movement of sun against her prison walls. The sun was her way of telling time and estimating the next delivery of food.

Hunger pinned her to the bunk. Starvation impaled her through the stomach, keeping her down on the thin mattress, resisting the momentum of her feebly raised head. Her neck strained to bring her vision to the requisite level such that she could observe the movement of sun against her prison walls. The sun was her way of telling time and estimating the next delivery of food.

Not that it mattered now. It was the third week into her detention without trial. She did feel secure, as if nothing would ever happen to her again, until death. The days lost their shape, shedding the definition of hours and minutes. Her body, too, lost its shape, pooling downward, lowering her center of gravity, rooting her toward dirt and dust.

They said she was staging a hunger strike. Isa, on her part, felt that the refusal of food was really to make life behind bars more interesting. The meals they brought to her cell were markers of time, and she had looked forward to the packets of rice and gravy as daily celebrations. But then she’d started feeling like a Pavlovian dog. The nods of the men who handed her sustenance became sinister, laced with degradation. She resented the regular reminders of her weakness and dependency.

After minutes of work, she managed to prop herself up on one elbow. A rolling wave of dizziness lurched her, listing, tipping. She smiled widely. In her teenage years, when she’d lived a sheltered life, she had tried many times, each attempt lasting days or weeks or months, to go on a diet. It didn’t much matter what kind of diets they were, or how much science was behind them. The hope was what she needed. She wished, on the other side of each experiment, to find a slim, beautiful her, standing still with folded hands, waiting.

And now, locked away, she would finally obtain the thinnest body of her life. She dreamed, still smiling, of her wafer physique gliding effortlessly among obstacles thrown up by invisible enemies. Anything anybody erected against her she slipped past with a slight sideways turn of her frame, her arms extended ramrod above her head, as if surrendering, but really evading, winning.

She came to. And was disappointed to feel that she was again flat on her back, her previous progress negated. Shadows swam before her eyes. She opened them. Men. Men were leaning over her, explaining something, but not to her. To each other, or maybe to an unseen observer. She sighed. Rank air filled her nose. Rolling her eyes upward, she caught the glance of one man, who started talking faster.

Hands pressed down on her shoulders, pinning them. A hand touched her lips. Isa suddenly wondered what clothes she was wearing. Whether she wore any.

Another pair of hands caught hold of her ankles. Her mind, wandering, entertained the absurd vision of a single many-limbed being. It had paused its speech when it extended hands and fists to restrain her, but now it started up again. Isa thought it might be expecting a response from her, but she could not understand it. When she opened her mouth to tell it so, fingers slipped through and stretched her lips. She gagged and mush rushed in, filling her.

Of course she tried to spit. Of course she thrashed. At first. Then the mush began to acquire flavor and become more than texture. It tasted first like somebody else’s vomit, and then like her own. And then it became her, and she was being force-fed herself.

She reclosed her eyes. Up floated a piece of advice from her dead father, given a lifetime ago. What to do when overpowered by a criminal, such as a robber or a rapist: Do not fight. Survival should be your only focus. Everything other than your continued breathing—be it jewelry, money, body, honor—is expendable. Save your life. Do not fight.

Oatmeal. That was what they were forcing into her mouth.