Red Guard founder Alex Hing talks 1960s radicalism, sympathizing with North Korea and that infamous punch.

October 9, 2014

[Editor’s note: This interview is part of The Counterculturalists, a project of the Asian American Writers Workshop that looks at Asian American and ethnic identity as an alternative, rebellious, uncategorizable subculture, an avant-garde in both politics and aesthetics. Through interviews, original essays, multimedia, and criticism, we’re featuring writers and artists whose work collectively creates a countercultural space.]

Alex Hing’s pithy, aggressively macho lines, a common mode of expression for activists of the 1960s and 1970s, made him a loudmouth to be reckoned with. Exhibit #1: “We are Asians, and as such, identify ourselves with the baddest motherfuckers alive.”

A former street tough and martial arts master, Hing helped found the Red Guards in 1969. The Bay Area Asian American revolutionary organization was modeled on the Black Panthers, and was one of a panoply of radical groups in the left wing of the nascent Asian American movement.

For 40 years, Hing’s reputation has preceded him, and unlike some of his contemporaries from the 60s, who’ve gone on to become professors, lawyers, elected officials, or financiers, he’s remained part of the working class, as a hotel chef in New York City and an active member of his union, Unite-Here Local 6. So I wasn’t quite sure what to expect when I met him recently in Soho.

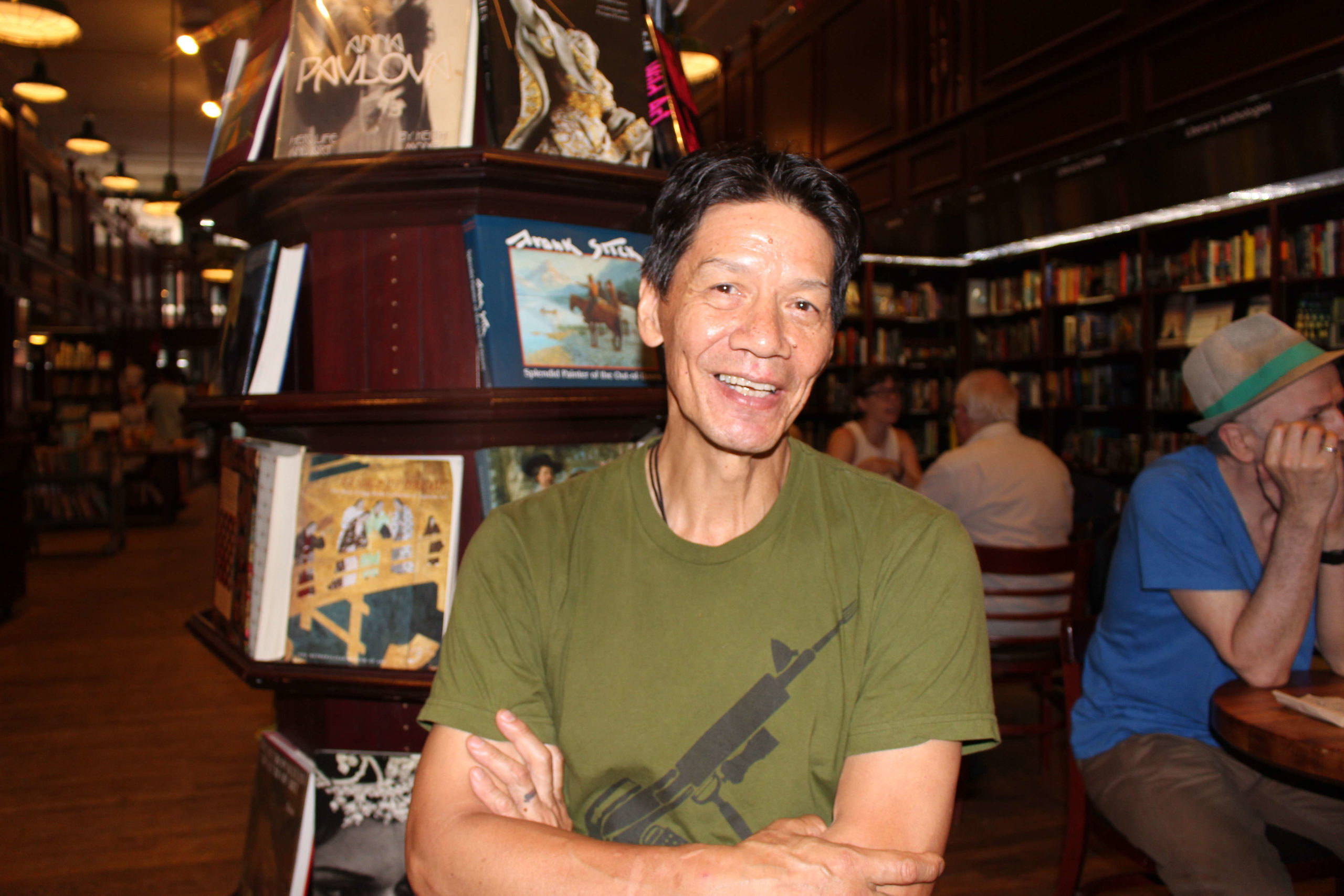

The man who sat down across from me at the Housing Works Bookstore café was friendly and mild-mannered, and talked enthusiastically about how he and his wife had scored an apartment in Harlem with a private roof garden and “a gym that looks like an Equinox.” But, he wanted me to know, “I’m still doing stuff, and I’m still counterculture.”

The Red Guards only existed for two years, but the organization became quickly known for your brash, confrontational style and revolutionary politics, not to mention the berets and armbands.

We did a lot of crazy things. I was really young, and you know, we were revolutionaries. We had a lot of fun. It was dangerous.

I’m curious about the strong connection you had to the Panthers. You even had your own Ten-Point Program.

We were affected, everyone in our generation, with a yearning to breathe free, to break away from this stultifying society. A group in Leways [a Chinatown youth pool hall and non-profit agency] formed because we couldn’t get jobs, and we were targets of police. These are my friends, I grew up with them.

A handful of us were closely following the Black Panther Party. They were arming themselves, and they were talking politics. At the time, we felt an extreme urgency because police were killing people, putting us in jail. My cousin was handcuffed and beaten to death in prison. People think this doesn’t happen to Chinese people, nah. This was why armed self-defense wasn’t just rhetoric, some macho thing we thought was cool. This is what we were facing.

We decided we needed to be a conscious core of revolutionaries. And then we made contact with the Panthers.

…we felt an extreme urgency because police were killing people, putting us in jail.

You were born in San Francisco and spent your formative years there, and your parents owned a nightclub.

We grew up in a building where almost every unit was performing artists. Singers, dancers, you name it, people selling Chinese opera music. This was in Chinatown. My mother she told me that in junior high school, she signed us all up for the orchestra. She said she did this because she wanted us to understand that every time we hear music, somebody has to work to make it.

My father was a magician. So it was counterculture from the jump.

And it was the height of the counterculture at the time.

San Francisco was the heartbeat. And I was involved in the Haight Ashbury at the time, I was at City College. All these people descended on the Haight Ashbury without a clue what to do. A lot of them were racists, a lot of them were there just to get laid and get high.

And even though we didn’t like these people coming, they need to be taken care of. So groups like the Diggers started doing that, set up a bread factory, gave away bread. The Haight Ashbury free medical clinic came about.

And there was a view at that time, that we could have a society that was not based on money. That everyone could be free. And I still believe that.

I’ve never really had money, I’m very bad at finances, well, I’m not that bad—I’m Chinese—but I don’t pay attention to it. And strangely enough, this has all worked out.

What were the reasons you became an activist?

Getting arrested was a big one.

What happened?

Because my parents worked in nightclubs, my older brother was in charge of taking care of us. But he couldn’t do that, so I fell in with the kai doi [Cantonese for “bad boys”]. Pretty much, just having a lot of fun, stealing cars, we did some crazy things. And got busted. When I was in jail, I started reading and I became convinced there has to be another way.

You got involved in the civil rights movement.

There was the armed struggle going on. People were being killed for no reason, black schoolgirls were being murdered in a church, people were being murdered for registering people to vote. You can’t have a sense of justice and not want to be involved in that movement to correct that. You just can’t.

The civil rights movement was where I got my ABCs in organizing. The first time I knocked on doors, trying to win people over to our position, to get them to vote, to go to meetings and all that stuff.

How did you go from voting rights and door-knocking to then forming the Red Guards?

I lived in the Fillmore, the black district in San Francisco. I was walking home one day, and this cat stopped me. I had all these buttons on, and he said, “Hey man, what’re you going to do this summer?” I had a job as a dishwasher that summer. And I said, “I don’t know, I was maybe thinking of going to Chicago, for the DNC.” And he says, “Well, I got something better for you.”

He said, “There’s a bus leaving this weekend that’s going across the American South, to carry on the legacy of MLK.” And I said, “Well, I’m more of a Malcolm guy.” And he said, “This campaign, the Poor People’s Campaign, is being kicked off by the Black Panther Party at the Oakland auditorium. And what we’re calling it is the last chance poor and oppressed people to engage in nonviolent political activity.”

The unsaid thing was that if it failed, then it’s armed revolution. So I got on this bus and there were all these crazy Chicanos, and white liberals, and we’re in this caravan going across the country, stopping at two to three churches a day, having rallies. The Klan put bombs on our buses when we stopped in Kentucky, Louisville, and then we were in Washington, DC.

Forty years before Occupy Wall Street we occupied the National Mall. There was like 6,000 of us, and we demonstrated every day. And you know, the National Guard, the police, just bulldozed the place flat.

And that’s when I said, Asian Americans need to be a part of this.

Why did you feel that? Because at the time, numerically speaking, we’re talking about very small communities. In 1970, Asian Americans made up less than one percent of the total US population.

Yeah, but when you grow up in a community you don’t look at it as large or small, it’s just what it is. Our people, my friends, comrades, brothers and sisters were all facing the same thing that other people were facing. The same kinds of situations due to capitalism, US imperialism, as it applies to minorities. We didn’t have equality, and the only way that we can get equality is by making revolution. So that’s how [laughs].

I dropped him with one punch but our chairman went up and… crush[ed] his eyeglasses. I think that was worse…

Were there moments you think you went too far?

I got invited once to speak at an anti-war rally because we were part of this Asian movement against the Vietnam War. And as I was going to speak, I think it was David Hilliard, [chief of staff of the Black Panthers] said something like, don’t forget to mention the guns.

What David wanted to do was to raise the issue of armed self-defense, and we were kind of like cadre of the Panthers, but it was inappropriate.

I was booed off stage, pretty much. That was one moment where I learned, don’t ever do something that someone tells you to do, no matter who they are.

You also got into some very public fights with people.

Oh, you mean when I hit Frank Chin?

He called the Red Guards “yellow minstrels.”

I would do it again.

I don’t know what Frank was advocating. Now if you have your own hangups because you didn’t grow up in the community and you’re finding your roots, you don’t do that by making fun of people who are downtrodden, and you don’t come into our community and our office and talk shit like that. And think that you’re just going to walk away.

He just strolled into your office in Chinatown?

He was invited to speak at the Youth for Services offices in the Kearny Street Workshop. A lot of the social service organizations had offices there. So here comes this guy and we know what he’s been saying. It’s been in the press. And… it wasn’t much. It was like one punch. [pause] I dropped him with one punch but our chairman went up and what he did was crush his eyeglasses. I think that was worse than the punch.

I would tend to agree with you. It’s kind of important to be able to see.

Especially if you’re a writer. But I don’t regret that at all.

His critique was that a lot of Asian Americans, especially the Red Guards, were performing blackness.

As you pointed out, we were a very small minority, but our situation was not that different than African Americans. Particularly if you hung out with the Panthers, people are wearing sunglasses at night and smoking cigarettes and listening to jazz, and it was like, it could’ve been in the Fillmore, or west Oakland. So culturally we were not that different than the blacks. And when you’re really young and you want to engage in social change, you need role models. And here are the Panthers. They’re calling themselves the vanguard of the revolution and at that point, they were. They were out there engaged in armed struggle with the cops for no reason other than they refused to let the police kill their youth.

They would say, “We’re going to stop this. We’re going to fight back. And we want land, we want housing, we want education, we want all this stuff” that we wanted too. They were our role models, and the Panthers introduced us to revolutionary struggles going on in Asia.

The route to Maoism was actually through the Panthers. And not stemming from cultural or ethnic nationalism.

Because our community was so anti-Communist, and the KMT [the Chinese Nationalist Party] completely controlled Chinatown, we could not really examine that. The Panthers weren’t just looking. It’s actually getting into what Mao was saying and applying that to our situation.

…[it] was a life and death struggle. But on the other hand… we did a lot of psychedelics.

You’ve described a lot of what the Red Guards did as political theater.

When we gravitated to Marxism-Leninism, everything became about that. You have a correct line, and everything that’s not the correct line is bad. So was it political theater, yes and no. We were deadly serious about the situation, which is that there was a war going on, the United States was committing genocide both at home and abroad, and the Asian community was just beginning to get enough numbers to begin to have impact.

So that part was a life and death struggle. But on the other hand, we did have a lot of fun. You know, we did a lot of psychedelics.

What about the critique a lot of women had at the time, that the Red Guards were patriarchal?

All those criticisms are correct, but you have to take them in the development of history. The women’s movement was just beginning. We were aware that women hold up half the sky, but within our own organization, was there women leadership? No. And it took a lot of struggle and not all of us accommodated it. There were things that I said and things I did that I’m not proud of. But I don’t think there’s anybody who starts out with a pristine agenda.

We made a lot of mistakes. But we raised revolutionary consciousness. We built the anti-war movement among Asian Americans on the west coast. And we were up front uniting with the Third World Liberation Front at the SF strike. You wouldn’t have ethnic studies today without that.

There’s been a tendency in Asian American history to pretend we didn’t even happen. What you have today is demographics playing itself out. “We have more AAs so we have more power.” But we were active before immigration was really opened up. And we were calling for an ethnic identity and political power before we had numbers.

And because of that, we advocated uniting with African Americans because our fight is the same as theirs. And I still think that’s the case.

In 1970, you went on a delegation to North Korea and North Vietnam and then China.

China, North Korea, and North Vietnam were all socialist, liberated countries. They were trying to make socialism work. I could go on about why that’s not a model any longer. But it was fascinating that there were people that liberated themselves from U.S. imperialism, and Vietnam was in the process of doing that at great cost. That was a life changing experience.

One thing that most people don’t have a clue about is North Korea. Who talks about North Korea, who supports the Kims? I do. And why? Because they were engaged in the war in 1953 when there was no anti-war movement hold back the unbridled wrath of U.S. imperialism.

And when we visited that country, and we saw evidence of what this monster had done to innocent people, just everybody. If you were Korean, you died. Your family died. Your crops died. Your house gets stolen. Your livestock gets killed. You get thrown in rivers, alive. You get poisoned. You get tortured.

But you had fought U.S. imperialism to a standstill. This is the biggest most powerful country on earth, a nuclear-armed country.

When we were there, the majority of the people were children.

…when you call someone crazy, that means you can never negotiate with them.

Because their parents—

Were dead. They had to repopulate and they had to raise kids. So, in order to do that, when you’re pretty much isolated, people starve. But from their perspective, people are making sacrifices for the struggle. So, what is not helpful is to call the leaders crazy. Because when you call someone crazy, that means you can never negotiate with them. There’s no rationale behind what they’re doing. You can’t reach an understanding with a crazy person. The thing about it is —the hypocrisy. If you’re talking about North Korea not having nukes, get rid of yours first.

In the ’80s and ’90s, the Left receded. You became a union activist.

I started out as a dishwasher, and that’s kind of how I landed. I believe in the work. I don’t see any need to go anywhere else. I dropped out of school. I don’t see the need to go back. I just landed in the right union. I like working. I like being a cook. And in order for me to continue that kind of existence, I have to be a union activist. I have to represent the union in my place, and organize people, for power.

Is that when you got married and had your two kids?

No, it was more like when I got divorced. And it was good in the sense that it was a way to take a break and figure out what I should be doing. I would go to anti-war demonstrations by myself.

Did you miss that feeling of community?

I really do. I wish we had never fallen apart. For instance our organization [the League of Revolutionary Struggle] had a child care system where you could drop your child off.

During that time there was a very high-level commitment. It wasn’t sustainable. I don’t think people are willing to do that now.

Do you feel Occupy Wall Street is the sort of movement we need now?

I thought it was wonderful. I think people should organize however they can to do whatever they can.

So I’m getting older, and we used to say “revolution in our lifetime.” I have to live a lot longer, a lot, lot longer for that. So I think what is needed is that people come together around common interests and do whatever they can.

Whatever you can do, wherever you are.

Do something. If you can write, write. If you can dance, dance. Like I’m a martial artist, I teach tai chi. I’m a cook, I cook. You have the ability to make change, even if it’s just one person at one level, one really small thing, you can do it.

One thing that you briefly alluded to is your disenchantment with Marxism-Leninism.

Deep down inside, I’m still a Marxist. And Marx says that in order to have a revolution — a transcendental revolution — a fundamental change in the means of production, it has to be a technological breakthrough.

And so even though we upheld these ideals of what we wanted a society to look like in the future, there was no material basis for that.

That’s completely changed now with the Internet in the digital era. There is a technological breakthrough that can become the basis for a new method of perfection that could eliminate a classed society.

Some would argue that the new information based economy has only widened divisions–of income and employment inequality, even access to information.

People have free access to information. That’s empowering. Plus you know how to use the Internet. You could use it as a revolutionary weapon.

To me, that’s the least of it. I’m in a different place now because I think all politics is subordinate to rapid climate change. So you gotta be pretty out of it if you’re progressive and revolutionary to just ignore that and keep going.

This is the future we’re looking at. So that’s where I’m kinda turning my head now. Here’s the thing about technology. Even though we’re faced with this irreversible rapid climate change, we have the means, technologically, to abate it. The means to make a new society.

Have you read Grace Lee Boggs? She’s talking about the same kinda thing, but in a different way. She’s saying that in order for the next American revolution to happen, there has to be a spiritual transformation. There has to be a change.

A revolution in our values.

And people’s perspectives of themselves vis a vis the cosmos. Right? So, I think right now, if you do that, you’re counterculture.