India Home offers South Asian seniors a place to be themselves

September 9, 2021

Three days a week, Usha Mehta makes sure to get up while her husband is still asleep. She begins the rituals that have seen her through sanity over the course of the last year and a half: brushes her teeth, changes into a jogging suit, and lays out her yoga mat in the living room. Then she slowly turns on her iPad and logs into Zoom yoga. As Mehta’s screen tessellates with those of the other participants, the group of 50 or so South Asian seniors stretches and laughs together, using the minutes before class begins to greet each other with “Good morning(s)” and “Jai Shri Krishna(s)”.

Some tune in from their own living rooms or kitchens; others have screens positioned so closely to their bodies that it is impossible to tell where they are–only that they, too, are swiveling their hips and slowing their breathing. One budding yogi, in the middle of an important call, snuggles her cell phone between shoulder and cheek as she jogs in place. A television’s edge can be seen in another participant’s background, and her husband pops in during breaks from the cricket match onscreen. Mehta can settle into the reassurance that her community is–against all odds–weathering the storms of the pandemic, isolation, and aging far from home.

Mehta was not a regular yoga practitioner before the spring of 2020. But for the last year and a half, she has rarely missed a Zoom yoga class held by India Home, a nonprofit in Queens that focuses on the needs of South Asian seniors.

The chance to start her day with friendly faces has been impossible to pass up during the pandemic’s long stretch of isolated months. Mehta lives near Elmhurst Hospital, and when the pandemic began, her daughter begged the sociable 76-year-old not to leave her home. The early days were particularly hard. Stuck inside, unable to concentrate enough to read or watch television, Mehta was safe, but bored, and terribly lonely. “If India Home didn’t do yoga classes or anything like that,” she said, “I don’t know where I would be.”

Zoom yoga has been one of India Home’s most popular pandemic offerings. The class gives seniors a chance to move and connect with their bodies, but it also allows them to begin the day connecting with one another. ”When you want to go on the zoom at 9 am, you have to start at 8 thinking ‘OK, I have to start, I have to do this,’” said Jyoti Mandavia, who is 70 and joined India Home soon after she retired in 2018. “Otherwise, during the pandemic, I couldn’t go out–I would just lay down, and my daughter would call and say ‘Mom what are you doing?’ And I would say ‘What can I do, the news is saying everyone is dying.”

Morning yoga has given Mandavia a sense of routine and ballast. Even after she logs out of the class, the warmth of its contact stays with her, like sunlight cast on skin.

Mehta and Mandavia both immigrated to the U.S. from East Africa in the 80s and live a walk away from the India Home center in Sunnyside, Queens. India Home was established in 2007 with the mission of providing culturally competent elder care to South Asian and Indo-Caribbean seniors in the borough. That care takes different forms: vegetarian and halal meals, cheerful translation services, a range of activities from bhangra dancing and Bollywood screenings to lectures about acupuncture and nutrition. For more than a decade, Desi seniors have been coming to India Home to touch the fabric of a culture they never truly folded away.

The organization sets seniors up with benefits; it walks them through the intricacies of healthcare bureaucracy. And through its empathetic staff and emphasis on cultural touchstones, it has created a community for a population in need of connection. When the pandemic hit, India Home quickly pivoted to deliver fully cooked meals and pantry staples and created a wide range of Zoom programming. (Since June, India Home has begun to open up its centers at 25 percent capacity.)

“India Home is keeping me alive,” Mehta said. “If India Home wasn’t there, I would have gone into a depression and ended up in a hospital.” For both Mehta and Mandavia, what was a fun once-a-week outing prior to last spring has turned into a lifeline.

□ □ □ □ □

Long before the pandemic, Dr. Vasundhara Kalasapudi, India Home’s founder, had worried about the kind of care that elderly South Asians had on offer in New York City. When her father was diagnosed with vascular dementia 17 years ago, she started calling local agencies to see what options were available if he came from India to live with her in Queens. It quickly became clear that her father’s quality of life would suffer. Despite the borough’s sizable South Asian demographic, Dr. Kalasapudi was told over and over that there were no facilities that would be a good cultural fit or even reliably serve vegetarian food.

“That’s when I decided it will be a punishment if I bring him here,” Dr. Kalasapudi said. She had wanted her father to stay in America. She worried that otherwise his dementia would cause him to forget her. But her sister and brother-in-law in India took on caregiving responsibilities instead, and Dr. Kalasapudi had to satisfy herself with a daily long-distance phone call.

Asian seniors are New York City’s fastest-growing senior demographic, and Queens is home to nearly half the city’s Asian population. Dr. Kalasapudi realized that the issue she had uncovered was not a niche one; it had affected or would affect hundreds of families in the borough. Knowing that real estate would be the nascent group’s biggest hurdle, she decided to establish programs within established senior and community centers like Services Now for Adult Persons (SNAP). In exchange for space within such centers, India Home offered to hold weekly events for South Asian seniors, cater food from local South Asian restaurants, and hire staff fluent in the necessary customs and languages.

Seniors who come to India Home speak a small constellation of languages: Bengali, Hindi, Gujarati, Urdu, Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam. But manners are just as important as mother tongue. In other centers, Dr. Kalasapudi explained, “They call people with the first name: ‘Hey Martha, come here.’ Even if that lady is 70 years old! Whereas in our culture, we would never dare say to some 70-year-old lady, ‘Hey Rama, come over here.’ We’d say ‘Hi Rama-ji.’ That’s a huge difference.”

In early 2009, India Home began a program in the Sunnyside Community Center. The chapter there mainly serves Indian immigrants who came to America in the 80s and 90s. India Home expanded three years later inside the Queens Community Center in Kew Gardens, where it serves a more mixed community; most attendees speak English, and meals are a little less spicy to accommodate the white seniors who often drop in. Both centers had once-a-week programs that routinely drew 50 to 60 attendees.

In 2014, thanks in large part to a grant from the local City Council, India Home opened the Desi Senior Center in Jamaica. It was conceived specifically for the Bangladeshi Muslim population, which the Asian American Federation has reported to be the fastest growing senior group in New York City. In pre-COVID times, more than 100 seniors gathered in the basement of a Jamaica mosque three times a week for halal meals, physical exercise classes, and the chance to gossip over the pages of Bengali newspapers. The opening of a fourth center primarily for the Indo-Caribbean and Sikh communities in Ozone Park was put on hold last March and just opened this summer.

□ □ □ □ □

Whether their arrival in America dates back months or decades, the seniors who seek out India Home are all searching for a community that can remind them of what they have known. There is a pointillism to culturally competent care: small details (the phrasing of a name, the spices in a dish, the verses of a prayer), when daubed together, create the impression of belonging and reclamation. The seniors are given the space to remember what it was like when they were young, in a different time on a different shore.

Even for those who have lived and worked in America, and have ostensibly assimilated, there is an unmistakable desire for the formative. “After a certain age, people are looking for that comfort where they can talk to someone in their own language or eat the same food, share the same recipes,” said Kavita Shah, India Home’s Creative Aging Director. “You don’t want to try hard to fit in. You want to feel that you are fine, that you are in your comfort zone. Here, the seniors can be themselves.”

Seniors are grateful that they can eat daal and rice, and pen their creative writing assignments in Bengali. Cultural touchstones like food and language are “reminders of who you are and where you came from,” said Howard Shih, the Asian American Federation’s Research and Policy Director. “That’s important in keeping people from feeling like they are losing their sense of who they are.”

Some of the seniors are trying to discover who they are now, outside of jobs they have given up and children who have moved away. “I’ve had people call in who just retired and found out about us and said ‘All our life we’ve been busy working and we never thought of making friends,” Shah said. Now that they are older, they tell her, “We want to connect with our people.’”

In a way, the staff of India Home is preparing for its own future. “One of our board members, she used to say this is all getting ready for our old age,” Dr. Kalasapudi said. “We’ll need these services! It’s not just about food alone, it’s about language, culture, togetherness. Some of the seniors live in very rich homes with very rich families, but they’re dying to come to the center just to spend time with their age group.”

Usha Mehta’s daughter Harshna, a physician in New Jersey, has seen her friends’ parents suffer in similar situations. “In Asian culture, the parents give everything to their families,” she said. “They don’t necessarily develop social ties throughout their life, because their social ties are typically centered around their children.” Now, Harshna said, her mother’s social life seems busier than her own.

In January 2020, she collaborated with her mother’s friends at India Home to throw Mehta a surprise 75th birthday party. Kavita Shah distracted Mehta by whisking her along for errands while other seniors helped bring in the catering, set up banners and balloons, and snuck in her grandchildren.

“In my life I’ve never celebrated my birthday that way,” Mehta said. “Back home, when I was young, there weren’t parties or a big craze. When I grew up I never had those parties like sweet 16, or 18th, and I was missing that. I was so happy everybody was around. You see that people love you–that’s a great thing.”

Harshna recalled how, at the end of her mother’s birthday party, Mehta’s friends had come up to her to chat about how much her mother loved to dance, about the play she had recently been in, about a host of talents she had never known her mother had. “She gets to dance now, which is amazing,” Harshna said. “She’ll have dance shows and send us videos. She’s so proud of them, and we’re so proud of her.”

Bharat Shah and his wife Usha immigrated to the U.S. two decades ago and started coming to the Sunnyside center soon after it opened. He said that the organization has transformed his life. Before being introduced to the center’s classes, Shah had never sung, never danced, never taken a painting or yoga class. “Here, after joining India Home,” he said, “I changed completely.”

□ □ □ □ □

Though united under a South Asian umbrella, the India Home centers serve populations with divergent needs. The Desi Senior Center, conscious of the needs of its particular demographic, has little overlap with India Home’s other branches. “Our seniors are conservative Muslims,” explained Nargis Ahmed, the center’s director. “In other senior centers they do painting, dancing, American games like bingo. Our seniors don’t feel good about going to those senior centers. It’s a totally different kind of culture.”

Part of its value is simply providing seniors a place to come and be themselves. Away from their families, “they breathe a fresh breath,” Ahmed said. At home with children and in-laws, the seniors feel a sense of reserve. “They say when they come, they feel like it’s their own area,” Ahmed explained. “They are free to talk.” Though the center would only open its doors at 9 am, and asked seniors not to arrive beforehand, they would routinely come as much as a half hour early. “Even in the cold, they would come,” Ahmed said. “The caretaker would be very upset.’”

All of the meals and programming India Home provides are free, though seniors are encouraged to give a donation of a dollar or two for meals. In Sunnyside, a member will occasionally cover the day’s meal for everyone at the center to celebrate a wedding anniversary or the birth of a grandchild. At the Desi Senior Center, however, “more than fifty percent can’t give in that sense,” Dr. Kalasapudi said. “Some of them, the only good meal they get is when they come to the center. Their needs are totally different. They need help with food stamps, social security, transportation.”

Ahmed estimated that in the other India Home centers, 97 percent of seniors had experience living or working in America. “But in our center, ninety-seven percent just came here because of their children,” she said. “Our seniors, they don’t know the language. Whenever they go to the hospital, the bank, or a citizenship interview, they need someone to assist them.”

The Asian American Federation found that recent senior Asian immigrants are less likely to receive federal benefits than longer-term residents; the majority of the Desi Senior Center attendees immigrated to America within the last decade. It’s a large part of the reason that India Home began offering case management services in 2015, helping connect seniors with health insurance and secure SNAP or housing benefits.

South Asians are often perceived to be wealthy, an assumption that papers over the lived reality of a wide demographic. Bangladeshi seniors have some of the highest poverty rates in the city. When India Home released its own survey in 2019 of nearly 700 South Asian seniors in New York City, it found that 70 percent of respondents reported having no personal income and 63 percent relied on their children for financial support. Ninety percent of the respondents with an active personal income made less than $20,000, and less than half of the respondents had access to Social Security or other government benefits.

In a 2016 AAF survey, more than 50 percent of seniors expressed having symptoms of loneliness or depression. “If you look at the statistics, Asian seniors have one of the highest poverty rates,” Shih said. But he noted that the challenges they face are the same as seniors of any other racial demographic: housing costs, being able to put food on the table, social isolation.

Seniors walk into the case management office in Jamaica carrying bags of long-accumulated mail, unable to tell if anything in the fat sheafs of letters might be important. It’s almost always junk mail, said Selvia Sikder, India Home’s former Program Director. But when she tried to point out that the missives are disposable if confounding clutter, the seniors would get confused, telling her that the letters were clearly addressed to them.

It’s why, at the Desi Senior Center in particular, the focus is not just on ameliorating loneliness or staving off boredom. Difficulty acclimating doesn’t just mean a loss of community. Deciphering a letter or making a call to a benefits hotline can feel impossibly overwhelming.

Even those who live with their families can find themselves in the dark. “Some of the seniors, they feel their family doesn’t have the time for them,” Sikder said. “If one person is working a night shift and then in the morning they have to drop off kids and then sleep and then go back to work…” she sighed.

These adult children are the so-called “sandwich generation,” named because they are caught between the needs of both aging parents and growing children. “You would think that in a multi-generational family setting, there would be no social isolation, but that’s not necessarily the case,” said Shih. “Grandchildren are in school, adult children working two-to-three jobs. If seniors don’t know how to navigate public transit, they’re stuck at home.”

Ahmed has also occasionally seen children bring elderly parents over in order to take advantage of government assistance. “These families, they cannot even survive themselves but are bringing their parents. Sometimes, if they are really low income, they get food stamps on top of social security and home care,” she said. “These people are suffering here, they want to go back.”

But other families will bring parents over even if there is no promise of support, out of the intertwined sense of love and duty that haunts intergenerational ties. Ahmed’s in-laws and her father have all lived with her at various points. She wishes the Desi Senior Center had existed during those periods. “They didn’t have anything,” she said of her relatives. “They were home all day long.” Her in-laws, at least, had each other for company when no one else was home. But Ahmed still feels for her father’s sense of isolation.

“He was really striving to have a friend with whom he can talk,” she said. “With us, how long can he talk? You can gossip with friends, not children. It was very, very hard for him to pass the days along by himself at home. I don’t even know–at that time life was so busy–maybe we didn’t even ask him what he did all day long.”

Ahmed remembers how she would prepare food for her father each day and leave it inside the fridge on a plate. Looking back, it hurts her to think about how difficult it must have been for him to eat by himself. At home in Bangladesh, he would have been surrounded by family at every meal. “But here he was, warming up his food by himself. It was very painful for him.” Whenever she recalls that time, she said, “I think ‘if only Allah would only give me those days back again.’” Instead, she focuses on the days of the seniors now in her care.

□ □ □ □ □

When the pandemic arrived, the organization’s three centers had to close their doors and pivot, quickly, to find new ways to care for a vulnerable and isolated population. At first, India Home provided meals that seniors could pick up at the centers. But the staff soon realized that only a quarter of the regular attendees were coming to get them. So the organization began a grocery and meal delivery service five days a week for more than one hundred people. Originally intended for seniors in Queens, it was soon expanded to other boroughs.

But people cannot live on rotis alone, and by early summer, India Home had translated all the programming it could to Zoom. “That was a difficult time for our staff,” Sikder recalled. “The majority of our seniors don’t speak the language, aren’t tech savvy, and don’t have smartphones or computers.”

Ahmed wasn’t sure the Desi Senior Center’s seniors would even be able to log in. “It was new for us, but we really took a lot of hassle to teach them over the phone,” she said. “We would talk to their children and say please help your parents get connected.” Staff members from all the centers made phone calls with seniors, painstakingly training them one-on-one about how to use the app. Home-delivered meals were accompanied by flyers about how to download zoom on a smartphone.

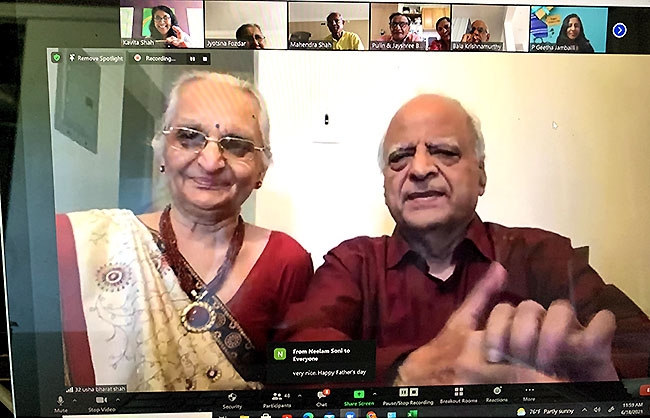

And while the pandemic initially upended the organization’s structure, it has also enabled them to expand their reach and their programming. Because access to the classes is no longer restricted by geography, seniors tune in from California and Canada, eager to experience what they have heard about from their friends and relatives. Instead of having a designated day once a week to come to the center and partake of its offerings, seniors can tune in every day for ESL classes, technology classes, health talks, and “creative aging programs.” Kavita Shah said that they are planning to continue the virtual sessions even after the pandemic ends, since it enables them to reach seniors who may live in Queens but still have difficulty coming to a center.

Usha Mehta is grateful for all of the Zoom programming, but she has been most touched by the personal attention India Home’s staff have been paying to those in the community. Many of the seniors spoke with gratitude tinged with awe that Shah and “Dr. K” called them regularly, especially if they noticed that someone seemed uncharacteristically quiet during a Zoom class.

When Mehta lost three family members at the beginning of the pandemic, Shah and Dr. Kalasapudi called frequently to check in. At a time when no one could darken her doorstep, India Home became Mehta’s moral support (“the only thing missing,” she said, “was that they couldn’t give me a hug.”) Shah encouraged her to attend Zoom events, even when Mehta tried to beg off by saying she felt too sad to do so.

“Through that, my life became regular,” Mehta said. Nothing could erase the loss. But the weekly routines of yoga and art classes, accompanied by well-known faces, helped her regain a sense of stability in her life.

Aging and immigrating both eat away at one’s sense of belonging, as generational and cultural shifts become harder and harder to metabolize. This places immigrant seniors at particular risk of becoming untethered from the world around them. By offering culturally competent care, India Home allows people to feel rooted–not only in where they have been, but in where they are.

The organization pays special care to the touchstones of memory, but its draw outstrips a simple desire to retreat into the past. India Home’s greatest gift may be that it gives seniors the chance to live in the present.