In resistance, we are at the neck of injustice, holding our breath, proving our matter.

May 10, 2023

The following hybrid essay is an excerpt from poet Courtney Faye Taylor’s Concentrate (Graywolf Press, 2022). Taylor says, “In this essay, I visit five locations in Los Angeles that are vital to the memory of Latasha Harlins, a fifteen-year-old Black girl killed by Korean American grocer Soon Ja Du after being falsely accused of shoplifting a bottle of orange juice. Harlins’ murder and the following trial, which resulted in no prison time for Du, were inciting incidents of the 1992 Los Angeles uprising.”

One

While writing Concentrate, I was often nagged by the haint of reluctance. It was driven by an insecurity surrounding my lack of proximity to the subject—I was writing about a city I’d never been to, fumes I hadn’t witnessed, a span of years in which I wasn’t even thought of yet.

Girl, reluctance said, all you got is secondhand.

So I head to LA to handle the archive, to stand at the foot of every place I talk up, to earn the facts and their phantoms firsthand.

The epicenter of my curiosity is 91st and Figueroa, the lot on which Empire Liquor Market stood. Empire: a collection of states under one dominion; omnipotent premises; a territory implying power and power implying those who die in the course of courting it.

On 91st and Figueroa stood a structure, a system akin to a kingdom.

Business never resumed after Latasha Harlins was killed inside. Vacancy made it a feasible target. On the first night of revolution, there were several attempts to incinerate it. But Black residents living next door at the Webb Motel stayed up into the wee hours, filling garbage cans with water. Living so close by, barely two feet from the store, they knew the fate of Empire would have also been the fate of their home. To save their own lives, they had to save this monument of brutality. Our survival, inextricable from the structures that threaten it.

In the late 1990s, Empire’s signage was peeled from the building and replaced with that of Numero Uno Market. This is the face that greets me now.

Unlike the stone-white dress of its predecessor, Numero is a pink and green shock to the street. I see a parking lot and a threshold in the back where trucks relieve themselves of cereal, seafood, juice. Inside, three officers linger by the liter sodas. I watch a butcher conceive slivers of meat. A child walks aisles freely, motherless, unhesitant. I make efforts to push my shoulders back but hesitate. I grab a grocery bag, eager for artifact. I hover at the refrigerators, eyeing a camera above the door. I walk around, consumed by questions of configuration. Is everything in the same place? Is this where Soon Ja tended the counter, a gun her clandestine companion? Evidence takes imagination now.

But those who love Latasha do imagine. In 2016, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of her loss, photos slouched against this edifice. Balloons ascended by the fence, dressing the hood in cool helium. On the sidewalk, a pastor prayed for protection, for wherewithal, for a heaven-eyed CCTV.

Numero’s sidewalk was also the location for an interview with Latasha’s aunt, Denise Harlins. Denise helped raise Latasha, a duty assumed in her twenties after Latasha’s mother was murdered in a nightclub. Denise took over the role of hair and heart care. Like many Black women, Denise found herself swept into a motherhood necessitated by grief.

The interviewer asked Denise if she ever got the chance to see Soon Ja Du in the flesh. I watch auntie look up and off camera, ushering in that memory:

“Oh yeah, I saw her…I went to court. Was only one day I missed court and

that day I had to—that night—I had to go to the hospital ’cause both my

glands were swole up so bad, ’cause I was out here doing the work, I ain’t

gon’ lie to you.”

The work of petitions, politicians, protests, and, on the first night of uprising, assisting the Webb Motel—Denise hoped to transform Empire into a center of excellence for South Central children.

All of her work, a resistance. And such resistance menaces the body. In resistance, we are at the neck of injustice, holding our breath, proving our matter. Resistance antagonizes immunity, makes us prone to roadrunner pulse. Epidemiologist Sherman A. James calls this “John Henryism,” theorizing that the tireless effort required to combat racial injustice has a direct correlation to the prevalence of hypertension in Black communities.

Aunt Denise died of congestive heart failure.

You’d be a fool to assume the work of resistance had no part, no say, no hand.

Denise continued,

“The day of the hearing—and it was probably divine

intervention—my glands were so swole I couldn’t go

to court. And I seen it on TV. And when

the verdict came back, I fell on my knees, and I

just shouted to my highest high, and I

was angry.

I knew the fix was in then…

I knew the fix was in then.”

But there are no signs of murder, memorial, or resistance when I arrive. The ground is like any ground. Normalcy devastates. Stillness lies to me about history.

Two

Bret Harte Prep is a beige row of rectangles on South Hoover Street, a nine-minute walk from Numero Uno. Latasha learned here from 1988 to 1990.

At the entrance, a man sits in a folding chair and a woman stands farther back under the hood of the walkway. Every now and then, her pacing brings her nearer the daylight, nearer my knowing. From what I can tell, this pair has the task of welcoming students inside, checking their names against a clipboard list—a pandemic protocol, protection measure.

I won’t disrupt the flow of operations. I came to meet the building, read the marquee’s bold announcements, see that bird up on the roof. Disturbed by the scent of my investigation, she leaves.

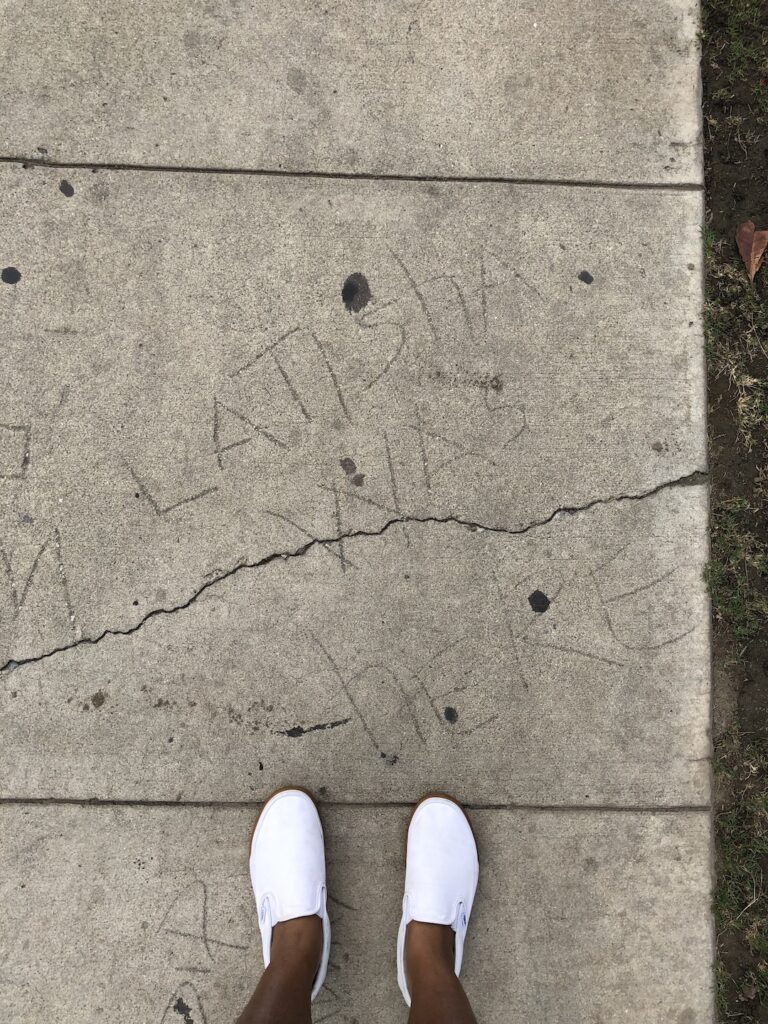

I admire the pavement textured with language, script left by those who passed as the sidewalk dried into permanence. This is how we commemorate—graffiti on the scalps of trains, the lower waists of offices, sharpies to a bathroom stall, twigs ushered through newborn concrete. All of it, our way of reclaiming the narrative of a place, leaving a mark that costs the state money to eradicate.

I read the scratches down South Hoover and back: “BAby,” “Vicious,” “4loc H-WOOD,” “HOLLY,” “MiKE,” “DARRY,” “MAShAWN,” “Westly,” “Dip,” “ALEX III,” “JEROME SMITH,” then, the name I came here for.

I’m encouraged by how Latasha lasts at the door of her education. Someone, maybe even a child who attends Bret Harte now, knew enough to cut her name in an irreversible place. Perhaps this child sat between the knees of an auntie who conjured the name with one command: Don’t forget it. I’m encouraged because, as the saying goes, we live only as long as the memories of others. Black people, as a means of survival, have endeavored to keep long memories.

I didn’t plan on talking. I didn’t wanna bother nobody, but there’s a sudden volume in my relief. So I seek that woman at the entrance. I ask if there are any tributes or plaques or mentions of Latasha at all inside the school.

When Latasha’s name leaves my mouth, the woman’s face presents the problem. It’s the look an accidental wound gives its random, careless maker. I feel it before she says it—a grave has entered our interaction.

“Who?”

Latasha Lavon Harlins, ma’am. Born Capricorn, born cornered. Known for walking in an Empire and never walking out. This horror was first told to me when I entered my body, so as I settle in unsettling skin, I book a room inside her absence. A room of no light and all lore but I’ve entered, a fool, to find her. I’ve entered like Alice Walker in Eatonville for Zora Neale, coming to raise her, name her saint. Just like that, I’ve entered LA to anti-erase, which is a work of resistance. The absent can only live in memory. As the saying goes, if you disremember us, you kill us, and I’m here to resist a second dying. I need you to know this was Latasha’s school, and now her name is a wound in its sidewalk.

Three

On my way to the Algin Sutton Recreation Center, I take in Vermont Vista: Barbary fig in a front yard, the Virgin Mary taped against a window. Two men chatting in lawn chairs on a driveway, a clothesline flaunting mauve sheets behind them.

It’s quiet, foreign to my assumptions, which are all tutored by television.

I’m at the rec center to view a mural of Latasha. Artist Victoria Cassinova painted it on the building’s side face in early 2021. The color, still young. I rub its hem, half-expecting to draw back a rich hand. The only section segregated from the palette are three small doves tarrying off to the right of Latasha’s head, their flight defined in sobering grayscale.

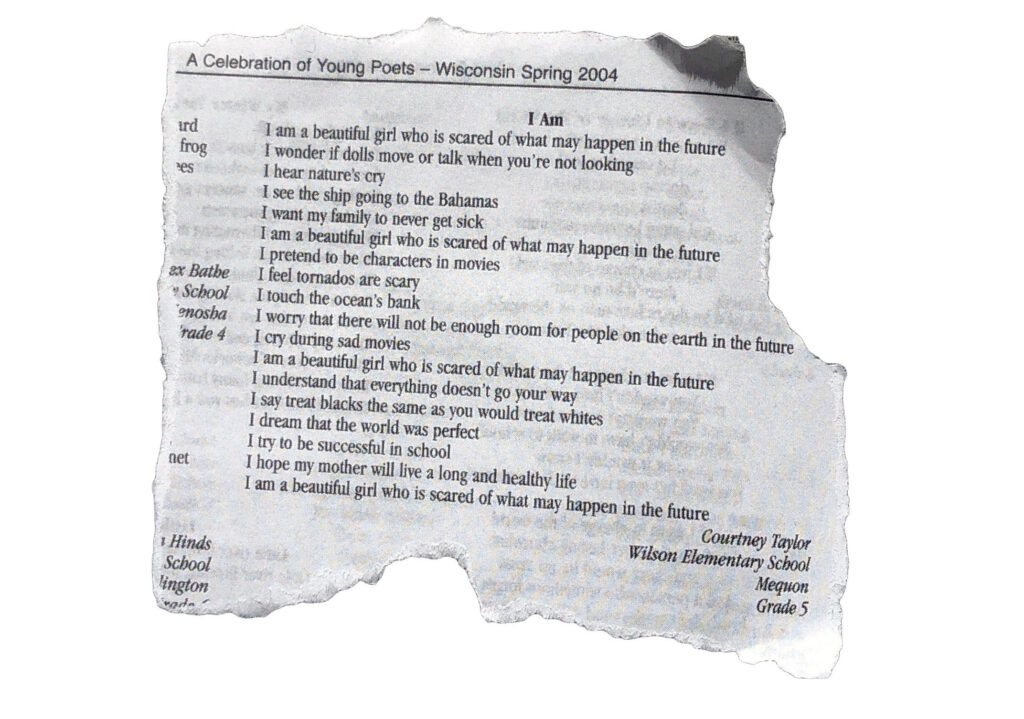

Here, I learn Latasha was a poet. Opposite the doves, Cassinova transcribed a poem of Latasha’s written a month before her death.

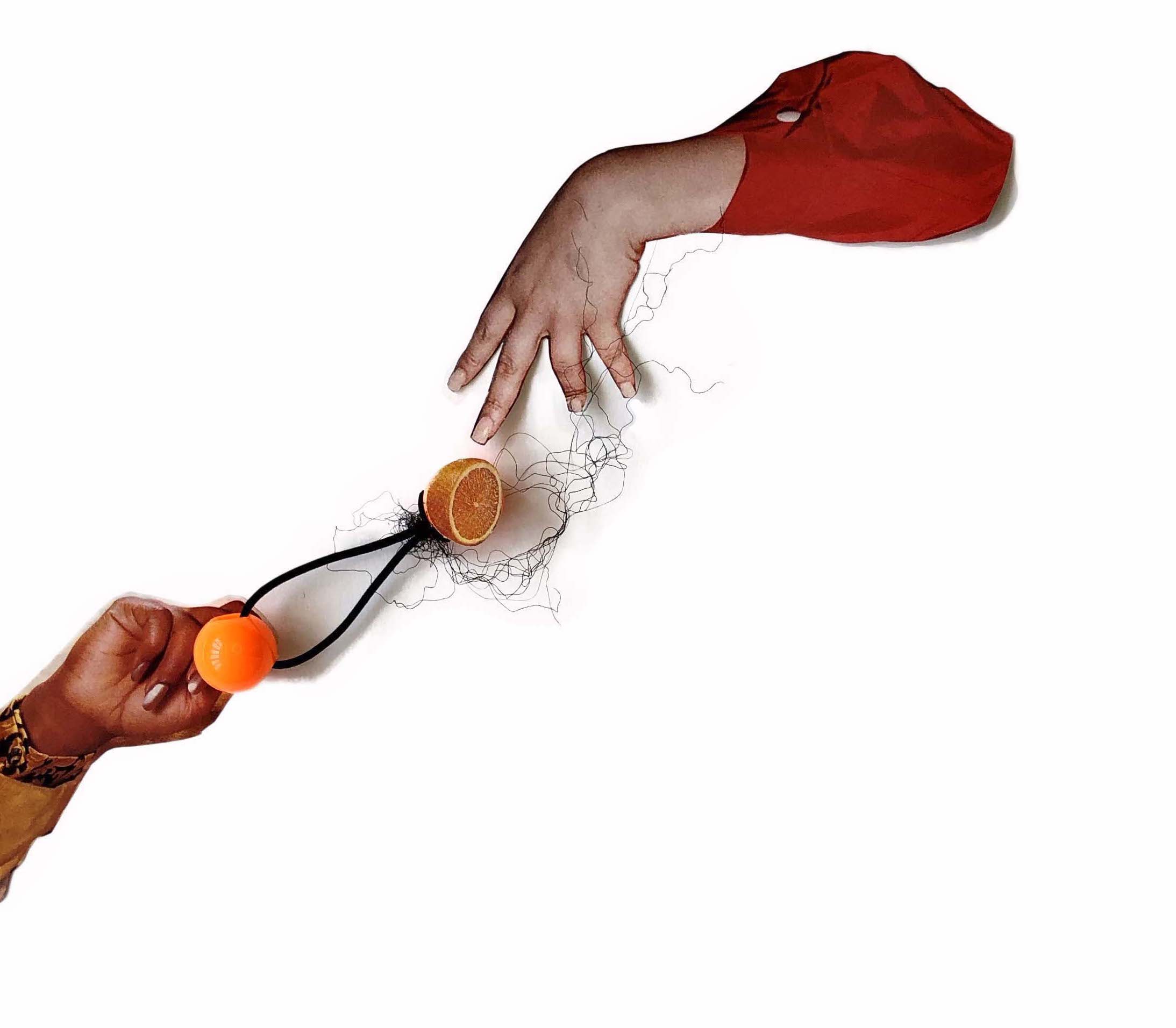

Her piece is reminiscent of an “I am” poem I wrote in grade school. I was given “I am _____” and asked to fill in the blank ten times or so. Often, I switched “I am” for stronger leads:

I wonder _____. I hear _____. I see _____. I pretend _____. I dream _____.

My poem, maimed by fear of catastrophe, of breath in the inanimate, unbridled anxiety. But in Latasha’s work, there’s uninterrupted possibility. Reading her lines, I bear witness to how a Black girl once spoke life into herself:

I have a lot of / talent, she writes.

Latasha could dance, which earned her a spot on the Algin Sutton drill team. Her favorite artist was Bell Biv DeVoe, and so, when I imagine her moves, I imagine them scored by new jack.

I care by / giving what I have / to people who / actually need it

Latasha wanted to study law, a dream had in the aftermath of her mother’s murder. Latasha understood there to be a world of women nonwhite and wounded, a world of mothers refused long, healthy lives. She recognized there to be a world lacking people who cared about this, people unwilling to give what they have.

I am very reliable / and trustworthy

That word—trust. It pops me in the mouth. Soon Ja’s lack of trust is the cause of this mural, the impetus for our public display of memory. But as I see here, trust was something Latasha had already affirmed in herself. Her trustworthiness on March 16, 1991, was fact.

Four

Some yards behind the mural sits the playground where Latasha spent much of her youth. That too is bestowed with her name now.

A child’s murder leaves a hypertrophic scar on the place where it happens. Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson affirmed this at the playground’s unveiling: “Mississippi has Emmett Till. Florida’s got Trayvon Martin. Los Angeles has Latasha Harlins.”

Now whenever the babies of Vermont Vista climb and swing and slide, they will be doing so in the scarred lap of legacy. A child may ask, “Who?” The adults will answer however they do, but their answers will irritate history.

I’m lifted by the mural and the playground, but Algin Sutton is a haunted home for them. It is both Latasha’s adolescent sanctuary and her inauguration into abuse, the place where she was pursued by a counselor twice her age. Jerry was a source of argument in the Harlins household. So you think you grown? You think you in love?

I care by / giving, she writes.

Rape is a room within every cishet man. It’s either locked or onerously doorless. There’s no hotline there, no soap. On the nightstand, a lobbyist kills the age of permission. In the armoire, a god nears the end of its utility. Outside, a chauffeur waits to escort us to the curb of our murders. An auntie is driven nieceless.

I show people I care by / giving what I have…

Aunt Denise pulls up to the rec in ’91 to begin resistance. Her message to this nigga is quite simple: Stop touching my child. When she exits, he’s left with eavesdropping colleagues, and his next move is to disprove. He calls Denise a drunk, says she’s clearly out her mind: Don’t nobody know what she talking ’bout. Don’t nobody want nothing to do with no girl.

So don’t nobody in the rec center make a report. Don’t nobody in the rec keep an eye on Latasha. Don’t nobody in the rec protect this baby. Jerry continues his violence until there is no more Latasha to violence. Don’t nobody consider her a baby?

I know / whatever I set my / mind on something / I can accomplish / I show people…

Men like Jerry get away with murder because their murders are of the innocent. Innocence is a fact you must believe in to save. Innocence is a fact we’ll need a warrant to touch.

Five

When I get to Paradise Memorial Park, the record office is closed. Finding Latasha is entirely up to me.

What I know of this site is its prior owners, their particular horrors—reselling used caskets, occupying single plots with seven or more bodies, stacking skeletal remains behind a toolshed. In 1995, Aunt Denise met with the cemetery board and was informed that her niece was likely one such body affected. She shared her nightmares with the Los Angeles Times:

“All I saw was that big dirt pile

with human bones in it. I didn’t go

to sleep until 3 a.m. I came to work today

and I couldn’t concentrate.”

There’s no inherent logic to the way bodies are lain out here. The dead aren’t categorized by last name or date of departure. The lifeless go wherever there’s space. A patch of grass the width of my palm is all that stands between one unliving and the next.

Without a guide, I’m left in the wreck of my own strategy. I plan to go row-by-row, starting on the left side, working my way to the back in a straight line, then up to the front again. A lawnmoweresque scavenging until I end on the right. I can see the back of Paradise from the entry gate. It’s the smallest cemetery on earth to me. I assume speed and ease.

All the headstones are sunken, little molars pounded in their sockets. The cavities collect leaves, Styrofoam cups, the skin of a baseball, a Toyota receipt, soil. When possible, I dust my shoe across the debris. But some stones are so obscured that it’d take hard labor to see them.

Paradise is home to many Black and Brown ancestors. This makes its ragged upkeep a personal slight, an incendiary grief.

I’m patient in the first half hour, considering each stone as if acknowledgment were an apology for my steps, as if I’m weighing on the skulls and femurs of people who still have nerves, thresholds of hurt.

But soon, time augments. August heat, high and unforgiving. I slow and drag an exhausted confidence. Sentimentality leaves, and the earth quits being precious. I skim headstones and keep right on moving. Like Walker shouting Hurston’s name in that Eatonville cemetery, I beg Latasha under my breath. Now come on, sis. I’m desperate for grace, revelatory light, coordinates conveyed.

After one lap, I’m done with my method. I skip the entire midsection of Paradise and head to the far right, drawn by these tiny handwritten signs on a kudzu brick wall that runs the length of the cemetery. Each sign, a span of numbers.

This makes me think of the memorial ID associated with Latasha’s plot on Find A Grave: 181458514. I’ve always wondered what that number meant. I find a sign on the wall that lists “182-181” and proceed in a line, assuming all graves beginning with 181 will fall in this general vicinity. I’m beside myself with possibility.

I come across the resting place of a baby who lived thirteen days in 1973, two veterans of our last World War, many gone daughters and granddaughters; none of them Latasha.

Now come on.

Then I think to visit all the plots with offerings. Latasha must be Paradise’s most notable soul. There’s a mural, a playground, an Oscar-nominated film in her name. How could her grave ever be ordinary, untended?

I stop by all the stuffed animals, peonies, plastic lilies, windmills, water bottles, a wood cutting of “Family,” a deflated mylar balloon trilling in the breeze.

I come up hardened, hollow.

The driver who comes to collect me is visibly unsettled, realizing he’s arrived at a graveyard. He sees me emerge, pissed off and dark from the tombs, and his first question is if I’m the undertaker.

“I was looking for Latasha Harlins.”

“Who?”

When Walker arrived at Hurston’s house, she sought the neighbors across the street and, after hearing Hurston’s name, that same one-syllable wonder singed the air between them. Who is our greatest expectation. A common, cold refrain in the aftermath of our absence.

When I explain Latasha’s relevance to the ’92 uprising, I can see my driver’s smirk from the back of his head. He was fifteen at the time, Latasha’s age, and recounts the ransacking of a Sears in Hollywood.

“I remember them stealing TVs. All I kept thinking was why…and then I started thinking how I could get me one.”

Back at the hotel, I’m thrust into wonder. Is Latasha still in Paradise? Was her body recovered and moved? A Facebook page called Los Angeles Morgue Files suggests she may be resting in Westwood Village Cemetery. No one at the office returns my call.

Then I come across an article in Whittier Daily News that mentions the lawsuit against Paradise. After the settlement, city officials erected a tall headstone in the very back of the cemetery to honor those affected by its cruelty. I noticed it when I was in there, but thought nothing of it. The stone stands at a distance from all other graves, on an isle of grass.

According to Whittier, this isle is where the majority of the exhumed bodies once rested.

I return to Paradise the following morning, three hours before my return flight. I tell the driver, wait for me, give me three minutes, and I run to the back of the dead.

Whomever. I take it to mean the city is unaware of who its apology belongs to.

Wherever. As if to say the body may be near, elsewhere, erased, wherever—affirming the heartlessness of exhumation, affirming that even if I found Latasha’s grave, I would never find her.

And Forever.

Fraught word, ain’t it?

Excerpt from Concentrate. Copyright © 2022 by Courtney Faye Taylor. Reprinted with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, www.graywolfpress.org