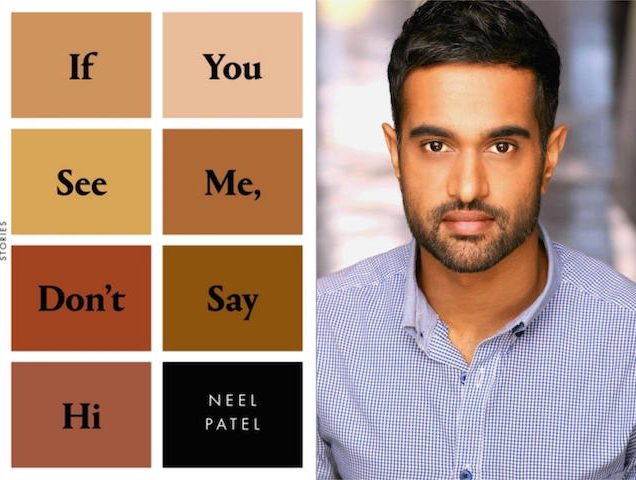

The author of If You See Me Dont Say Hi discusses the draw of the short story, writing with new vocabularies of race, and the immigrant communities of the Midwest.

July 11, 2019

In Neel Patel’s debut short story collection, If You See Me, Don’t Say Hi, which comes out in paperback this week, we meet a wonderful array of characters, nearly all of whom are trying to protect their dignity from a potentially shameful past. One woman’s arranged marriage has fallen apart, but was it because her husband had lied before the wedding, or because she had been unable to cope with the demands of married life? A medical student hasn’t managed to match into a residency program, but how can he hide this from his parents’ friends, and what kinds of power can he exert in the meantime to make up for this loss of face? A young man starts dating a guy who seems to be a wealthy immigrant, but is there more in what his date doesn’t say than in what he does?

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of this marvelous collection is that these are questions that sit with the reader long after they have been asked. Each story sands down the rough stone of a character’s propriety until we get to the smooth, soft center of that person. And yet, even when we can see the characters at their core, even when we feel that what we are witnessing is fascinating us because we’re really looking at reflections of ourselves, we are unable to mete out moral judgment on any of these characters, because Patel doesn’t need the world to be binary, moving between good and bad, right and wrong. The characters make the decisions they do sometimes because they are trapped, and sometimes because they are careless, and we as readers are always left wondering which it will be, or, once we’ve finished, which it actually was.

I spoke to Neel about these intrigues, and how they play out along the lines of the model minority myth, the “Where are you from?” question, and the ways in which the terminologies we use to tell the stories of each other shape who we are.

—Piyali Bhattacharya

Piyali Bhattacharya: So, I’d like to start by saying how much I enjoyed the volume, and also how much my students have enjoyed it. I taught the stories “World Famous” and “Radha, Krishna” in my fiction workshop this semester, and so many of the undergrads immediately asked me for the name of the collection that these stories came from after they read those pieces. I was so glad to see them respond to the work, because while I’d been reading it, I’d been thinking, “Oh, I’m going to give this to so many people!” I think the collection really resonated with a lot of us, and I think part of that is because it is set in some locations that feel very familiar to us as a generation. For example, several of the characters feel really comfortable in in coastal places like California or New York, but many others seem to feel most at home in the American Midwest. Can you talk a little about how the Midwest provides inspiration to you?

Neel Patel: Yeah, absolutely. I grew up in the Midwest, in Urbana-Champagne, where the University of Illinois is. Later, I moved to Chicago, and then about five years ago, I moved to L.A. I was born in Champagne in 1982, and I think we were one of the first brown families in the area. In school I remember I was the only Indian kid, and you know how that is, you have to explain yourself to people, and I’d have to do a lot of, “No, I’m not Native American.” The characters reflect some of those experiences.

It’s so interesting how we end up describing ourselves in those situations. And I feel like it’s changing so rapidly. We’re learning these vocabularies in the last couple of years, and yet, it’s still not that different from the, “Where are you from? No, where are you really from?” questions.

Exactly, and you know what’s interesting is that here in L.A. people are starting to be a little more aware, and yet I’ve been so conditioned to have to explain myself that I get confused about what people are asking me now! Like, I’ll meet guys on Tinder or something, and they’ll be like, “Oh, where are you from?” and I’ll say something like, “Um, I’m Indian? Like from India?” And it’s a ridiculous response, because I’m not even technically from India. I’m ethnically Indian, but I was born in the States, and it’s so confusing. But then one guy was like, “No, I meant like what state, because you said you just moved to California.” And I thought, oh, right.

But of course that was your original response! I totally get that because I feel like we’ve all been conditioned into reading the “Where are you from” question as: Hey, you’re brown, explain that. That conditioning runs so deep that we kind of forget that we’re allowed to say, oh, you know, I’m just from here.

Right, and I don’t know if you’ve experienced this, but I was in a cab recently in Chicago, and the cab driver was Indian, and I could tell that he was from India, and he really wanted to have the “Where are you from” conversation, and I gave him some very convoluted answer, because my parents aren’t even from India, they’re from East Africa, so I gave him this whole spiel, and he got pretty offended, and he looked at me and said, “Why can’t you just say you’re from India?”

And this is the problem, right? I feel like that incident really highlights the ways in which people forget that there can be such prejudice, and such race- or ethnicity-based bias even within immigrant communities.

Yeah, and another part of that problem became clear to me when I was in college, and there was basically no interaction between Indian American students and Indian students from India.

Exactly, and I was always so troubled by that, because as someone who had grown up in a very white space, I came to college looking for brown community, and the South Asian Students’ association on campus is often where I found it. But this is a debate I often have with my friends who grew up in South Asia but went to college in the States, because they tell me that when they came to the U.S., they felt like they didn’t necessarily need to be part of something called a “South Asia Organization” because they felt like their connection to South Asia didn’t have to be mediated through that. And we’ve talked a lot about how I understand where they are coming from, but how, for someone like me, those organizations were really important.

Absolutely.

That brings me to a specific question I had about some of the characters in the book. One of the things that I noticed was that a lot of the characters really identified with the word “Indian,” more than maybe with a broader term like “South Asian,” or maybe a narrower term, like Marathi or Assamese or Tamil, or even a more equalizing term like “brown.” It seemed like for a lot of the characters, the word “Indian” came up a lot, and I’m wondering if you could talk a little bit about that word and how it functions for these characters, and does it differ for each of them?

Yeah, I think that when you’re growing up in that specific community, and there are so few families, that you don’t necessarily identify with your specific group. So for us, we never really identified as Gujarati, because we were friends with families who were Bengali or Telugu. So we all just became “Indian.” And actually, I don’t even remember hearing the term “South Asian” until about ten years ago. So, as we were saying earlier, the vocabulary has changed. The term Indian was kind of thrust upon us, even by our families, so I think the characters are taking ownership over that.

That makes a lot of sense, and it was similar for me; the term South Asian American was something I started using when I went to college, mostly to signal that I wanted to be in community with not just other Indian Americans, but also Bangladeshi Americans, Pakistani Americans, Sri Lankan Americans, Nepali Americans, etc. But even before these vocabularies were available to us, for those of us who grew up Indian American, the communities we knew best were really ethnically and racially and linguistically and religiously diverse, but they were, largely, Indian. And that’s something that I really appreciate about this book, that it allows for the incredible range of what “Indian” is.

Kind of in that vein, you’ve talked a little bit before about how these characters rub up against expectation, and how expectation becomes so important for them. And that’s something I think about a lot. My own anthology is sort of sarcastically titled Good Girls Marry Doctors.

Yeah! My friends were talking about it and I immediately identified with the title.

Well, that’s so interesting, because I immediately identified with yours. If You See Me, Don’t Say Hi kind of implies that between the two people who are running into each other, there is something that shouldn’t be acknowledged, or at least, that neither of them wants to acknowledge. And to me, this is so closely tied to the idea of expectation, or the idea of goodness, or the societal pressure to be a certain way, which of course is a fantasy that nobody can fully live up to. I’m wondering if you could talk a little bit about that title and about the pressure of this thing that we all clearly feel.

I feel like I’m constantly aware of goodness, and being bad, because I’m not a “good Indian boy.” I wasn’t chosen to be in the gifted program when I was in grade school, and this seemed to signal that I wasn’t a good student. And then I didn’t finish college, and that was just not something that anyone around me would even consider doing. You just don’t do that in this world. And then, of course, I’m gay. So I don’t conform to any of those expectations, and so I can’t not think about these issues. What’s interesting, though, is that for so long I believed it was just me, and it turns out, it’s not. A lot of my friends are really high-functioning doctors and some of them are considered the standard, the kind of person that my family has always measured me against on a lot of different metrics. But as I’ve come to know them as adults, it turns out that we’re all equally messed up in the same ways, and I wish I had known that as a child! Maybe I wouldn’t have felt so out of place then. We have this model minority myth, and I think the characters in the book, and the book title, are conscious of confronting that. But it’s so funny with the title because a lot of white people tell me, “Oh, If You See Me, Don’t Say Hi, my god, I love that, it’s so bitchy!”

Wow, that’s not how I read the title at all!

Right, for me, it’s more along the lines of how you reacted to it. When you’re different, especially in high school (and there’s a preoccupation with adolescence in this book), you get recognized for the wrong things. You get recognized for being a freak or an outcast, and to me it’s like, if you’re going to see me like that, then I’d rather you not see me at all.

YES.

The other thing is that in those moments, you want to be simultaneously seen and unseen. Like, you want attention, but you want it for the right reasons. So that’s kind of where it came from.

That makes so much sense, and leads to me to my last question, which is: Did you always know that this book was going to be a story collection? Is there something about short stories that allows to you explore this perspective of being seen and unseen in multiple ways? Did you ever consider a novel?

Yeah, I did consider a novel, but it kind of wasn’t working, and now that I think about it, it might have been because I wasn’t really a writer yet. And stories came a little easier to me–I could finish them, and then stand back and look at them, and see how they were working. So for me, If You See Me, Don’t Say Hi was me becoming a writer, from beginning to end. Now I’m working on a novel, which scares me! But I’m working on other things, too. This book opened up a lot of doors to the worlds of television and film. It’s interesting how other people can see something in you that you never saw in yourself, so I’m really excited for those new opportunities.