If islands are always about escape, can they also come to be about home?

You first feel like an island on a cold winter day, walking down the Upper East Side in Manhattan.

In the three years since moving to New York, you’ve reveled in your anonymity, the way you can slip into the city’s beating heart, your union a rhythm. Absorbed into the heaving mass of moving bodies you feel whole, connected, in ways you have never before. You know what a gift it is to feel seen, but also feel great relief in being invisible.

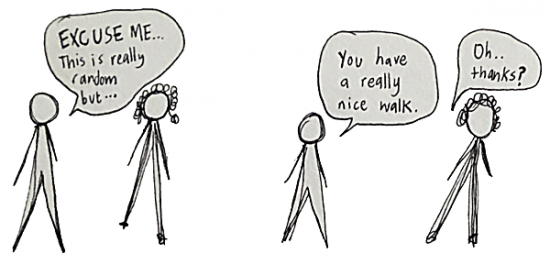

Yet, here you are. Confronted with your difference by a stranger on the street. His eyes furtive, a collision of questions stalling you for a moment.

“What body of water is that in?”

“How come you don’t have an accent?”

“You look North American though?”

You say you’re on your way to somewhere (you always are) and leave.

As you walk to the subway, you turn the word over in your mouth, meditating on its meaning.

Standing on the platform edge, you try it on like a second skin.

Maybe, you are an island too.

Island as Identity

Where are you from?

From from from, the word rings in your head like a humming. Like a bird.

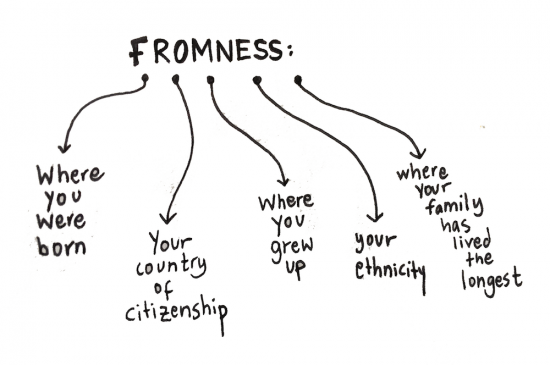

You wonder about this question’s composition.

What does it mean if the answers for each are different?

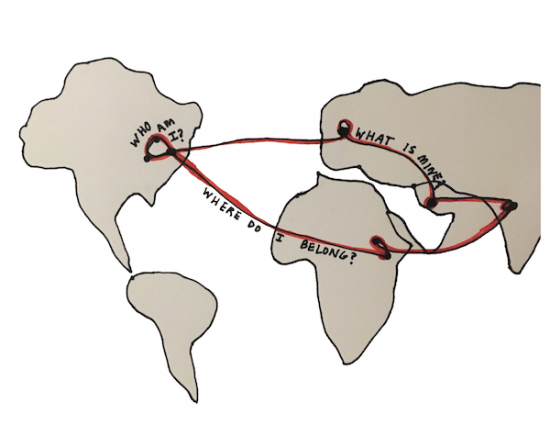

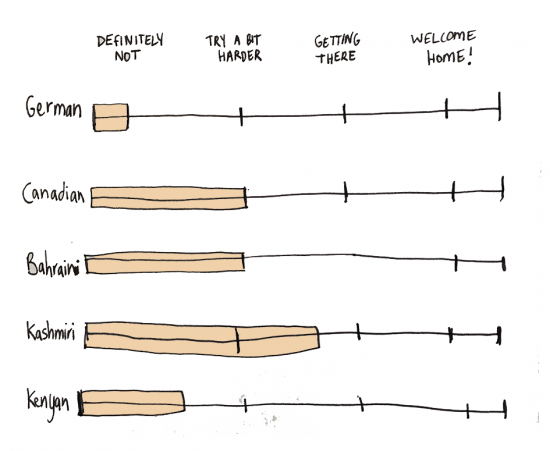

Born in a different country (Germany) from the one you are a citizen of (Canada) which is different from the one you grew up in (Bahrain) which is different from the one you look most like (Kashmir) which is different from the one where your family has spent the most time (Kenya)—makes opening conversations rough.

Your answer becomes a performance. Each time, you adjust it slightly based on audience. You count the five places in your head, checking them off, a tired recitation. An assortment, a buffet, a privilege of places that you should feel grateful for (and most times you do).

A global nomad, she says sarcastically, eyebrows raised in amusement. A citizen of the world, voice a quotation mark. A third culture kid, she nods, analytical, understanding. The titles feel obnoxious, self-indulgent, inauthentic. They just don’t fit.

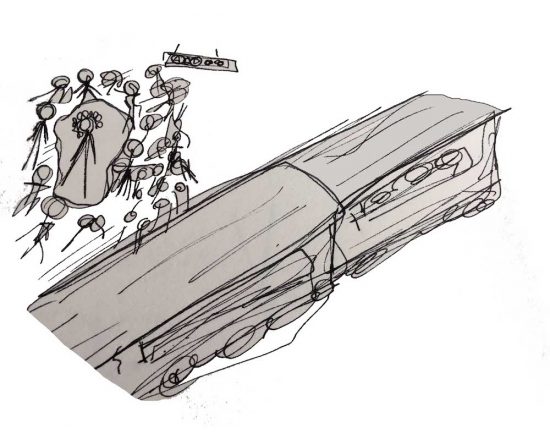

The origin of the island is one of splitting apart. Some millions of years ago, there existed only one large supercontinent. As the earth’s crust slowly rippled, the movement caused several large chunks of land to split and drift apart. The fragments that remained became islands.

You were born from your ancestor’s drifting, a rupture. Their origin, as you know it, was in the Himalayan valley of Kashmir—and the splitting apart in the generations that followed spanned continents. You inherit these stories of migration over dinnertime conversation, piecing together a past that never really feels entirely your own. But still, you search.

There are some days you feel connected to everyone, to everything.

You share fleeting moments of connection with strangers. These brief exchanges are nearly always with those who also feel foreign in the places they are in—as migrants in flux.

As you share a few words of their language, an understanding of a tradition, a food you have both tasted, you become familiar. In the back of taxicabs, at checkout counters, on park benches—you find anchoring in each other. For them, in their memory of home, for you, in your imagining of what it could be. Yet, you know nostalgia is a forgiving space, the murky cloud of remembering an active effort in locating sameness, instead of highlighting difference.

On other days, you feel your lack of belonging like a burning.

Sharp points of starkness—the language you are mocked for half-speaking, the rituals you are ignorant to, how you don’t really look [insert identity], the places you have never lived—all the ways you are told you will never know, never understand, never be. Often, these moments emerge in the countries you are returning to—with those who never left. To them, they see your gaps relative to themselves, and you know, in comparison to their whole, you will always only be a sum of parts.

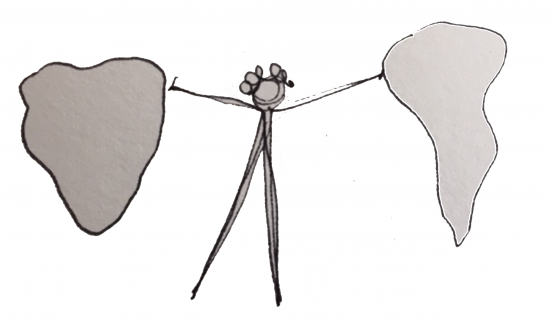

The island lives in constant contradiction to itself. It is at once surrounded—accessible from every side, connected to the endless horizon and the possibility ocean offers—and also exists in complete isolation—separate from other, larger bodies of land.

Born from a severing, maybe it makes sense then that your longing can feel so deep.

Island as Upbringing

You’re texting someone you’ve just met and they ask what Bahrain is like.

Is it like Saudi? He asks. You ask what he means by that.

He answers in a list composed of single words:

desert, oil, conservative, family-focused

?

The question mark hangs in the air. It is not the asking that bothers you, rather the long journey of explaining ahead.

Where do you begin?

The desert island you grew up on is an archipelago, a scattering of 33 smaller ones centered around the largest. Inherent in the definition of a desert island is an assumption of absence, of smallness—but in your childhood memory, you can only recall contradiction: the feeling of both immense space and none at all.

Every week, your mother would drive you to island edge, where the sky would stretch from one tip of the horizon to the next. If the earth was a globe, you would imagine this as the top-half of the world. There was nothing else. With the ocean on all sides, your mind became the place to escape to, the sky a canvas for your imagination.

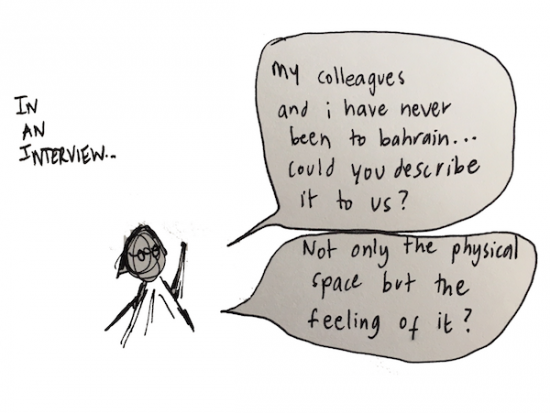

Coupled with this vastness, you also recall a feeling of containment. You are confused by this paradox, and only unearth its origins much later, in an interview in New York where you are forced to clarify its meaning.

In the many iterations of island, you think there is an imagining that yours fits quite neatly into.

You start with the basics:

“It’s a desert…there is a hue of yellow that saturates everything. Some days, the sun is so bright, it bleaches the sky white.”

You settle into the feeling, or a description you think they’d like:

“There is a slowness to it, a sleepiness to the way it moves…” you trail off, unsure.

They nod as though understanding your implicit meaning. What you really mean to say is, it’s nothing like you imagine.

As you take the subway home after the interview, you are frustrated with your molding of island to what you assumed they already knew, or wanted to hear. You wish you had been more honest. Or able to capture the nuance of the place: physical, political, personal.

As you glance up at the closing subway doors, a waft of cold air enters you like ghost, revealing a memory long forgotten.

For a moment, you are transported:

To Funland—Bahrain’s first and only ice skating rink.

It is here where you spent many summer days. The dim oval is illuminated by neon light, pop music blares in the background, and the sound of skates scraping icy skin scratches your brain. In the dark, coolness of closed space, you are free to move. A retreat from the heavy, steady heat. This is what island feels like to you.

For many, the island represents a place to escape to. A utopia to unwind, an idyllic imagining. For you, it is the island itself that you long to escape from. Where physical mobility is limited, then, you seek out the spaces where you can be transported to somewhere else, in search of a different sensation:

Perhaps, then, your feeling is not contradiction at all: where the places of containment offer space for the body to move, those that stretch into vastness—the desert, the sky, the stories—create space for movement of the mind. Both, an effort in motion, a temporary relief from the smallness of where you currently are.

Island as Home

As you return to your apartment later that same evening, you share your encounter with the stranger on the sidewalk with your roommate.

“Just an Island Girl,” you mutter, incredulous.

She listens patiently, before sharing:

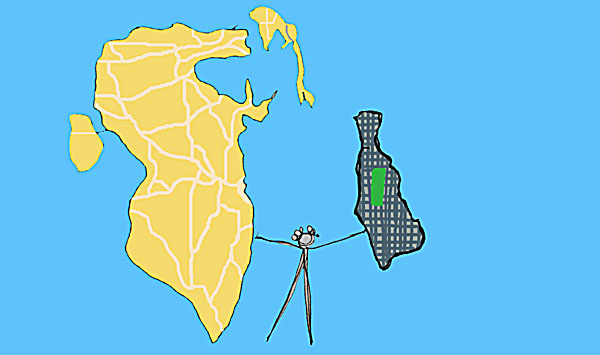

Suddenly, your two islands are sandwiched between you.

The one you grew up on, and the one you now call home.

In the spectrum of you, Island Girl, where does one begin and the other end?

For Manhattan, none of the associations of island initially make sense. In fact, they feel contradictory—the pace, the density, the thronging, pulsing, heaving. There is no place for island in this concrete metropolis, you think angrily. It just doesn’t fit.

Yet, it is here, more than anywhere else, where you constantly feel surrounded. Amid the rush of hot bodies, you feel like home. You can get lost in the movement and still claim it as your own, for the joy and struggle is shared: it is at once yours, and everyone else’s. No one is exempt from feeling small in the heart of rush hour, or from the creeping slowness of a stalled train mid-morning commute, or from the way people seem to spill from every street corner on Friday nights, your only option to wade through.

Maybe, then, that is why you walk slow with wonder. Not because of where you’re from, or where you grew up. Rather, for once, you feel part of something larger, and to revel in this possibility is an island of its own, an escape, even if only in your imagination.