A handful of us scream in recognition like sea flares on a dance floor.

June 16, 2023

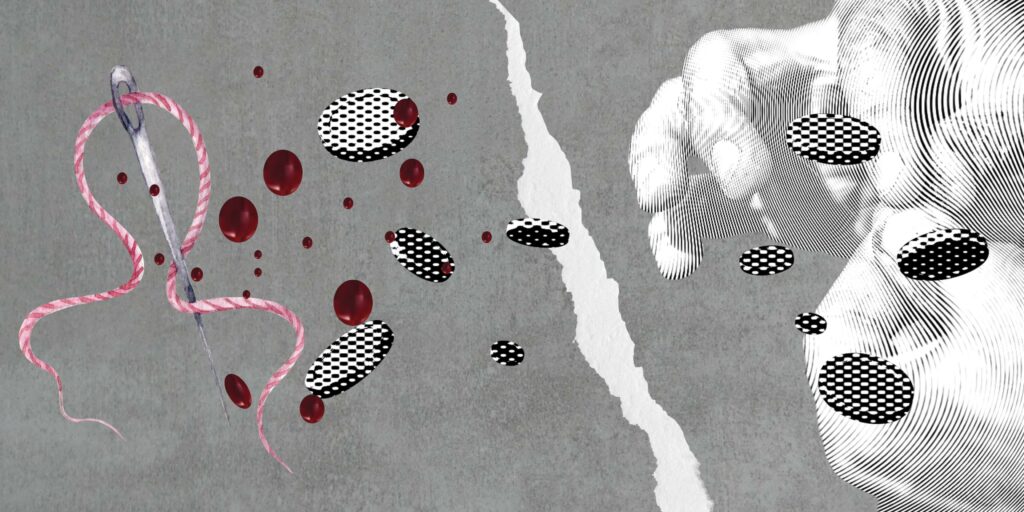

Maddie Zhang is all smiles when I hand her a cup of fresh soy milk from a café in Chinatown. “Thank you so much,” the twenty-seven-year-old Brooklyn-based DJ exclaims. “These are impossible to find unless you’re in the know.” I’m tempted to point out the same could be said of her music—released under the cheeky moniker Maddie Cheung—until I remember the statement is long obsolete. After spending years orbiting the Brooklyn underground with her distinctively Chinese-inspired techno, clips from her set at a DIY Lunar New Year party went viral, stunning listeners with a mashup of Tibetan folk song “Qing Zang Gao Yuan” with Jay Chou’s Mandopop tearjerker “Waiting for You.” In Maddie’s rendition, the two songs, representing discrete musical movements thousands of years removed, are stripped of their instrumental scaffolding to simmer over a pulsating, acid house bass line instead. It’s the kind of anachronistic flourish she’s become known for—recombinations at once vulgar, tantalizing, and addictive. Drawing from the gamut of Chinese music throughout the ages, Maddie conjures a world where the gentle allure of folk melodies, the revolutionary fervor of Mao-era chants, and the viral appeal of modern C-pop collide with club culture of the twenty-first century. Emerging from the margins to the mainstream, Maddie Cheung is the genre-bending, time-warping, borders-smashing DJ the world didn’t know it needed.

I apologize for being late to the interview, blaming it on the lengthy subway trip to Maddie’s apartment in Sunset Park. “Getting here is a real pain,” Maddie acknowledges. “I lived in Bushwick for a bit, but I left because I’ll perish if I’m more than fifteen minutes away from an Asian supermarket,” Maddie says with a straight face before bursting into laughter, flirting with the same kind of hyperbolic humor she employs in her DJing. As a listener, the first thing you’ll learn about Maddie Cheung is that she only samples Chinese music. The second thing you’ll uncover is her ability to twist those samples into both familiar motifs and far-out expeditions that feel sonically, geographically, and temporally distant from other working DJs today.

“Initially, I just mixed bits of Chinese instrumentals and songs into the rest of my mainstream-sounding sets. It sounded horrible, like sprinkling cilantro on vanilla ice cream,” Maddie reminisces. “I needed to go big or go home.”

Born in bustling metropolis Shanghai and raised in comparatively provincial Long Island, Maddie Cheung is part of a growing movement of diasporic DJs paying homage to their cultural roots through music. Maddie isn’t the first DJ to do so—Tzusing, Yung Singh, and Temple Rat come to mind—but her uncompromising approach veers transgressive. Besides a few synthesized sounds, all of Maddie’s samples come from Chinese singers and instrumentalists: a fuzzy definition that includes Chinese nationals, people in the diaspora, and anyone with a notable connection to the region. Besides those parameters, Maddie doesn’t discriminate.

“Some say it’s high art, some say it’s a cheap gimmick,” Maddie muses, as though she sees both sides. “Maybe I’m just trolling.”

As much as Maddie enjoys leaning into disparaging characterizations of her craft, it’s obvious that she’s done her homework—there’s substance to back up her style. When I inquire about her process of choosing samples, she hands me an iPad to show me all the folders of sounds she’s compiled over the years. With names as diverse as “cantonese rap,” “military music,” “songs about flowers,” and “peking opera bangers,” I could tell this wasn’t the artless scavenging of a dilettante or the impersonal register of an archivist. This was the result of a sustained, organic interest in the genre. “I went down so many rabbit holes, trawling books and online forums for recordings from different subgenres.”

I ask which subgenres, and Maddie navigates to a file named “child_of_Havana.wav.” A grainy piano interlude ambles from Maddie’s massive speakers, followed by the high-pitched voice of a soprano. She sings as a father to his daughter, of how her mother died on a plantation and how they’ll dedicate their lives to the Cuban revolution to avenge her death. If the American bandits ever return / I will extinguish them. When the song concludes with the same piano interlude, Maddie says she’s added me to the list for that night’s show. It’s her way of telling me my questions only go so far, the rest must be experienced firsthand.

It’s well past one, and I’m near the front of the booth when Maddie walks in wearing a plain white tee. Another DJ is playing, and I close my eyes, listening for Maddie’s musical entrance. I think I hear it when the sound of the erhu crawls into the foreground, bending and swelling like an ocean. As I’m lulled into its calm, a song I swear I’ve heard somewhere before illuminates the room like lightning, waking me from my reverie. A handful of us scream in recognition like sea flares on a dance floor. For a moment, we pretend we’ve finally found one another.