On Marie Kondo and the painful joy of preserving family history

September 13, 2017

This “literary address” is part of a series of 20 addresses commissioned by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center and the Association for Asian American Studies, as part of the Center’s 20th anniversary celebration and its July 2017 Smithsonian Asian American Literature Festival. Penned by leading Asian American poets, writers, playwrights, graphic novelists, and literary scholars, the addresses assess the state and future of Asian American literature and offer a wide-spanning re-imagination of its place and consequence.

Karen Tei Yamashita’s memoir Letters to Memory is out this month from Coffee House Press.

Your relationship to popular culture and its discontents is on a need to know basis. This is not because you’ve risen above it, but because you are too busy with the past (history) and the future (speculation) to pay attention to the present. What you don’t know about the past is an endless forking back road, but it might give clues to the future, so you are continually running back there to catch up, and it’s impossible to catch up with today. Okay, this might be a big lie. Generally speaking, you are clueless and always lagging at least a decade behind. You tell your son you’re on season 2 of The Wire. That’s great, mom, he says with encouragement. You say, I’m skipping to the last season. I get it; it’s about drugs. French connection in Baltimore. He says, No no, each season is different, a whole new cast. You have to see them all, or it won’t make sense. Oh. You pause, then say, It’s a little dated, and look for the date on the DVD box. 2002. He probably wants to say Duh, but he doesn’t. He’s a nice kid, and this was his generation’s version of your generation’s first generation of Star Trek. Even then, you didn’t really watch Star Trek when it was Star Trek; you let it seep into your conscious present at the time because otherwise you’d have looked really dumb when everyone else was beamed up.

So when your sister comes over to your house and finds you cleaning and discarding stuff, she mentions something about Marie Kondo and hoarding. You query, Marie what? Kondo, she says, and you think about how maybe you knew a sansei named Kondo way back when. But then she says, You don’t know who she is? And to rub it in, She’s translated into a maybe forty languages, published all over the world. When did this happen? Geeze, it’s gotta be a couple a years ago. She doesn’t say, Where have you been? She could, but she knows. You’ve been right here all this time with all your junk.

Your sister opens an issue of New York Times Magazine and points to a cute Japanese woman on a pink background in a pose with her finger pointed up and her foot raised behind her in a small kick. It’s the “J” pose, translated as “joy.” You both imitate what you figure is the pose for the kanji: joy. You scan the article. A book on tidying? It’s great literature, you smirk. Say, your sister reminds you, that woman is laughing all the way to the bank. Right, when have you ever laughed on your way to the bank? So, you ask, you’ve read it? Yeah, she says, picked it up in a pile at Costco for $9.49.

Three million copies sold. A NYT Best Seller. You size up the title: the life-changing magic of tidying up: the Japanese art of decluttering and organizing. Everything is in lower case, like it’s in hiragana, except the J in Japanese. Translated from the Japanese by Cathy Hirano. Where have you been? While you were dozing, the Japanese invented the art of tidying. And it’s not just an art; it’s a method. The KonMari method. Like the Suzuki method. Or Kumon, the math method. It’s like Zen and the art of fill-in-the-blank, except Kondo was a Shinto shrine maid. You think about Shinto shrines completely rebuilt every 20 years. Why not? A complete package for transformation. In the first pages you discover that satisfied clients of the KonMari method have realized dramatic changes in their lifestyle and life perspective, every sort of transformation from the loss of ten pounds to marital divorce. You read that the average amount of stuff discarded by Kondo’s clients can be from 20 to 45 garbage bags per person. In a family of three: 70 bags. At some point she writes that the sum total of all the stuff discarded by her clients would exceed 28 thousand bags and the number of items: over one million. Knowing garbage (gomi) collection in Japan, this staggering number of garbage bags makes you reel. Where did it all go? Into the Tokyo Bay?

“Kondo says, Letting go is even more important than adding, but you know no one said thank you for bringing me joy or I love you before saying sayonara to all the rest of the stuff they couldn’t carry to camp.”

You glance over at the corner of the study that could be your Tokyo Bay, boxes filled with letters, photographs, artifacts, and piles of supporting documentation—a massive dumping place of the thing called your family archive. Since the death of all your dad’s siblings, your cousins have been KonMari-ing the last effects of saved memoria into boxes and mailing them to you. You open boxes that exude the musty air of basements and flutter up dust that could be 100 years old. On page 115, Kondo writes, People never retrieve the boxes they send ‘home.’ Once sent, they will never again be opened. Of photographs, she suggests that you remove them from their albums, look at each one-by-one, then toss. You handle the crumbling spines of old-fashioned obsolete albums, and you understand the urge never to open these boxes, but it’s your own fault. Didn’t you agree to this noble preservation of family history? Besides, there could be treasure in these boxes or the missing code to some family secret. You collate by date the old correspondence, handwritten letters often five pages long, and read through that period when your folks were shipped off to concentration camps with only what they could carry. Kondo says, Letting go is even more important than adding, but you know no one said thank you for bringing me joy or I love you before saying sayonara to all the rest of the stuff they couldn’t carry to camp.

So you fly into Providence, Rhode Island, where your niece Lucy has packed seven humongous UPS boxes of her possessions acquired over 8 years for send-off to LA. The back of her Honda Fit is packed with more stuff, including a hand-built crate with a painting, an official USPS plastic box of sewing material, and a giant stainless steel bowl for kneading bread. You don’t ask about the KonMari spark of joy thing, but you figure, if you hold the bowl, you will feel it. There is room in the Fit for your rollerbag, backpack, rice cooker, and you. Your sister has charted a course across the country through seven of the ten Japanese American internment camps. The goal is to bring the Fit and Lucy home, but you are calling this the incarceration road trip.

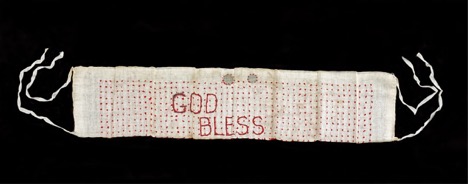

First stop: DC. You meet Noriko Sanefuji, museum specialist at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Noriko will curate the Executive Order 9066: Japanese Incarceration & WWII exhibit scheduled to open in 2017 on the Annual Day of Remembrance. She shows Lucy and you the room and corridors, currently displaying an exhibit on guano, that will house the incarceration exhibit, explaining the complications of limited space, flow of information, and the politics of presentation. Then, you get special entry into the back rooms and basement of what’s known as America’s Attic. Noriko has arranged a small array of objects on a table she hopes to put on display. She pulls on black gloves and carefully caresses the pink crochet of a child’s dress, aged by wear and years. This dress was handmade by a mother in camp, and it is accompanied by a portrait photograph of a little girl in the same dress, standing with her extended family arranged formally in their barrack home. Noriko pulls forward another object, a cotton cloth embroidered with a thousand red knots, nickel and dime secured in the threads, and the words God Bless. An issei mother made this sen nin bari for her soldier son to be worn around his waist to protect him in battle. Each item is handled with gloved care and stored with protective cellophane in acid-free paper and boxes. You remember the ceremonial observance of Kondo’s method plus her practical advice for storing the stuff you don’t toss: Don’t hang; fold. Folding is fun. She writes on page 74, Japanese people quickly grab the pleasure that comes from folding clothes, almost as if they are genetically programmed for this task. You note the sen nin bari, each fold remembered in a yellowed tinge, the sweat and grime of battle, the unspoken story of a soldier’s survival, a mother’s prayer.

Your first incarceration stop: the southeastern edge of Arkansas along the Mississippi River and McGehee, the local town that’s converted its old train depot into the WWII Japanese-American Internment Museum. Susan Gallion, the museum’s curator and host greets you with Southern hospitality and stories of Jerome and Rohwer internees and their descendants who’ve preceded Lucy and you to this moment. Lucy will probably remember the precise context of Susan’s southern phrase: God doesn’t make junk, but you’ll only remember the phrase that will follow you like GPS satellite on that long road trip, the probing matter of human-made junk left behind in camp museum after camp museum. At the Rohwer site, you walk around the remake of a mini-guard tower on a gravel road rising in a field of cotton and push buttons on the placards in order to hear the disembodied voice of George Takei (a.k.a. Mr. Sulu) tell you about life circa 1942 and his boyhood relationship to the present desolation of the landscape and the snakes and mosquito-ridden bayou cleared by inmates. You think, you could be beamed up, now please, but you walk on down the gravel road, trying to ignore the oppressive and scalding humidity, looking for the cemetery. Stone monuments mark bodies left behind and bodies sacrificed in battle, and outside the human burial perimeter, a dog named Papy. You imagine the deep surreal voice of George Takei departing in his starship to that final frontier where no man has gone: God doesn’t make junk.

“Kondo’s admonition that clutter is the failure to return things to where they belong, her insistence on simplicity and minimalism, all this only reminds you of what you assume is the Japanese American motto: Leave it cleaner than you found it.”

Literally and figuratively getting out of Dodge, Lucy and you make your escape in the trusty Fit, then saunter over the Kansas border into the quiet town of Granada on the eastern edge of Colorado. The Amache Museum is a small house on the corner of Goff and Irwin Streets across from a grain silo. You peruse the Preserve America information signs outside museum, and Lucy calls the number on the door. Five minutes later, John Hopper pulls up, and the Amache Preservation Society turns out to be John Hopper and his crew of high school students. John arrives sans students (it’s a school day), but he’s like a one-man show: the principal, the coach, and the AP teacher of the local high school, a former city councilman, and the director of the Amache Preservation Society. The museum began as a high school project; then, John got on the city council to secure the 99-year land lease for the Amache internment site. John says the students do everything except run the tractor to mow the brush and maintain the roads. Too dangerous, he says. He does that work himself, so he’s the maintenance man as well. If the site goes over to the National Park Service, they’ll handle all that. Big loss will be the students won’t have hands-on access to the collection, but, says John, I need to retire; considering his energy, you don’t quite believe him. Inside, the small house is packed with what John says is the largest and most varied collection of Japanese American internment artifacts of any of the camp sites. Usually John’s students run the museum, trained by John and university scholars to guide visitors, curate exhibitions, participate in site archeology. He opens a box with a recent acquisition, a dark green 1944 Amache high school sweater. Some collector contacted John and wanted $1000 for the sweater, said if John didn’t take it, he had a WWII collector waiting to buy it. John said he didn’t have that kind of money, offered the guy $35. The students got mad; they wanted it for their planned exhibit on high school in camp. Eventually, as John suspected, the seller came around for reasonably less. But everything else is donated. We don’t turn anything down. If they send it to us, it has a story and meaning. You observe a glass jug that could be any glass jug except that it held sake distilled locally and consumed by internees; you snap a photo.

Riding north, two days later, at the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center, you meet Darlene Bos, who tells Lucy and you her story of growing up in nearby Cody in one of the camp’s repurposed barracks reshaped into an “L” ranch-style homesteading home. You think you’ve spotted these barracks, likely scattered all over the region as shotgun houses and barns, and maybe haunted, well, haunted with old history since Darlene became curious and studied that history, eventually volunteering to work at the Heart Mountain site. Now she’s the center’s Marketing and Development Manager. From childhood, she says she argued with her father, a US military veteran. When the interpretive center finally opened, and both her parents had also volunteered their energy to build the meditation garden, her father finally said to her, You were right. She admits she’s always on the look out for visitors like her dad, hoping to change their minds. She says, I love my work. The Heart Mountain center is impressively curated, packing history into a small and concentrated space, deeper layers of documentation and oral histories for visitors who care to take the extra time. In the foyer, a windowed outlook to the mediation garden, visitors have strung tanabata-like on a barbed-wire fence, replicas of the internee nametags, leaving behind messages of their impressions and wishes. As you leave, you note the box of Kleenex discretely placed on a bench.

Two days later, passing through Minidoka in Idaho, Lucy and you take the Fit south into Utah to a town called Delta and the camp site named Topaz, the jewel of the desert. It’s a desert all right. The clear blue sky sweeps the horizon, sun and hot wind unrelenting. You squint across a landscape of salt desert shrub and greasewood and follow your guide Jane Beckwith’s sure steps, sinking into the parched and cracked crust of soil that churns into fine dust. Jane points to the outline of rocks and stones that mark the garden and threshold of barrack 6-3-F in block 6 and ushers you through an imaginary door. You walk around the 20 by 24-foot perimeter of your family’s confinement, home to 13 people from 1942 to 1945, and scuff around in the remains of rusty nails, wood scraps, broken pieces of cement foundation. Jane picks up rocks and identifies them geologically. What you learn is that every rock and stone had to be brought to the area by the internees to create the gardens that have since disappeared. Every rock and stone. You want to find a piece of pottery or perhaps the rusty hardware of your family’s abandoned waffle iron, but even if you found it, you’d be prohibited from taking anything from the site. All that past broken and discarded stuff, every rock and stone, belong to the place, to be left untouched, scorched by sun, weathered, and returned to the earth, an archeological site whose desolate surface memory is now a sacred memorial. Kondo’s admonition that clutter is the failure to return things to where they belong, her insistence on simplicity and minimalism, all this only reminds you of what you assume is the Japanese American motto: Leave it cleaner than you found it. Kondo writes, No matter how wonderful things used to be, we cannot live in the past. The joy and excitement we feel here and now are more important, but you have the deep urge to exchange the word “wonderful” for “awful,” and sit in that spot and weep.

“You know you cannot hold each item and feel for the spark of joy, kick your foot back and point your finger up in the joy position. If there is joy, it is a painful joy.”

To be fair to Kondo, she could be your daughter (okay, unfair), a yonsei raised in a capitalist consumer society with great privilege (no war, no refugee boat, no trail of tears, no depression), but she is still is a product of the long post war. You wonder what people in what 40 languages have required Kondo’s advice. Can the trauma of the hoarder be undone with the methodic and ceremonial movement of clothing, books, paper, miscellany, and sentimental value rendered into honorary trash? She says, The question of what you want to own is actually the question of how you want to live your life. This could the most succinct clarification and synthesis of Buddhism and Marxism, the revolution you’ve been anticipating. Voilá.

Kondo might say that this stuff in your family archive and this stuff in all these internment museums were parted with to launch them on a new journey. You cogitate the joy spark thing, and you think about simple furniture made from wood scraps, the pink crocheted dress, the sen nin bari, the green high school sweater, the jug of sake, and the waffle iron you know your family smuggled into camp. You know your family had to gather precious eggs, milk, butter, flour, and syrup, and they convened in the ironing room for access to an electrical outlet that wouldn’t blow the barrack fuse. All this for a small celebration made special probably by the only waffle iron in camp.

Jane Beckwith pauses with a last story. She remembers bringing a class of children to visit the Topaz site and one boy who was particularly rambunctious, jumping and noisily running about. A girl also his age admonished her classmate, be quiet; she advised him, Don’t you know? They are here.

Lucy and you are home now. Lucy opens the garage door and gets greeted by the seven humongous UPS boxes plus, on the porch, a narrow box containing her bicycle. She announces that one of her next projects is to go through the stuff in her family storage unit. You look at your personal Tokyo Bay, a landfilled space of junk you cannot abandon. You know you cannot hold each item and feel for the spark of joy, kick your foot back and point your finger up in the joy position. If there is joy, it is a painful joy. You ponder the thought that Lucy has beamed up most of it into digital space and reorganized it into a website story. A new journey. You reflect on the lives of Jane Beckwith and John Hopper and every other curator and keeper of history along your incarceration road trip, and you think that keeping the stuff, saving it, might also be a way of transforming your life.