There’s no shame in loving durian at this New York City haven.

January 22, 2020

It was the flash of yellow that caught my eye as I speedwalked one summer up 6th Avenue in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. The sign out front read: “MK International Group Inc.”, which sounded to me like a software company or an office supply importer, but the interior hinted at something much more appealing. Through the window, I could see the vivid, pineapple-yellow walls and counters, and posted on the storefront glass were large, lurid photos of sliced-open durian and its plump, fleshy pods.

I was running late to volunteer for a local Asian American women’s nonprofit in the neighborhood, but later that afternoon, I returned to the store with a few of the nonprofit’s staff. All of us were women of Asian descent, and the durian had piqued our interest.

As we opened the door and stepped into the sparsely decorated interior, the fruit’s aroma wafted toward us—a warm, caramel scent with a musky, almost smoky tang. The shop’s bare, blond-wood tables and clean metal chairs toward the rear lay empty on this late summer afternoon.

One of the nonprofit’s staffers was from Singapore, and she was clearly a durian enthusiast. She scanned the menu, explaining items like cendol, a shaved ice dessert, and what we could expect of the taste. “I don’t think it smells bad at all,” she said, inhaling deeply. “I love it.”

I was excited to get another taste of this delicacy, a rare treat in New York. A few years ago, I’d tried durian for the first time in smoothie form during a trip to Honolulu’s Chinatown. A local friend had brought me to the Hawaiian shop, which, like this one in Brooklyn, kept durian’s slippery pulp cold. This meant I never experienced its fresh, unadulterated aroma, which mostly comes from its outer rind; just the rich, creamy texture and surprisingly filling, savory-sweetness in a smoothie.

MK International’s wares did not come cheap. The large, fresh durian, wrapped in yellow netted bags in the cold case near the register, was priced at $10 per pound, which meant a whole fruit would cost at least $30. The “Musang King durian cendol ice” cost $10, a price that I’d also balk at paying for patbingsu, a similar Korean shaved ice dessert (which does not contain durian). I settled on the slightly cheaper durian smoothie, $9, which I let a fellow Korean try.

She took two tentative sips through the straw, then passed the plastic cup back to me.

“I’m good,” she said. She didn’t like it, but she couldn’t really explain why. She also didn’t resort to any exaggerated theatrics to demonstrate her distaste.

I took another sip, trying to put my finger on the flavor. “It’s… savory… smoky,” I ventured, connecting the sensation in the back of my throat to a scotch whisky tasting.

Whenever anyone writes about durian, “the king of fruits,” the first thing they mention is the smell.

“Durian is notorious for its very unfruit-like aroma, a powerful smell that can be reminiscent of onions, cheese, and meat at various stages of decay!” writes Harold McGee, the renowned food science and cooking expert, in his book On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. He adds: “At the same time many people prize it for its delicious flavor and creamy, custard-like texture.”

Other, less diplomatic writers compare the fruit’s scent to: “completely rotten mushy onions” or “road kill wrapped in sweaty socks.” Search YouTube, and you’ll turn up countless videos in which self-styled culinary daredevils clumsily manhandle and deign to taste the fruit, often gagging or spitting it up, although there are a few outliers who will appreciate its flavor.

Of the most popular, mostly American-made videos, very few appear to include tasters from Southeast Asia who might be familiar with durian and its accompanying olfactory sensations. The best videos, like this one from Great Big Story, include the perspectives of people who know and love the fruit, like Malaysian farmer and durian seller Chang Teik Seng.

As for its looks: Imagine a stemless pineapple on steroids, and you’ll start to get a sense of the shape and heft of a durian. Grown in Southeast Asia, it’s sized somewhere between a cantaloupe and a watermelon. Nestled inside its yellow-green, tough, spiky exterior are alien-like pods of fruit that are roughly the size of an adult woman’s hand. On their own, the custard-soft pods look like smooth, pale yellow sacs of fish roe—it’s surprisingly animal-like for fruit.

The first time I heard about durian, I was a teenager at church in the plush, Northern Virginia suburbs just outside D.C. where I grew up. My family was new to this congregation of Korean Americans, which had just sent a privileged handful of youth on an expensive missions trip to the Philippines (what purpose they had proselytizing in a country that’s already majority Christian, I don’t know).

The newly returned junior missionaries, whose skin had warmed to a golden brown in the Southeast Asian sun, stood before the rest of our youth group and presented their photos of the prayer meetings and church services they’d held for the slightly browner locals.

At the end of the presentation, one of the Sunday school teachers who had gone to the Philippines asked those of us in the audience, “Who here has ever heard of durian?” She wrinkled her nose, as if to signal her disgust to us in advance.

I looked around the meeting room filled with fellow teenage Korean Americans and Korean immigrants. None of us raised our hands.

“It is the stinkiest, stinkiest fruit,” she said. “We tried it when we were in the Philippines, and it smelled sooo bad.” She waved her hand in front of her nose, pantomiming the odor, then held up a crinkly, clear plastic bag filled with what looked like individually wrapped pies. “We brought back durian tarts for you guys to try… if you’re brave enough. Since they’re baked, they don’t really smell at all.”

She passed the bag around, and the adventurous among us took one. When the bag reached me, I inspected the hard, dry-looking discs in the package. I had no idea what durian looked like, how it tasted, or even how it smelled, other than “bad,” according to the Sunday school teacher. I decided to pass.

Growing up, I often felt that twist of shame in my chest whenever people commented on the smell of my parents’ food. It’s a common memory among the children of immigrants, from the Italians (and so many others), who appreciate zesty garlic, to the Koreans like me, whose open refrigerator doors waft out kimchi aromas.

Immigrant-food shame, especially among Asian Americans, has become such a tired narrative trope that once I heard Eater NY editor Serena Dai rightly call for a moratorium on the “Asian American lunchbox” stories.

Sometimes I wonder if the outsized reactions to durian come partly from the ignorant uninitiated (see: YouTube), and partly from some marginalized people’s desire to point out even further marginalized people and their foodways, as if to say, “Look, there’s something out there that’s even stinkier than our food!” Both groups rub me the wrong way.

To me, it’s worth considering the how and the why behind durian’s popularity. One Gastro Obscura writeup points to how the fruit’s richness and high fat content offers “a creamy texture that was historically hard to come by” in the traditional, low-dairy Southeast Asian diet. In his particularly nuanced report, PRI’s Patrick Winn quotes Bangkok-based author and food writer Chawadee Nualkhair as saying, “People are crazy about durian the way people are crazy about any hard-to-grow, valuable item. Like people are crazy about caviar. Or people are crazy about foie gras.” Winn goes on to explain that mainland Chinese consumers’ love of durian has led to unprecedented demand for the fruit. The trickle-down effect of that popularity could explain why MK International has set up shop in Brooklyn.

In the year after my first visit to the Sunset Park durian cafe, I visited a few more times, spoke to the staff, and arranged an interview with one of its owners and noticed a name change (from MK International to MK Durian or MK Durian International, according to Facebook and Yelp, respectively).

Sunset Park, with its relatively low rents and large Chinese population, made for an ideal neighborhood, co-owner Raymond Wong, 44, told me over the phone, adding that he thought the fruit appealed to local Latin American residents, too. “Now, about 75 percent of our customers are Chinese, but I can see an increase in Americans and other races.”

“The reason we came up with this cafe is that if you live in an apartment, you can’t bring durian in,” said Wong, a resident of Flushing, Queens, whose family comes from Malaysia. The fruit is famously banned in many Southeast Asian hotels and on Singapore’s subway system. “The neighbors will complain that there’s gas leaking.”

He relayed an anecdote to me—“It’s happened before!”—in which a neighbor mistook one family’s durian feast for a gas leak and called the New York City fire department. “Con Ed spent the whole week looking for a gas leak,” Wong said, “so I thought it would be a good idea to make a good place for durian lovers.” As durian’s popularity has grown, it’s become more available at Asian grocery stores and fruit stalls around the city, including Manhattan Chinatown’s famous Durian NYC, but Wong said that he didn’t know of other businesses that allowed customers to enjoy durian on their premises.

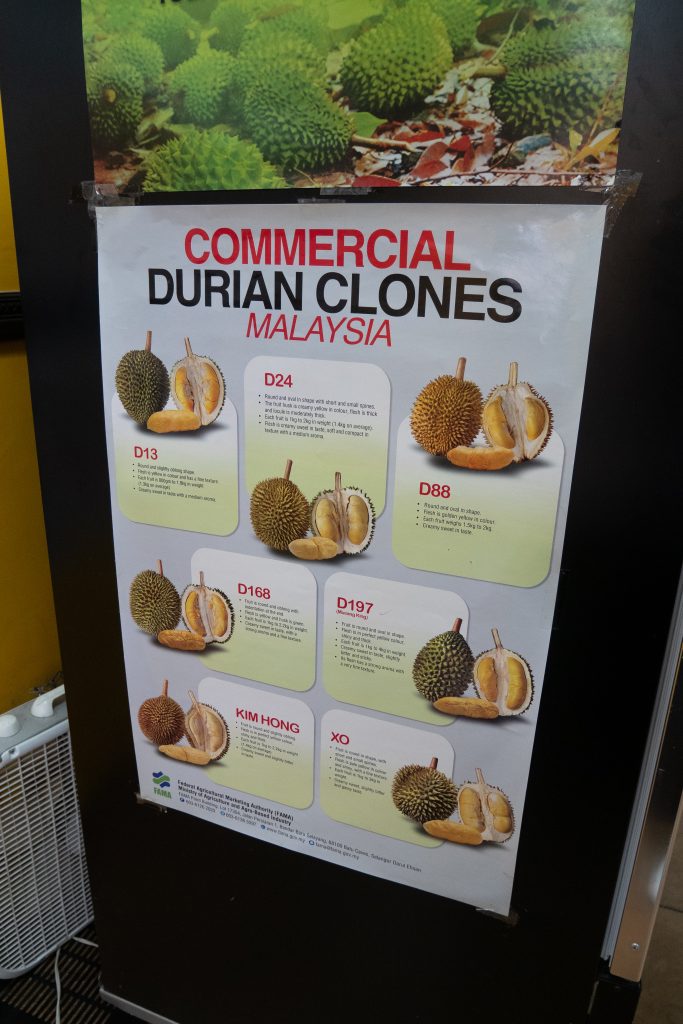

The “MK” in the cafe’s name stands for Musang King, one of the most prized varieties of durian. “It’s the most consistent species,” Wong said. “It’s so yellow, with a creamy texture as well. Inside, the meat is sweet, and the seed is always smaller than other species.” A poster in the cafe pointed out other varieties, like the XO, the D-88 or the Kim Hong.

“Here, you don’t have to deal with how to open the durian,” he said. An expert durian handler knows to make shallow cuts along the thorny outer rind to create an opening large enough to scoop out each whole, cocoon-like pod. In a badly butchered durian, as the videos show, the flesh turns gooey. Maybe it’s this physical mishandling of durian that’s to blame for its bad reputation.

I broached the subject of durian’s aroma with Wong, careful not to offend. He seemed unfazed as he answered, though. “This can be described as either you like it or you hate it,” he said, nonchalantly. “If you like it, it smells really good. If you don’t like it, if you’re not used to it, it smells like gas leaking.”

He explained that it could be an acquired taste: “Slowly, if you learn to like durian, then you will like the smell as well.”

Wong told me that his favorite way to eat durian is to mix the flesh up with white rice. “It’s a taste of my childhood,” he said, wistfully.

While I’ve spotted only a few customers in my visits to MK Durian, I did connect with some via Yelp. The café seems to draw the most customers during limited-time, all-you-can-eat durian specials, which staff advertise via Facebook.

“I went in because at the time they had all-you-can-eat durian,” one customer, who asked to be identified as Siny U., told me via online message. “I live nearby and I love durian.” When I asked Siny her thoughts on the fruit’s polarizing aroma, she wrote: “You either love it or you don’t, there’s no in-between. It tastes like ice cream if you like it, but smells like poop if you don’t.”

For my part, on one of my visits to MK International, I lingered at a table over a frozen cup of Musang King durian puree, which includes a few additives like whipping powder and emulsifiers. Solid at first, it softened into a smooth, ice creamy texture, with a lingering, not-unpleasant sulfurous flavor that I could taste when I exhaled with my mouth closed. Just a few bites felt satisfying and indulgent, and I snapped the lid back onto the cup to bring home for my husband to try.

Tina Xue, 33, another customer whom I connected with online, told me that she thought durian in dessert form was more mellow, as the cream and sugar “fade out the flavor,” which she doesn’t particularly like. Xue, a Washington Heights resident, said that she popped into the shop when she happened to be in Sunset Park.

“My husband is the one that loves it,” she said of the fruit, “but he is French, and it’s akin to blue cheese.” She added that it’s interesting to her to see the fascination over durian, despite its odor. “I think stinky tofu from Taiwan and China smells way worse,” Xue offered.

Before leaving MK Durian, I perused a metal rack of pre-packaged durian-flavored treats, from which I picked a package of durian-infused instant coffee to share with friends. The coffee ended up tasting like a slightly more dank version of the milky, sweet instant coffee packets that you find all over Asia.

According to Harold McGee, durian “apparently evolved to appeal to elephants, tigers, pigs, and other large jungle creatures, which are drawn to it by its battery of powerful sulfur compounds.” When I got home and uncapped the durian to have another taste with my husband, my dog practically shoved us to the side to get a closer look at the cup in our hands. Once I was finished, with durian still on my breath, she clambered to sit next to me and lick my face. She may eat kibble for every meal, but there was something about durian’s appeal that wasn’t lost on her animal senses.