The recovery of my familial and cultural heritage has always been continual, albeit somewhat stop and start—just when I think I have unearthed the final root, my spade hits another one with a meaty thwack.

August 26, 2020

“By the virtues that I once possessed, I demand this from you. Hear my tale; it is long and strange”

—the monster from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

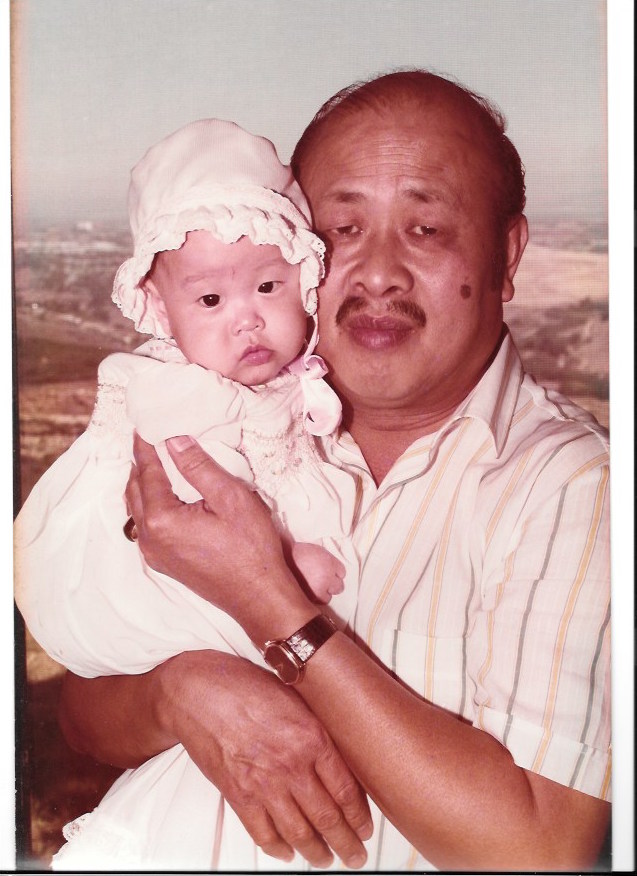

My maternal grandfather—my Kung Kung—passed away at the age of 89. After the wake and funeral were over, I took a framed photograph from his bedroom as a keepsake. I knew the picture well. Before it migrated to a shelf in the corner, it used to sit atop the enormous TV at the foot of my grandparents’ bed, where I used to lie as a child, amid pillows and bolsters, keeping them company after dinner. The photo is of baby me, in my baptism clothes, in Kung Kung’s arms. His cheek is pressed against my frilly white-bonneted head. On the hand cradling my chubby baby arm, he wears a heavy gold ring. His head is still sparsely carpeted in black hair. His moustache—which he was so proud of in life—is black as well.

The photo flew back home with me to Sydney in my suitcase, still in its original clear plastic frame, swaddled in clothes for protection. When I unpacked, I realized that another photo had stowed away with it, a sliver peeking out from behind Kung Kung and me. I slid it out and found a different picture of my Kung Kung—this time at an official business function. He is with the late Indonesian president-dictator, Suharto, their hands clasped in a two-handed salam. In the background is a queue of other people who have already filed past and greeted the leader in their turn. My grandfather’s grey-suit-clad shoulders are stooped in a slight bow and he looks positively thrilled. Suharto’s smile—his infamous trademark—is one of benevolence.

I tucked the photo back into its hiding place. I remained kneeling in front of my suitcase, unsure of what to do next. Never had I expected to be confronted with such clear evidence of my shameful lineage. Exhibit A: me and my progenitor. Exhibit B: him, in turn, with his creator—the man who made him and a handful of other ethnic Chinese men into some of Indonesia’s wealthiest tycoons. The tycoons who were prosperous proof that the worst stereotypes about Chinese-Indonesians were true.

Maybe the discovery shouldn’t have surprised me. For some reason, the recovery of my familial and cultural heritage has always been continual, albeit somewhat stop and start—just when I think I have unearthed the final root, my spade hits another one with a meaty thwack.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

I didn’t identify as Chinese-Indonesian for the first twenty-or-so years of my life. As an adolescent, I would certainly have said my father’s side of the family was Chinese-Indonesian, and I would definitely have said my grandparents’ generation on my mother’s side of the family was Chinese-Indonesian (my mother and siblings were raised in Singapore). Yet I was encouraged by my family to think of myself as either Chinese-American (thanks to my US passport) or simply Chinese. When I went away to college in the US, I began telling people I was Singaporean because I’d lived there for eight years, and because it became patently clear to me that I wasn’t “American” in the way my other Asian-American classmates were. And even though I had lived in Indonesia for six years, I didn’t feel any more Indonesian because of it. While there, I’d been sent to a private English-language international school. My closest friends were from Malaysia, Hong Kong, Singapore, and the Philippines. (Or so I thought at the time. I found out as an adult that many of them had been Chinese-Indonesians pretending to be Malaysian or Singaporean.) My family never mentioned that I was Indonesian at all, and my woeful Indonesian-language skills didn’t help. It was only when I went to graduate school at the age of 21 that I began to realize this omission of theirs—and to get an inkling of why they never emphasized my affiliation with Indonesia, and why I myself had never dared to connect the dots.

My desire to recover the Indonesian side of my heritage sprang initially from pure pragmatism. The English PhD program at UC-Berkeley required students to gain a reading knowledge of two languages besides English, or advanced proficiency in one. I was lazy and wanted to fulfill this requirement as quickly as possible, so I decided to aim for advanced proficiency in Indonesian, which I already had a very basic knowledge of, hearing it spoken around me as a child. I enrolled in intermediate Indonesian-language classes. Under the mentorship of Dr. Sylvia Tiwon, an Indonesian professor in the South and Southeast Asian Studies Department, I began reading Indonesian literary works. I decided to write my dissertation on colonial and postcolonial representations of the Malay/Indonesian archipelago. I devoted a chapter to Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s Buru Quartet, and another to Timothy Mo’s The Redundancy of Courage, which is set in a thinly veiled Indonesia-occupied Timor Leste.

Doing research for these two chapters led me to learn more about modern Indonesian history and culture, which I’d been almost entirely clueless about beforehand. For the first time, I became aware of how my family fit into the landscape of history. I realized that the island of Bangka where my maternal grandmother had grown up, was where large numbers of Hakka-speaking Chinese had migrated in the 18th and 19th centuries to work in the tin mines. I realized that the reason she and my grandfather often spoke Dutch to each other was because they had each attended Dutch-language primary schools that had been set up specifically for the Chinese. (The schools had been segregated according to race.)

It finally hit home that the times my father had spoken about his school shutting down when he was little referred, in fact, to the mass closure of all Chinese schools nationwide, along with Chinese-language organizations and publications. These were part and parcel of the nationwide ban on public displays of Chinese language and culture implemented after Suharto seized power in 1965. I became aware that my surname—Tsao, or 曹—was unusual for a Chinese-Indonesian to have on official documents. My paternal grandfather and uncle had long since adopted the more Indonesian-sounding “Santoso.” All Indonesian citizens of Chinese descent were pressured to “Indonesianize” their names during the Suharto era, supposedly for the sake of cultural assimilation and national harmony. My father followed suit belatedly, in the mid-1990s, during the divorce proceedings with my mother when the court refused to accept the discrepancy between his and his father’s last name and changed it to Santoso for him.

Reading about Indonesian history also yielded more information about the anti-Chinese violence of May 1998, which occurred during the final days of Suharto’s three-decade-long authoritarian reign. I knew these riots. Not firsthand. I had witnessed them via TV from a hotel room in Singapore. My mother had been organized and well connected enough to get her, us children, and our housekeeper-nanny on a flight the very morning that the unrest in Jakarta’s Chinatown broke out. (My mother and us children relocated to Singapore effective almost immediately. My paternal grandparents would eventually move to Toronto to join my father’s other brother. My father still lives in Jakarta.)

I had always known that the attacks had targeted the ethnic Chinese—that it had been Chinese-owned shops singled out for looting and Chinese women singled out for raping. But I hadn’t known that the anti-Chinese violence had been orchestrated by the military. And I hadn’t contemplated until that point, deep in the subterranean stacks of the Berkeley main library, the possibility that this event may have contributed to my unconscious decision to not identify as Indonesian myself. Indonesia and Chinese were not commensurable, screamed the events of May 1998 in fire and blood. In fact, when I surveyed what I had learned about state-sanctioned discrimination against the Chinese in Indonesia, it made more sense to me why my family hadn’t emphasized my Indonesianness. I was privileged enough to have a choice between being “American” or “Singaporean”: so why encourage me to select an option most hostile to people of Chinese descent?

In a simpler version of this tale—how I reconnected with my Indonesian heritage—this would be the ideal place to stop: the revelation that systemic racism and violence against the Chinese had a hand in preventing me from identifying as Indonesian. Poor me. But as I’ve said, the process of my self-recovery is apparently never-ending. As I continued to read, to delve, I realized that there was more. And it marred any self-portrait of pure victimhood I might be tempted to paint.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

Because the subject of ethnic Chinese stereotypes came up in the Timothy Mo novel I was writing a dissertation chapter on, I researched them as well. I had some knowledge about such stereotypes already—perceptions of the Chinese as money-minded, shrewd, and hoarders of wealth—but I learned that their roots were deep. In fact, during the colonial era in Indonesia, Dutch administrators segregated the Chinese-inhabited areas from the native population for a time in order to protect the locals from what they believed were the sly and calculating ways of the Chinese. (Protests from the Chinese themselves were the only reason why such segregation was eventually repealed.)

I also found out that similar perceptions of the ethnic Chinese existed across Southeast Asia as a whole, reinforced by colonial Europe’s deployment of Chinese traders as merchant middlemen. In fact, in 1914, King Rama IV of Siam published a whole essay about the threat posed by the clannish and mercenary ethnic Chinese, titled “The Jews of the Orient.” In 1970, Mahathir—who would later become Malaysia’s Prime Minister—described and proposed solutions to the ethnic Chinese “economic stranglehold” over the national economy in a book called The Malay Dilemma:

For the Chinese people life was one continuous struggle for survival. In the process the weak in mind and body lost out to the strong and the resourceful. For generation after generation, through four thousand years or more, this weeding out of the unfit went on […] The Malays, whose own hereditary and environmental influence had been so debilitating, could do nothing but retreat before the onslaught of the Chinese immigrants.

Indignation was my first reaction, obviously. But as I kept reading, I couldn’t deny another feeling that began to rear its head: guilt. For when it came to wealth and financial acumen at least, it became all too clear: my family—at least my mother’s side, whom I spent the most time with—were textbook examples of Chinese economic prowess.

Growing up, money was no object when it came to anything. Education. Shopping. Vacations. Housing. We maintained residences in three different countries. We stayed at luxury hotels and ate at the finest restaurants when we travelled. The adults in my family wore designer clothes as a matter of course. The cost of private schooling for us children wasn’t given a second thought. When Kevin Kwan’s Crazy Rich Asians was published, my childhood best friend called to tell me, jokingly, that someone had written a book about my family.

Our extravagant lifestyle had been made possible by my maternal grandfather’s extraordinary rags-to-riches financial success. As a child, he peddled eggs and homemade cakes to supplement his father’s journalist income. After the Japanese Occupation, he left Medan on a ship, his money hidden away in the shoes he was wearing, to seek his fortune in Singapore. There, he found a clerical position in a Dutch trading firm and worked his way up to become head of the sugar-trading department, before being recruited by a Chinese-Malaysian-owned commodity trading company as a top executive. Eventually, he would be chosen by the Chinese-Indonesian tycoon Sudono Salim (a.k.a. Liem Sioe Liong) to co-found and help run Indonesia’s first flour mill—an appointment that was key in making him wealthy beyond his wildest childhood dreams. And yet, my grandfather’s wealth turned him and us, his descendants, into prime examples of ostentatiously glitzy Chinese-Indonesian villainy. I remember a story that was often circulated around the family dining table—how my grandfather had bought an expensive wedding gown for one of his daughters in Europe during a business trip, then purchased a first-class seat for the dress on the flight home so it wouldn’t get crushed.

By our conspicuously wealthy lifestyle, my family was guilty of reinforcing a stereotype for which others had to bear the consequences. The ethnic Chinese in Indonesia didn’t deserve to be hated. But what about my family? What about me? Hadn’t monstrous wealth turned us into the monsters that Chinese-Indonesians were accused of being? This uncomfortable fact continued to sit in my stomach long after I finished my dissertation, despite my occasional attempts to digest it. For the most part, I tried not to think about it. I didn’t have to at that stage in my life. I got engaged to a fellow graduate student—an American. We found jobs in Atlanta, Georgia, got married, then moved to Australia. For various reasons, I had already been trying to gain financial independence from my family since the start of graduate school. Being married and living far away made the illusion of self-sufficiency easier to maintain. But who was I kidding? Where had the money come from to fund my schooling, my clothes, my food, my life?

Always be grateful for the circumstances you were born in, Kung Kung had often told me when I was small. I had so little as a child. I had to work for all this.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

It was four years after completing my dissertation when I began to revisit the apparent contradiction between my family’s situation and the systemic discrimination faced by Indonesia’s Chinese. After a demoralizing stint working as a fixed-term lecturer at the University of Newcastle in Australia, I decided to leave academia for good. I started writing a new novel, even though my first one had yet to find a publisher. I’d tapped into the Singaporean side of my identity for the first novel, but I felt compelled to set this new one in the wealthy Chinese-Indonesian community, even though (or perhaps because) the subject matter was so close to my heart.

Gritting my teeth, I got out my spade. And as I started writing my manuscript, I began reading again—this time, unearthing information that I had missed or wasn’t available in my graduate student days. Jemma Purdey’s Anti-Chinese Violence in Indonesia, 1966-1999 was especially useful to me, the information in which I corroborated with my grandfather’s self-published memoir, written with the help of a ghost writer and printed the year after I’d finished my dissertation. Prior to that point, I’d believed that my maternal grandfather’s financial success had been due entirely to a combination of hard work and good fortune; for that was what my grandfather and entire family believed too. Now, I learned that something else—or more ominous still, someone else—had played a part.

Even as Suharto had implemented racist measures against the Chinese, he had cherry-picked a small handful of ethnic Chinese businessmen to build the nation’s economy, utilizing their capital, networks, and expertise, much as the Dutch colonial government had once done. But even as this elite coterie was made useful, their immense wealth was held up to reinforce stereotypes about the Chinese as disproportionately and excessively rich. Perhaps the most infamous of this group was Liem Sioe Liong—the man whom Suharto had picked to build Indonesia’s first flour mill, and who in turn had picked my grandfather for the position from which most of my family’s prosperity would flow. (I am sure it was at an official ceremony related to the flour mill’s inauguration that the photo of Suharto and my grandfather was snapped.) The massive wealth of a few and the discrimination and violence suffered by the many, it turned out, were two sides of the same coin—the former used as kindling to fan the flames of the latter. Or to put it another way, a few weeds were allowed to flourish in order to keep the rest in check. Add to this, the fact that the Suharto regime excluded ethnic Chinese from participation in politics, the military, and civil service. Professional opportunities for all ethnic Chinese became limited, fuelling perceptions of them as a race of traders and entrepreneurs.

This new knowledge formed the intellectual and emotional scaffolding for my novel, Under Your Wings, which was released in the US and the UK as The Majesties. On one level, I wanted to write a story about family secrecy and obligations. On another, I wanted to critique the social and political circumstances that had molded the wealthy Chinese into what they had become—and what they had no choice but to become in order to thrive. Mahathir had regarded the Chinese as products of evolution. In the case of Indonesia, perhaps a version of that was true, insofar as the Suharto regime had engaged in artificial selection to create a despicable Chinese “type.” With this on the brain, I wove elements of genetic engineering into my novel—a biologically modified fungus used to control the movements of designer insect accessories; the monarch butterflies bred by Nature to migrate up and down North America’s Pacific coast. I created monstrous characters—like the monster of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, not begotten monstrous, but made so by circumstances, forced to act in certain ways for the sake of self-preservation. (I hadn’t come across the work of the Chinese-Indonesian historian Ong Hok Ham at the time, but years later I would learn he had made similar observations about the fashioning of the ethnic Chinese into an “economic animal.”) I was careful to make the systemic discrimination endured by the bulk of Indonesia’s Chinese a prominent feature of the novel, fearful that a cast of rich Chinese-Indonesian characters would be taken by Western readers as representative of Chinese-Indonesians and, against my intentions, spread the stereotype worldwide.

The novel eventually got published. In the lead-up to the release of the novel’s US edition, I was invited, as writers are often are, to author articles and essays that would help promote the novel. One editor suggested that I compose a list of books around the theme of “eating the rich”—where readers have the satisfaction of seeing rich people destroyed. I asked my book’s publicist to help me come up with another idea. The reason I gave for my discomfort was that, in the context of Indonesia, and thus my novel, Chinese wealth was actually symptomatic of the greater oppression suffered by the Chinese. Therefore, I felt that writing such a list might encourage people to oversimplify the issue when it came to reading my own book.

The other reason, which I did not give, but which was equally true, was that my own family was rich and I felt hesitant exhorting readers to eat them.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

When my Kung Kung passed away last year, nothing could have prepared me for the amount of tribute he would receive upon his death. The wake and funeral were held in Singapore, which was his primary country of residence in his final years. My family spared no expense. For the wake, my mother ordered the garden draped in a massive tent and hired industrial air-conditioners so that guests would be as comfortable as possible. They engaged a luxury hotel to do the catering and ordered crates and crates of good wine. We all knew my grandfather would have wanted to be paid this sort of lavish respect. Eerily, I was put in charge of creating the photo slideshow that would bear testament to his life, from childhood to old age—just like my character, Estella, who is put in charge of a photo slideshow for her grandfather’s birthday banquet, where she poisons everyone in attendance.

The flower arrangements that came in a steady stream were enormous and populated with expensive North American and European blooms. All sorts of people were in attendance: relatives ranging from close to distant; old friends; former business associates from all stages of his career. Many flew in from other countries. A pale, drawn stranger came up to me and shook my hand. He had worked with my grandfather a long, long time ago, he said, and had come from Australia solely for the funeral. There were several businessmen who had flown in from Japan. A few prominent members of the Chinese-Indonesian business elite were there too, staying for hours, coming back for the second day, and even the third—their presence a sign of the utmost respect for my grandfather, who had often self-effacingly called himself “a small fry compared to such big fish.”

I felt so proud of him. And also, guilty of feeling proud. And also, angry at my guilt for feeling proud.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

I’ve taken out the photo of Kung Kung and me again. And the other photo too. I am doing so to write this essay. I stare at me and Kung Kung, Kung Kung and Suharto. It feels like the blood running through my veins has stopped. It is undeniable: this evidence that I am a monster, descended from a monster, fashioned to be so by his patron-oppressor. I will my heart to start beating again. I place my fiendish and ungrateful hands on the keyboard and begin to type.