In their new poetry collections, Chen Chen and Eunsong Kim offer up new possibilities for kinship and survival.

February 12, 2018

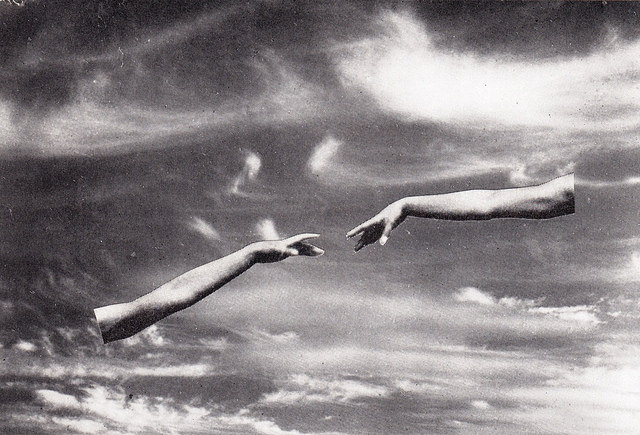

Two years ago I spent Christmas in the hospital. Every day, my friends drove in from the city to visit. They brought Uniqlo underwear and turtlenecks. Poetry. Vogue magazine. We’d sit in the dining room and hold hands. I was lucky to receive visits, to bask in kinship forged by choice rather than by blood or obligation. Even now I am amazed by the simple existence of this memory—however brief our visiting time we could be together. “Is she your mother?” a nurse later asked me. “No, they’re my friend,” I said, like someone falling in love at first sight.

Ours of course was of our making. Living with people is political. Making collective living possible is political. When I say we take care of each other this means following through on gestures, whether it’s cooking a household meal for folks feeling down, fixing the pesky bathroom door, having ongoing conversations about racial capitalism and ableism, or addressing points of conflict. That this intimacy can be sustained is because we are committed to sharing the emotional work of care.

A chosen family requires a language for forgiveness as much as one of resistance. In many cases, the relationships I’ve forged with my friends provide the kinds of nurturing our families at birth did not provide. Many of us came from homes that informed our cultural upbringing as first generation people of color but could not comprehend the parts of us that are queer, struggle with mental illness, or lead non-traditional lives. We did not totally repudiate the idea of family. Rather, we had to unlearn what we had been taught about family in order to model intimacy as a source of possibility in our everyday lives.

When I Grow Up I Want to be a List of Further Possibilities is a book that models this intimacy by betraying the family in an obvious sense: Chen Chen’s parents are imperfect and cruel. They make mistakes. They get sick. They are disappointed in their son, who in turn internalizes the disappointment of having failed as a son. On the first page, Chen declares, “I am not the heterosexual neat freak my mother raised me to be,” followed by the insistence: “I am a gay sipper.” His observation is flippant and funny but its tone emphasizes the emotional distance separating parental expectation from personal actualization.

Can you be both a good Asian son and queer? How will you make space for your diasporic angst and your desire to be loved? In a way, Chen’s refusal to answer becomes the groundwork for writing the poetry of potential. Potential is a leverage for imagining the possibilities that reality has withheld. In “Race to the Tree,” a three-part poem, Chen recalls running away from home in the middle of the night, an incident which involves a police search for him and ends with a broken foot when he slips, accidentally, from the tree. With each section, underlying motives and details unveil a portrait of a teenager alternately upset and amazed by the revelation that he just wants to be touched. Thinking:

how it would taste

to kiss, to be kissed, oh

moon, for a long time, for the time,

to be k-i-s-s-i-n-g in this

or any tree . . .

Chen takes comfort in his longing for a boy’s kiss, that tenderness lingering more fondly than the immediate family drama being staged: Chen’s mother slapping him because he has told her he is gay, him hitting her in reply, and his father “holding us apart / like the world’s saddest referee.” A few pages later, in a poem titled “First Light,” the more painful memories of the incident are recalled. Here, the intention behind his parents’ words is undoubtedly clear—his mother calls him her dirty, bad son, led astray by Western devils and his father says Get out, never come back.

Leaving is a powerful feeling. It is a release of grief, frustration, uncertainty. It activates the ongoing recognition that growth is a deeply visceral process. Senses acquire the otherworldly dimension of possibility, the fulfillment of prolonged intimacy. To taste the light. To kiss your lover instead of going out. To chase after madness. “Dreaming of one day being as fearless as a mango,” Chen writes in “Self-Portrait as So Much Potential,” even though “I’m no mango or tomato. I’m a rusty yawn in a rumored year. I’m an arctic attic.” On the page, there is something unabashedly exciting about being seen for what you do instead of what you represent.

Despite betraying “home” and “family” Chen remains open to the tenderness of the world. The most coherent moments in his collection are grounded in the shared intimacy of we. “We” is a pronoun that softly lingers, that prolongs and accommodates alternate forms of companionship throughout the book. “In New York we read Darwish, we write broken sonnets finally forgiving / the Broken English of Our Mothers” to “We loved green tea but often had / Orangina instead” to “Are we even built for peace?”

To escape for the pure adventure of it. To be weird, warm, and aimless.

By contrast, Eunsong Kim’s Gospel of Regicide depicts betrayal as it is driven by revenge. Under Kim’s rendering, betrayal is a politic, the mobilized resentment of white supremacy and neoliberalism. Anger is a framework and an agenda. By drawing strength from gendered emotions and forms of labor, the work’s impetus is to identify the tender spaces of radical life that we have learned to disguise out of fear and, alternately, self-preservation.

Such as gossip. In Gospel of Regicide, gossip is both petty and transformative. Passages register the disappointment of a speaker who resents falsely realized communities, who resorts to betrayal as an act of salvation. Kim writes:

traitors come prepared

traitors are more prepared than you are

you are nothing in contrast to the

poetry flooding inside the traitor’s flesh

In my circles, gossip was one of the few ways we could actually engage in critique, despite its petty nature. My friends and I gossiped because we did not know how to challenge without undermining the queer Asian community we had always wanted and believed to have finally found. Bound by solidarity to maintain a certain appeasement, we critiqued outsiders while internally, we practiced a flawed understanding of transformative justice that replicated the problems we swore to betray. What do you do? We witnessed toxic interpersonal relationships strain entire communities and stayed silent, we witnessed times when performative politics exacerbated existing power dynamics and stayed silent.

Amongst ourselves, we gossiped. Designating ourselves as petty relieved us of the social expectation to uphold solidarity, to ask Has there ever been solidarity? It let us say the ugly things we needed to say about people we knew whose infallible politics masked coercive behavior.

Gossip makes room for self-critique in a way blanket solidarity does not. The gossip’s mystique provides it a certain illegibility under capitalism within which bodies accordingly exchange their time and labor for the barest resources of survival. The gossip rejects the idea of working on or off the clock because she is always working. The gossip knows how to leak the scandal waiting to happen, she controls how and when the conversation happens:

so just that we’re clear in this deletion, if we don’t say your

name immediately, we don’t address you immediatelyi will say your name directly at some point before i die

Gossips are neither liked for what they know nor for what they can expose. As Sara Ahmed has written, to name a problem is to become a problem for those who do not want to recognize the reality of the problem. For the traitor, naming is a radical gesture that refuses to remain reasonable. She who catalyzes revolution will be cast as the traitor.

In Kim’s writing, as in Chen’s, the traitor is the one who leaves. The one who says NO and pursues an alternative. Inaction is a worse fate than failure. Though she is “remembered only through their gossip their scorn,” the traitor knows how to spread dissent into the undercurrents of ordinary life. The act of gossiping is a precarious line of work because it is undervalued and feminized.

Kim writes,

i’ve been wanting to write an epic on treachery. The love it requires.

its militancy

…

i want to write an ode to her. And how becoming

her is the only goal in a resurrected life—

and

These are not confessions this is not a confession

They are a collection of revisions upon revisions that roam my

memories which means theyare utter lies and my only foundation

The fulcrum of the traitor’s work is memory. Memory as contractual. Memory as the faulty appendage against the automation of the world-as-is. When theory and politics become complicit in maintaining the status quo of inventory—“gramsci reference check. explanation of hegemony check. the importance of a love triangle check”—betrayal is a final act of love.

How do you be purposeful about who you betray? In their texts, Chen and Kim insist on naming the failures of literary representation. It is not enough to be seen. It is not enough to be loved. Inclusion is a fraught, alienating process. To speak out against respectability politics, neoliberal complacency, or institutional whiteness is an isolating experience. Chen: “I’d like to take the time to acknowledge here the real and brilliant Asian American poet who could have appeared in [The Best American Poetry 2015] instead of the appropriating and exoticizing white American poet who did appear.” Kim: “Imagine my surprise when I’m sitting in an artist lecture by an Asian American artist who at some point says that aesthetics and politics are separate. I write in my notes: Kant lover <3 <3 <3, whatever, you suck die.”

Poetry is the space in which becoming something other can be realized. Like community, poetry is a situation that has to be intentionally built. Sometimes you have to leave before you can begin. My friends and I, as co-conspirators, moved to a new city with this pursuit in mind. Community building is a collective undertaking, its shaping sustains the momentum of our voices in spite of: everything against us. More than survival, I want us to read to one another. I want us to betray the spaces that cannot accommodate us, that were never meant to. In our life, saying no is an act of tenderness.