Haunting a house isn’t as easy as you might think.

May 1, 2023

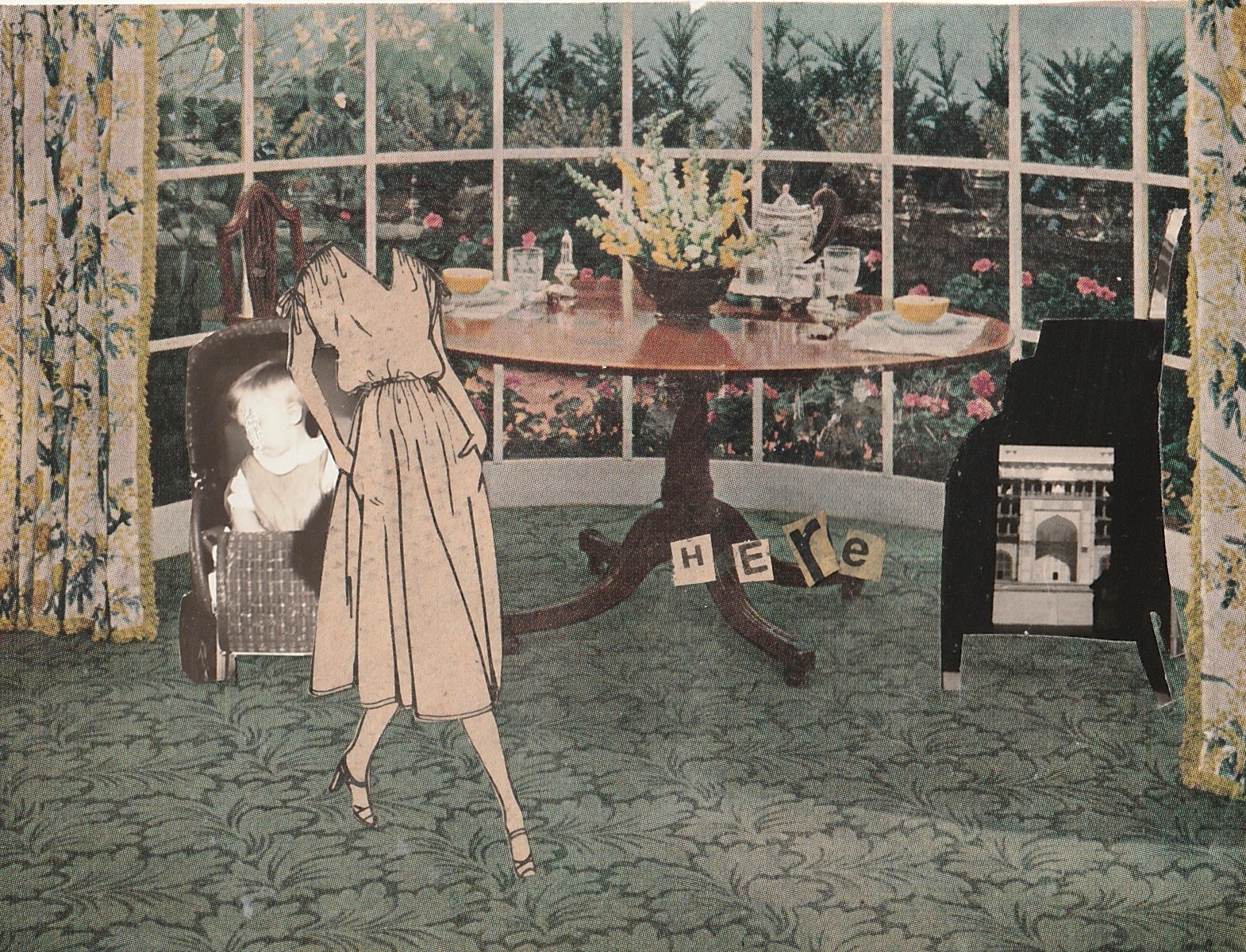

This piece is part of the Love Letters notebook, which features art by Ali El-Chaer.

Despite what you see in the movies, haunting a house isn’t as easy as you might think.

It seemed pretty straightforward. Switch the television on and off. Flicker the lights, scratch at the walls. Murmur his name.

I tried all that, but it was impossible to get his attention. He didn’t appreciate all the work I put in just to get him to notice me. Death was a lot like life in that way.

It’s not like I planned any of this in advance. The last thing I remember was swerving to avoid a teenage cyclist. Then, next thing I knew, I was in this shitty studio apartment, floating several feet off the ground.

I was surprised he still lived here. I hadn’t seen the place in years.

There were perks to being invisible. It was a good chance to snoop. There was something thrilling about peeking into the mundane intimacies of someone else’s life.

I wasn’t a voyeur—it’s not like I spied on him in the shower. There was no point. I already knew his body, its secret lumps and crevices. I could draw his cock from memory.

Instead, I rifled through drawers and examined his bookcase. On the top shelf was a shoebox filled with old photographs. Only one of them was framed, a picture of himself as a baby. Like many white babies, he looked like a hardboiled egg, flesh pale and glossy, hair the soft yellow of an overcooked yolk.

By the time the first week had passed, I had surveyed every corner of the apartment. He remained oblivious to my presence, and I became bored and self-pitying. Petulant.

Notice me. Notice me.

Ghosts can’t control the weather. We can’t conjure up a lightning bolt or a dark and stormy night. That’s just basic meteorology.

We can, however, take advantage of what’s already in the air. And if there’s one thing ghosts know how to do, it’s how to exploit an opportunity. Can you blame us? The afterlife gets boring.

So, I waited until the next thunderstorm. If I couldn’t get him to appreciate me, at least I could force him to pay attention.

I started slowly. A few innocuous thumps beneath the floorboards, subtle enough that he could convince himself it was only his imagination.

Gradually, I got louder. Creaking, scraping, skittering, clattering. Then, once the storm was at its peak— rain lashing down, thunder growling—I thrust open all the windows.

That he couldn’t ignore. I could tell he was scared. His face looked like a burnt-out birthday candle.

It was a long time before he fell asleep.

When morning arrived, I felt as guilty and greasy as a hangover. Scaring him wasn’t as satisfying as I’d hoped.

There was nothing to do but sheepishly tidy up the mess I’d made. I wrung out the curtains and evaporated the water from the floorboards. Then I cleaned the rest of the apartment for good measure.

I liked feeling useful. Afterwards, I wanted to do more. I found subtle ways to make myself indispensable, switching off the lights when he’d fallen asleep on the sofa, making sure the kettle didn’t boil over. He was always losing things, so I’d hunt through the apartment and collect everything he’d misplaced, lay it out for him on the dining table. It was worth it for the way he looked when he rediscovered the things he’d lost. Like a child who still believed in magic.

Many years before, he once told me: It would be so easy to fall in love with you. It was the closest he ever got to saying the real thing.

He probably didn’t even remember saying it. But I couldn’t forget it. I returned to the memory so many times that its edges became rounded and smooth like a river stone.

Sometimes it was unclear who was haunting whom.

He didn’t make a big deal of it, the first time he spoke to me out loud.

“I always wonder whether you’re here,” he said. “Or are you always here? Is that how it works?”

I wanted to say something back, but there weren’t a lot of options for communication as a ghost. It was a lot of banging and stomping. No matter what, you sounded like a sullen teenager.

I knocked a glass of water off the nightstand. It toppled over and rolled under the bed, leaving a damp trail in its wake. I turned on the kitchen faucet, each drip a declaration.

I’m here. I’m here. I’m here.

Eventually, we figured out other ways to communicate. I’d listen to him complain about work and ruffle the curtains sympathetically. He’d make a joke and, in lieu of laughing, I’d rattle the silverware in the kitchen drawers.

“I’m thinking about painting the apartment,” he said. “Is that something you can help me with?”

I brightened the lights. That meant yes.

He brought home three buckets of paint and let me choose which color would go in the bedroom. I picked a quiet green that looked like the underside of a new leaf.

I dragged all the furniture to the center of the room and draped a cloth over it. He taped up the corners and the baseboard molding. We painted the walls together, me hovering a brush up to the tricky bits by the ceiling. There were a few spots that I missed, but you could hardly tell. I liked it anyway. I’d made my mark on the place.

He still didn’t know who I was.

There was an alarming number of people he thought could be haunting him. He lobbed guesses like tennis balls: “Pamela Einhorn? Vinny Kim?” Most of the names I didn’t recognize. I wondered who they were to him.

One day he would say my name. Or maybe he never would. Maybe it didn’t matter. We still belonged to each other.