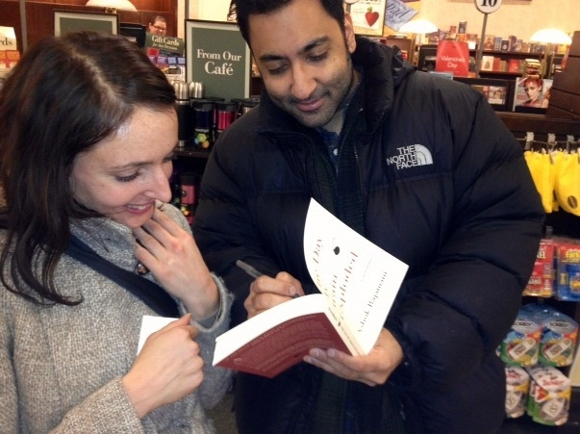

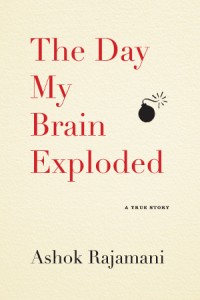

Kyla Cheung talks to Ashok Rajamani about his uniquely humor-filled memoir recovering from an aneurysm at the age of 25.

March 7, 2013

Excerpt from Ashok Rajamani’s The Day My Brain Exploded: A True Story

When the pain grew too intense, Ashok-as-Christ emerged. When I watched my family members—all sitting in chairs, their faces wearing looks of deep agony and despair—I realized I had to save them. So began my romantic affair with my corporeal self. I would rant daily, "I'm the Body of Love, I'm the Body of Love," as my family looked on in mute, helpless horror. In those moments, I inhaled the world's suffering. All of humanity's dreams, hopes, fantasies, and nightmares lay inside of me, and I never let the doctors and nurses forget it. Whenever they performed their routine tasks, I said solemnly, "Go ahead. My body is ready for you." My mind whirled through erotic nightmares and dreamscapes as well, involving different genders, fluids, and bleeding and sucking. I recall one hallucination vividly: in my mind, the hospital had a secret orange room, a room of depravity, a room of liberation. It was packed full of women and men of different colors...I remember seeing a gorgeous Indian girl and sucking her nipples till she ripped them off herself out of pain. And when the Latino started exploding in my mouth, his juice wasn’t white, but red. It was blood. I was so turned on, and the more aroused I became, the bloodier the room became.

–

OC: Your memoir opens with a quote from the poet Rabindranath Tagore, a quote from Lewis Carroll, as well as a quote from Charo, the Spanish 1970s comedienne. What did you mean by including all three? What artists inspire you?

AR: Tagore, Carroll, and Charo all inspire me. If we were to ask if I existed in the high-brow world or the low-brow world, then I would say, without question—both. I dig Dolly Parton and Frida Kahlo. I like to call my book the anti-Oprah book. Yes, it is the story of surviving a tragedy, lending itself to mawkishness and over-the-top sentimentality. But, this is not that type of book. My book revels in comedy, tragedy, bawdiness, and flat-out vulgarity, and redemption all at once. But it does not implode into sentimentality, that’s for sure. As for which artists and people who inspire me… there are too many to name. But here are just a few off the top of my head: Frida Kahlo, Gautama Buddha, Malcolm X, Madonna, Swami Vivekananda, and of course Jem (the cartoon character).

“New York City reminds me of a friend that had a miscarriage.”

OC: Your book is funny considering the sobering material. Was that something that surprised you?

AR: My book is written with comedy because that reflects who I am. Before my hemorrhage, I’d always found humor in even the darkest of circumstances. Luckily, I have retained that baseline personality trait even after the brain explosion. I’m convinced that humor saved my sanity.

OC: What are your thoughts on how your many identities—as a traumatic brain injury survivor, an Indian-American and a person of color, interact with one another? How did these affect your approach to writing?

AR: Being brown is visible, but being brain-damaged isn’t. Sadly, both issues are not discussed enough in pop culture. The circumstances of racism toward Indian-Americans are never fully dealt with in literature, and brain damage is not historically a major-league subject in books. I’m glad to bring out these issues. In my acknowledgements, I give props to little brown kids in America’s Heartland and to brain-damaged warriors as well. I hope I can represent them well, and by publicizing my life, I hope I can publicize theirs.

OC: One of the funniest parts of the book is when you, as a 5th grader, get into a shouting match with your classmates after you show-and-tell a bronze statue of Krishna with them yelling “Jesus” and you yelling “Krishna.” It’s a comedic and also insightful moment of how early on Americans recognize and participate in identity conflict.

AR: I don’t think kids are inherently racist. They fought with me not because they hate brown skin, but because they are curious. Once teen-hood begins, the racism kicks in.

OC: Your relationship with your family members plays a very present role in the memoir. The letters your mother wrote are some of the most touching moments in the book. She writes to you as you lay in the hospital bed and pleads with God, “Why did it all have to happen?” Did your perspective change as you wrote the memoir and included your family’s voices? How has your family reacted to the book?

AR: When I wrote the book, I realized my family never gave up, even when they could have. My mother’s letters were the most challenging to include. They not only voiced her love and support for her child, but also her fears, and of course, her pain. I gave my folks advanced copies of the book for Christmas. To my surprise, they loved it right away! I was shocked, because South Indian Brahmin families are usually the first to disavow sharing private matters.

OC: You mention in your memoir how you witnessed a marked change how you were treated after 9/11, recounting how your father’s close friend, a Sikh man, was killed in a hate crime. You still live in the city and have often, in the case of your seizures, have been on the receiving end of the kindness of New Yorkers. What is your relationship to the city now? Has it changed?

AR: New York City reminds of a friend I knew that had a miscarriage. She was freaking out, depressed, sad, and angry for the months before-and-after her pregnancy. After many, many months she returned to normal and life went on. With 9/11, New York City suffered its own miscarriage, or more fittingly, a brain hemorrhage, and survived it. It took a while to move on, and even though it has some scars, it has moved on. Yes, it was a tough time to be a brown male from 2001 to 2002, but New York soon came back to the city I remembered—the one without xenophobia and fear of brown men.

____

Ashok Rajamani tours the East Coast:

March 28—MAPLEWOOD, NJ—[Words], 7:30pm

April 2—NEW YORK CITY—Barnes & Noble, 7:00pm **Joint signing with Domenica Ruta, With or Without You: A Memoir.