An Introduction

July 26, 2021

Editor’s Note: The following introduction is part of a notebook Queer Time, co-edited by Ta-wei Chi and Ariel Chu, which gathers contemporary queer Taiwanese literature in translation. To read the full Queer Time collection, visit its home here.

Queer time challenges normative history, bringing to light the fragmented narratives, asynchronous lifestyles, and suppressed voices of marginalized subjects. In Taiwan, time has never been straight. Navigating successive colonizing forces, polyphonic language communities, and modern geopolitical tensions, Taiwan has enjoyed a legacy of non-heteronormative literature at least from the 1960s up to the present day, as evidenced by such story collections as Angelwings: Contemporary Queer Fiction from Taiwan (ed. Fran Martin, 2003) and Queer Taiwanese Literature: A Reader (ed. Howard Chiang, 2021). This notebook is both a continuation of and a departure from Taiwan’s legacy of queer and non-heteronormative literature, also known as tongzhi wenxue in many Sinophone countries. The pieces in this collection highlight queer subjects living in a uniquely “queer” nation: not merely for its legalization of same-sex marriage in 2019, but also for its contested sovereignty, its competing “official” histories, and its fraught search for a cohesive identity.

The pieces in this notebook challenge the notion of a “straight timeline,” resulting in narratives that are queer in both form and content. Leah Yang (楊隸亞)’s “Nobi Nobita’s Body” (trans. Jenna Tang) uses a series of flashbacks to trace the protagonist’s relationship with other bodies and her own. Chen Bo-ching (陳栢青)’s “Boy God” (trans. Kevin Wang) follows two narrative threads—a drug deal presumably happening in the past, a secretive meeting between two men in the present—to disorienting, dreamlike effect. Yang Shuang-zi (楊双子)’s “Seasons of Bloom” (trans. Lin King) follows a time-traveling young adult as she navigates her feelings for another woman in Japan-occupied Taiwan. And Yi-Hang Ma (馬翊航)’s “A Room by the Sea” and “Sissy-Gun” (trans. Siyü Chen) explore queer Indigenous youthhood through retrospective narratives. Through sense impressions, cinematic references, and defamiliarization of local culture, the narrator pieces together a life that deviates from masculinity.

These pieces excavate possibilities out of Taiwan’s past and present, positing queer futures that destabilize entrenched norms. Hsin-Hui Lin (林新惠)’s “Peeling Off” (trans. Ye Odelia Lu) takes the capitalist present of Taipei to the extreme, positing a world in which people’s very bodies are eroded by consumer culture, loneliness, and corporate disillusionment. Petit (夏慕聰)’s “Military Dog” (trans. Yahia Zhengtang Ma) explores a local BDSM subculture shared by “human puppies” and their “Masters,” subverting the normative culture of compulsory military service. And Eno Chen (陳佩甄)’s “Queering History, Archiving the Future” (trans. Jeremy Tiang) posits that in reconstructing a history for Taiwan’s senior lesbians, local scholars have discovered even more possibilities for queer community-building. This notion is taken even further by Grandma’s Girlfriends, an oral history project conducted by the historic Taiwan Tongzhi Hotline Association. An excerpt from this “public history” introduces the “tomboy” Huang Hsiao-Ning and the radical futures he explored as Taiwan’s “dashing female Elvis.”

Of course, queer time works in tandem with queer space: liminal territories that exist at the margins of acceptability and visibility. In Hikaru Lee (李屏瑤)’s “Centennial Harmony, Centennial Lilies” (trans. Kittie Yang), a dating app becomes a channel between the living and the dead. Jade Huang (黃岡)’s three poems (trans. Louie Zhang, Riley Tsang, and Sean Y. Li) leap between a gym, a fishing village, and a foggy bathroom, finding tiny spaces where queer intimacy can flourish. david hsu-tai lo (羅煦泰)’s “moonlit” evokes cinema, history, and memory out of everyday objects and the absences they leave in their wake. Finally, a virtual three-way interview between Ta-wei Chi (紀大偉), Hsin-Hui Lin, and Ariel Chu (朱詠慈) strives to compress the distance between Taiwan and the United States, placing different generations of writers into conversation about the COVID crisis, compulsory visualization, and what it means for queer Taiwanese literature to be “speculative.”

Amidst a backdrop of geopolitical uncertainty, queer stories serve as assertions of self and community, narratives that refuse to be assimilated into dominant political frameworks. We hope that this collection of contemporary Taiwanese writing not only serves as a marker of queer time and space, but also inspires readers to seek and create alternate timelines of their own.

—Ta-wei Chi and Ariel Chu, Guest Editors

Taipei, Taiwan

July 2021

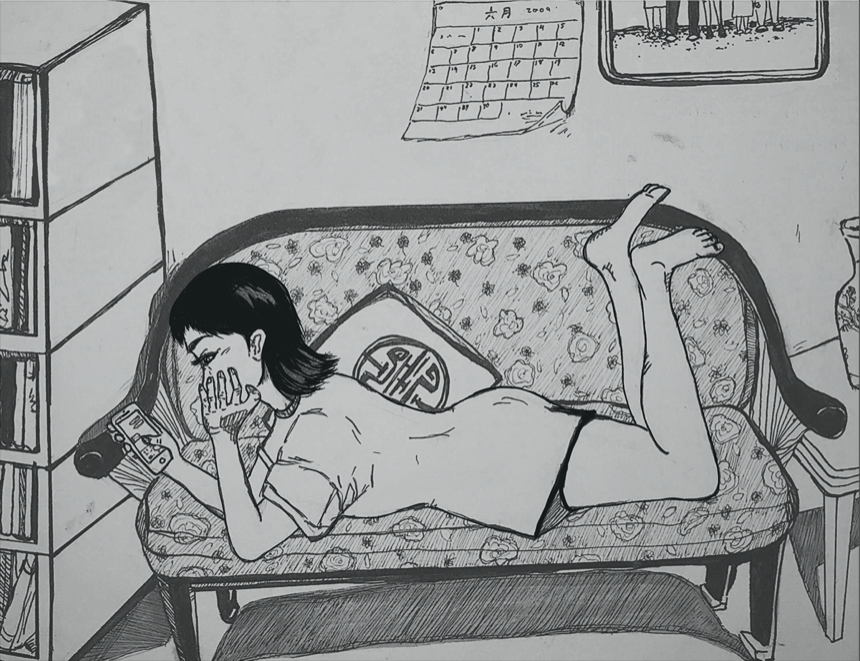

Notebook illustrations by Kira Wei-Hsin Jacobson