An interview with journalist Hsiao-Hung Pai, whose book Scattered Sand tells the stories of Chinese migrant workers—direct from their mouths.

January 9, 2013

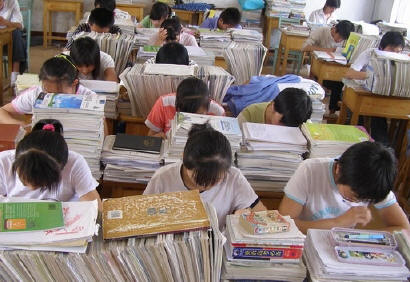

Despite the whirlwind of discussions around China’s economic boom, the struggles of its workers are, remarkably, rarely mentioned. Even more absent: the approximately 200 million migrant workers in China who leave their homes for months or years at a time to seek jobs in cities and industrial zones.

Hsiao-Hung Pai, a UK-based Taiwanese journalist known for her intrepid reporting and depth of research, cuts to the heart of the issue and interviews the migrant workers themselves. Her book Scattered Sand (Verso Books, October 2012) takes us from brick kilns outside Tianjin, a metropolis in northern China, to the factories of Guangdong, to the Fujianese communities in the United Kingdom. Though there have been academic studies and a few documentary films about the phenomenon, Pai offers us a chance to hear a wide range of migrant workers’ voices, retelling their stories in a frank and straightforward tone.

Pai is shouldered with the dual burdens of introduction and context: The situation of migrant workers cannot be understood without also understanding the economic reforms of the 1980s, the hukou system, or the fragility of agrarian lifestyle. Pai folds these strands into her narrative. Coupled with interviews and firsthand narrative, we are offered a portrait of a richer and more human China than the one the media often chooses to portray.

Everywhere Pai travels, she encounters people eager (and, in fact, often desperate) to tell their stories: They introduce their friends, take her around their workplaces, and share personal details, all the while hoping their stories will reach the ears of someone who might be able to help. One senses that for these workers, Pai is a rare listener, a welcome outsider to a world driven deaf by profit.

Ryan Wong: You wrote Scattered Sand for an audience that might be unfamiliar with the phenomenon of migrant labor in China. How would you like this work to raise awareness among consumers in the US and UK?

Hsiao-Hung Pai: Although consumers and readers in the UK and US might be unfamiliar with migration in China (and also Chinese migration to the UK and US), the phenomenon is linked with their everyday life. China produces a third of the world’s manufacturing products, and 40 percent of China’s migrant workforce is toiling in manufacturing sweatshops, producing products such as Apple iPads, iPhones, Burberry handbags, Christmas toys and designer shoes that consumers in the west cannot seem to live without. While consumers in the UK and US benefit from the convenience and lifestyle these products bring, migrant workers in China are enduring half the urban wage, appalling working conditions and the absence of basic rights. It is these conditions that have driven many workers to despair—thus the tragic suicides in Foxconn’s factories. Consumers in the west are becoming more aware of these conditions as the suicides have led them to read about [the] workers’ situation in Guangdong at least. But the reality is much wider than what happens at Foxconn. Scattered Sand demonstrates that migrant workers are being exploited across industries, all over China. Consumers need to understand the supply chain and know where their products come from and at what human cost. The least the consumers can do is to begin to question the practices of multinational [corporations] and put pressure on changing them.

As you describe the process of interviewing workers, it seems the majority were desperate to share their stories, even of grueling hardships. How did you select which stories to include in the book? How did the workers you interviewed want their stories to affect your audience?

Yes, the majority of people I met were approachable and eager to tell their stories. It was obvious that there was so much anger and frustration and many migrant workers simply were delighted that someone wanted to listen to them. They wanted the world to know about their reality. One man who really moved me was a migrant jobseeker in Shenyang, surnamed Ren. He had written many essays and poems during his time in the cities, and was so eager to show them to me. He wanted his writings to be published, so that the people in the outside world can get to hear about his situation. He wrote about working as a builder in Shenyang, and about his loneliness and isolation living in the city. I quoted a piece of his writing in Scattered Sand, where he described his deep sense of guilt for his parents.

Some workers were very keen to share stories, as they hoped that the publication of their stories will help highlight their problems, such as wage arrears and non-payment of wages. One very saddening example was a group of migrant miners in Urumqi, Xinjiang, who had not been paid for more than two years and couldn’t return home for that length of time. This shows how desperate these workers are—having to put their slim hope on someone living outside of China to expose wrongdoing of the companies, on their behalf.

I think the stories simply fall into their place according to the geographical structure of the book. By and large, I had focused on three main groups of people to interview: those who have migrated from the countryside to the cities within China; those who have migrated abroad; and the migrant workers in Britain who have achieved the dream of improving the lives of their families. The aim is to get a glimpse at the material circumstances that have motivated people to leave home and migrate, either into the cities or abroad, and to understand what has kept this migration going despite the difficulties in reaching their destination countries and the hardship that they will surely face when they arrive.

A striking seventy percent of the factory workforce in the Pearl River Delta is comprised of dagongmei (unmarried working girls). How do you see this influx of women into factory jobs shaping the gender dynamics of this next generation? How did the young women you talked to see their jobs in relation to more traditional female roles?

Many of the dagongmei see settling in the cities as a long-term goal and they aspire to urban life. Their aspirations also grow as a result of their time spent in the cities. Some of them, particularly those who have higher education and occupational skills than their parents, are beginning to break away from their rural origin and do not see marriage and the traditional female reproduction role as their aim in life. Some young women have expressed their wish to set up their own business in the cities eventually.

The last chapter, on Fujianese emigration, highlights the diaspora created by the desire to escape poverty. But, as exemplified by the Morecambe Bay tragedy, migrant workers are as much at risk in the UK as in China. Do you foresee Chinese migrant workers’ rights in the UK advancing before those in China? How are the two struggles related?

Most people, before they set out on their journey to Britain, would have heard about the possible circumstances in which they might find themselves when they arrive. But they see the risks as worth taking because wages here [in the UK] are many times higher than in China. If a migrant is able to stay in full-time employment for three to four years in Britain, it’s likely that s/he will be able to pay off the loans [incurred from the journey] after that length of time. With that in mind, a migrant knows that s/he would be able to earn [enough] to build a house, save up for [their] children’s future and improve life at home generally, as long as they come to work in Britain. Conditions are hard, but the rewards are worth it, in their eyes.

Yes, there are comparisons to make between their struggle in the UK and in China. In both, migrant workers are a ghost population producing for social wealth while not [being] given proper status and rights. In the UK, there has been an attempt to demand rights and gain status for the undocumented (e.g. the “Strangers into Citizens” campaign that involved wide sections of British society). There have been efforts made to broaden that discourse. But in China, society in general is still reluctant to include migrants as part of the working class. Prejudices run deep, and [the] media are by and large hostile to the migrants’ cause for equality.

You relate workers’ stories of employer abuse, separation from families, and homesickness. But there are also stories of persistence and resilience, as in your friend Mr. Qi’s dogged attempt to recoup unpaid factory wages. After writing this book, are you optimistic for the future of migrant workers in China?

All throughout my research in China, I’d felt quite pessimistic, having seen the institutional obstacles that migrant workers are facing. There may be individual attempts to seek justice, and there were the spontaneous strikes in summer 2010 which offered some hope for change. But overall, workers are fighting their battles alone and it’s a depressing sight. Unless they have the right to freely associate and organize themselves as a workforce, individual attempts to challenge injustices will remain sporadic and temporary.