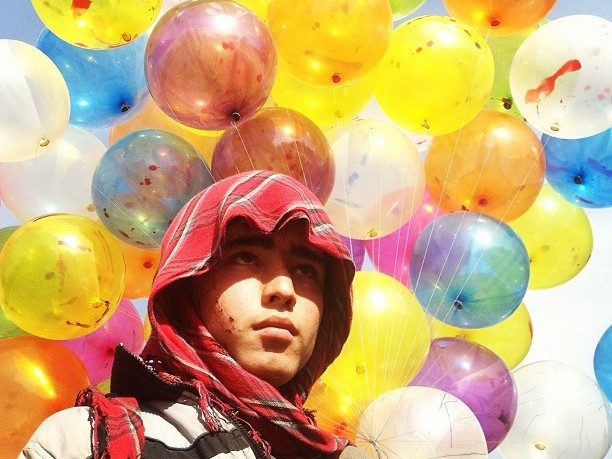

The world forgets us. The world does not see us. The world turns its back on us, Afghans.

November 2, 2021

Editors’ Note: In her introduction to the Fall 2011 issue of the Asian American Literary Review, coeditor Rajini Srikanth writes of how quickly we can forget our communities’ milestone moments of political awakening. Commemorating the 10th anniversary of September 11, that issue of AALR, edited by Srikanth and Parag Rajendra Khandhar, attempted to fill in the gaps of official acts of mourning. The testimony, dialogue, essays, and art brought alive the struggles and resistance of Muslim, SWANA, and South Asian communities in the days, months, and years after September 11.

We asked a number of contributors to the Fall 2011 issue of AALR to return to their writing and speak into the space of the past 10 years. The following essay by Zohra Saed is part of that series within the Living in Echo notebook.

Ten years ago, for the Asian American Literary Review, I wrote about my Afghan American friend, Farhad Ahad, who had gone back to Afghanistan in 2002 to put his engineering degree to work and to be part of reconstruction. A mass of Afghan diaspora exiles were going back to Afghanistan then and the young generation were being referred to as “the bridge generation.” Sadly, most of the bridge became tangled in the corruption that plagued Afghanistan. Back in 2011, I wanted to remember the optimism and the innocence of my friend Farhad who had gone back and was killed in an uninvestigated and suspicious plane crash of dignitaries and engineers investigating a copper mine near the border with Pakistan. The Cessna plane had crashed off the coast of Karachi. Farhad was Deputy Minister of Mines and Natural Resources. He was fresh out of graduate school. His laptop was sent back to his sister completely cleared of all information. She wept so openly in front of me after the funeral. “His diary, his photos, everything was erased!” Only a handful of photos of Farhad on a plane, and a VHS video tape of him remain. In the video he smiles and waves at the camera, perpetually young, and perpetually hopeful. It was filmed by the Minister of Natural Resources who also died in the plane crash. Farhad ‘s body was sent back to Queens and he was buried in Long Island with $50 in his bank account and student loans remaining from his graduate studies. For me, the dream of return ended with the death of Farhad. I never quite got over the grief that his return cost his sisters and his fiancé. But young ambitious and underprepared Afghan Americans migrated for jobs in Afghanistan creating an elite group of Afghans who admitted to barely touching their feet on Afghan soil, since they traveled from car to office without once being on the streets of Afghanistan. It was not the elitism that Farhad had experienced and his death meant nothing to those he served. Now 20 years and a few days away from the first bombings of Afghanistan, there is another mass migration of Afghans, this time coming to the United States as refugees, again.

It is August, and I am in New Jersey. It is early Sunday morning, and I am in the backyard on a Zoom call with Afghans and Afghan allies from Europe, Australia, the East and West Coasts of the United States. We are thinking of one thing: Has the Taliban won? What will happen now? What will happen to our friends? We need to understand this together. Whether we know each other or not, we are Afghan. Even if our links are strained, even if our language is threadbare, choppy, we feel connected to each other. This comforts us and we need each other to talk through this. To ask together, what will happen to our families, friends, and to the people in Afghanistan?

While we are figuring out how we can help Afghans, we hear that Ashraf Ghani has fled Afghanistan and abandoned the people. Along with him, the Afghan national government starts leaving as well on evacuation planes. These intellectuals and politicians have many names: “Whiskey Boys,” “Parachute Afghans”—they are now mostly known as traitors and cowards. We, artists, writers, scholars, and activists, we try to step in and fill the bureaucratic gaps. We try to respond to the help messages we get as texts and email.

The Afghan diaspora Group Chats and social media are divided. Do we scream in anger about the privilege of those in government abandoning the people to the Taliban? Or do we feel some kind of sympathy for them as their corrupt parents and cousins are outed in the news? I have no sympathy. Others do. There are angry words. Fights. Arguments. Has the Taliban changed? Is the United States worse or the Taliban worse? Are you colonized for hating the Taliban?

I hate the Taliban unapologetically. I am part of the Uzbek minority. My great grandparents and grandparents, as children, fled to Afghanistan as refugees from newly formed Soviet Uzbekistan and were settled into Kabul, Mazar i Sharif, Maimana, and in the case of my family of dentists, in Jalalabad. But there have always been indigenous Uzbek and Turkmen who are the carpet weavers, the players of Buzkashi, the farmers who produced karakul wool for the famous karakuli Afghan hats. These things make up the fabric of Afghan culture yet, Uzbeks, Turkmens, like Hazara, like Afghan Sikhs and Hindus, are looked at as perpetual foreigners in their own land. We do not have the luxury to wonder if the Taliban have changed because we know they are coming for us.

Uzbeks, Turkmen, Kyrgyz are Turkic minorities in Afghanistan and make up 10 to 12 percent of the population. Since the 1990s they have fought against the Taliban and in 2001 imprisoned, hanged Taliban fighters under the leadership of Abdul Rashid Dostum. The revenge attacks in Sheberghan, the burning of the park there and in Kunduz, is a violent sign that the Taliban remembers. Now Dostum is safe because he can afford to be, so it is the ordinary Uzbek people who suffer the venom of the Taliban. Uzbeks are a minority overlooked in evacuations. There are few government connections for Uzbeks, so they are left behind from airlifts. Only a handful have made it out on evacuation flights.

Arguments are quickly typed out on Twitter. Bridges burnt and a big good riddance to anyone who supports a terror regime. Yes we can be both against drone bombings and against the Taliban. Yes there is an ethnic hierarchy in Afghanistan that needs to be addressed or else we will forever be pitted against each other by foreign intervention, as in the entire modern history of Afghanistan. But who is ready to talk about that history in the midst of upheaval? Who is ready to question Afghan unity at a time like this? But if we can’t talk about it now, when will we talk about these aches? When will we address these unheard, unrecorded histories that were whited out in favor of an overly optimistic image of Afghanistan that never existed?

Regular people in the provinces start their resistance. They shake the narrative that Afghans from the provinces were pro-Taliban. They wave a black, red, and green flag to challenge the white flag of the Taliban. Women in their burqas wave flags. A black, red, green flag that is the length of several blocks is paraded in the city. Young people are shot for waving flags. Women start protesting next. Kabul, Herat, Mazar i Sharif, Kandahar, Jalalabad… they push through the Taliban soldiers and demand rights. There is a call to find refuge in Panjsher and to join the resistance. Mujahideen images were revived and revamped. But these, too, all fall away after the massacres in Panjsher, in Kandahar, and the displacement of people in Hazarajat and in the North, once known as Qataghan.

Still, the evacuations are all I can think of—and there are more evacuation group chats. Sensitive material like passports, tazkira (Afghan identity cards), and phone numbers are passed around from phone to phone hoping to make evacuation lists. Some make it. Many do not.

We are pulled in all directions, sleepless, trying to coordinate evacuations for people we know because as American, or Australian, or UK citizens we have some connection that allows us to contribute their names to lists for airlifts. We fill out spreadsheets. We make Google Docs. So many. Who is more at risk? Who is more vulnerable? It is answering questions like these that hurt us as we write emails of support, inquiry, demands. I make one family my priority. They have SIV pending P2 pending with a LPR parent. These are new acronyms we use: SIV, Special Immigration Visa; P2, employed by an American NGO or Media company; LPR, Legal Permanent Resident aka Green Card holder. If they fall in these categories they have a high chance of being evacuated. But what happens to their sister who has none of these and has two children? They ask for a car. I think of my privilege. I assumed there is public transportation to take an elderly woman and two small children out to the airport. I can’t provide a car, I’m just a teacher, I say. I have no idea how to call for cars in Kabul. I’ve never even seen the city myself. But I get them on a list with a senator.

Finally, they are called to evacuate at 4 am Kabul time. They shared the message from the U.S. embassy with me on WhatsApp. It is a man speaking with a flat midwestern American accent. He speaks slowly and clearly. The voice tells them to calmly take their things and get to the airport as calmly as possible. The voice says, do not listen to the media news about chaos at the airport. It is important to be calm at all times to get out. The voice is reassuring. It almost erases the news images from the airports, the days-long waits, the pushing and the Taliban whippings. Their old translation firm sends them a car. I spent all night praying for them. I am afraid to text them in case the Taliban checks their phones. I don’t hear from them for days. But then, I get a text—the family didn’t make it out after going through a Taliban checkpoint. They miss the August 31 deadline. They write to me. “We’ve been left behind! Sister, can you find a way to get us out?” I try again to reach every senator publicizing that they are evacuating Afghans and Americans. I try the organizations, try the friends, but the planes have stopped. And I have no way to help. There is a searing pain of uselessness that I never felt before in the face of so much no, no, no that Afghans face.

The Taliban blows up a cell phone tower interfering with the communications needed to get people evacuated. Another friend, a girls’ high school principal who is also a poet, has come to Kabul from Mazar and has had four false starts. There are invitations, calls in the dead of night, secret words—orange or apple or purple—to know this is a trusted person. She joins a group of other writers scheduled for a flight to Italy. They waited 30 hours outside Abbey Gate on August 26 to get through the final checkpoint. The gates are overwhelming. The Taliban whip people who are outside the gates. The American soldiers treat them inhumanly. The vets helping their Afghan friends get out say the soldiers at airports are young and they are reserves. They do not know anything about Afghanistan. It is these young soldiers’ mistreatment that turns away my friend and her group. The bomb explodes at Abbey Gate ten minutes after they walk away giving up their spots in line. They are saved. The soldiers may not have made it.

There are so many calls from friends, family, and casual friends we knew on social media. They tell us of many false starts, and more stories of complete failures in the face of the chaos of trying to leave Afghanistan. They are stuck circling Kabul airport in a bus. There is a Talib in the bus! How to get him out? And then more circling around the airport before going back home. A WhatsApp message, a voice note giving orders, hope and anticipation at one’s throat, and then nothing, only disappointment and a return home. These are the stories that so many left behind have. These are so many of the kinds of texts and emails we receive.

Then the flights stop. Then there is nothing, no messages, nothing other than consoling phrases from poems telling us to be patient. We pass these lines on to those waiting to hear from us. There are no more evacuation flights left.

Land routes are next, they say. The militaries have left. The green, night vision lensed-photo of the last American soldier is all over the news. He has fear in his eyes. He reminds us of the last British soldier who left Afghanistan in the 19th century. The media use the same tropes, “Graveyard of Empires.” Maybe the empires should stop trying to make Afghanistan their example of imperial might. The pull-out looks like a cheap stage pulled down after a show that had hypnotized many.

The people now take land routes to Pakistan. Even with valid visas, they are turned back from borders. My friend says, a man trying to escape over the border was eaten by a hyena. Then goes on to explain Humanitarian Parole and visa applications. His death is just one of so many. I am dizzy from the paperwork. Flashbacks to my childhood translating immigration applications and deportation letters from English to Uzbek. I see my young friends turn into my parents who came as refugees here in the 1980s. Like so many of us doing this paperwork, we see our parents, we see ourselves in the people we are working to get out. Meanwhile, those who are evacuated struggle in the detention centers or processing centers. Many have lost their luggages on the evacuation flights. Others are sleeping in tents. They miss the sunlight in their homes in Afghanistan. The things they saved are now relics of their homeland just as they were for my parents.

People risk lives for the land routes. There is a road of dead babies, they say. They didn’t survive the journey. When they finally reach the Pakistan border hundreds are sent back to Kabul. If they were born in the North, they are turned back right away. If they have a visa, they are asked for a Gate Pass. Each costs more and more as bribes become part of the price. Now the Gate Passes have been stopped. In the group chats, the questions are like this: Which route is better, Torkham or Spinghar? Can you send me the GIS maps with notes on where the Taliban checkpoints are the strongest? We know how to trace flights out of Kabul. There are more maps and reports. We are in a virtual Afghanistan. It is a crash course on Afghan geography. I learn that in 20 years no one developed the roads inside Afghanistan. All developed roads lead in and out of Afghanistan. The map I look at is the colonizers’ map of Afghanistan.

The texts and the group chats take up so much of my time. If this is activism, it is all work I do by typing and texting. There are so many group chats that I don’t even know how I have been added or how I started these. 100+ texts a night. But who is sleeping anyway as we count how many we are able to get on the planes.

We are still texting those we promise to get on those evacuation planes. The family for whom I first began writing to senators for help are no longer communicating with me. I cannot get them a plane. I understand. I turn to other families and to support women who are stranded. We get a few out. We get no one out. We get everyone out. We raise funds. We find pro bono lawyers. We have our funds frozen by GoFundMe, but we are supported by Chuffed and Venmo. We raise the $575 application fee required for each person in the family that we are applying for Humanitarian Parole. My small indie press, UpSet Press, is supporting a family of twelve members. They are literary and artistic treasures. They are educational activists and practitioners. They are from the provinces, with no connections to institutions. How can we afford these fees? My former student, Mayha Ghouri, joins in the work. She has been processing Humanitarian Parole applications. She takes on the family of writers, teachers, principals and supports by even finding funding. I am lucky for this community of support. My friends who support their own families and friends and respected strangers ask, how do we find more American sponsors for the people we want to help out of Afghanistan? How do we help those facing threats? Those who worked with the government? Those who run schools for girls? Those who ran youth programs? I am asked, “What kind of activism do you do?” I am no activist. I simply coordinate and channel and connect hundreds of texts and emails. Facebook Messenger. WhatsApp. Signal. So many new programs. These are how corporations are woven into our coordination work. So many new strangers, so many emotions, so many new networks built on goodwill, trust, and loyalty to old promises or friendships. Governments close their borders, turn their backs, flee, collapse, forget, ignore—but the people go on filling in those spaces, filling out forms, pleading for the safety of their friends and family, or simply respected strangers who had been activists, journalists, active participants in gender equity, builders, and those who critiqued, spoke out, glared back at the devastating cruelty of violence, despotism, and authoritarianism.

What would Farhad jan think these 15 years since his death? Farhad, who encouraged Afghan Americans to serve, to rebuild, to unite… what would he say? Was his sacrifice worth it? He left behind $50 in his bank account, a fiancé, a half furnished apartment in Virginia, and student loans. Would he be with us scrambling to get people out, making sure people left behind have safe houses, and apply for their visas? Yes, I know he would.

The family in Kabul is split up. The younger family members, the ones with SIV applications pending, are evacuated to Doha. My friend, the girls’ high school principal, returns to Mazar i Sharif and goes into hiding waiting for an evacuation. My friend from Kandahar, a young woman who builds schools in the rural areas, makes it to Boston. We are ecstatic for these wins. We fight for those left behind. This is what it is like for Afghans 20 years after The War on Terror, 20 years after 9/11, 20 years of drone wars, and 20 years of living under a glass bell as an example of successful state building that was all for show, a display, without roots grown into the earth.

The world forgets us. The world does not see us. The world turns its back on us, Afghans. It lures us with false promises then deports us. But love, love is the only way to push back the doors that are shutting. I have not seen love, and I have not seen courage, and I have not seen hope as strong as I’ve seen in the Afghans I have met. It is with this intense hope that one can move an entire family to a border, be turned back, and then try again.

Will the world just sit idly by in the face of this catastrophe in Afghanistan and turn away the refugees?

Evacuation Support for Afghan Literary Family

UpSet Press Inc, a small independent press based in Brooklyn, is sponsoring an Afghan writer, an Afghan teacher, and a family of 12 members, comprising of three separate family units, for Humanitarian Parole. The fundraisers must keep this family’s identity anonymous because they live in the provinces and are in hiding.

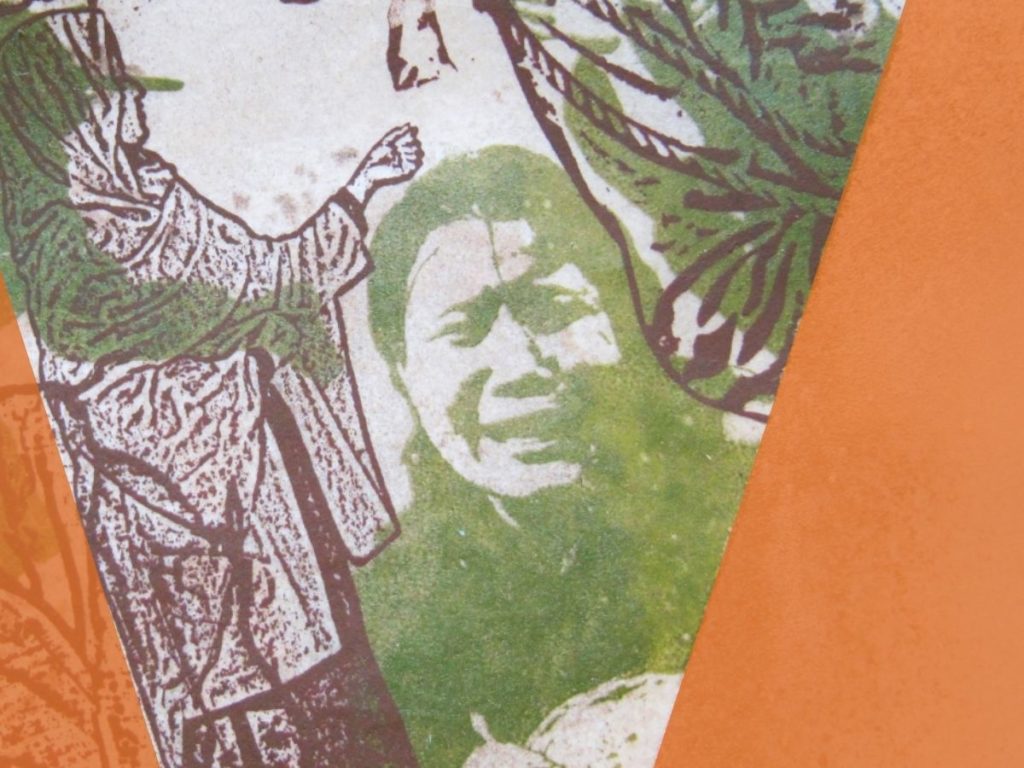

A note about the art: The image that appears atop of this conversation is adapted from the artist Tomie Arai’s “The Shape of Me,” a silkscreen monoprint created in response to a national call to artists issued by the American Friends Service Committee for the 2011 exhibition entitled “Windows and Mirrors: Reflections on the War in Afghanistan.” We are grateful to collaborate with Tomie for our notebook Living in Echo. Find more of Tomie Arai’s work here.