The campus was haunted and we all knew it. That summer we flinched around every corner, put our hands out in front of us when we turned off the lights.

September 27, 2018

From the top of the flight/ of the wide, white stairs/ through the rest of my life/ do you wait for me there?

—Joanna Newsom, “Sawdust and Diamonds”

.x.

“I bet you one dollar that you can’t keep your mouth shut the whole car ride back,” Marianna said.

It was a game, which is what I kept telling myself on the way back to campus. They only meant it as a joke. All kids do. This was before I knew the things I know now, back when before was just before, when I didn’t have it in me to take its knotted ugliness in my hands and unravel it into what happened at camp.

We’d splurged on iced soda and hot dogs and Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups at the gas station, snacks that would last us the rest of camp. Our dormitories were so isolated that it was hard to find food when we weren’t at meals. And all of us were hungry that summer. The heat made our jaws snap. We jumped at the opportunity to do a midnight gas station run with the camp counselors.

Annabelle was laughing from shotgun. The windows were down and we let the air blast the sweat from our skins. Mack, our Virginia Woolf-obsessed New Yorker, and Annabelle, the one poet in our group of fiction writers and playwrights. Jeannine who had a stuffed tiger she carried everywhere. Abigail whose nice mom sent us a suitcase of snacks we’d finished in three days, Marianna the military brat, Jules who drew cool art, Amy who taught us all how to repel creepy guys. We drank our sodas and felt the silence of the radio and viciously hated the heat. We imagined our brains seeping out like egg yolk from our cracked skulls and cooking on the pavement.

We gossiped and chortled and let our eyes roll back into their sockets. We dissected every topic we could come up with—Tumblr and feminism and One Direction songs, which high school writing contests to submit to, the process of starting queer culture clubs in our schools. Somewhere in all the muddle, Mack said I talked too much at lunchtime.

I immediately grew defensive. “No I didn’t,” I said.

“You’re a blabbermouth, it’s who you are.”

“No, I’m not.”

“You do talk a lot, you know,” someone else said. I tried to turn and see who it was but the seats behind me were a jumble of limbs and light hair and smacking lips. They were chillingly identical in the dark.

Jules chimed in that being a loud, talkative person was feminist.

“You can be feminist and also not a blabbermouth,” Mack said.

“I’m not that bad!” I didn’t know who I was trying to convince. “I think that I, you know, talk a normal amount.”

“Nancy, you never shut up!” It came from the gaggle of girl in the seats behind me. I didn’t want to turn around again and see them, lined up in front of the van’s back window, uniformly indistinguishable. That’s not fair, I remember thinking. If it were any of you I’d have defended you.

“Wait. I have an idea,” said Marianna.

.x.

There’s a light in the wings, hits the system of strings/ From the side, where they swing—/ See the wires, the wires, the wires

.x.

(The word ghost has been around since before 900, when Old English was spoken. Its meaning hasn’t changed: existing without a body.)

The summer of my sophomore year, my mom convinced me to go to writing camp.

She didn’t want writing to just be a hobby. She wanted me to have direction in everything I did. These camps were competitive, and they weren’t cheap. They were affiliated with universities, had sleek websites with beautiful pictures of ivy-covered campuses, promised exciting summers full of outdoor activities and good food, and were backed by literary prestige.

My mom and dad were convinced that I would form meaningful connections at these camps. They both encouraged me to go. My friends have often told me that my parents’ support of my writing is unique among Chinese parents, who tout ambition to their kids, so long as it’s not in the arts. But I’ve always known that my parents have engaged with the arts. My father wanted to be a musician when he was younger. My mom eats up Chinese literature, is a fan of Impressionism. I received an acceptance letter, a packing list, and a welcome pamphlet. My parents were able to pay the tuition. I was going.

.x.

Then the slow lip of fire moves across the prairie with precision/ While somewhere with your pliers and glue, you make your first/ incision

.x.

Mariana proposed the bet: one dollar. Two postage stamps. A cup of coffee. A song on iTunes.

It was twisted. No matter what I did I’d lose. But at least if I played along I’d be what they wanted, which I think is what I wanted most.

“Deal,” I said. The air vacuumed out of the van. Our driver Eddy had pulled the windows up. It was midnight and we watched the black outside move past us like a dangerous animal. The campus was haunted and we all knew it. There was a bee infestation in the dorms and we could hear the eerie buzzing in our workshops, in the hallways, in the creaking elevator, in our dreams. That summer we flinched around every corner, put our hands out in front of us when we turned off the lights.

Annabelle was chewing hard, gum straining against her tongue as she popped it into a bubble. “I think she’s gonna make it,” she said when Eddy pulled up to the gates of the campus.

“Damn,” Marianna said. I took her dollar and tried to feel triumphant, which didn’t work. We unfolded ourselves from the car, hiked back to our dorms. I tried to put away the strange feelings I had, the tangle of anxiety and hurt and something I recognized from my younger years, the yearning to just fit in. There’s a certain damage that can carry over from one’s youth, from the formative experiences that make up most traumas, habits, or moments of happiness.

That van ride was years ago. It was harmless, between friends. It wasn’t even violent. Or just a different kind of violent than I was used to.

.x.

Push me back into a tree/ Bind my buttons with salt/ Fill my long ears with bees/ Praying please please please love

.x.

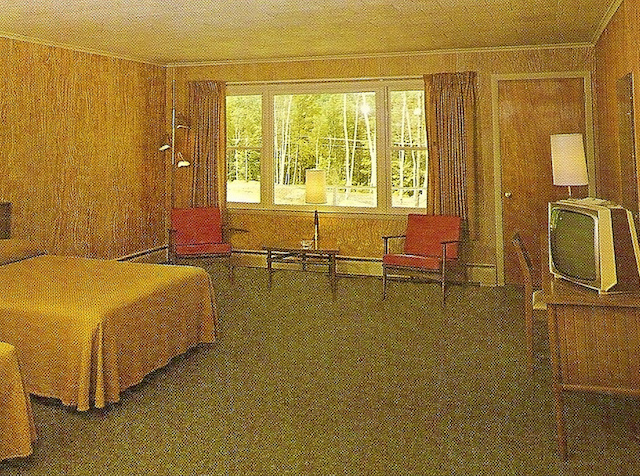

The camp, one of the oldest youth writing workshops in the country, is held annually on the Colonial Revival campus of an all-women’s liberal arts college in Virginia. The school is empty during the summer, secluded from the rest of the world.

I often heard other campers say that they had stepped back in time, taken to a place where the country was verdant and the minds more so; there were acres and acres of land, most of it woods. Red brick and cobblestones. Airy classrooms and a yellow mansion in the distance.

The property, built in 1825, used to be a cotton plantation with around 110 slaves. The land it stood on was home to the Monacan people and other Siouan Tutelo-speaking tribes. This wasn’t history that we were privy to, as high schoolers living in the beautiful, spacious dormitories for three weeks. We were never shown the fields, the cemetery, or the old slave quarters. No one told us that some of the slaves’ descendants still work at the school and throw annual family reunions on campus. No one told us that the Tutelo language evolved to incorporate words from African languages because local tribes were known for sheltering runaway slaves. We knew nothing of their lives or coded resistances. Ours was a bleached space. A whitewash of history.

Instead we were told stories about the wealthy Williams family who owned it all, their grief when they lost their 16-year-old daughter Daisy to illness, the time her uncle destroyed her grave in a drunken rage, the family’s decision to start a school for white women in honor of Daisy in 1901. Black women couldn’t attend the college until 1966.

Whiteness can make a ghost out of you. It can detach you from your own body. I think daily of the way I move in the world in a queer Asian female body. It’s a focus that solely centers my experience. I am trying to ponder instead on the collective history of each space I occupy, to look outward. Failure to inquire about this results in an easy amnesia.

The bees that infested the dorms didn’t sting but they hovered close enough that you feared the needle prick of pain constantly. I was careful about the way I moved in and out of rooms, about the way I gestured, the way I sat in my chair and opened my books and tied my hair. It wasn’t just because of the infestation. There were maybe six other non-white kids in a camp of 80. All the faculty were white or white-passing. The cost of the camp guaranteed the racial makeup, but that wasn’t the whole picture. I was fifteen and already I knew how to navigate an all-white space, a skill that comes in handy when you grow up Asian in the Midwest. I was incredibly privileged to be there, so I felt ungrateful for feeling Othered.

This was my first impression of any kind of writing community. I was glad to take part, but I knew my role was to be a cushion for whiteness. This was all I had.

.x.

So enough of this terror/ We deserve to know light/ And grow evermore lighter and lighter

.x.

(In Middle English, haunt used to be another word for home.)

“Anyone know what ekphrastic means?”

Workshop hadn’t started yet, but we were all seated at the round table. Our writing counselors Megan and Jordan were plugging speakers into the wall. They filled our days with prompts, gave enthusiastic feedback on our drafts, and taught us craft lessons. The classroom was cold, so we loved it. Buzzing was coming from the windows and we kept them closed. Winston, a boy who talked about the Beat poets constantly, raised his hand.

“A writing inspired by music.”

“Mmhmm. Or any kind of art, really. We’re going to listen to a song and then do some freewrites.” Megan hit a button on the speakers.

“I really love this song,” Jordan said, plugging a wire into his laptop. “It’s very interesting. Everyone I’ve played it to never knows what it’s saying. And I don’t think the point of the song is to have a specific meaning. I want you to pay attention to the lyrics and write what you think the song’s about.”

We listened to “Sawdust and Diamonds.” The buzzing at the window stopped. Gentle harp and Joanna Newsom’s quavering voice. It was witchy and fragmentary. How gorgeous and odd, I thought. I didn’t know what to make of it.

I spent the morning puzzling over what the lyrics could mean. She sang about wires and strings and salt buttons, ears full of bees, the sea. I closed my eyes and saw a carpenter’s workshop. I wrote about a sailor carving a mermaid masthead who falls in love with her creator, but because she’s a piece of wood she can never tell him. Newsom was singing about love, but there were incredible violences in the song, too: cutting open the bodies of birds, stuffing them with sawdust and diamonds, gluing them back together.

There is nothing violent about poetry. There is everything violent about poetry. I think the story I wrote, alongside the song’s taxidermy, was on the same frequency of what I thought of ghost girls: immobile, stuck outside of time, the eternal observer. Haunting can also mean taking ownership of a physical thing, possession, which expands the definition of “ghost”: You can have a body. You can put your skin back on. You can never take it off or escape it. But at least this way you exist in the only way that matters.

I wasn’t writing about anyone else. I was writing about me, and all the other girls who I didn’t know about yet but who I was sure existed, and were living in someone else’s margins. The heat, the campus, the song—everything reminded me of that truth. You have a body. You have a body.

.x.

Hold me close, cooed the dove/ Who was stuffed, now, with sawdust and diamonds

.x.

I didn’t have to say yes to the bet. I could have refused the dollar. I could have proven what they all thought of me anyway by talking their ears off: about the bees, the ghosts outside, the way Virginia was trying to kill us with heat, how all three could be related. I should have.

I shared a suite with eight other girls and a counselor, all white. At times I unfairly resented them. They had an ease I lacked. They got along so quickly. I retreated indoors while everyone else wrote outside. I stayed in my room when I could have socialized in the mezzanine. I was more withdrawn during our end-of-the-day chats. The other girls blended in with their surroundings. It felt like more work to befriend me. I learned not to expect better.

.x.

And the moment I slept, I was swept up in a terrible tremor/ Though no longer bereft, how I shook! And I couldn’t remember

.x.

(Evidence suggests cold spots—temperature dips felt in haunted areas—are a result of a fluxing magnetic field.)

“Time for ghost stories!”

Tim and Eddy were clinking glasses. The other counselors were all gathered together in the kitchen of the dorm common area, pouring drinks. The rest of us scattered around the room, mostly laying on the floor. I sat down next to Jeannine and Amy, the three of us crowded in front of the room’s only fan. Someone turned off the lights.

“Y’all know that this campus is haunted, right?” Janet, a poetry counselor, kicked her feet out from where she was perched on the kitchen counter.

I shivered and moved away from the fan.

“It is?” Eddy asked.

“Yep!” Janet shared the story of the Williams family and Daisy. “And to this day, all the students who go here say you can sometimes see her in the main hall. She also cleans the blackboards when no one’s looking.”

“That’s wild.”

“Don’t worry though, she’s a very friendly ghost! There’s no need to be scared if you encounter her.”

We sat with this, fascinated and unsure. I was wary of anything I couldn’t see. There are only so many things you can erase. I imagined some invisible hand scrubbing away at a blackboard of lesson plans from the previous day. I imagined attending school with a spirit who left messages in chalk.

We told ghost stories with the counselors and traded real-life horror tales. The woman with no eyes behind every keyhole, the girl in white who appears in front of your car when you’re driving down the highway at night, the times you can hear someone laughing in the crackle of radio static, the student who hanged herself in her dorm and whose body still swings to the wind. Back in our dorm, Mack announced that she absolutely believed in ghosts.

“Mikaela’s story was so scary. Because it was real!”

“Daisy’s was real too,” I pointed out. “And hers is way more scary.”

“Daisy’s friendly. Everyone says so!” Amy called from her room.

She’d misunderstood. I was thinking about the idea of someone tied to a particular place, and how hard it might be to stay there for all eternity, even if it was home. I wanted Daisy to be able to wander. I thought the entire point of ghosts was to stop being bound to things.

I slept in Amy’s bed that night because we were both too scared to sleep alone. The night before I’d heard something snap in my room, a loud clicking that vibrated. I thought it was the shutter windows, but there was nothing there. I felt the strongest presence. I knew somehow I wasn’t alone.

That was how haunting worked: a constant occupant, like someone being in a room with you. I never got an answer that summer, about that noise, that presence. I compartmentalized through poetry; I went back to high school and wrote a series of poems about Daisy. That projection on empty spaces, isn’t that what ghosts do? This was an environment where I was seen as an anomaly of my personhood—a Chinese girl trying her hand at writing—but also as an anomaly of the space I inhabited. I was young and impressionable and didn’t ask the questions I should have been asking out of fear of retaliation, of erasure, of being silenced. That van ride, my workshop cohorts. I kept quiet to avoid being told to keep quiet.

.x.

But if it’s all just the same, then will you say my name;/ Say my name in the morning, so I know when the wave breaks

.x.

In stories and on the screen, Asian women haunt your nightmares. Asian female ghosts kill, slaughter, devour white bodies. They do not speak. They feast on souls, lurk in your periphery, bathe in your blood, relentlessly pursue indiscriminate victims.

Uncalculated motives make their violence more terrifying; they kill anyone, everyone. They appear anywhere. They are boundless, absorbent, and hungry. Their home is you.

I’ve heard people say that it’s proto-feminist, the way revenge narratives are a redemptive kind of violent poetry, the way these ghost stories could actually be examples of coded resistance about what living and dying as a woman in medieval Asia entails. I believe it’s a useful trope that serves its specific purpose. Still, I only remember the loneliness I cultivated for myself that summer, so potent it felt like I was cracking down the center. I remember I was obsessed with ghosts and just starting to believe in them. I remember that an entire colony of bees hummed a constant orchestra in all the buildings. I remember that summer as isolation, as a certain kind of aloneness.

I still think to ghost something in writing can mean erasing a body instead of announcing a presence. I admit that sometimes to be rendered invisible can be convenient. I admit to taking advantage of shortsightedness. If only I could exist that way, I used to think. If only I could be raceless, sexless, bodyless, wandering the world on my own terms. If only I could have been a ghost in that van ride all those nights ago. There would be no need to sell my silence if I’d never been speaking in the first place.

But that isn’t the point of ghosts in stories. The point of ghosts in stories is to serve as metaphors. All ghosts are metaphors for the past. I wish I’d known that. I wish I’d known that to be silenced is to be something other than alive. I can be in my body and still find a new home. I deserve to be something.

.x.

And though our bones they may break, and our/ souls separate—/ Why the long face?

.x.

(Phasmophobia = the fear of specters, ghosts)

What I really mean to say is, camp was an education in haunts. I mean to say, if I hadn’t gone I would never have gotten to where I am now. I mean that the history of the land we stood on had everything to do with visibility and body. I mean to say that I wasn’t dead yet; I should have said something in that van and I didn’t.

I mean that during workshop someone asked me if my narrator was Asian, and I lost what I was writing for, that easily. I mean that someone told me to put my skin back on. No one in my story had a body, and that used to be the way I survived. At the time it freed me from having to think about myself as an anomaly. There is a place in me now where the opposite is so much more freeing—writing that is grounded in identity and in how I present.

What I learned at camp has so much hold on who I am. Workshopping, the music of ghosts, how much it takes to gain access to privileged creative communities, the way art grounds me in spaces where I don’t feel welcome. I am grateful I attended, could afford to attend. I am relieved that nothing worse happened. I don’t live in your margins. I deserve to be something.

.x.

Oh, oh, oh, desire.

.x.

Here is what I should have said:

I don’t need a dollar. I’m not going to be anything silent. I’ll tell a ghost story instead. The story goes like this: there are women who only exist if you speak about them. If you are one of these women then you will die in a horrible way, in old countries with folktales that are familiar only to me. Your spirit will live on, free to enact even worse violence on the ones who made you a ghost. Most things hate and despise their makers. You are no different. You will not be different. When you come for them they will recognize you and be surprised. But of course you wear a familiar face. You are the end, and everyone knows the end is coming. That is real intimacy. You have a body but you can slip it off when you need to. You have a face you can remove whenever you want. You have skin but it’s not a trapping. The physical is fantasy. Your existence is not contingent on anything. Most people are scared of stories like this. They don’t see you for what you are, which is free, uncorrupted. Recognize that you already died once. I used to be afraid of you. People used to be afraid of us.

This story is part of a special issue of The Margins around the theme “Camp.” Look out for more essays, stories, and poems in the issue in the coming weeks.