All the koi fish in our pond died, except one.

December 21, 2022

All the koi fish in our pond died, except one.

The pond was at our old house. That morning my mom got a text message from the new tenants. They were freaking out and didn’t know what had happened.

“Everything was normal!” the new tenant said in her text.

My mom sent her the phone number of our pond guy. He promised he would come immediately. The new tenant asked my mother if she’d like to come look as well. She didn’t.

You could tell my mother was upset. She spoke in sentences shorter and more clipped than usual and moved abruptly in a way that suggested that she was angry, but which really meant that she was processing.

“This happened before. When we first moved into that house, all the fish suddenly died. It happened twice. Then we got the new fish.”

She brooded. “We raised those fish for four, five years,” she said.

Then she asked me, “Do you want to go?”

“I can go see if you want.”

“Okay,” she said. “You should go see what happened.”

“You don’t want to come?”

“I don’t want to go and see all those dead fish,” my mother said. “So sad.”

We were about to head out of the house. I asked her if we could switch cars for the day. My rental guzzled gas, and the old house was an hour’s drive away. Her car had engine problems, but that was preferable to the gas. She usually didn’t like for me to drive her car, but she passed me her key.

She left the house and drove away in my rental.

I put on eyeliner and got my bag. I started to head out and got a phone call.

“Actually, let’s not switch cars,” my mom said.

“What?”

“That car has engine problems, and I feel like it’s unreliable. And I just got this feeling—”

“You drive this car all the time.”

“I know how to handle the car, but you don’t. It’s better to be safe.”

“It’s fine,” I said.

“But all the koi fish died today, I don’t know.” She stopped. “I feel like this is unlucky.”

We met a few streets away and switched our cars back.

I drove to the old house. The new tenant opened the door. In the backyard there was a strong, marshy, wet smell. The pond was a rectangle, perhaps six feet by three feet.

“Is this smell always here?” I asked.

“Maybe it’s from the dead fish?” the tenant said.

The pond guy had already come and gone. The tenant said he had taken all the fish away, except for the last one alive. I went to look at it. It was a small white fish, a sad remainder of the red-and-blue long-finned beauties my parents had raised.

“Maybe that one is a different breed, maybe it’s hardier, I don’t know,” the woman said.

“So everything was fine? Nothing unusual?”

She said she and her father had been sitting outside by the garden doors drinking coffee. The woman had stirred and said, “Hey—isn’t that fish dead?” She stood up and walked to the edge of the pond and saw it was full of fish corpses, some sunk to the bottom, some floating at the top.

“It must have been very upsetting,” I said, imagining it.

“Everything was completely normal yesterday. We fed the fish just like we usually do.” She showed me the calendar she’d been using to mark the days she fed the koi—every three days, as recommended. “They all came and ate the food just like normal.” She repeated the words normal and usual several times throughout her speech.

She said the pond guy had come and gone with a sample of the water. They would test it for anything unusual.

We speculated, but we didn’t know anything. We could only theorize. Was it the heat wave? Perhaps the temperature control in the water had broken? A sudden sickness, a parasite? How could they have all died at once, overnight, with no warning?

There must, I thought, be a scientific reason. For I had been raised in the age of rationalism, by atheists, in a time when scientific progress and enlightenment reigned. If this mass death was an omen, then science would fight it. There would be a reason that would dispel the sense of doom. For in science there is always a cause and an effect. This is an attitude I cannot shake—the trust that there was a reason neutral to fate.

And yet, in my life, I have wished to believe in omens. I have prayed in temples and lit incense, fingered the beads of Buddhist bracelets, knocked on wood, counted to three. Two and a half years ago, I bought a stick of fragrant cypress shaped like a key from a Japanese temple and hung it on my wall for good luck during a move, but a month later, woke in the night to the sound of it falling, split in half at its weakest point. In the night, I thought it was bad luck. In the morning, I glued the thing back together. Perhaps it was an ill omen, considering the turbulence I’d faced since then, the desperate measures I’ve been forced to resort to, and yet I could not really believe in my superstition.

These days the world is full of what were once thought of as omens. Fire, rain, wind. The weather changing. Thousands of years ago, we would have built a bonfire, sacrificed goats, chanted day and night, and prayed.

The woman had taken a sample of the water for herself in a bottle. She asked me if I wanted it.

“Sure,” I said, not knowing what to do with it. The bottle was a plastic one the size of my palm. In it, the water was perfectly clear.

We looked at the pond. The water was green, the color of the algae growing at the bottom. The last fish, white as a ghost, swam slowly, lingering in the shadows of the corner of the pond furthest away from us.

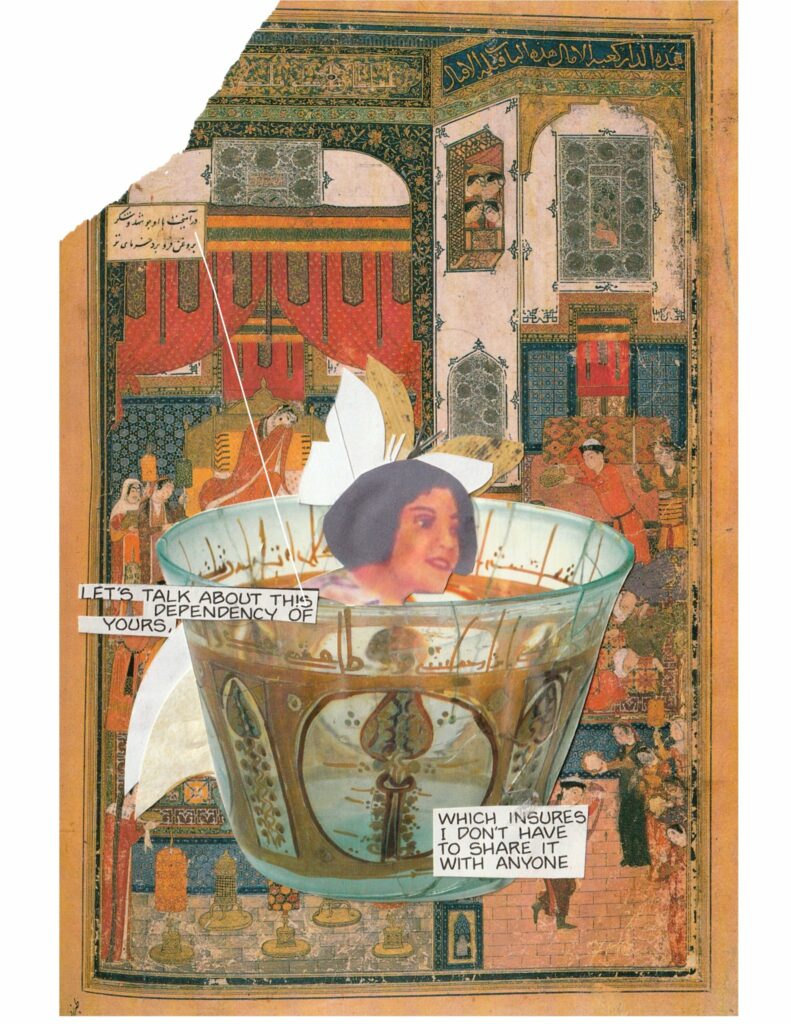

This story is part of the Remains notebook, which features art by Chitra Ganesh.