“I don’t think that writers choose their subjects. I think they choose us. I think they step out of history books, off the sidewalk, or from a near future, and they say, ‘Hey, fool, you’ll be writing this one!'”

September 12, 2019

For much of the 2010s, the generous and brilliant Monique Truong was researching, traveling, and writing her third novel, The Sweetest Fruits, which released in early September 2019 from Viking Books.

By some metrics, The Sweetest Fruits encompasses the broadest scope she’s tackled yet. The work features three main narrators living across the world in the late 19th century: Rosa grew up in Cythera, a small island in the Ionian Sea; Alethea lives in Cincinnati, Ohio by way of antebellum Kentucky; and Setsu lives in Matsue, Japan. Before Truong’s book, these three women’s narratives were only known from their connections to globetrotter and writer Lafcadio Hearn. Truong uses these biographical links to give each of these women’s stories its own life while creating a novel of her own.

As with her first two books, The Book of Salt and Bitter in the Mouth, the tender subtlety with which she evokes characters’ relationships reads with a force that’s distinct not just by Truong’s musical, crisp sentences, but by the depth of imagination in her storytelling.

In this interview, Truong reflects on how her travels and research helped call forth the voices of her characters. When we first met in January, our discussion called to mind Professor Saidiya Hartman’s celebrated 2008 essay “Venus in Two Acts.” Hartman examines the impossibility of recovering the figure of Venus as an enslaved woman from the violence of the archive. She proposes “critical fabulation” as a way to “negotiate the [archive’s] constitutive limits” and “imagine what cannot be verified.” I sent Monique the article and when we began our interview in June, murmurs of Hartman’s ideas resurfaced.

But first, we talked about a movie.

—benedict nguyễn

benedict nguyễn

Where are you finding pleasure in this late June, spring to summer transition?

Monique Truong

The second time I watched Always Be My Maybe. The first time I was too anxious, hoping and willing it not to suck. It didn’t. It was frothy and light. It was funny and Keanu [Reeves] looks great in all black. I’ve watched the movie three times now. On the third viewing, I was fixating on Sasha’s [played by Ali Wong] hair. How thick and gorgeous it is. How many iterations were possible given the length of it. Pleasure, in this instance, [was] maybe the simultaneity of forgetting oneself and seeing a self.

bn

How did your experience (as a person as much as “writer”) to Greece and Japan shape this book?

MT

I spent three months living in Tokyo with trips to Matsue, Kyoto, and Hakone. When I teach creative writing and my students ask me about getting a MFA, I tell them to travel. The “instead” is implied. I tell them that to travel is to learn about oneself and not necessarily to learn about the other. I can guarantee them the former will happen, while the latter is a possibility and far from assured. I tell them to leave their familiar languages, spaces, and milieus. By familiar, I mean “comfortable.” I think some people think that they become someone else, someone not themselves when they travel. I think we become our unvarnished, unmasked selves. If that’s indeed true, then it’s a paradox, yes? We travel far from home to be most at home.

At the heart of The Sweetest Fruits is a traveler, Lafcadio Hearn, a writer who circumnavigated the globe. The women who tell his story and their own are also travelers in their own ways. Geographic distance is only one measure of having traveled. Crossing national borders is only one demarcation of having been somewhere else. When your known world is as circumscribed as those of Rosa, Alethea, and Setsu, three of the women in The Sweetest Fruits, to walk out your front door alone can be and is the equivalent of crossing the expanse of the Pacific.

bn

Back to Always Be My Maybe, I was also struck by Sasha’s gorgeous outfits! Any particular favorite looks from the movie?

MT

Wardrobe for her was ama-ZING! No doubt. I loved her shoes. Platforms are heels you can walk in. Necessary for us shorties. Also, chefs tend to have terrible foot pain, as they’re often standing all day long. I’m glad that wardrobe did not put a chef in stilettos, even for her nights out. I also adored Jenny’s [played by Vivian Bang] sartorial flourishes. If I’m being honest—which of course I am because I wouldn’t lie to you, Benedict—I’m more Jenny than Sasha. A bit of a mess, thrift store finds, more style than fashion.

bn

I do feel like I’m more Jenny at the heart of it (minus the dreads) but sometimes cosplay Sasha’s glam. What about any memorable sartorial musings from your travels?

MT

While researching The Sweetest Fruits, I lived in Tokyo for three months courtesy of a U.S.-Japan Creative Artists Fellowship. It was the second time that I had traveled to Japan, and I brought home with me four kanzashi (hair ornaments) that my friend Mariko helped me buy at an outdoor antiques fair in Tokyo. Two kogai (a stick shape with the same design element at both ends), one tama (a two-prong stick with a rounded element at one end), and one made of bone and a green stone, whose type I do not know the name of. I don’t like to bargain, so I didn’t ask Mariko to do so on my behalf. I was grateful to afford them. I’ve rarely worn them. I didn’t include them in the novel, though they would have been at home there among Setsu’s possessions. The ornaments bring me much joy because they were designed for Asian hair. Black, glistening, long. We don’t always have to display what brings us joy. Sometimes it’s enough to know that they are there, if we need them.

bn

What did it mean to for these characters—Rosa, Alethea, and Setsu—to see themselves within the worlds they lived in? How did you as a writer try to varnish and unvarnish them in different settings for The Sweetest Fruits?

MT

The first-person narrators in The Sweetest Fruits: Rosa Cassimati, Lafcadio Hearn’s Ionian Islander mother (now a part of Greece), whom he referred to as “Oriental”; Alethea, Hearn’s first wife, who was born into slavery, and was a young cook in post-Civil War Cincinnati when they met; and Koizumi Setsu, Hearn’s second wife, whom he met in Matsue, Japan, in 1891.

There’s also a fourth woman, Elizabeth Bisland, Hearn’s longtime friend and perhaps his true love, who was his first biographer. Excerpts from that biography serve as a framework for the other three voices. These excerpts function as the archive and the “fictions of history” as Professor Saidiya Hartman refers to in “Venus in Two Acts.” That essay is essential reading for anyone interested in writing historical fiction, especially about or from the point of view of “the subaltern, the dispossessed, and the enslaved” (Hartman). Within the pages of the The Sweetest Fruits, I leave it up to the readers to determine whom to believe whenever there are discrepancies or counter-narratives between and among Elizabeth’s account and the voices of the three women.

Of those three voices, there were differing levels of documentation available, so each presented different challenges for me to “varnish,” as you so aptly characterized the process of character construction. Rosa, for example, could not read or write, so there is no correspondence by her or to her. She left us no trace of a written self, only the stories that were told about her by Hearn and by others. Alethea also could not read or write. According to Hearn, she was an engaging storyteller. In one of his feature articles—he doesn’t identify her, but it’s clear and widely accepted by historians that the piece is about her—he writes in her voice. Alethea’s stories were about “ghost people” and presumably told to her during her youth in antebellum Kentucky. Hearn’s eventual literary fame would come from rewriting the ghost stories of Japan. It was easy for me to imagine why Hearn was attracted to Alethea. It took a bit more time [for me] to imagine why she would be attracted to him though.

Alethea also left behind another—what I think of as a “scrimmed”—document of her voice: an interview that she gave to a Cincinnati reporter in 1906, which purportedly told the story of how she met Hearn and the circumstances of their marriage. The reason for the interview was an example of what Professor Hartman calls “an act of chance or disaster” that “produced a divergence or an aberration from the expected and usual course of invisibility and catapulted her from the underground to the surface of discourse.” For Alethea, the “disaster” was the shock and indignation of finding out that Hearn had passed away in Tokyo in 1904, had been married to another woman, and had left Alethea nothing in his estate. Alethea’s response in the face of this “disaster” was to begin legal proceedings against Hearn’s estate. It was a scandal that a Great Man of Letters had been involved with a “negress,” so the newspapers were more than interested.

I based Alethea’s voice in the novel on these two documents, but what brought her full and present to me as a character was this act of standing up for her rights in the court of law and in the court of public opinion—the newspaper interview. In Alethea’s section of the novel, I imagined her giving this interview to the reporter, a young white woman, who’s hungry for scandal and readership (the actual article had no byline, so I felt free to imagine that the reporter could have been a woman). I honed in on Alethea’s desire to tell her story, not just in relationship to Hearn. Did I doom myself by attempting to write the “impossible,” as Professor Hartman calls it? Most likely.

So why did I do it? “Hunger,” as Professor Hartman so succinctly put it: “The loss of stories sharpens the hunger for them.” I’ve said elsewhere that you cannot know the power and significance of food until you understand hunger. The Sweetest Fruits is pitted with hunger (Oh goodness, did you see what I just did there? Pit, fruit, ah!) of the spirit and of the body. By that, I also mean my own hunger to know the stories of the women whom I had encountered. No matter how you may feel about Hearn at the end of the novel, you must acknowledge that without him, we would have not met Rosa, Alethea, and Setsu.

Setsu, unlike Rosa and Alethea, could read and write. Her language was Japanese. Hearn’s language was English. Toward the end of his years in Tokyo, he was able to write simple, childlike letters to Setsu but he never was fluent in Japanese. Hearn’s biographers, for the most part, characterized Setsu as illiterate in English. They rhapsodized about how Hearn communicated with her in a simple mixture of Japanese and English, a language that [they] called Hearn’s language. An invented language? A hybrid language? I love it, but I didn’t buy it for one moment that it was “his” invention and his alone. There must have been a co-creating, a co-innovation, especially since they were living in Japan, a country where Setsu clearly had the linguistic upper hand. That re-imagining of how their communication took place, how their language began, and how it deepened or didn’t during their years together provided me, as author, with such pleasure. To follow through with your varnish or unvarnish metaphor, first I had to strip away the characterization of ignorance. Setsu, then, could take on the characterization of creator and collaborator.

Setsu, like Elizabeth, published a book about Hearn. It’s entitled Reminiscences of Lafcadio Hearn, and the English translation was published in the United States in 1918. When I first read that translation, I noted the simple language, and I wondered if the translation was faithful in spirit to the original. Literary translations are their own creations, but the best ones respect the originals. I wondered if there was this respect shown to Setsu and her words by the two translators. I sensed that it was lacking.

When I was at the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial in Matsue, I found in their small bookshop a Japanese-language biography about Setsu. Full disclosure, I have no fluency in Japanese. I saw the book cover, which I remember had a photo of Setsu, and asked my companion, a Japanese professor and the literary translator for The Book of Salt, whether Setsu was, in fact, the subject matter. I then found an English translation of this biography once I returned to the U.S. The author, Hasegawa Yoji, had also included in the English edition a new translation—his translation—of Reminiscences. He was critical of the previous one and confirmed for me that there was an underlying disrespect and carelessness shown towards Setsu’s voice.

Hasegawa’s biography was a revelation in so many ways. Setsu came to life for me. She began to make sense to me. Her voice, measured but rippling under the surface with disappointment and anger, spoke up and I listened. It sounds like a séance? A ghost story? Writing historical fiction can be just that. But the writer is not conjuring the ghost. It’s the other way around. The writer is not bringing the ghost to life or giving her a new life. It’s the other way around.

bn

Your response addresses what was going to be my follow-up question—what are some pitfalls of Hartman’s “critical fabulation” and how did you address them? Having read the novel, I’m thinking of how slippery and risky the communication of people’s stories and voices can be—both within the “shorter” timeframe of bringing Setsu’s Reminiscences to translation in 1918 and the “longer” timeframe of these ghosts conjuring your writing of The Sweetest Fruits in the 2010s.

I’m thinking of Hua Hsu’s recent essay that spoke to the possibilities and limits of “representation” (or representazn) in culture as a “weak proxy for actual politics.” I’m also thinking about recent conversations about movies that have been touted as victories for representazn while being justifiably criticized for appropriation—Crazy Rich Asians and Always Be My Maybe. I don’t think the question is whether Awkwafina’s blaccent is a blaccent or Jenny’s dreads or Marcus rapping source from Black cultures, but how does one reconcile Asian American stories that have taken from and trampled on Black American culture?

Recent literary debates on #ownvoices also come to mind. When considering stories of a transnational scope like The Sweetest Fruits, it’s hard to imagine one author being singularly equipped to “authentically” represent all voices in this novel.

I imagine letting the ghosts speak requires a lot of work, a lot of precise channeling. How do you navigate this complexity?

MT

I think the words that resonated with me the most in Hartman’s essay are “inevitable failure.” Here’s the quote:

“The necessity of recounting Venus’s death is overshadowed by the inevitable failure of any attempt to represent her. I think that “this is a productive tension” [between necessity and failure] “and one unavoidable in narrating the lives of the subaltern, the dispossessed, and the enslaved.”

I think that is a clear-eyed way to think of the narrative project of the novel. I knew during those eight years—though I had not yet been introduced to the essay by Hartman—that I could fail by writing in the voices of Rosa, Alethea, and Setsu. I proceeded anyway, not out of hubris but out of the belief that THAT is one way of understanding what it means to be an artist. You take the risk, you risk the failure. You create nonetheless.

Of course, here’s the reality: If I “fail” Alethea, then I add insult to injury. I fail not only myself, as writer, but I would fail Alethea by adding to or by perpetuating racist stereotypes and caricatures.

Why do it then? Here’s the honest answer: I don’t think that writers choose their subjects. I think they choose us. I think they step out of history books, off the sidewalk, or from a near future, and they say, “Hey, fool, you’ll be writing this one!”

With that said, I don’t mean for my answer to serve as a shield or a deflection of responsibility. Nor would I ever use fiction as a shield or a deflection. You take the risk, you risk the failure. You take responsibility.

In the expanse of the imagination, stories belong to us all, but in the realities of publishing and the marketplace only a few of us emerge as storytellers and storywriters. The imagination is a borderless expanse, but American publishing is not. Who gets to make their living as author, who gets to be called expert, who gets tenure, who can pay the rent and health insurance, those are the questions that come to my mind when the debate about representation rages.

bn

Also, since the book’s called The Sweetest Fruits, what’s one of your favorite fruits?

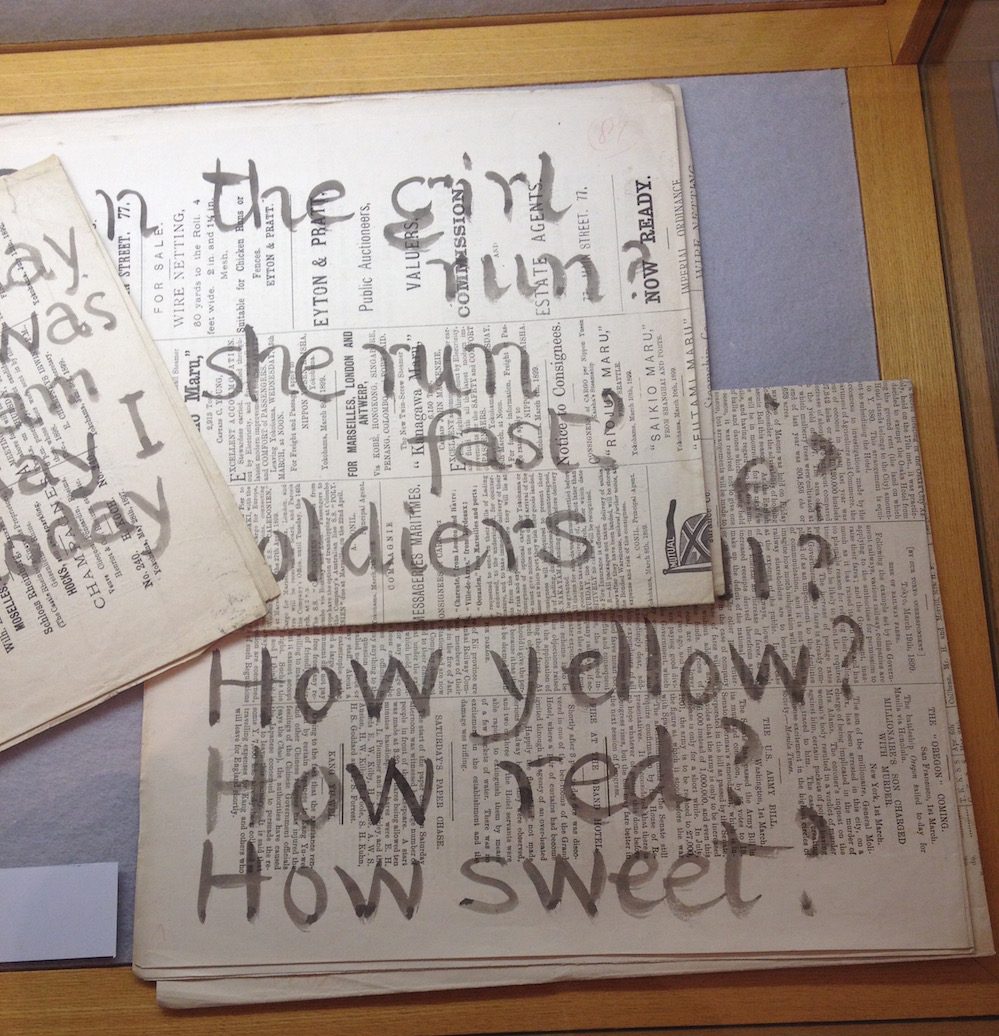

Image by Minnie Phan: black and white line-animation of a knife slicing a mangosteen, a seed of which grows back into the original mangosteen