Does the decades-old NYC tradition of community patrolling keep city streets safer?

June 3, 2021

Lily Deng, a Chinese American computer science student at Queens College, still remembers the visceral reaction that prompted her to begin patrolling. She had seen a news story about an elderly Asian woman who died after being attacked in a park, and the need to do something tangible unfurled within her. No amount of venting or online activism could touch the root of what had made her cry in the middle of the night.

Deng had already heard about Main Street Patrol—a volunteer group created to watch over the streets of Flushing. The patrol, she hoped, would give her a way to protect potential victims who resembled the faces she knew and loved from dinner parties and family reunions. Deng filled out an application and signed up for the group’s next available shift.

Main Street Patrol was created in February by the actress and activist Teresa Ting. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, fear and anger seeking culpability have been directed, sometimes violently, at Asian Americans. By late spring, the NYPD had received 35 reports of anti-Asian hate crimes: seven more than there were last year, and 32 more than in 2019. Nationally, the group Stop AAPI Hate received nearly 3,800 reports of anti-Asian incidents (a figure they believe to be underreported) between March 2020 and February 2021.

In response, Chinatowns in Oakland, San Francisco, and Manhattan have seen residents and allies come together to create community patrols, keeping a lookout for anything from a racial slur to an act of violence.

On an overcast Sunday in mid-April, Deng—who had recently been promoted from volunteer to team leader—drew her patrol away from the plaza where they had gathered and towards Main Street. Patrol Three, one of four Main Street Patrols working that day, spent hours tracing the same route, walking past dim sum restaurants with elaborate outdoor dining hutches and neon signs advertising sales of pork belly.

As they walked, Deng asked her fellow patrol members, Richie Luu and Sweta Vohra, which of the ‘5 Ds’ they would feel most comfortable handling. The 5 Ds—Distract, Delegate, Document, Delay, and Direct — are a reference to the teachings of Hollaback!, a bystander training organization, which volunteers are supposed to review before they begin patrolling. Much of what Main Street Patrol does is documentation. Volunteers have an airpod or corded headphone tucked snug into one ear that is synced with a walkie-talkie app on their phones. The app connects them to a central dispatcher in charge of monitoring the activity of each patrol group.

Deng and Vohra live in nearby neighborhoods in Queens, but Luu has lived in the area his whole life. “In five days,” he said, “it’ll be thirty years in Flushing.” His mother immigrated from Taiwan in the early 80s. As we walk, he points out long-standing Flushing institutions and laments the migration of all the good Taiwanese bakeries to Jersey.

“Attacks on Asians have been happening for a long time,” Luu says. “There have been people who reported assaults or harassment and the police just shrugged. So you have tall Asian guys in the supermarket just walking their moms around.” His mom has been asking him to accompany her to the grocery store for years.

There has been debate about the extent to which the level of violence is rising, whether the issue is simply getting mainstream attention for the first time. But safety, as it is experienced in one’s own neighborhood, is not simply determined by data. A statistic is not what makes a grandmother or granddaughter afraid to step outside her door; it cannot alter, let alone ameliorate, the fact that Asian Americans do not feel safe in the communities they have built.

What Luu does feel has changed is the visibility of the violence—and the recognition that it exists. “At least you have the internet to spread this stuff now,” he added. “Before, if you just talked about it, people would think you were crazy. People are more comfortable sharing now, one hundred percent. Five years ago, people would be too scared to say they were attacked. Now, everyone comes together as a community and says let’s talk about it. Aunties I know have no faith that the police will do anything, but they want to speak out to make things better for the next generation.”

The group passes an alley bordering a playground and Deng points out a spot where, during a previous shift, a thief had fled after stealing headphones from a sidewalk vendor. Her patrol had checked in with the vendor afterwards and asked if he wanted to file a police report, but the man had declined. “He didn’t think the police would be able to do anything,” Deng explained. But she added that he had seemed reassured by their asking. The idea that people on the street were looking out for him was not quite the same as justice, or retribution. But it was a reminder of a fact easily and ironically forgotten in a city of eight million people: He was not alone.

□ □ □ □ □

Community patrols are often lumped in with Neighborhood Watch Associations in the kinds of tony neighborhoods where the local police blotter suspiciously reports sightings of people of color doing ordinary things. In New York City, where ethnic enclaves have frequently found themselves both ignored and directly targeted by law enforcement, community patrols have existed in some form since at least the 1960s. In the late 60s and 70s, groups organized to escort the elderly around Harlem. In 1968, the Harlem Tenants League invited youth patrols to keep guard over public housing projects (the police, they said, were only hassling residents). In the late 80s, Black Muslim men in Bed-Stuy “with walkie-talkies and solemn stares” patrolled the streets in an effort to combat open-air drug trafficking.

Main Street Patrol is part of a long history of community patrolling in this nation and this city. Regardless of race, class, or creed, we come to believe that if we are not going to be protected, we must find a way to protect ourselves.

One of the flashiest examples of community patrolling in New York City is a group that flourished in the 1980s, as fear of crime spiked to skyscraper heights. Led by a Polish-Italian Brooklynite, the Guardian Angels comprised primarily Black and Latino youth from around the city. Unarmed, though informally trained in martial arts, the Angels began in 1979 with 60 volunteers, patrolling the 230-mile subway system.

“In calling upon self-reliance within poor communities of color, [the Guardian Angels] promoted a kind of ‘third way’ of managing public space and the rise in crime as an alternative to, and sometimes in opposition to, the police,” Reiko Hillyer, a historian of built environments at Lewis & Clark College, wrote about the group. The Angels were often hailed as heroes by subway riders and residents of color who had come to expect neglect at best and harassment at worst from law enforcement. Though the Angels’ prominence has receded over the years, they have recently been showing up in Flushing and Manhattan’s Chinatown in glints of flashy red jackets and berets.

Writing for the Gotham Center about the history of civilian anti-crime patrols, University of Nottingham history professor Joe Merton said that New York City in the 70s, “witnessed an astonishing proliferation of citizen-led crime prevention initiatives.” That rise was due in large part to the steep reduction in police manpower during the city’s fiscal nadir. According to Merton, “By the end of 1976, over one-third of New Yorkers reported their confidence in the police’s dependability as ‘zero.’”

The past year has seen another decline in public confidence in policing; last summer, trust in law enforcement hit a record low. The questions of how much to cooperate with the police and what a patrol’s interventions should look like have become especially trenchant as more of the nation has begun to rethink the efficacy of the carceral system and the ethics of working within it.

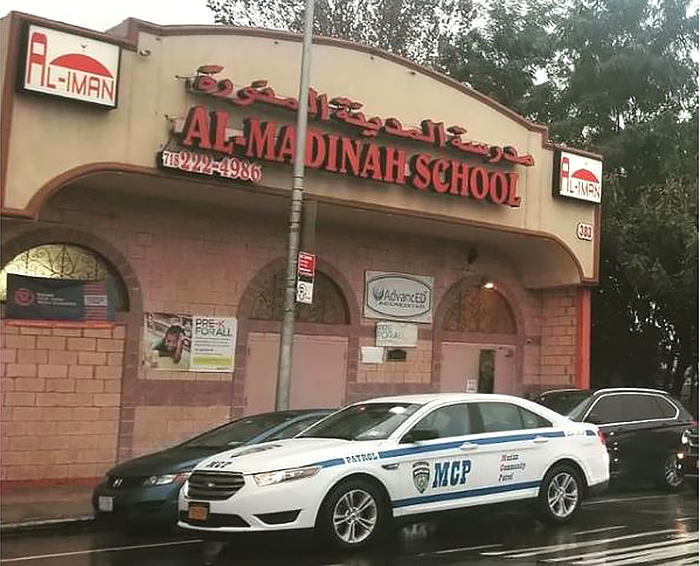

Many community patrols choose to work with the police. In 2014, members of the Brooklyn Asian Safety Patrol in Sunset Park would call the local police precinct if they witnessed a crime or suspicious activity. A member of the Muslim Community Patrol, whose volunteers watch over Islamic schools, mosques, and transportation hubs in Bay Ridge and Sunset Park, has said that the group serves as “the eyes and ears for the NYPD.” (The patrol is controversial within Brooklyn’s Muslim Communities: some have criticized the cooperation with an agency that has routinely harassed and surveilled them.)

The Shomrim, community patrols in Brooklyn’s Ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods, have chased down burglars, provided crowd control during processions of the Torah, and aided law enforcement in navigating the language barriers and social complexities of their communities. But non-Orthodox residents have called into question the groups’ close relationship with the NYPD (which has included an annual softball game in Borough Park), complaining that such camaraderie gives them outsized influence, particularly at the expense of Black and Hispanic residents. There have been numerous reports of Shomrim members assaulting Black men, and in 2013 a jury acquitted a man of over a dozen charges after deciding that the Shomrim had overstepped its authority in going after him. “The Shomrim can’t decide if they’re going to be judge, jury and executioner in the middle of the street,” an exasperated juror said after the trial.

To try and ensure that members adhere to its principles, Main Street Patrol has a vetting process for volunteers. Before Deng was accepted, she was invited to a group Zoom interview where she and a handful of others were asked a series of questions: if there had been previous instances where they had stepped in and helped someone; what would make a good patrol.

“It was a nice, free-flowing discussion—we were encouraged to answer so they can judge if we’re extremists or hardheaded,” Deng said. “It’s a good process to filter out any bad people.”

Ultimately, anyone with power has leverage to abuse it. That holds true for groups whose work is enmeshed within the existing law enforcement system and for those who work outside of it. Hillyer noted that police frequently expressed frustration that the Guardian Angels had no oversight and were bound by no laws. She found out that when restauranteurs in Times Square asked the Angels in their heyday to rout any ‘troublemakers’ who discouraged business, some residents complained that the group overstepped its bounds and harassed gay people and the homeless. “The biggest winners [of the Angels’ presence],” one resident said, “are the restaurant owners.” The Angels’ leader, Curtis Silwa, recently announced he would be running for mayor—as a Republican candidate.

□ □ □ □ □

Last year, the NYPD announced the creation of an Asian Hate Crime Task Force—the first such group the department has created concerning crimes that target a specific race. Luu believes that in an ideal world, the patrol would be able to cooperate with the police to make the streets safer, but he doesn’t think either group has the necessary resources. Karlin Chan, the creator of Chinatown Block Watch in Manhattan, has also said that cooperation with the police—while not the only or even the driving-heart solution—seems to make the most sense. “If you report, they’ll have the numbers, and if they have the numbers, they’ll allocate the resources,” he told reporter Eveline Chao.

But others in the community see no reason to applaud or cooperate with the Task Force. The Asian American Feminist Collective released a statement condemning its creation due to the NYPD’s “long history of perpetrating violence within Asian communities.” They recounted physical acts of violence, harassment of low-wage workers, deportation measures, and evictions aided or perpetrated by the police against the people most in need of aid.

”Street patrols are in line with conversations about de-escalation tactics to deal with stuff like this rather than cops being first responders,” Sweta Vohra said. The April afternoon was her first time out with Main Street Patrol; she had heard about community patrolling in Oakland and looked to see if there was anything similar going on in Queens.

Main Street Patrol has tried to draw a clear line between themselves and law enforcement. The group’s FAQ insists: “We do not work with law enforcement, save for if our documentation can help find and apprehend an individual that has committed a hate crime.”

During the time I spent with the group, one patrol took down the license plate information of a group that had robbed a store and sent it to the police.

A case is compelling for something more in line with Jane Jacobs’ idea of “eyes on the street,” which the famous urbanist coined to evoke bustling public spaces and people who cared about what went on in them. Vohra explained that she had come out to patrol because she “had seen the hate crimes and wanted to put my body somewhere it would be useful.” The presence of real people who care about a neighborhood—instead of police officers or CCTVs—could help to create a safer community.

The effectiveness of community patrolling on crime or violence is difficult to measure, and Main Street Patrol does not disclose the number of incidents they encounter. And, just as the power that patrols cultivate can be abused, their lack of institutional standing or firepower presents a particular hamstring. Most patrols are unarmed, unable to do much more than attempt to scare a perpetrator off through strength in numbers or document virulence online. Weapons tip the scales into the territory of vigilantes and militias. For groups who wish to operate within the bounds of the law, there is a limit to what can be accomplished with a loudspeaker and a smartphone.

Some time ago, when a patrol member began recording two men who were heard making racist and threatening remarks against an older man, the men knocked the phone out of the patroller’s hand and fled. Before Teresa Ting sent the patrol groups out, she reminded volunteers to document incidents only if they were sure they could do so safely.

□ □ □ □ □

Pat Sharkey, a sociologist at Princeton who studies policing and urban violence, wrote last summer that “residents and local organizations can indeed ‘police’ their own neighborhoods and control violence—in a way that builds stronger communities,” but added “this isn’t about citizen watch groups.” Instead, he stressed the importance of grassroots community programs, like after-school activities and summer jobs programs, turning abandoned lots into green spaces, and street outreach workers intervening to de-escalate conflicts.

Luu would like to see Main Street Patrol expand beyond its citizen-watch-group origins. “Realistically, I think once COVID comes down, the next issue is dealing with the follow-up from right now,” he said. “You can see these volunteer groups forming in formative months when you see hate crimes happening, and you ask yourself: is it going to stick around next year when there are no more hate crimes, or when you don’t see elderly people getting assaulted?”

It’s one thing, he said, to try and protect elders from bodily harm, or death. But he wants to see the community rally around their lives, and reckon with the poverty and loneliness that causes older members of the population to spend so much time on the streets. “I think the right approach on this is not just to call out hate crimes or elderly people getting shoved around, but to engage with the community,” Luu said.

In May, Main Street Patrol launched a food donation drive in partnership with the Flushing Community Fridge aiming to provide access to surplus meals, fresh produce and pantry items to anyone in need. “I think that’s a great way to branch out from the darker parts of our community and uplift those in need,” Luu said.

When Merton was looking into the history of patrols in the city, he found out that the ones in poorer neighborhoods were difficult to sustain. Communities already short on time and resources struggled to find an abundance of each: a reason why the most vulnerable people in a society should not be left to safeguard themselves.

The fact that they are is no accident. Reiko Hillyer discovered that funding for community policing measures favors organizations in white communities like Girl Scouts troops and 4-H clubs rather than initiatives in neighborhoods of color. “These selective funding practices,” she wrote, “reflected a particular nervousness about empowering minority groups.” But initiatives like Main Street Patrol, which include both local community members and allies, may be one ostensible solution to the lack of government support in neighborhoods with fewer resources.

Luu said Main Street Patrol has given him the chance to see and engage with Flushing as more than just a bystander. It has offered “a palpable opportunity” to “find anyone who feels like they’re being harassed, or someone who needs translation”—to actively participate in the community where he has lived his entire life.

The palpable nature of patrolling is also what appeals to Deng. She had tried donating, petitioning and attending rallies. Nothing else, she said, “was the same as going out there and putting in time to look after a community.”

There is an irony in the fact that patrolling is a tangible activity with intangible results; it is nearly impossible to measure outright the effect that Main Street Patrol is having in Flushing. Patrol members can only hope that each small action they take—speaking to a street vendor, checking in on a woman shrugging off unwanted advances of a man, monitoring a person yelling in the street–will add up in the eyes of the community. Ultimately, what gets volunteers through the three-hours shifts each weekend may be the possibility of a more internal balm.

“It’s OK to be frustrated, but I want to make an impact,” Deng said. “For me, patrolling is a gateway to interact with the outside world. And the more time I spend doing it, I think we’re not just protecting the community, but also each other.”