He collected the past in amber, often describing war memorials as beautiful. He called himself a gardener.

August 28, 2020

“It’s not the same,” Lamai’s husband explained, when he told her about paying for sex. “Because there are things you can do with a prostitute that you can’t do with a wife.”

She asked what things.

Nik made her a list in his childish handwriting.

“The sex could be better,” he told her.

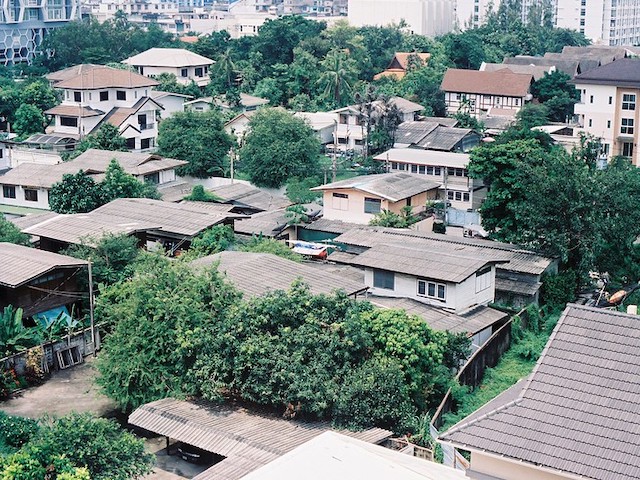

Better. The word Lamai returned to when she left her husband and Pinky, a friend’s friend who owned rental townhouses, put her up. Stooped, Pinky was surveying an herb garden when Lamai arrived. The tufty greens grew in neat squares where the stone tiles had been prized up to reveal swamp earth—wet and wormy, and the plants had taken.

“Only farangs would try to grow food in this khlong mud. It’s their overconfidence,” Pinky said.

Lamai remembered being told that in the trenches, in the First World War, the soldiers had kept gardens. They used artillery shells as flowerpots. Celery had flourished in the damp passages. The bombardments had dispersed nitrogen, a fertilizer, across no man’s land.

Nik had told her that. He collected the past in amber, often describing war memorials as beautiful. He called himself a gardener.

“I was fooled,” Pinky said, unlocking the door, “by farang bravado. I believed that foreigners would make better tenants than Thais. Multinational companies forked out on my extravagant rents until this catastrophe. This collapse. Ninety-seven was supposed to be my year, but ‘Capital flight,’ the newspapers say. The farang families have fucked off, too.”

Pinky led Lamai first into the kitchen.

“The people that lived here drove their old, gold Benz to the airport and left a number, mine, on the dash, which the police eventually called. That’s how I knew they were gone.”

She swung open the double doors of the pantry. Everything was imported: Lucky Charms, Pop Tarts, Jack Link’s Meat Snacks. The milk in the fridge was still good, and the freezer drawer was full of bagels.

“Of course, I won’t charge you rent. You can’t afford it. But I want you to sort through all the shit the Americans left behind. Sleep in their clothes, burn off their candles, eat up their life. That’s what I ask.”

They went up to the children’s room. Helium balloons wrinkled in a corner and there was an artificial, cloying smell that reminded Lamai of birthday cake, the taste of sprinkles. A comet, suspiciously shit-colored, streaked across the wall beside one bed.

Pinky took the strap of Lamai’s bag and hefted it. “What’ve you got in here? Box dye? Booze? I won’t have a divorcee stereotype squatting in my townhouse. I was once married, too. I know all the symptoms. I always imagine my rentals as happy places, and sadness is like pet piss in the carpet. Once it seeps in, every subsequent tenant has to live with it.”

The walls of the stairwell showed grey palm prints.

In the parent’s bedroom, a pair of handcuffs were attached to a bedpost. Pinky shook the chain. “The metal links are rutting my wood. See if you can find a key on your side.”

Lamai searched in the bedside drawer. There was a coiled tube of KY jelly and “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.”

“No.”

Well, that was the tour. Pinky took them back outside.

“When I return, I don’t want to see any proof of that former life. I want it new. New and empty.” Pinky tore a sprig from the herb patch and ground it between her fingers, her other hand jangling the keys, as if deciding whether to hand them to Lamai.

“Quiet, aren’t you?” Pinky leaned in. “Your silence won’t save you. You look like you’re in shock. It’s not a bad pallor. Or were you born this way? A little anemic. A little wan. That’s ‘in’ nowadays.”

She sniffed her hand. “What is this?”

“Thyme,” Lamai said. Then she lifted one of the heavy tiles and dropped it onto the thyme, crushing the plants.

The jolt made Pinky step back. She sucked her lips, then held out the keys.

“In you go.”