Toronto-based graphic novelist Elisha Lim talks about the people behind their latest book 100 Crushes, their Singaporean-Catholic aversion to gluttony, and what jealousy is really about.

December 11, 2014

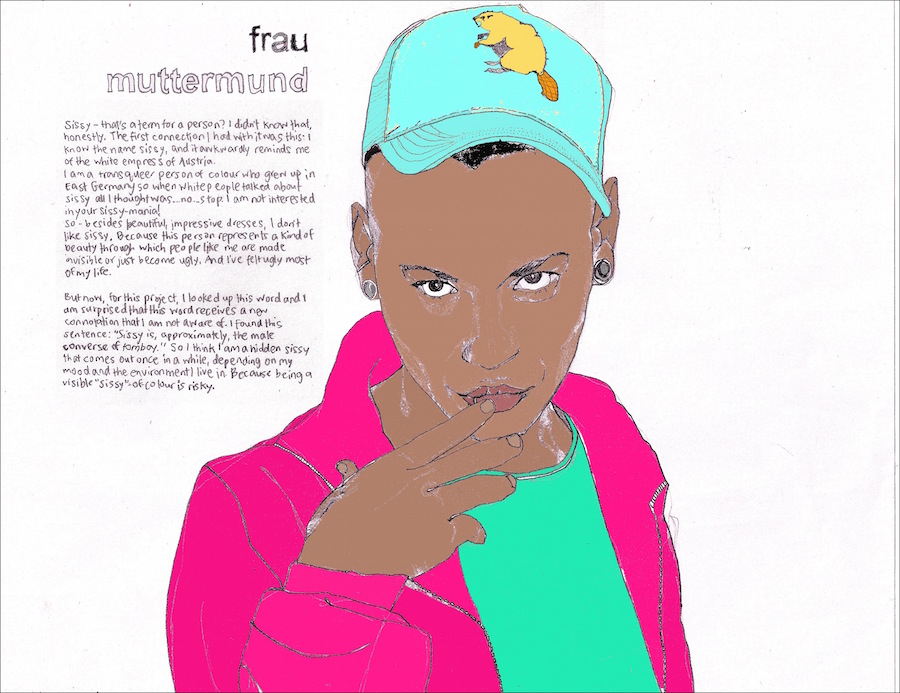

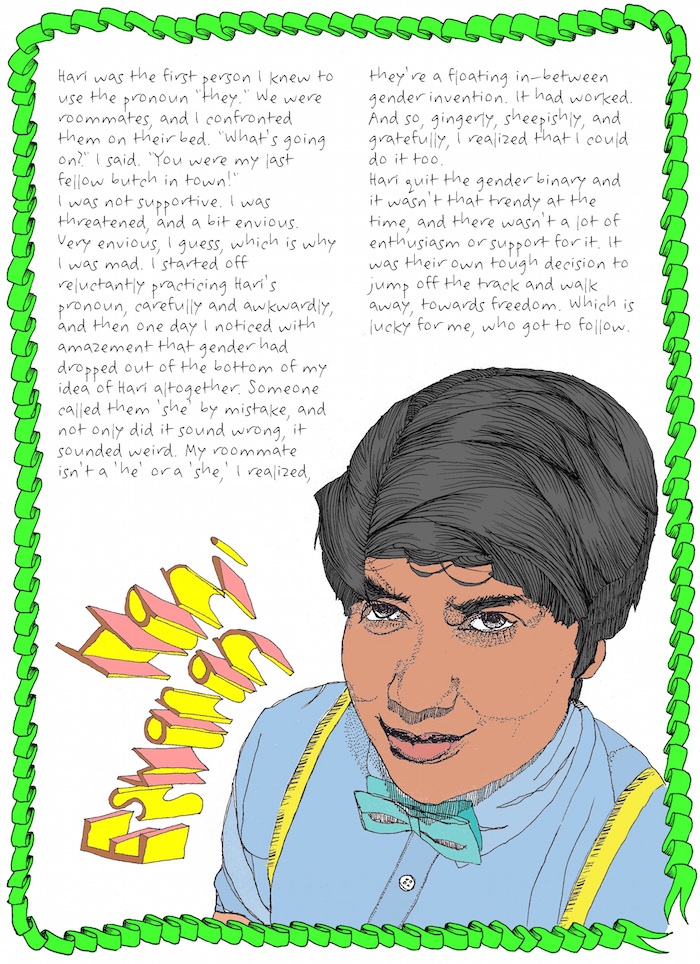

Elisha Lim is a writer, filmmaker, artist and art champion. Their multi-disciplinary approach to creative projects mirrors an implausibly diverse ideology that they embody through self and community. 100 Crushes, out from Koyama Press, is Elisha’s newly published collection of stories and observations on queer and other non-binary (race, class, geography) systems. The net effect of these stories is a world depicted in beautiful portraiture and heartbreaking personal growth. Here, we talk about how to get to the community of their dreams. The short answer: together.

Elisha Lim: I’m kind of excited to be talking in the context of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop because I feel like the audience that I’ve had has been afraid to talk about race-related issues; queer identity has been my central issue.

Anne Ishii: I think you’re touching on something interesting: that “Asian” and “sexuality” are mutually exclusive. If you’re going to talk about one thing, how do you talk about the other? Do you feel like you get more questions about queer identity than Asian identity?

People have talked about how important it is that we’re addressing a range of queer identities, but that’s not really where my heart is… I’m talking about angry, anti-racism.

(hearty laughter)

Okay, lets talk about angry, anti-racism then. What do you think of Asian American identity polemics as they trend in North America, given the heterogeneous Asian experiences of some of your subjects and selves?

The stigmas attached to Asian identity affect us as much as the next person. I don’t know if “struggle” is the right word to describe this, maybe it’s more “aggravation.” I’m excited about how Asian artists are coming together and talking. That impulse fights the really bland idea of Asians submissively assimilating into the model minority, supporting white CEOs, and “tiger moms” who want to get their kids into Ivy Leagues. It’s frustrating because the stigma hides the strong Asian North American history of activism and political engagement. And that’s what I want to celebrate.

I’m reminded of Yuri Kochiyama, who just passed away earlier this year. Not a lot of people in the Asian community were aware of who she was. Interestingly you corrected yourself in the middle of a sentence. You said, “Oh it’s not really a struggle. It’s more like aggravation,” but many Asian Americans feel this frustration—that their issues aren’t strong enough to turn into a battle cry, right? We’re not getting shot defenseless in the street… it’s something else completely. I hesitate to say even this much because I do not pretend that stereotypes are comparable to criminalization, but how do you agitate people who are mildly irritated and turn it into a rallying cause?

I am really grateful for my sister. She was one of the deputy editors of Racialicious and she was like a pitchfork into the heart of white supremacy. It might have simmered from her to me. But she totally raised me. We’re like Ernie and Bert. She told me about Andrea Smith’s “Heteropatriarchy and The Three Pillars of White Supremacy,” and what North Americans are doing with the legacy of slavery, how Native North Americans are dealing with genocide and, for example, as Asians, the violence of Orientalism is of a different form, but it gives us the empathy to understand and relate to the violence of white supremacy. We see the way it dehumanizes white people as well as Black and Native people. We see a reason to dismantle it and fight it in solidarity.

In your writing, you introduce and cite leaders of other justice movements. You contextualize what they’re saying through your interpretation, but you don’t reproduce their opinion wholesale through your own voice. I don’t know if you have an opinion about that, but it seems that you’re very deliberate when you quote people in your book.

I actually have quotas. A lot of this book comes from comic strips I’ve put together over the years to sell as pinup calendars because I thought that was a really good way to share a message—to have it up for an entire year. My quota in the first year, 2010, was to feature a maximum of one white person in the calendar, and from then on there were no white people. It’s very deliberate. I want to not depend completely on people’s testimonials though. And to tell you the truth, I’m really nervous about my next project because it’s not going to be directly political, although it will be in its ultimate message. I’m wondering if reviewers are going to say, “Oh more queer material…” I’d be so sad. However, if it’s, “Ooh this is a stinging anti-racist critique,” I’ll still be like, “Touchdown!”

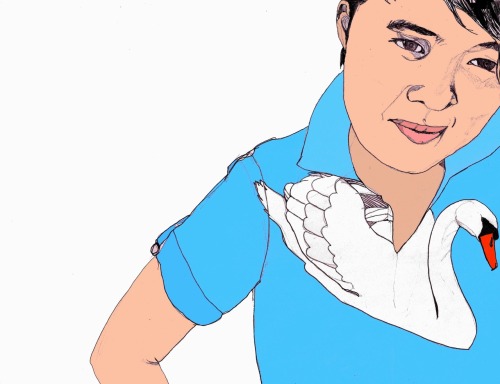

From Elisha Lim’s 100 Crushes. Click to enlarge.

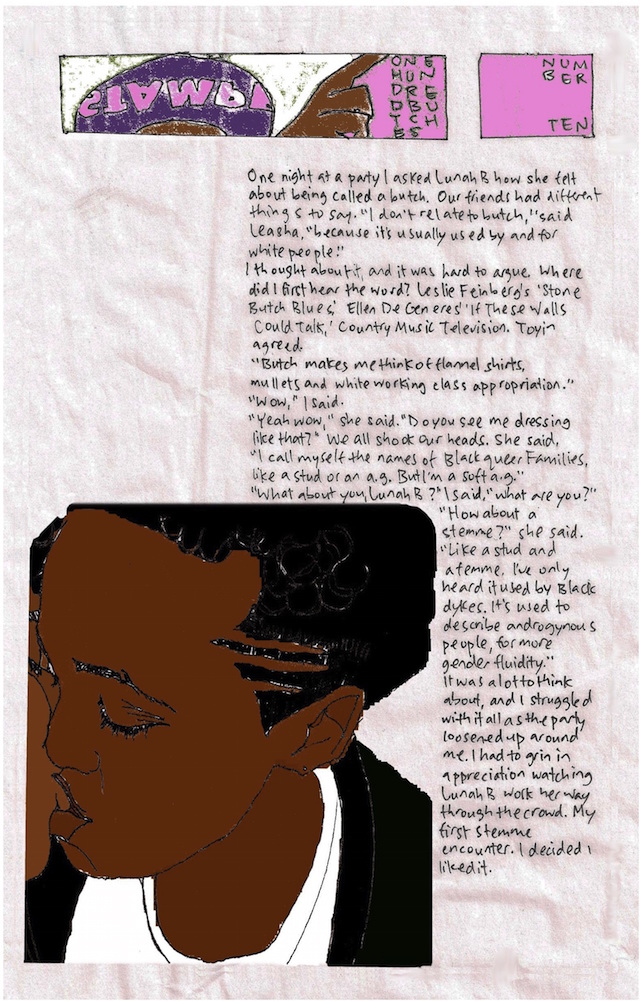

From Elisha Lim’s 100 Crushes. Click to enlarge.

I don’t doubt it’ll be stinging, but what is your next book? What are you working on?

I’m working on a book that is in the story-draft stage now, but I have no idea how I would draw it. I’m thinking of three stories in my life, all personal stories, when I was really angry. I still carry a grudge, and I want to use these stories to conceptualize the process of forgiveness and to think about what’s at stake in forgiving. How my anger is part of my agenda. How it has become a crucial part of my identity. Why I hang on to this grudge. You know, it really defines me as an activist. And why letting go of it feels so taboo and so risky.

That’s interesting. Can you elaborate on that? How is grudge-holding taboo?

No, grudge-holding is good! Forgiveness is taboo!

Wow. Give me an example.

So I had this very fraught relationship with a white partner and it was this classic dynamic in the household where we were both anti-racist activists but they were getting hired and paid for that work and I was not. We started to have a really large material and financial difference in the house, in terms of what we could afford. And there was a power balance because of that income disparity. I was especially jealous and it’s something I’m a bit ashamed to admit, but to be honest that kind of anger and jealousy and pride is part of what fuels my activism. And forgiving this person—to genuinely forgive this person—would require a dismantling of all the individualism and almost the consumerist capitalism of my style of activism. I’m entitled to certain respect and rights and I am cashing it in for this sick thing—social status. It’s really kind of corrupt but, I mean, I’m not going to stop. And the idea of forgiving this person, to me, seems almost self-destructive and scary because then what kind of activist am I? What about my trophies and my skulls, you know? And that’s perverse. I’m pursuing this activism out of a complete maniacal, pathological image. I feel like holding a grudge makes me a more pure, better activist. And forgiving would be repugnant and disgusting to my community.

Oh my god… That was just a lot of honesty. I got chills thinking of this idea of grudge-holding as your pure core. Using jealousy or anger as fuel in a productive way is really interesting. Technically, envy is a mortal sin, right up there with murder. In 100 Crushes, “Jealousy” was such a blistering piece because your making peace with jealousy wasn’t about forgiveness, it was something else entirely. That chapter was about your thoughts on other people, but you’re depicting only yourself, not the subjects of your jealousy. When you were writing this story what were you thinking? How was this going to end?

Jealousy is one of those things that reveals vestibules of you. It’s an experience that said much more about myself. In the first panel, of me in all the different relationships, I could think of so many times in my life when I have been adored. It’s such a wonderful thing. And it’s the last thing that I pay attention to when I’m jealous. I’m insatiable! I demand to be loved! But there are ways I have been the unfaithful one and I have been deliberately cruel; deliberately greedy or narcissistic in my own behavior and that’s probably why I’m jealous. I’m very vain and I enjoy the explicit attention I get sometimes. When I talk about jealousy I’m portraying myself as innocent and that is the last thing that I am.

Every single women that I was threatened by was actually based on either my mother or my sister. They were complete fantasies of my imagination. They were archetypes of what I thought was the most beautiful way any human can be. My mom when I was little—when I worshipped her.

How is the mother of your adulthood different?

We start to see them as fallible adults. The last panel in the book has a picture of me on her knee on my second birthday and she’s in her virginal white dress with these red, red lips. That depiction is the essence of my mother in my mind—the most pure, most perfect version of femininity.

That’s a pretty bold place to go… I’m thinking, “It’s so Freudian,” which is problematic, but is that something you’ve thought a lot about? How family is a sexual archetype?

No, I love that. I think it’s truly interesting. In my older life I’m so much more connected with my masculine side and in some ways I know that I’ve abandoned the feminine side of my family. But I have this self-sexist mechanic in my head where when I imagine the people I envy most, their perfection is feminine and that perfection stems from a femininity that I have departed from in my adult life. That femininity is what raised me.

Let’s talk about your jealousy and the idea of open relationships versus cheating. You used the word “unfaithful” earlier, which is such an interesting word. I read somewhere how prevalence of open relationships in the straight community, for lack of a better word, has been directly influenced by the visibility of queer relationships. It seems to suggest that sexuality is not limited to how one identifies themselves or who they prefer, but is also about the dynamic of the relationship. Is that something that figures at all into your thoughts on your sexual identity or preferred gender identification?

I struggle with that identity because there’s so much of it that I don’t really do. I was thinking of possibly producing, not a book, but just a little whatever about monogamy, because I’d like to say that I embrace radical, subversive, queer monogamy. And if you don’t want to pursue monogamy with me… OUT! I had a jacket and I screenprinted the word monogamy across the back… But you know what? I’d be really curious to ask about how this fits into the ways that we’re socialized as Asians. I know that there are plenty of proud exhibitionist Asian queers. But I think it may be a part of my growing up in Singapore. It just doesn’t feel appropriate to me. Unfortunately that affects my judgement and feelings about BDSM and sex parties, about conversations and workshops about sex. Even though that’s central to queer organizing, a lot of times I’d rather stay home.

I’m right there with you, in the same exact boat… It’s one thing to talk about sex and it’s one thing to be a little bit scared of sex, but to talk about how sex is scary is another thing entirely. I wonder if more than anything you don’t want to come across as a pussycat. What do you think about sexual courage?

Interesting. I was saying, “Lets get it out there that I’m vanilla.” I grew up in Singapore and I was very devout to the Catholic church—to a Chinese Catholic church. My family comes from this part of Guangdong province that was intensely converted to Catholicism. My grandma has a certificate from the Pope for her service to the church. It’s complicated to articulate but it’s not that I have shame around sex. It’s that I would hate to be gluttonous or too indulgent. Indulgence is just the worst thing you can embody. To publicly discuss having an appetite… I avoid it so much that I dislike it in others. Appetite should never be admitted.

That’s a good pull quote: “Appetite should never be admitted.”

You’re not supposed to have an appetite! I’m sure that’s a combo of Catholic and Asian upbringing or something.

What resounds the most in what you’re saying is the distinction between internalized and externalized indulgence.

Also, something about entitlement? I am so enamored of the cultural values I grew up with in Singapore, where collective effort was everything. Everyone submits to the collective effort and it’s all about service, but service isn’t a sacrifice. Service is satisfying. Service is what gives you a sense of accomplishment at the end of the day. It’s an idea that I can’t shake even though it doesn’t work for me in North America. If I can’t contribute to anything, it turns me into a sucker and a loser, but it’s really what I love and it feels like that’s completely the opposite of someone saying publicly, “I want my appetite to be served. I want the social stage to serve me.” I associate that with entitled white individualism. I’m not proud of this. I know that people should do what they want.

This ties into a question I wanted to ask. What do you think of independent comics? For a while there was this white navel gazing story everyone told, with all due respect to the people who write that kind of graphic novel or memoir, because it’s not bad. Yours is quite striking in that it’s almost universally about other people.

I made myself laugh a lot with this comic strip that I did years ago. It was this claymation of my first impressions of North American subcultures when I moved here as a 17 year old. And I couldn’t get over them. My friends felt a big sense of duty to initiate me as quickly as possible to North American subcultures. They took me to indie rock shows and took me second-hand shopping. I mean, outwardly, I was probably like, “Please teach me. Just put me in the outfit. Tell me what to say,” but in my head I was thinking, “This is just the stupidest thing I’ve ever seen. This is bullshit!”

Do you have a community of comic artists? Or is your community less about comics necessarily? Do you feel like you have a caucus of peers?

Yeah, absolutely. In Toronto we’re super proud of having worked hard on developing a community of queer people of color. Although now we’ve got new lingo. Nowadays we call ourselves Bipoc’s!

Bipoc’s?

Yeah, it sounds like a disease! It stands for “Black, Indigenous, People Of Color.” It’s a way of recognizing the ways that people-of-color coalitions have failed black and indigenous people in the past, but…. we’re BIPOC queers! That is absolutely what I would call my community. And there are performance artists in my community as well—people involved in the everyday activism that I’m interested in.

I’d like to go back to an issue we touched on earlier—about feminine archetypes and your mother and sister, and how you feel you’ve crept away from your feminine identity. What about your masculine archetype? Who or what is that? Or does that even figure, given what you said about using the “they” pronoun?

I’ve really been inspired by different indigenous descriptions of gender. You know I’m kind of appropriating, but in communities in Indonesia, closer to my hometown, there have been traditionally or historically a variety of genders, somewhere around four or five assignations. I think that if I were a gender it definitely wouldn’t be male. It’s definitely not female. And so I think it’s not so much that I have masculine role models but that I just really crave alternate role models. My great aunt, she’s what you might call a butch. And she was a nun. She was very dedicated to this largely feminine occupation, but was never feminine in any way. She’s sort of my role model in ways. I think that she would also be someone in the third or fourth category. I wanted to ask you, if you relate to that at all? If you know any people in your life that are like that.

I’ll be totally honest. I want to talk about the masculine and feminine archetypes precisely because of this question of pronouns. I’ve found that words like “she” and “lesbian” are not popular anymore. Maybe it’s a generational thing, certainly compared to me. Even in college it was really important for women to gain visibility and now it’s like, well let’s just eschew with that entirely. I feel like it’s at the expense of a lot of real problems; sometimes really basic sexism 101 happens that’s brushed under the “they” polemic.

Yeah, I think that what you’re bringing up is really important. One of the ways there’s potential for the transgender movement to do more harm than good is when it is sexist and very often, now, when we talk about trans people we are not talking about transwomen. We’re talking about transmen. It’s just a new celebration of masculinity. White masculinity. It’s problematic when this movement just becomes a reiteration of the same sexism. And so that’s why I would say as a transperson, it’s so important that the leadership comes from transwomen. I see them dealing with the most violence of any of us gender questioning people. And the most oppression in terms of employment, housing, health.

In some ways the history of the word “lesbian” has failed us as a community because it has excluded transwomen. Lesbian bars would have signs up that said, “no transwomen allowed.” I try to move away from that term and use something that’s more inclusive of transwomen. I think it’s true that male is considered neutral because it’s the superior gender. And so if you’re going to go by “they” we’re going to assume you mean male. And that’s just reinforcing the idea that neutral gender means superior to female. But one of my transwomen friends Kit decided, you know I’ve had enough. Even though ‘they’ describes me better I’m going to go by ‘she’ because I want to make this statement. That was such a humbling thing to read… just feeling that this was causing more damage to transwomen than good. I still feel that not using the pronoun ‘she,’ for myself, feels really good but I think it’s so important to prioritize the voices of transwomen, of women. We have to constantly question the sexual basis of our society, all the time, as much as possible.

The nice thing about 100 Crushes is its cumulative effect. It’s so broad and it’s not just one story. It introduces so many people but creates one world. I like the idea that activism is about, I don’t even know what the word is, like a communal balance almost.

This is an Asian value! It’s what this is all about.