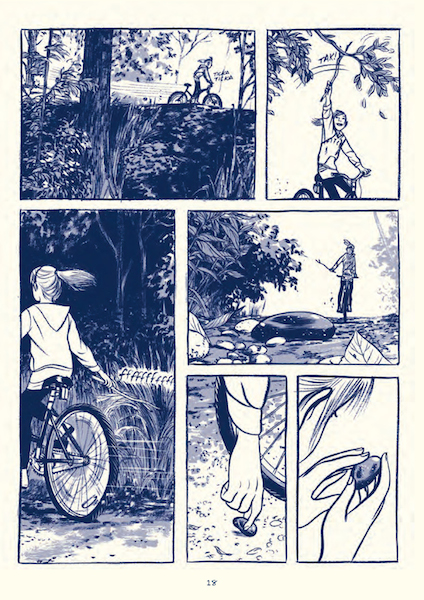

The 2015 Caldecott Honor-winning artist talks about adoption, race, and visibility in the coming-of-age graphic novel This One Summer.

February 12, 2015

AAWW board member and resident comics expert Anne Ishii is back with the second half of her interview with Jillian Tamaki. Read Part I here.

Jillian Tamaki is the illustrator-half of the graphic novelist dyad behind the critically acclaimed Skim and the unparalleled This One Summer, which debuted last May. The duo includes Jillian’s cousin, writer/performer Mariko Tamaki. Since running the first part of our interview with Jillian last October, This One Summer was awarded the Caldecott Honor, making it the first graphic novel in the institution’s history to be commended with the distinction. We are running Part II of our interview with Jillian to congratulate her, along with Mariko Tamaki. At the time of our conversation, social media was scrambling for responses to a couple political issues big in social media—Ta-Nehisi Coates “The Case for Reparations” at the Atlantic and hashtag calls to #CancelColbert after a racialized tweet from the show host’s account.

Jillian Tamaki: My great grandfather came to Canada when he was a kid, so they’re like super Canadian. They were interned and all their property was taken away. But my grandfather did not want reparations—he thought that was really insulting; that you would give us some thousand dollars or whatever and that’s your “sorry” and you can feel absolved. They all became lawyers because that’s what you do, you hyper-assimilate back into the culture and say: I’m more Canadian than all of you. And now my dad, he doesn’t know anything about Japan anymore. He doesn’t speak the language; he doesn’t want to go there. It doesn’t bother him. It doesn’t make him feel uncomfortable that he knows nothing about the language or the food. That got stripped away partially because they assimilated so aggressively. But it is kind of sad that I have like no connection whatsoever.

Anne Ishii: Is that something that comes up at all in your career?

It came up a lot with Skim—people want to pin a story on you and tie up the narrative and make you a stand-in. I mean race was touched on in that story but it was almost as touched on as being gay was. I don’t blame people, because if you’re writing a story people want some sort of narrative which is natural. But that’s not a mission statement to say that I am talking for all Japanese Canadians.

That’s a pretty North American thing to do though: assume an author’s identity is tied into the fiction they’ve written.

Right, that’s like what happened to Hiromi Goto. She’s a Canadian author and her first work was called the Chorus of Mushrooms. It was a Japanese Canadian story and she had gotten a lot of acclaim for this first novel but some old guy said, “Oh so you’ve written your Japanese Canadian story.” Like you have your one, the one book where you explore your race explicitly. Like what? That’s super strange that you would think that won’t be in all my stories, that now it’s time to “branch off” or write something more sophisticated.

Or that something more sophisticated means you can’t talk about a person’s race.

But there’s multiple things to talk about! My grandfather, before he died, wrote short vignettes, basically childhood stories, about his life in British Columbia before the war. He didn’t go to a camp—he went to university—but his family was interned. There’s nothing about wartime in the stories but the war is in there because it’s totally foreshadowed by their life, before all their stuff was confiscated. So that’s an interesting viewpoint that’s not like Joy Kogawa’s Obasan… which is a really important book. But I want to find the specificity in whatever character or whatever setting I’ve depicted, so it’s not some broad stand-in for any one race’s experiences. That’s just too heavy a burden, you know? It’s a heavy enough burden to take someone’s story, no matter who it is, and to try to adapt them.

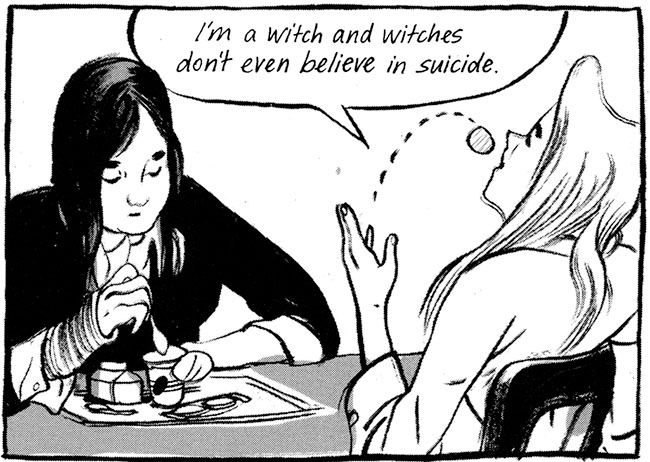

You portray race in a way that’s implicit and not explicit—for example, Windy (in This One Summer) is adopted… It’s a fascinating thing to look at adoption as a vehicle for this discussion.

Mariko was working at a parenting network when she was writing this work so she was dealing with a lot of gay parents and adopted kids; adoption was in her world. That’s why I tried to make Windy racially ambiguous—she doesn’t look completely white. Rose is a quarter Japanese, because her dad is half. But she’s blond, she has blue eyes. It brought up these questions after Skim: How are you going to spin the narrative now that these characters are not Asian American in an outwardly way? It was a little bit of a response (to Skim) because if this had been our first book I probably would have made her more Asian looking.

I think status quo is a good reason to stick a person of color in any book.

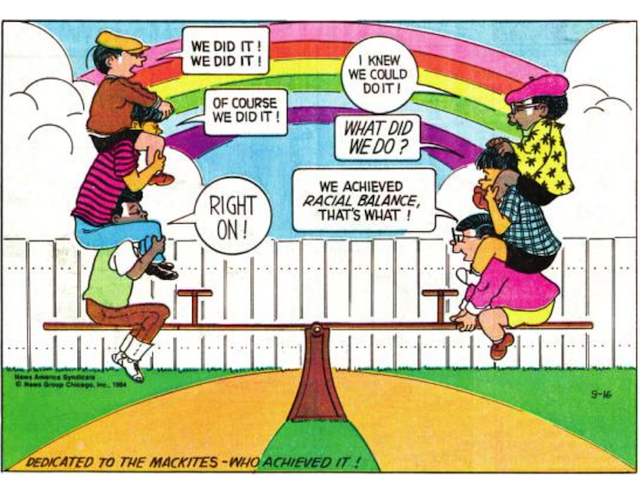

I remember when I started illustration and talked to a professional illustrator who told us, “One really good trick for getting around diversity is to make people purple or blue, or to color the whole picture so that you won’t have that discussion about whether you drew a black person or an Asian person,” which is really annoying: to just populate this weird stock photo of the comically diverse picture. I totally get why that person said it, but there is actually something powerful about visibility. I think there’s something eye-rolly about heavy-handed visibility. Like this is the point of the story where I empathize with you because we both have black hair.

Do you get a lot of that—of Asians saying, ‘Can’t you just spell it out?’

No, maybe if people wanted that from it. If they wanted a bigger thesis as to why Skim is bullied, I’m fine with you making that connection on their own but don’t assume I put that there purposefully. That’s why I put an Asian person in the mean girl group too because certain Asian teenage girls are also going to be bitches.

Yeah, absolutely.

Where I grew up in Calgary there was one other Asian girl, and she was Korean. Until I moved out to Ontario I didn’t know that Asian American or Asian Canadian was a thing. I didn’t know what all the stereotypical Asian Canadian things were, like I didn’t know what bubble tea was. It was so insane that there was this group I didn’t even know existed because there wasn’t that population there.

I still remember the first time that an Asian kid from Vancouver transferred to my high school in Los Angeles and I just remember the utter shock he went through. Because my school was 70 percent Asian and he was just like “low riders, bubble tea, what?”

I was exactly the same.

Everything has a context, right?

That’s where I feel like the social justice thing can get kind of out of hand a little bit. Context is important.

Which kind of goes back to that weird invisible line between (sexism in) superhero comics versus in indie comics. There’s that point where you don’t want to cross that line. Like, let someone else deal with it.

You can only have so much outrage at so many things in your life. That’s not been the thing I choose to be outraged by. I don’t want to add to the echo chamber. But I mean—I’m always glad that there are people who get really mad. Because nothing gets done if people don’t fucking complain. I’m really glad that there are crazy PETA protestors and I’m really glad that there are people that are intercepting whaling ships. I’m not doing it, but if everyone was like me the world would be worse, because we’re really complacent now.

Well I think you’re very aware of your platform, so if you’re fighting something like illegal whaling, then you need to do something extreme like hijack a ship. But if you’re talking about social decorum, then it’s a little bit different. So then a comic book or graphic novel makes sense to discuss these issues. Like twitter hashtag activism…

Which drives me nuts.

It’s fascinating, and I think it’s important but ultimately—

I think it’s illusionary. I feel like a lot of that stuff is useful up to a point. I’m glad that the word privilege has had this ballooning effect in the last few years through the Internet. I’ve seen it more on Tumblr while reading the really heartfelt and angry words of mostly young people. I need to check my privilege sometimes and that’s a really good thing. But then it crosses over into the fact that all we’re doing is typing on keyboards, How are you affecting the world around you on a level that’s direct?

The book has been advertised as a coming-of-age novel and…maybe because I’m 35, I thought it was more a book about motherhood.

I think there’s such a difference between what you put into a book and how the book has to be marketed. We’ve been very lucky to work with First Second, who got the nuance of the book. I wanted to make a book that communicates to different people at different levels.

It has been fascinating, because [teens] read it on a literal level—for them, what the characters say is true. So maybe that girl Jenny was cheating on her boyfriend because she said so, but maybe not! They ask questions that adults would want to ask but think are too silly. One of the girls asked me “Why didn’t the mom just tell the girl what was wrong?” That’s a really big question and that’s what the story is about. Ideally, at different parts of your life, you’re going to interpret the story differently. When we did Skim I was 24. You can tell we’re totally not interested in the parents. The parents do not have a lot of nuance in Skim, but we were much more fascinated with teenagers.

By giving so many characters the opportunity to address one big world you’re covering a lot of anxieties. It’s great.

I think that Mariko and I have always been interested in the juxtaposition of contradictory things. I’m always trying to remind myself to give the readers credit and to be okay if people don’t get something. Which is really, really hard. And I see my students struggle with this all the time—you want everybody to love you and you want everybody to love the things you do. It’s totally natural, but my parents don’t get the book, for example. My mom doesn’t get it at all and it’s fine because this book isn’t for her. I don’t feel bad if somebody doesn’t like it or doesn’t get it. Hopefully your point of view is strong enough that it really resonates with the people who do get it. That’s the thing I try to impress upon my students.

You don’t have to make everybody like what you do. And the things that you’re interested in? Chances are somebody else is interested, too. Trying to communicate those things just through existing is really powerful. All of my students—a lot of them are young girls—are interested in comics. It’s awesome.