What the parallels between the violent murders of The Walking Dead’s Glenn Rhee and Vincent Chin tell us about being Asian in America.

July 20, 2017

When I started watching The Walking Dead, I thought the show needed flashbacks. Based on Robert Kirkman’s comic of the same name, The Walking Dead follows a group of survivors banded together in post-apocalyptic Atlanta, where the dead walk around—“walkers” they’re called, never zombies. It is a world with no pre-existing zombie lore. No George A. Romero, no Zora Neale Hurston, and no flashbacks.

“You know, flashbacks like they do in Lost,” I told my husband, Quincy, as he set down our Sunday dinner.

He’s the one who got me into the show. A comic book and sci-fi fan, Quincy is a self-professed “Black nerd.” We had begun to watch The Walking Dead together each Sunday evening over plates of his signature salmon and sweet potato fries, the menu unchanging, our own ritual of nerdom and nourishment.

“You know how in Lost they cut back to periods of their lives before the plane crash, those origin stories?”

“Different show, baby,” he said, cutting another piece of salmon.

I quietly fumed at his logic. There are rules that govern any science fiction or fantasy universe, amid any and all kinds of chaos and wildness. Unlike in Lost, in The Walking Dead there is no time for the past. Or, more simply put, there is no time-past. History, like water, medicine, food, and life itself, is a scavenged thing. Take what’s necessary, what’s useful to the present. The rest is a luxury.

Even the word “past” is a luxury; most often on the show it is referred to as “before.” Characters ask one another: “What did you do before all this?” or, “before it all changed?” One survivor, Sasha, is even more efficient. She recounts a portentous dream, simply saying: “We were at the beach, but it was before.” Sometimes the word holds on its own like that, no more time stamp needed.

Can I even like a show like this? I wondered then. What are we but the past we carry? What constitutes our stories? Our survival?

And then came Glenn.

I wake up in the middle of the night not so much with a start but with a gnaw, like when you become aware of your own hunger, as if something has been eating at you for longer than you had realized.

Seven years and many servings of salmon and sweet potatoes later, I not only had fallen in love with this flashback-less show, but was now also grief-stricken over the brutal killing of nearly every fan’s most beloved character: Glenn Rhee.

The Korean American Glenn was the only character of Asian descent within the core group of survivors we follow in the nearly seven-year long run of The Walking Dead. Anger swelled among the show’s fans after Glenn’s death became one in a long line of characters of color to get the axe. There was anger because the death scene was incredibly gory: Glenn was bludgeoned to death with a baseball bat by yet another big bad white man villain, Negan.

The season 7 opener, titled “The Day Will Come When You Won’t Be,” earned the nickname “The Day Will Come When You Won’t Be (Watching).” On social media, fans professed they were turning away from the show. The Verge’s popular weekly recap column “The Walking Dead’s Quitters Club,” which was premised on the fact that one day the “Quitters Club would actually quit,” effectively ended its run that week, and show numbers did in fact drop.

“The Day Will Come When You Won’t Be” was directed by The Walking Dead’s longtime makeup special effects supervisor, Greg Nicotero, whose first major special effects makeup job was on George A. Romero’s 1985 zombie classic, Day of the Dead. Under his supervision, gore is a cast member unto itself, and “The Day Will Come When You Won’t Be” is an exemplar of Nicotero’s style. The episode debuts Negan, the brutal leader of a community called “the Saviors.” In the previous season the Saviors often made appearances without Negan. “I am Negan,” members of the Saviors often said during confrontations with our survivor group, assuming this white man’s name regardless of their gender or race. Loyalty trumped personhood.

In this episode, Negan has got most of our survivor group down on their knees not merely to meet their death but to meet “Lucille.” Echoing the name of B.B. King’s beloved guitar, Lucille is Negan’s barbed-wired-festooned baseball bat, his go-to weapon and, sometimes, instrument of mercy—a blow to the head from Lucille prevents zombie resurrection. Negan begins to wave Lucille in his hand and sing. “Eeny, meeny, miny, moe…” he hums as he points the bat towards the members of the group. At the end of the rhyme, he lands on the lovably smarmy Abraham and swiftly bludgeons him to death. We think he’s finished. But then the group’s long-time bad boy-heartthrob Darryl lunges at Negan. Negan in return goes after one more. Not Darryl, but Glenn.

The best one can say about this scene is that Negan goes for the head. We do not see Glenn return as a zombie. But the killing is long and protracted. What I remember most is seeing Glenn’s eye pop out of the socket, hearing him tell his wife, the pregnant Maggie, how much he loves her, talking from some place beyond sight and sense.

“I’m not sure I feel like eating,” I remember telling my husband, looking down at the sweet potato and salmon he had so lovingly made. I’m the jock of the house, and I joke that I’m always hungry and love saving it all up for our Sunday ritual. It wasn’t that my hunger was gone. I’d just had enough.

That night we managed to finish our food, but we did break another tradition. We did not watch Talking Dead, the Chris Hardwick-hosted wrap-up show that follows The Walking Dead. I had often looked to the after-show to situate the past. It was where the actors and show’s crew could reflect on that night’s victories and losses and when callers and audience members could ask questions. Chris Hardwick once joked that the show served as a form of “therapy” complete with a couch.

“No way,” Quincy said. “There is no making sense of this.”

Waking up in the middle of the night, I turned and watched Quincy, sound asleep. I appreciated that he took Glenn’s death to heart as much as I did. I loved his refusal to watch Talking Dead, which to me felt less like mere refusal and more like an act of resistance.

I couldn’t get back to sleep. Something drew me up out of the dark and made me open my eyes—a gnawing at the corners of my mind that, with the quickness of a flashback, turned into an image:

First the baseball bat, then the dead man rising again. Not Glenn, but this time, Vincent Chin.

The bat that Vincent Chin’s murderer, Ronald Ebens, used 35 years earlier also had a name—it was a Jackie Robinson model Louisville Slugger. This was Detroit, 1982—30 years after Robinson had changed the game, 20 since he had been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame for doing so. And Asians were in the eye of a violent racial storm. American automobile plants were shutting down, and the rise of the Japanese-made car was being blamed for cutbacks at auto plants. In Detroit, people routinely demolished Japanese cars with baseball bats in a show of frustration and force. The United Automobile Workers union even took part; UAW locals marched into town one Labor Day and battered Japanese cars with sledgehammers.

At first it seemed like another barroom scuffle. The barroom was Fancy Pants, a strip club. Ronald Ebens, a local auto plant foreman, and his stepson Michael Nitz were sitting directly across the dance runway from Vincent Chin and his friends. Ebens had his eye not on the runway but on Vincent.

I imagine Ebens watching him—Vincent surrounded by his buds laughing, ordering another round, the vodka they preferred, tipping the dancers every chance they got, Vincent using the tip money he had just earned from his shift at the Golden Star restaurant.

“It’s because of you little motherfuckers we are out of work,” Ebens hurled across the runway. And then the words: “nip” and “chink.”

Ebens says Vincent dealt the first blow. Interviewed in the 1987 documentary Who Killed Vincent Chin, Ebens laments: “He come around and sucker punched me, and that was the start of it all right there, I never even got a chance to stand up, never seen it coming, that’s the way the whole thing started.” This affront warranted Ebens hunting Vincent down long after Vincent left the club. Nitz held Vincent’s arms back as Ebens struck Vincent again and again until, as one cop put it, “there was brains layin’ on the street.” Ebens swung the Jackie Robinson bat with such force that it broke the handle.

Vincent’s mother, Lily, caught him on his way out their house. He was heading to Fancy Pants. She didn’t like him going to strip clubs.

“Ma, just one last time,” he said.

Maybe Vincent meant it. Maybe “last time” just fit the occasion for the outing, his bachelor party, a party with no one more than Vincent and three friends.

Bob heard “chink,” and Jimmy heard “nip.”

Gary’s the one who heard Vincent reply, “Don’t call me a fucker, I’m not a fucker.”

And later, long after the club, it was just Jimmy in earshot. Jimmy, who followed the route Vincent took after he caught a glimpse of the bat in the Fancy Pants parking lot. Jimmy, who suggested the fluorescent protection of the Golden Arches when he caught up. Jimmy, to whom Vincent yelled out “scram” when he saw Ebens coming with the bat in hand. Jimmy, the only other Asian person in the group. Jimmy, to whom Ebens turned and said after the cops came: “I did it, and if they hadn’t stopped me, I’d get you next.”

Jimmy heard Vincent’s last words emanating out of his disembodied head: “It’s not fair.”

“T-Dogging” it is called—when a Black character on The Walking Dead is killed. The phrase was coined by The Root’s Jason Johnson and it takes its name from the original lone Black survivor of the group, Season 1’s Theodore Douglas, nicknamed “T-Dog,” who was killed just as his character gained depth. Most often the “depth” is earned through sacrifice–assuming the position, albeit momentarily, as the group’s moral compass and then risking death for the greater good of the group. In his final scene, T-Dog heroically charges towards a herd of walkers so that his companion, Carol, can escape.

Glenn stands out for the lack of blood on his hands. Over the course of his seven seasons he takes only two human lives, and the second life Glenn takes is on behalf of Heath, a young Black male very much like Glenn himself, so that Heath can keep his proverbial hands blood-free.

Glenn outlasts nearly all the Black characters on the show. Michonne is a close second: she is a Black woman who joined the group full-time in the third season and remains in the fold. She is most identified by her katana, a weapon with which she slices through zombies and human enemies alike.

Glenn, by contrast, is most identified with the pocket watch bestowed upon him by group elder Hershel. If you look closely, there is a small compass set right within it.

Unlike the T-Dogged, Glen survives and thrives. But his belonging seems to require unparalleled goodness, requires a steady grip of not a weapon but the group’s moral compass.

The SHOT HOLDS, and just when we think there’s nothing left to break the silence.

A SOFT CRACKLE OF STATIC. A voice.

Voice

(filtered) Hey, you. Dumbass. You in the tank. You cozy in there?

END CREDIT MUSIC begins, as:

CAMERA CLOSES IN as RICK turns his head, stunned. Staring toward the forward compartment at the radio…

These are Glenn’s first words, at the tail end of the pilot, introduced as a disembodied voice emanating throughout the army tank radio that our hero, Rick Grimes, is stuck in.

Rick was late to the apocalypse; he woke up from a coma after being shot before the epidemic had begun. We calibrate to the new world order (or lack thereof) with him.

By the end of the pilot, Rick is failing pretty hard. He has taken refuge from walker-swarmed streets in an army tank that, as the shooting script describes, “will very likely be his tomb.”

Unless you have read the comics, there is no way to know whose voice bursts into Rick’s catacomb-tank. We just know the voice is resourceful, radioing in, direct (“Hey you, you in the tank, you cozy?”), and, indicative of a most underrated aspect of survival, unabashedly smart-mouthed (dumbass, cozy).

To Rick’s “we’re not in Atlanta anymore, Toto” innocence, this voice sounds proficient in apocalypse.

And there is something about the casual banter of hey you, cozy dumbass, that is even a bit nostalgic, the ambling swagger that one would think is more befitting of before.

And in that way, Glenn’s voice sets the tone for the show. A present that is forever channeling the past. A soft crackle of static.

There is no time-past—that, above all else, seemed to be the verdict in the case against Roger Ebens. No time for a past with any trace of Vincent.

At the trial, not one representative from the prosecutor’s office or any advocacy group was in the courtroom. Only the defendants, Eben’s and Nitz’s legal team, were able to present their case before the court.

There was no jail time, not even the 30 days you’d get in Detroit for killing a dog. Just probation, a $3000 fine, and court costs.

There was no mistaking what really guided the verdict, dealt by a judge who ignored the psychological evaluation that concluded Ebens deserved not only prison time but treatment for alcoholism, a judge who had been captured in a Japanese WWII POW camp, a judge who said the murderers “weren’t the kind of people you send to jail,” adding, “You don’t make the punishment fit the crime: you make the punishment fit the criminal.”

There were no witnesses or family called to testify—not even Lily Chin, who responded to the judge by way of a local paper: “These men wanted my son to die. They did not hit him in the body. They hit him in the head.”

Sometimes, though, time moves in two directions. A verdict becomes a flashpoint, last words turn into first words.

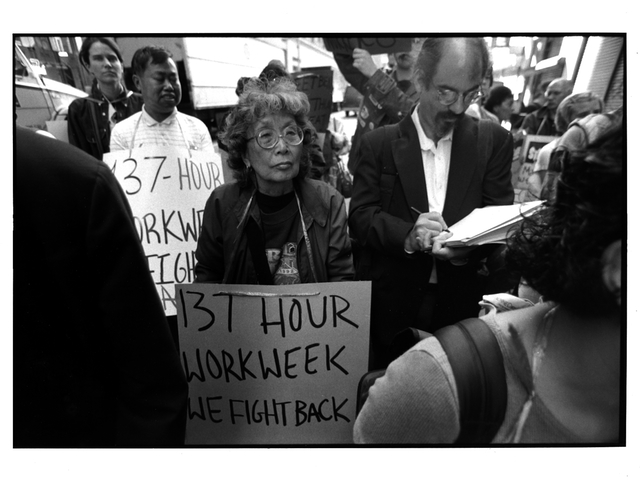

“It’s not fair,” the protest placards read at the march organized in Detroit in the wake of the verdict. Vincent’s last words were taken up as a rallying cry by Asians across class and cultures: by waiters, restaurant workers, chefs, laundry workers, housewives, engineers, and scientists; by business-owners who shut down their stores so they or their workers could participate; by Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, and Filipinos; by scurrying children and wheelchair-bound seniors alike.

The phrase was honored with precision: the signs all uniform, the words all in straight lines, chants and movements choreographed in 20-second intervals. The joke went: because the planning committee had so many engineers, GM scientists among others, this had to be the most “precisely planned demonstration in history.”

But if you looked closely, there was only one primary calculation to determine all that followed.

His words stood in English, with no other language in sight.

English-only, they said, making their intended audience clear, white America.

His words not a luxury, a scavenged necessity.

“It’s not fair.”

When the verdict of the Chin case came out, it was almost exclusively picked up by local news outlets and smaller Asian American community publications. The Los Angeles Times, though LA had a sizeable Asian population, held only a two-paragraph wire service story on the judge’s decision. The New York Times had nothing.

Things picked up steam in the most unlikely of places for the beginnings of a movement—a car rental shop. Helen Zia, a long-time activist and co-founder of American Citizens for Justice, a new Asian American advocacy group that was working to challenge the judge’s decision, was waiting in line. She noticed that the tall Black woman in front of her had copies of the Detroit News and the Detroit Free Press open to articles about the Vincent Chin case. Then she spotted a small notebook embossed with the words, “New York Times.”

She made good use of her wait-time. “Are you interested in this case? I have some press packets right here, if you’d like.”

The reporter turned out to be Judith Cummings, the first Black woman to head a national news bureau for the New York Times. She was in Detroit visiting family and looking for a story to do while she was there.

Cummings’s piece included details that had not been mentioned in previous national coverage outside of ethnic new media. She made sure to mention how no law enforcement officials had come to the club to question employees or investigate the case. She included voices from the prosecution including Liza Cheuk May Chan, who said Judge Kaufman’s decision was based on ” ‘material errors of fact’ in the information he considered, including the question of how the fight began.”[1] And she made room for a discussion of race: an “ill feeling against Asians” in Detroit due to the losses of the auto industry.

The story led to national media attention that spurred reporters to delve into the case with more nuance and depth, particularly into the yellow peril inscribed in the auto industry: the United Auto Workers parking lots with “park your import in Tokyo” stickers and the union’s sledge-hammering of imports on Labor Day, the “auto-war” compared to Pearl Harbor, the aggression embedded in “buy American.”[2]

By 1984, all this public pressure, and the joint work of Helen Zia and Liza Chan, led to a federal civil rights hearing—the first involving a civil rights violation of an Asian American to be heard by a federal court.

A red Dodge Charger is coasting down a highway that looks a bit like two kinds of afterlife. There’s the side that looks more like hell than heaven—the side clogged with a wreckage of cars, an evacuation that never came to be—and there’s the one free and clear of any signs of the epidemic.

Before we even see the Dodge coming on the clear side, we hear its car alarm. As the red speck grows, a back beat slips in, a Bo Diddly cover with a bass-line moving in time with the alarm blast, and then a yell, a cheer—it’s Glenn’s voice. This is how the second episode of The Walking Dead ends. Glenn, not the sheriff, rides into the sunset in the most American of transports and to the most American of songs and in the most American of outfits—a baseball cap and matching jersey.

His unabashed smile as the engines roars reveals that he is well aware of what this car can do on an open road.

The “supply runner” of the group, Glenn has always been skilled at finding the best way in and out of a crowd of walkers. It is the way he navigates Rick out of the tank. It is the way he continues to organize others to get out of the mess Rick started. It is something he does without apology, without deference, and with a little bit of annoyance—“I don’t get in this trouble when I go out on runs on my own,” he says. “You better just trust me,” he says with growing impatience. It is a clue for what life looked like for him before.

“Hey kid, what did you do before all this?” Darryl asks him in the fourth episode.

“Delivered pizzas, why?” he says.

I was surprised by this detail. And still craving flashbacks, I hung upon it. It pointed to a “before” free of the tiresome types of before that emerge around Asian characters. It is the detail that kept me watching, if only to follow this character a little bit further.

Maybe it was not really to learn more, await any kind of flashback. Maybe it was just that Glenn, beyond the familiar banter, had a type of knowing that seemed relatable, applicable not only to combatting an onslaught of a horde of zombies, but also to handling the everyday things that press against Asian American survival.

This is a type of knowing that seems embedded in Glenn’s first words on screen: “Not dead!”

Glenn’s got his hands up and Rick is pointing a gun to Glenn’s head. Rick, who has made a walker shooting gallery out of the escape route Glenn gave him.

“Whoa! Not dead!” are the exact words.

Whoa! Not dead! and I think not of Rick’s gun or whatever the hell is on the other side of the highway at the episode’s end, but all the other ways Glenn has had to stay not dead.

Of the five-year court battle that followed Vincent Chin’s murder, there is one detail that stuck with me: Lily Chin stuffing and pulling cotton out of her ears so that she did not have to hear the gory details again and again, her own kind of before and after in this eternal present.

“Every time she saw a camera, it reminded her of the tragedy and…she got very emotional,” said Rea Tajima-Pena, who, alongside Christine Choy, co-directed Who Killed Vincent Chin. “Off camera she was the funniest. She loved to cook. She was always trying to set us up.”

That humor I imagine is what Vincent inherited from her. He and Jimmy were laughing in the McDonald’s parking lot when Ebens pulled up.

“[Ebens] was humiliated because Vincent was laughing when he got to McDonald’s,” said a witness, a man Ebens paid to help him track Vincent down.

A killer’s “humiliation.”

It must have been words like these that are worth a piece of cotton. Not just the gore. Words that make me wonder, what was it like for Lily to hear all that quiet?

“Walker bait,” Maggie calls Glenn in the sixth episode of the second season, “Secrets.”

Earlier in that season, Maggie, new to our gang of survivors, watches a few of the survivors group usher Glenn down a well to kill a walker. The rope they’re using to lower Glenn down goes loose, and he almost hurtles to his death. They scramble to pull him out. “Back to the drawing board,” Dale says in resignation. Glenn, climbing out of the well, is panting but smiling. “Says you,” he rips, passing the rope that was once tied around him to Dale. Turns out he managed to lasso the walker.

Maggie isn’t as ecstatic as the others. “You’re smart, you’re brave, you are a leader. But you don’t know it. And your friends don’t want you to know it. They’d rather have you fetching peaches. There is a dead guy in the well, send Glenn down. You are walker bait.”

“Walker bait,” my husband and I would say sometimes to one another, mostly in moments where we thought we were being used by someone or another. Mostly in the context of white America.

Walker bait when the federal trial is stymied by accusations of “coaching” witnesses, while the prosecution has only asked the questions the police never cared to.

Walker bait when the retrial is held in a city where only 19 of the 200 potential jurors had ever seen an Asian American person; where evidence of Ebens’s racist statements was deemed inadmissible because the jury might be “repelled” and “resentful” of the person who said them; where the judge ruled the autopsy photographs “not relevant.”

Walker bait when the defense takes the position that Ebens’s extreme aggression was understandable in light of his job loss; when that phrase “bar brawl” as in “just a bar brawl gone wrong” is used again and again, until the killers walk away without a day in prison. When Ebens, decades later, millions behind on his fine, only takes issue with the price.[3]

I sometimes think about why we found Glenn’s death so surprising. It echoes a question I often ask myself–why do I find racism so surprising? And a question I have been afraid of asking–why did Vincent find Ebens and Nitz so surprising—enough at least to throw a punch?

Then, I think of my co-worker, a white man, who spied me doing my Walking Dead research at work. Peering into my cubicle, hovering over my body, he told me how much he hates Glenn. “Don’t you?” he said. He told me that he wished that the writers left Glenn and Michonne, the Black swordswoman in the survivor group, alone. The writers should not have let them find love and a sense of place. They were better before—when they were not so much two human beings but a gopher and a “killing machine.”

In that moment, I felt the weight of a rope around my middle, guiding me down a well. I felt my hands tense around an office chair wanting to scream out “don’t call me little motherfucker.”

I did neither. I laughed nervously. I changed subjects quickly. I knew on some level that I was fetching peaches in my majority-white office, as I did.

I thought of Vincent’s two white friends and Glenn’s majority-white survivor community, and all the newspaper reporters who didn’t call Vincent slurs but did call him “oriental” like a rug, a carpet, an object, a machine.

I thought of the PBS higher ups who didn’t “trust” Rea and Christine as they made “Who Killed Vincent Chin.” PBS funded the project but only under the condition that they work with a “Caucasian script consultant.”

I thought of all the white cameramen who kept quitting on them until Rea and Christine learned to operate the cameras themselves.

And I thought of Lily Chin, who knew better than to trust a white camera, prying white eyes, with her whole, funny and vulnerable self. Lily who knew that, even though we can be so many things at one time, a world under the bat-grip of white supremacy wouldn’t know what to do with all that.

And maybe the day will come when this mistrust will no longer be.

Until then, I ask you. You in the office. You in the strip club. You on the couch. You trapped in the armored tank that is white America. You cozy in there?

[1] Cummings, Judith. “Detroit Asian-Americans Protest Lenient Penalties for Murder.” New York Times 26 April 1983.

[2] Campbell, Bob et al. “Japan Bashing.” Detroit Free Press 27 October 1985: 17. Print.

[3] Wang, Frances Kai-Hwa and Guillermo, Emil. “Man Charged With Vincent Chin’s Death Seeks Lien Removed, Still Owes Millions.” NBC News 11 December 2015.