What kind of exhibit on revolutionaries would it be without a living Palestinian? The rub of course is there are so few of you.

September 16, 2021

I watch them stare at me from behind the glass that I was once told by The Director is bulletproof. I remember thinking that was sweet. I told her that I thought that was sweet. She looked confused, so I explained that not since my father was shot in the head as he swung me around our backyard in Hebron did someone care to protect me from bullets.

She laughed and patted my head and said, with the same tone she would sometimes conjure when claiming that I’d been misjudged, prejudged, or judged harshly, that the glass wasn’t there to protect me from them. It was there to protect them from me.

The American Museum of Natural & Social History numbers three buildings in the Upper West Side of Manhattan. It houses multiple exhibits—some permanent, others temporary—all of which cover the history of the universe and of people. Sometimes both at once.

□ □ □ □ □

I toured the museum upon my arrival, and was made to see the dinosaur bones, the model of the Taj Mahal made of recycled materials gathered at the Taj Mahal, the ecosystem of a cross section of a region in the Amazon, United States greasers, a scale model of a blue whale, and Mansa Musa’s court. Some of the exhibits contained live human models that sat, stood, or mock-ran in place. I saw a panicked Einstein leaning on his desk in Berlin; the race for General Relativity was on, and he was afraid someone else would solve his problem for him.

I feel the kufiya slipping along the back of my head. I see The Director standing in the back and to the left, next to Daveed, himself playing a young Fred Hampton, which is to say Fred Hampton. The Director looks upset. I can tell by her arms. Whenever they’re crossed I know she’s upset.

I remember the first time I met The Director. A bus picked us up from the prison on Randall’s Island, where we were held, and took us to the museum. Seated behind me was an elderly, balding man from Kazakhstan with a trimmed mustache and bright-red beard, and in front of me was a teenager from New Jersey with heterochromia and hair arranged in neat rows of spikes jutting out of her head, making her look like a pin cushion. Erasyl, the man from Kazakhstan, would become our driver, ferrying us daily from our residence, a former dormitory in the Village, to the museum. The latter named herself Darius. Later that day we discovered that we were to share a cell containing two cots, a mirror, and a sink in that former dormitory, which was formerly a gilded hotel.

The Director greeted us at the museum’s southern entrance, across the street from the mansions lining the road between Columbus Avenue and Central Park West. She introduced herself as The Director of Recent History and forwent a name. She had cold eyes, white hair, and an unnerving disposition. As we began our tour, I noticed she walked with a sense of urgency; museumgoers turned to watch her march, her arms swinging back and forth with intention. She led us through the ground floor while declaiming a truncated history of the museum, its mission, its founding principles, and Prison Models, the rehabilitation program initiated by some well-intentioned philanthropist that provided the museum use of prison labor, and of which the three of us were a part.

We made a left, then a right, and then two more lefts. I saw the Buddha, a map of the Great Barrier Reef, Incas tying knots, and the constellations as they appeared some number of trillions of years ago. We walked down two sets of stairs and through an underground hallway lined on both sides with floor-to-ceiling drawers, each one labeled with the name of the species sample it contained.

We arrived at a door. The Director opened it and led us into a waiting room. She pointed to Erasyl and Darius with one hand, and to the chairs lining the perimeter of the room with the other. She then pointed at me and then at a brown door. My heart rate, which was steady for my entire trip from the prison to the museum, and through The Director’s whole monologue during our tour, became stochastic.

I walked into an office similar to ones I’d seen in less bedecked albeit no less public buildings—a single desk, a screen, and an artificial plant in the corner. There was, however, a noticeable difference between those other offices and The Director’s office: Walls, shelves, and chairs emblazoned with swastikas. Dinnerware, cutlery, and a panoply of handkerchiefs, medals, knives, guns, and uniforms etched or colored with symbols of the Third Reich. Paintings of Goebbels and Gӧring, Eva and Eichmann, Himmler and Heydrich.

I sat in front of the desk and read the nameplate: Fury. The Director took her seat and noticed me reading her nameplate. “I tried to sound it out in the German, and they still got it wrong,” she said.

I looked up. “Your name is Fury?”

She laughed a hiccupy, honking laugh. “No, that would be silly.” I didn’t understand what she meant, so I nodded. She said, “And your name is Leila.”

I was shocked. “You know my mother’s name?”

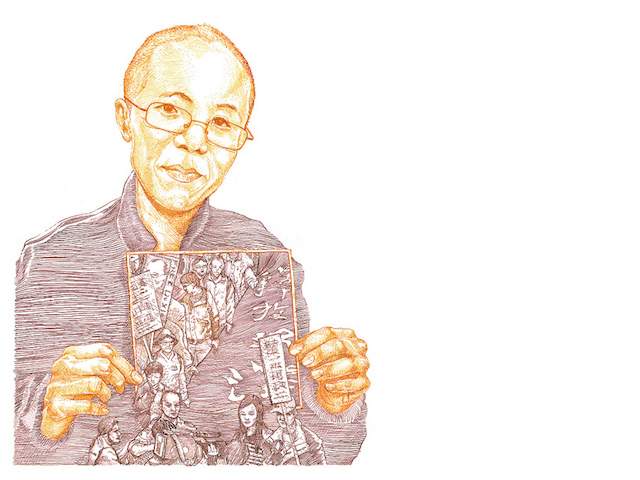

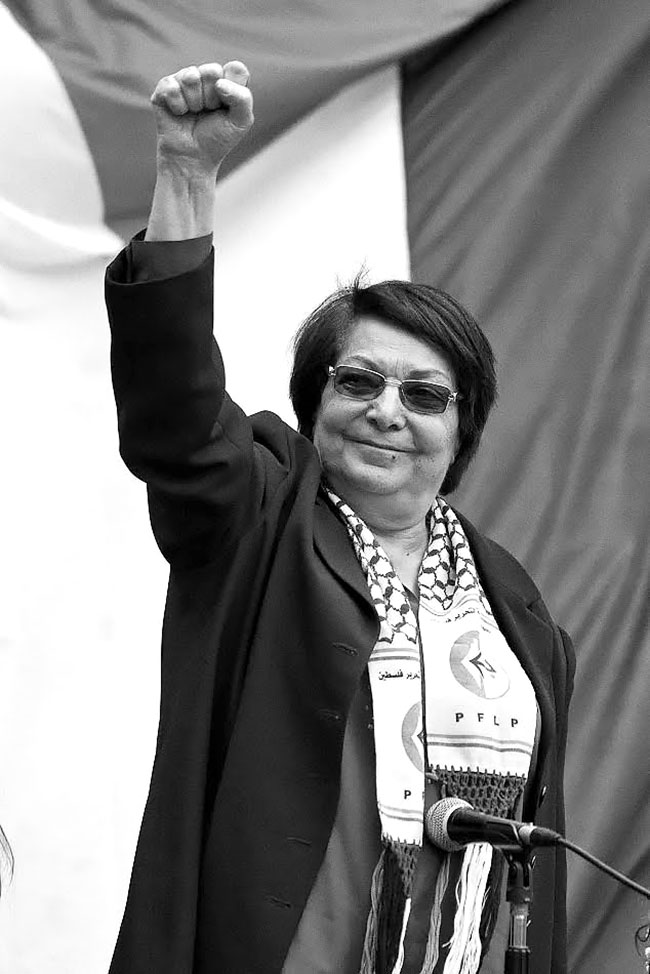

The Director smiled. “It’s someone else’s name, too. Someone very important.” She tapped her screen and turned it to show me the image of Leila Khaled. In the photo she looks away from the frame while holding a rifle in her lap, its barrel pointed at the ceiling, her kufiya halfway up her scalp. She’s 25 and looks self-contained. Strong. Determined.

“Some of the exhibits contained live human models that sat, stood, or mock-ran in place.”

“I’m Palestinian, too,” I said, maybe unnecessarily, considering The Director most certainly had a dossier on me. Perhaps she’d even read it. I thought of my father’s soon-to-be lifeless body maintaining its inertia, swinging me around as his finger tips loosened, eventually tossing me across our backyard.

The Director leaned back in her chair and grinned a disquieting grin. “I know,” she said. “You people sure like to protest don’t you?” She was referring to the reason for my arrest. I maintained equanimity.

“As I said during the tour, our patrons hold the highest possible standards,” she said. “That applies to everything: to the shininess of the floors and the shininess of the chandeliers and the accuracy of our still exhibits and the, um,” she turned the screen to herself and tapped something into it, “authenticity of our live human models. A large number of our patrons have been asking for an exhibit on revolutionaries for years. A larger number than you may expect. But in order to give them what they want, we needed a live Palestinian. What kind of exhibit on revolutionaries would it be without a living Palestinian? The rub of course is there are so few of you. And so when the Prison Models program told me that we had a living, breathing Palestinian at our disposal, I couldn’t believe it. I told them they must have the last one in America.”

The Director paused, I assume, for me to laugh. When she realized no guffaws were forthcoming she frowned. “I never understood the fascination with your people, considering how little you contribute to the world. But then again, interest in Palestine never has anything to do with Palestinians, does it?” The Director’s frown morphed into something like a snarl pretending to be a smile.

She tapped her computer, then turned it back to me. Again, it was Leila Khaled. “Your assignment, should you choose to accept it, is to be Leila Khaled. We have the best makeup artists in Manhattan, and they’ll make sure that you look just like her. We have the best interior decorators in New York, and they’ll produce a life-sized diorama that exactly matches the background in this photo.”

She sat back in her chair and interlaced her fingers on her desk. “You do this for me, and I’ll make sure you have a good life here. Instead of working on the farms in Long Island—-in the heat, without any breaks, all day long—you get to sit for a few hours a day in a temperature-controlled room, doing absolutely nothing. That’s it. Just sit there for the rest of your sentence. No back-breaking hard labor, no disrespectful prison wardens, no violent cellmates, no yard politics. All you have to do is pretend. And who knows, maybe, just maybe, if you behave and do a good enough job, I write a letter to the Prison Models program. And maybe, just maybe, they commute your sentence. Again, just maybe. I make no promises.”

□ □ □ □ □

The reason for my arrest is both predictable and boring. The sort of thing I always promised myself I wouldn’t get arrested for, if only to avoid cliché.

I had attended one of the semi-regular protests organized in the outer boroughs. It was, in fact, my first protest. I don’t remember what I felt, and I don’t even remember what pushed me to attend. All I remember is that within minutes of my arrival it turned violent. In the chaos a police officer mistook me for an instigator, tased me, and threw me into a van with fifteen to twenty others. We were sent to a jail in Queens, then bussed to the prison on Randall’s Island, during which time we were informed that each of us was sentenced to 25 years of labor on the wet farms. No trial—just the sentence. I heard hushed sobbing in the back. The person sitting in front of me began to weep. Someone wailed.

Before we were sent to the farms, Darius, Erasyl, and I were collected, told that we were part of a special program, and then sent to the museum.

I never liked protests. They’re so loud. And everyone is so emotional. Protests remind me of large spiritual congregations. My parents also distrusted both protests and protestors. “Look at these idiots,” my father would reliably say in our home in Hebron, whenever news of a protest broke.

My mother would add, “What if the government comes after them? What if the police track them down and hurt their families? Short-sighted idiots.” You can imagine how vindicated I felt when my life changed for the worse because of my attending a protest. I was right to avoid them all along.

When The Director offered me the role of Leila Khaled, I knew that I didn’t want to go back to Randall’s Island. And I most certainly didn’t want to spend 25 years working on the farms that sustain Manhattan, growing its food and cleaning its water. And so when given the opportunity to serve my sentence in relative calm, when offered the choice to perform a well-defined task and maybe gain my freedom slightly earlier than expected, I thought of three things: me, then me, then me.

□ □ □ □ □

One and a half years later, and behind the glass that The Director told me is bulletproof, the kufiya almost slips completely off my head. I catch it with my right hand while doing my best to maintain a facial expression that I hope conveys the anxiety that must plague a revolutionary, and the solidity of a 25-year-old woman enduring the gaze of a million, million eyes.

I look to The Director. It’s important that she not be upset. I watch as she uncrosses her arms and rubs her triceps, which is her way of telling me that she has goosebumps. A nonverbal way of saying, “Very authentic,” one of her favorite refrains.

“‘But in order to give them what they want, we needed a live Palestinian. What kind of exhibit on revolutionaries would it be without a living Palestinian?'”

I retrain my attention on the museum attendees. They come in almost every shape, though not necessarily in every size. Based solely on their clothing, they don’t seem to all be wealthy. Some wear designs I’ve never seen before and are adorned with colorful, luminescent jewelry. Others wear common shirts, pants, and shoes that look as though they’re made of seminatural cotton and artificial textiles.

I can hear the multiplicity of languages with which the attendees speak, muffled as their voices may be. On any given day I pick up notes of Spanish, Mandarin, Arabic, Hindi, and Kiswahili. Regardless of their particularities, every single museumgoer who stops to consider me has the same gawking expression, their eyes wide and their mouths a quarter open, their heads bobbing up and down like a rubber toy in a pool, angling to get a better look at the Palestinian.

A boy who can’t be older than eight leans on the glass with his hands. He asks his mother something unintelligible. She laughs, picks him up, and responds in English with a sonorous voice, “No darling she’s not a robot. She’s the real deal! Who is she? See it says right here.” She turns to the museum label adjacent to the glass and reads aloud, “‘Leila Khaled is a revolutionary who engaged in the struggle for Palestinian independence during the middle of the twentieth century. In 1969, she became the youngest woman ever to hijack an airplane.’ Isn’t that interesting, sweetheart? Oh look at that makeup!” Without looking I know she’s referring to Darius, posed adjacent to me as Marsha P. Johnson in front of a plaster model of The Stonewall.

While I’m fortunate enough to sit, Darius has to stand in high heels with both arms raised high above her head all day long. After our first day, she needed to be carried to the school bus that shuttles us to the residence, and then she needed to be carried to her cot, her arms barely moving. She suffered from leg spasms, nausea, and excruciating pain all along her back. While in bed, she shared the events that led to her arrest: One day, in the middle of a shift at a restaurant in the Bronx, a customer groped her as she bent over to pick up a cup that had fallen on the floor. In response, she smashed a pitcher of flavored water over said customer’s head. The police were called, and the rest was, as The Director is fond of saying, recent history.

Darius passed out with her arms raised, hands bent along the wall behind her bed so that she looked like she was dreaming of the backstroke. I covered her with a thin polyester sheet.

I stood and walked to the mirror and stared at my reflection. The best makeup artists in Manhattan dyed my hair and then covered my body with a tanning powder so that the melanin content of my skin matched Leila Khaled’s exactly. I was born with dark brown eyes, so they left those alone.

My reflection stared back at me.

The Director told me that as time went on, the powder would adhere to my skin and the dye would require fewer applications. Soon enough I wouldn’t have to do much at all to be Leila Khaled.

I sat on my cot and looked at Darius. A part of me wanted to know more about her and about her life prior to the museum. Did she have a family? Where did she grow up? What’re her dreams? Hopes? Has she ever been in love? I would never actually ask Darius any of these questions. Because in doing so I would run the risk of making a friend. And ultimately, there are no friends in prison.

□ □ □ □ □

I check to see if The Director is still watching. She’s not.

We file out of the museum one by one. As we exit, we’re handed boxed dinners to eat on the bus. Everyone is exhausted. I see Darius and a few of the other models congregate and give one another hugs. They turn to me and relax their foreheads, narrow their eyes, and purse their lips.

Last month, some of the models staged a hunger strike: For multiple days they refused to eat anything, tossing their food out onto the street before boarding the school bus back to the residence. Darius invited me to join the strike the day before it began. When I rejected her offer, she stiffened. “Do you think it’s ok that I’m in here for defending myself? Or that Daveed is here because he made fun of a cop? Or that you’re in here because you attended a protest?”

I crossed my arms. “I was just there to watch. It was my first time. I didn’t do anything.”

Darius narrowed her eyes. “And do you think it’s ok that you were arrested just for watching a protest?”

“Obviously I don’t think it’s ok,” I said, shaking my head. “But what am I going to do about it? What’s anyone going to do about it? Why try to fight a losing battle?” I wasn’t going to jeopardize any chance at reducing my sentence, even if that meant upsetting my cellmate.

On our way back to the residence during the first day of the strike, I quietly ate my food while seated next to Erasyl. “Spoiled children,” he declared. “Do you know what would happen to you in my country if you tried that? They’d kill you. Just shoot you in the head without asking a question. Those brats should be thankful. You’re doing the right thing, darling. You’re smart. Keep quiet. Eat your food. Survive, daughter. Survive.”

As we lined up outside of the museum on the morning of the strike’s seventh day, a collection of police officers materialized from the early morning fog enveloping Central Park. They moved quickly and efficiently, collecting any model who was on strike and tossing them into an unmarked and unsettling black van.

“‘How can you trust anyone in prison?’ Erasyl hums, ‘One day at a time. One day at a time.’ I shake my head, ‘Didn’t you call them idiots?’ Erasyl nods, ‘Yes. I am saying that you need to learn to live with idiots.'”

The strikers were gone for a week. Upon their return, they seemed even more exhausted than they did prior to their disappearance. They also resumed consuming food. I tried speaking with Darius during her first night back, but she ignored me. When I tried again, she turned her back to me. Since then, she and I replaced any actual dialoguing with curt exchanges, nods, and grunts. The rest of the models who went on strike have also ignored me. The models who didn’t join the strike were predisposed to maintaining their distance to begin with, just like me. I felt alone. Unmoored. Only ever thinking of me, then me, then me.

We board the old yellow school bus. As Darius and her friends move to the back, I sit in the front with Erasyl. The old man grins at me. “How are you today, darling?” he asks.

“I’m ok, uncle,” I say, smiling back. “Tired, but ok. How are you?”

Erasyl quips, “I have breath in my lungs and blood in my veins, so I’m doing well, thank god.”

I nod as we pass through empty streets flanked on both sides by pristine sidewalks that lead into buildings with awesome exteriors. Erasyl nudges me with his elbow as we merge into the West Side Highway. “You seem sad, daughter.” He nods at the back of the bus. “It’s those models isn’t it? And Darius?”

I shrug and shake my head.

“No, no, don’t lie to uncle Erasyl,” he warns with his left pointer.

I look up. Over the past year and a half, he has shared with me his affinity for god, love of volleyball (“a true man’s sport”), and stories from his childhood spent orphaned and disrespected by his extended family in Nur-Sultan. He’s told me about becoming a refugee in Lesbos, and his journey across every hurdle conceivable, including brutal seas, barbed wire, and bureaucrats. He ultimately gained entry into the United States through New York using forged documents, which were the reason for his arrest and imprisonment a few years later. I told him about my childhood, my father’s murder, and my arrest at a protest.

I sigh again. “I just feel like,” a pause enters the space between my words, “a traitor.”

Erasyl laughs heartily. “A traitor? You? No, darling, no. You’re not a traitor. Traitors get friends killed and spy on their countries for other countries and sacrifice their families. You’re no traitor.”

I feel my shoulders drop. “Then why do I feel so bad?” I ask.

I look up and notice Erasyl bouncing his head side to side without taking his eyes off the road. “I don’t know, but I found that the best thing to do in times like this is to face your fears head on,” he says. “Have you tried speaking to Darius?”

“I tried, right after she returned from wherever she and the rest of models were taken, but she ignored me,” I say. “So I ignored her. I thought I was doing the right thing. By ignoring her, I mean.”

Erasyl twists his beard with his right pointer. “I think you two need to speak. You’re going to be living together for many years. You need to rely on each other.”

I drop my head. “How can you trust anyone in prison?”

Erasyl hums, “One day at a time. One day at a time.”

“Didn’t you call them idiots?” I ask, shaking my head.

Erasyl nods. “Yes. I am saying that you need to learn to live with idiots.”

Back in our cell, and with our backs to one another, Darius and I quietly prepare for bed. I feel a hand on my shoulder, and I turn to find her standing over me. “Do you want to be free?” she asks.

I scrunch my face; one and a half years later the tanning powder still feels like a secondary skin forever adhering to my primary skin. “Of course I want to be free. We’re prisoners. Who doesn’t want to be free?”

Darius shakes her head. “We’re not in prison. We’re Prison Models.”

I reply, “And what’s the difference?”

She places her right hand over her left hand, and she moves her right hand along her left arm. “We ride the bus daily, with minimal supervision.”

“And?” I say, turning my hands over so my palms face up.

Darius sits on my cot. “Tomorrow we’re going to make a run for it on the way back from the museum. I can’t tell you how or what we’re going to do before we do it, but if you want, you can come with us.”

I open my mouth, and my jaw hangs slack for a moment. “How?”

She shakes her head again. “Can you just do me a favor?”

I nod hesitantly.

She holds my left hand with both of hers. “Distract the driver for us, will you?”

I shake her hands away. “What’re you going to do to Erasyl?”

Darius puts her hands up. “Nothing. He just needs to be distracted. I promise.”

My mistrust is legible, because Darius smiles. “Don’t you want to be free?”

That night I dreamt for the first time since becoming Leila Khaled. I dreamt of my home and my mother and my father.

□ □ □ □ □

I was born at the turn of the century in the slumbering upstate town of Hebron, which can be reached from Manhattan by car after a two-hour drive north-by-northwest. My parents were farmers who loved to read. They were fortunate enough to receive a primary, secondary, and post-secondary education largely subsidized by the state of New York, before public education became unaffordable. They taught me sentential and modal logic, ancient and modern philosophies, biology, chemistry, and physics. When I was old enough, they introduced me to history, a subject that had the power to paralyze my father. My mother described the catatonia he slipped into whenever he tried to answer a historical question in full as like being unmoored from reality, lost in a past that only exists in minds fleetingly and in books sparingly. They taught me about Palestine.

My parents also prioritized self-preservation. After every lesson on the revolution, they would warn me about fighting the system. Politics and power and money are for the already political, powerful, and moneyed; we are just fleas, competing with other fleas for crumbs. All we can do—all we ought to do—is survive. At every turn and given any chance, they would remind me that, while friends are nice and family is helpful, I must only ever think of me, then me, then me.

My mother was arrested following my father’s murder. After she was taken away, a couple of police officers drove me to my aunt’s home in Queens. The leather seats in the back of the police car were warm. Though my aunt insisted that my father was assassinated by Mossad, the police officers who drove me to her home joked that my dad must’ve done something terrible to get his wife to kill him like she did. They couldn’t believe the amount of blood that covered my face.

I see the hole in my father’s head, and I sense the center of gravity shifting from between our arms through to my stomach as I fly through the air.

“My mother described the catatonia he slipped into whenever he tried to answer a historical question in full as like being unmoored from reality, lost in a past that only exists in minds fleetingly and in books sparingly.”

On my eighteenth birthday, and in part due to my first transcendent experience with alcohol, I asked my aunt what made my father so special, so dangerous, so stressful that Mossad agents would bother driving two hours north-by-northwest from Manhattan to kill him. She turned to face me, grabbed my shoulders and said, “Sweetheart, you’re drunk. Go sit and I’ll bring you a glass of water.”

A few months later I was arrested for attending a protest.

□ □ □ □ □

On the day of the planned escape, I wake up feeling disoriented. Darius and I change quietly, line up with the rest of the prisoners, and board the bus. I assume my usual seat next to Erasyl. He nudges me with his elbow. “How did it go, daughter? Did you and Darius speak?”

I look up at him. “We did. She told me what you told me: I’m no traitor, and I shouldn’t feel bad.”

Erasyl smiles a wide smile and claps his hands as the bus barrels northward along the highway to the museum. “Ah ha, fantastic. I’m so happy for you, daughter. So, so happy.”

For the rest of the ride I consider Union City’s crumbling skyline across the river as Erasyl recollects the story of his treacherous journey across the Mediterranean from Turkey to Greece.

In the museum I see The Director pass and I seize up. She doesn’t stop to check on me, and continues on her way across the exhibit, swinging her arms back and forth. I relax.

Erasyl was right: Why not make peace with the person I’ll be sharing a cell with for the next however many years, especially if I’m asked to do so little? After all, the thought of gaining my freedom, suddenly and without doing anything, seems so ludicrous that I don’t really think anything of consequence will happen. The rebellious models will be caught, and then they’ll probably be taken away for another week, maybe two. But nothing more.

We line up outside of the museum. Darius stands behind me and whispers, “No matter what you hear in the back, just keep Erasyl distracted. I promise he’ll be OK.” I don’t respond.

We board the bus, and I assume my usual position. We pull out onto the street. Erasyl whispers, “There’s something under your seat.” I reach down and pull out a worn cardboard box. I open it to find a stale glazed doughnut.

I look up at Erasyl, who grins and whispers, “It’s my birthday today, and I thought you and I could celebrate. One of the security guards at the museum was kind enough to sneak us some treats.”

He reaches under his seat with his left hand while holding the steering wheel with his right, and he pulls out a similarly worn cardboard box. He opens it to reveal a jelly doughnut.

“When I first immigrated to this country, I managed to find work at a doughnut shop. You know, darling, immigration is very difficult. You have to learn the language. You have to learn the places. What people like to do, what they don’t like to do. What to say and what not to say. Sometimes, the wrong thing said accidentally can get you killed. Immigration is very, very difficult. So many people I knew who managed to get into this country couldn’t find a job. They wound up on the street. They said they looked for work and no one would hire them. But between you and me, daughter, I never believed them. They always seemed so lazy to me. So, so lazy.”

We enter the highway, and the bus picks up speed. I look at Manhattan’s skyscrapers. Some shine in the darkness like beacons. Others are part of the darkness, their silhouettes accentuated by the radiant buildings next to them.

Erasyl continues, “I found that job at the doughnut shop and I felt so lucky. Day and night I would make these things. A lot of the time I only had them to eat. I got so sick of them. My daughter, god rest her soul, loved glazed doughnuts. I would bring them to her every night on my way home from work, you see? Her mother died giving birth to her, and she was my everything. I loved her so much. So, so much.”

His voice cracks slightly. I look at him and I see the tears reaching the edges of his eyelids. This is the first time I have heard this story. Erasyl tucks his beard into his chest and takes a deep breath. “God is good my daughter. God is good. Eat eat. Who knows when we’ll have another chance to enjoy something sweet.”

I feel my heart beat and my tear ducts burn. I sense the edges of my lips twitch. I look at him again and consider the tributaries lining his face. I put my hand on his shoulder. He smiles, “Thank you, daughter.”

I hear a banging against a window. I see Erasyl’s eyes drift to the rearview mirror. Without thinking I ask, “Uncle, what happened to your daughter?” Erasyl’s eyes turn to me. Suddenly, a window shatters, and then another.

Erasyl tries to turn his head to look, but I grab his face. “Uncle, please, what happened to your daughter?”

□ □ □ □ □

He shakes his head free. “Daughter, what is wrong with you?”

As more windows break, Erasyl turns and pulls the bus over to the side of the road. He stands and turns to look. “What is going on?” he says.

Before he can finish his sentence, Darius leaps over the seat behind the driver’s seat and slashes his throat. Erasyl struggles to catch his breath as blood flows down his shirt. He grabs his neck. I look at Darius, who stares back at me, her face speckled with Erasyl’s blood. I turn back to Erasyl as he opens the bus door and stumbles onto the street. He falls face forward, with his hands around his neck; a pool of blood forms around his face.

Darius and a collection of models rush out of the bus. I run after them and yell, “You said you wouldn’t hurt him.”

Darius stops, and without turning says, “You’re free.”

Along with the other models who ran out of the bus, Darius jumps into the Hudson River, which looks like an undulating pool of metallic liquid. They all swim toward Union City furiously. I look back at the bus, and I notice a handful of other models seated in place, eyes trained forward, unmoved and unmoving. I look back to try and spot the models who jumped into the river, but they’re no longer visible.

Editor’s Note: This story is part of a series of writing about Palestine and Palestinians, written by Palestinian American writers, published in the wake of the Israeli government ordering the expulsion of Palestinian families in Sheikh Jarrah, which led to Israeli raids on Al-Aqsa Mosque compound and aerial bombardment of Gaza in May 2021.

You may also be interested in these related stories:

After Javon Johnson: When the Cancer Comes: Grappling with the burden of keeping a legacy alive

Coming Out of the Palestinian Closet: And finally smashing the eggshells after 35 years on my tiptoes

The Nakba is Present: The looming threat of yet another mass expulsion of Palestinians is ever present

Rites of Return: What does it mean for a Palestinian living in the United States to resist?

1948: An 11-year-old boy was forced to grow up fast when occupying Israeli soldiers seized his tiny Palestinian village