An 11-year-old boy was forced to grow up fast when occupying Israeli soldiers seized his tiny Palestinian village.

August 29, 2017

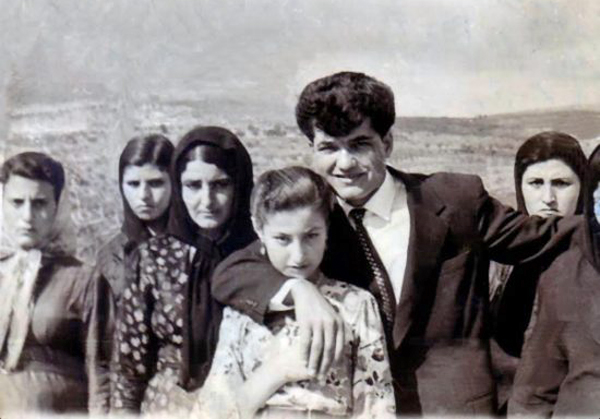

The pale sky quickly grew bluer as Hatim made his way up the mountain. He raced against the morning, the heat already intensifying as he climbed towards the rising sun. It was dawn, in the summer of 1948. Hatim was 11 years old, his shins freshly scraped from the thorny bushes that pepper the hillside. His steps were light and fast. He carried a ceramic jar of water, the condensation causing his already sweaty grip to tighten. The mountain stretched before him; he knew that somewhere out there, his brothers were hiding, nestled in its face. Hatim’s precious cargo sloshed as he stumbled over a rock, eyes straining for a dark mouth – a cave where his brothers might be hidden.

They saw the trucks at a distance before they heard them. It was one day earlier, the village warm and busy. The trucks rattled down the dusty, quiet road from the west, the only path in and out of the village. It was nearing noon, the sun high and hot in the sky. There were five or six trucks, plain but noticeable, obtrusive against the otherwise still hills. Word quickly spread through Arrabeh. The army was coming.

The air had been tense for a long time. The villagers knew that their turn was coming. In Arrabeh, everyone had heard what the soldiers’ arrival meant, what happened when their trucks rolled into the town square. Refugees from nearby villages had passed through Arrabeh, sleeping under the olive trees where Hatim played and bringing stories of death. Ten miles to the east, in Eilaboun—the village where, decades later, Hatim’s daughter would attend high school—the army would soon arrive.

In Eilaboun, soldiers had selected sixteen young men, line them up with the entire village watching, and shot them dead. This was a precedent. The story traveled like wild fire, along with the shocked, grieving villagers. It was repeated in village after Palestinian village. Similar stories and worse from Tantura and Deir Yasin had already echoed through Arrabeh. Helpless dread filled the village as those trucks rumbled closer.

“They were afraid, of course, but could not help being curious, only feeling the full gravity of the day in flashes, unable to reconcile their childhoods with the guns in the square.”

The roofs of the village were dotted with white flags of surrender. Wrinkled and hasty, they were underwear and sheets, tied in fear and resignation. Resistance was out of the question.

In Hatim’s house, there was no time for comfort or worry. The rooms were hushed and urgent. His family acted quickly, their movements hastened by fear. “Yalla, bye,” his older brothers said gruffly, pushing gently past his father, who was paralyzed with powerlessness. Hatim knew there wasn’t time for a real goodbye. He didn’t try to stop his brothers from leaving, only watched his father’s face, frozen, pinched with pain, as his sons hurried out the door, fleeing to the east. Only Hatim and his brother Sharif remained, too young to be lined up. This scene was mirrored across the village, as able-bodied young men rushed out of back doors, quietly hoping to escape to the mountains. This day is remembered as Yom al Ihtilal, The Day of Occupation.

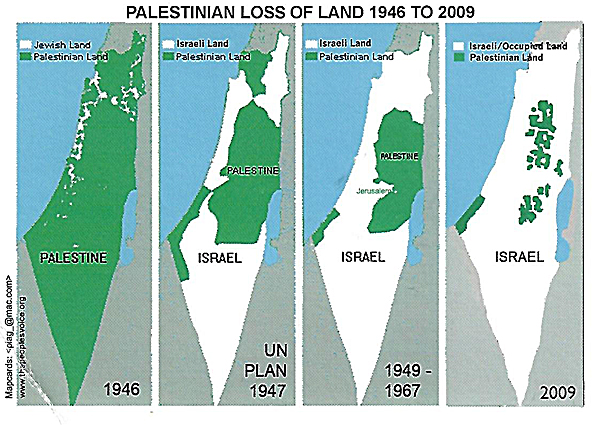

In May of 1948, the British Mandate formally ended and the establishment of the state of Israel was declared. A mish-mash of Arab forces declared war, and fighting intensified throughout the country. Hatim’s village would soon become engulfed by the new state of Israel. Around 400 Palestinian villages were emptied, and more than 700,000 people were forced to flee. A massive refugee population was born. Hatim’s village was one of the lucky few spared. Its residents, mostly Muslims and some Christians, became what would be seen as an ethnic minority in the new Jewish state.

Soon after the army trucks had crossed the dusty threshold into the village, a message rang out from the minaret of the mosque. The voice was familiar, the voice of the town crier who would announce if someone lost a goat, but the words were alien. “All the men gather in the marah,” he cried. “Kul el rjal, ijtimu fil marah.”

The marah, meaning the resting place, was a square farther down the village, the place where the working animals would gather every morning so the cowherd could take them to the pasture. The cowherd was paid in home-cooked meals from each family whose animals he tended. The daughter of the cowherd was Hatim’s age. Every night, she would come, bringing a bucket, and Hatim would go inside to get some of the food his mother and sister were cooking. The girl would leave with lentils and bulgur, or roasted eggplant and potatoes, and always some warm bread.

The remaining men of the village were herded into the resting place of the cows. Hatim thought of his brothers, already deep in the foothills behind them. Much of the village followed, sitting and standing around the square. One soldier lay on the ground, aiming a machine gun at the assembled men. The midday sun glared meanly onto the tops of nervous heads, bouncing off the barrels of weapons. Sweat gathered as the afternoon drew on, the air thick with hushed fear and whispers of reassurance. At last, one of the officers began to select the youngest able-bodied men in the square. He ordered them to stand against the wall, and the man on the floor turned his gun towards them. Everyone waited for what was going to happen.

Hatim, in the shade of an olive tree, kicked gently at the ground. Children from all over the village milled around in the olive fields bordering the edge of the marah. They were afraid, of course, but could not help being curious, only feeling the full gravity of the day in flashes, unable to reconcile their childhoods with the guns in the square.

Adults, with stony faces, tried to drive Hatim and his playmates away. “Get away from here,” they whispered forcefully, moving as if their bodies could guard the children from what was taking place in the square. But with their parents preoccupied, the children remained beneath the olives.

“When talk of leaving began, people started to turn to Hatim’s father, looking to him for answers: should we leave or not?”

Another army truck approached from the west, and then another. The soldiers corralled the men lined up against the wall and forced them into the new trucks. Their engines started up, and they drove away one by one. Nobody knew where the men were going, or what was next. Hatim watched his father, protected by his old body, too sickly and diabetic to be taken away. He wasn’t material for labor.

The day continued, a hum of muffled speech broken by angry cries. Unwaning, the tension began to reach the children, and Hatim sat quietly with his back against a gnarled olive tree, its roots over a thousand years old. The soldier’s departure was abrupt, ending the warm purgatory of the marah and beginning another, longer period of uncertainty and fear. The military occupation would formally last for eighteen years, later becoming a less visible system of oppression.

Earlier that summer, everybody had been preparing to leave, to take refuge in Lebanon. Families believed that this would be a temporary trip: go for a while until the war and its uncertainties receded, and then return home, to life. Of course, that never happened for those who left. For months, people had been trickling through Arrabeh on their way north to safer ground. One morning, as the sun was beginning to rise, Hatim was walking to get fresh water for breakfast. His footsteps slowed as he saw bodies lying beneath the olive trees where he often played. They were sleeping, families from the southern village of Safuryeh, wrapped in blankets. They waited for morning to continue on to Lebanon, leaving behind a child who could no longer walk.

Hatim’s father was a very level-headed man. He was respected throughout the village and had earned a reputation for being trustworthy. All his life, old ladies who didn’t trust anyone with their money would leave it with him, to hold it for them until they needed it. So when talk of leaving began, people started to turn to Hatim’s father, looking to him for answers: should we leave or not?

Hatim’s father kept replying, “wait,” “wait,” “wait.” As the urgency grew, and his family began to pack their valuables, folding blankets and preparing food, Hatim couldn’t get rid of one thought. He didn’t want to leave his birds. That May, the week his home was renamed the state of Israel, Hatim had stumbled upon a pair of small blackbirds nested in an apricot tree belonging to his father. He kept them, talking to them always around dusk, his 11-year-old palms stroking inky feathers. That year Hatim did not have school because the jaysh al inqadh, “the salvation army,” had taken the small village school as their headquarters. As the ragtag Arab army did weapons practice in his classroom, Hatim began to spend more time with his birds.

At the height of July, looking out the window of his house, Hatim contemplated his problem. Should he take them with the family to Lebanon, or would he have to let them go? Would they be okay, alone while he was gone? This question consumed Hatim as people began to return from the north. Resting after days on foot, sipping coffee in small circles, they brought word that the borders had closed. They could no longer reach Lebanon. Their window had closed. The land around Arrabeh began to feel smaller and smaller, as surrounding villages were occupied and borders were sealed off. Arrabeh was isolated and trapped, waiting for its turn.

“People felt defeated, any possible resistance was suppressed easily by an atmosphere heavy with fear.”

Early evening arrived, and the people in the marah began to disperse. Hatim’s father opened the door to a familiar face. It was Hayim Batata, meaning Potato. Everyone in the village knew and had done business with Batata, a cow trader from a nearby Jewish kibbutz. He had been a trusted and welcome figure. It turned out that Batata was now a commander in the Israeli armed forces. Standing in the doorway, he explained, gruffly, that he had received information that Hatim’s cousin owned a gun. He demanded that the cousin retrieve it, sitting down with Hatim’s father on two chairs facing the main street to wait for the weapon to be surrendered.

Every day, a car or a jeep would enter the village, carrying the commander in charge of the area as well as three or four of the soldiers. Often they knew about a gun that had not been brought forward. It was soon revealed that the army had many informers, often with close relationships to the villagers. The knowledge that they were being surveilled quickly heightened the growing wariness that pervaded the region. A standard reconnaissance process was replicated throughout the Galilee. Information came from people masquerading as salesmen and friends. Before an invasion, such an informer would gather thorough and specific information about who lived in the village. How many kids did each family have? Where did they work? Who owned what? This intelligence was relayed to army commanders, who used it to ensure that resistance could be easily quelled.

The cousin did not return for many minutes, and Hayem Batata, the friendly cow trader, grew impatient. He began to threaten Hatim’s father. Hatim drew behind an older uncle, hearing the insults echo through the street as men from the family looked on, powerless. The thought of the army truck resting in the square made people hold back their pride. Batata’s hand rose, and Hatim and his younger brother watched as the man’s hand swung through the heat to slap their father. Hatim felt his own cheek sting, his eyes burn. His Father’s hatta wa-aqal, the traditional headdress, an important symbol of honor, fell with a light thud into the dust. Eventually the nephew brought the gun, and Batata and the soldiers took it and left.

As it became clear that there were informers in the village, some people attempted to befriend the source of power. Villagers sought better treatment, a status that exempted them from indignity. Animosity towards these men never fully bubbled over, fear of reprisal maintaining a careful silence. No one dared cut ties with them. People felt defeated, any possible resistance was suppressed easily by an atmosphere heavy with fear.

The night that the army came, quiet thoughts swirled through the dusty village, banging up against windows, shuttered despite the heat. Where were their sons and brothers? Would they be killed? What would happen when the sun rose? As dusk arrived, the Israeli soldiers began to collect work animals from throughout the village. They herded the cows, bulls, and sheep through the main square, to the courtyard that belonged to Hatim’s family. The courtyard was enclosed by a low stone wall, a small metal gate funneling the cattle in. It was a long process, continuing after the light had dwindled, stubborn or hidden bulls found and then reluctantly guided through the twisting village streets. By late evening, the courtyard was packed and loud; cows crowded together, snout to tail, surging and jostling, bathed in their own powerful odor. Hatim, watching from the windows of his home, felt thankful that his family did not own any cows.

A woman from Deir Hanna, a neighboring village, knelt in the manure-coated earth, holding a soft, old cow. The woman’s arms did not make it around the girth of her animal; her fingers dug gently into the cow’s round sides. In the midst of the animals’ pungency, their pressed noise, a loud human sound emerged. The woman from Deir Hanna was calling the name of her cow, Hamami, meaning pigeon. She approached the soldiers, begging them to release Hamami, but was rebuffed again and again. Desperate, she came to Hatim’s father. She pleaded with him to interfere, but he could not, having already been dismissed and humiliated by the sweating, rigid soldiers. The woman sat by her cow deep into the night, singing frakkyat, separation songs, a genre likened to the American blues. Her voice rang in Hatim’s ears as his family’s long-ago-planted, just-ripening-for-the-summer pomegranates were trampled by the restless, tightly packed cows in the courtyard.

“Hatim’s sisters and mother braided the woman’s white hair long after the sunset, uttering words of consolation. “God will give you a replacement.” “

At dinner, Hatim’s family brought the woman from Deir Hanna in to eat, Hamami left alone with hundreds of other cows. There was no conversation in the dim room, hot air and the powerful smell of cattle washing in through open windows. Hatim’s family sat on cushions on the ground. They ate without speaking, their words displaced by the woman’s singing and the agitated, incessant chorus of moos outside. As her cries lapsed, her throat hoarse, the woman explained that Hamami was her livelihood, the only family she had. Tears streamed down her face as she whispered the word binti, my daughter. Hatim’s feet, tucked below him as he ate slowly, felt very heavy. His eyelids, too, began to droop as the woman pled with his father, addressing him in the formal way, as Abu Mohammed. “I can’t help you. You saw what they did to me when I tried.”

Hatim’s sisters and mother braided the woman’s white hair long after the sunset, uttering words of consolation. “God will give you a replacement.”

The next morning, the army came with trucks to load the cows. They would eventually be used to feed Israeli troops. They began early, as the sky hovered above darkness and Hatim packed food and water for his brothers in the mountains. Soldiers dragged wooden planks to the backs of the trucks, whose ramps quivered under the belligerent bulls and cows. Hatim watched in the pre-morning light as a soldier methodically twisted each cow’s tail, driving it into the gaping mouth of the vehicle. He stood still at his window as a fist closed around Hamami’s white tail, and a slight jerk, which Hatim did not see, his eyes suddenly blinking, caused her to run nervously up the ramp into the nearly full truck. Hatim heard her hooves skid across the plank for a moment, then she was absorbed into the crowd of waiting cows.

——————

Hatim’s heart beat steadily, slightly above its normal rate, swollen with more than the hike. Only two days had passed since the soldiers’ arrival. The hills rolled around him, olive trees Hatim played beneath huddled at the feet. He was past the green clusters, the hillside growing sparser the farther he ascended. Hatim’s stomach and chest fluttered, lifted from the quiet fear of his village. He was important, trusted, determined. Hatim did not think of his aching soles or of his blackbirds in their cage. He felt very grown, desperately needed. Below him, the village stirred, and everything was shifted. White flags of surrender, unnecessary undergarments, hung limp in the dawn. His brothers waited somewhere in the hills before him. Hatim looked forward, filled with a sense of duty, and continued to climb.