The looming threat of yet another mass expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland is ever present, especially today.

Although Nakba is often translated as “catastrophe,” truthfully there is no accurate translation of the word.

After all, how does one translate the attempted murder and destruction of an entire people? Whole families, homes, villages and towns, erased, gone. How does one translate massacres like Tantoura’s, where Palestinian children watched as their fathers were lined up and shot before being thrown in a large pit—a pit they were forced to dig hours before their death?

How do you translate Deir Yassin, where nearly every Palestinian was killed, women raped, and then burnt in their homes? Or Palestinian villages where Israeli commanders placed a bomb next to every home and then detonated the bombs all at once?

Here, Maj. Gen. (res.) Elad Peled recounts the events of the day to Israeli historian Boaz Lev Tov:

“What happened there, we came, we entered the village, planted a bomb next to every house, and afterward Homesh blew on a trumpet, because we didn’t have radios, and that was the signal [for our forces] to leave. We’re running in reverse, the sappers stay, they pull, it’s all primitive. They light the fuse or pull the detonator and all those houses are gone.”

Golda Meir, one of the prominent Zionist leaders and architects of the 1948 ethnic cleansing, walked into the city of Haifa only days after Jewish militia raided the city and expelled its inhabitants under threat of death within hours. In her journal, she recounts the horror and destruction she witnessed. In his book, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Ilan Pappe details Meir’s reaction:

“She at first found it hard to suppress a feeling of horror when she entered homes where cooked food still stood on the tables, children had left toys and books on the floor, and life appeared to have frozen in an instant. Meir had come to Palestine from the U.S., where her family had fled in the wake of pogroms in Russia, and the sights she witnessed that day reminded her of the worst stories her family had told her about the Russian brutality against Jews decades earlier.”

Twenty years after this, she became the fourth prime minister of Israel.

In many mainstream history books, historians portray the Nakba as a “war” between two equal sides and either justify or ignore the massacres and displacement that accompanied the founding of the Israeli state. This argument on its own should give readers pause: no massacre, no displacement of an entire people should ever be justified regardless of the context under which it occurred.

Still, even following this skewed rationale, the argument falls flat—there were not two warring sides. There was an occupying foreign power and an indigenous population defending itself. There were two sides only insofar as there was an oppressor, a colonizing army; and an oppressed, a native population defending their homes, their families, and their land. Not only were the Zionist militia better armed, in the years leading up to 1948, they received tactical and military training by British troops.

Thus the absurdity of the Zionist saying that Palestine was “a land without a people for a people without a land.” Every Zionist knew that the main obstacle to founding their state was that the land they wanted for themselves was already inhabited. Arab Palestine was a flourishing society with a long-standing history and culture. There were over 1,000 villages, thriving towns, abundant citrus and olive groves, irrigation systems, crafts, and textiles. Zionists had to obliterate all traces of this society if they were to build a new one. As the Israeli Defense Minister, Moshe Dayan, admitted in a speech to Israeli students in 1969:

“We came here to a country that was populated by Arabs, and we are building here a Hebrew, Jewish state. Instead of Arab villages, Jewish villages were established. You do not even know the names of these villages and I do not blame you, because these geography books no longer exist. Not only the books, but all the villages do not exist.”

Nahalal was established in place of Mahalul, Gevat in place of Jibta, Sarid in the place of Hanifas and Kafr Yehoushu’a in the place of Tel Shamam. There is not a single Jewish settlement not established in the place of a former Arab village.

The Palestinian Nakba is not only the compilation of the massacres of 1948 and the subsequent establishment of an Israeli state, but the occupation of land, the erasure of its people, and the physical and cultural attempt to destroy its history and identity. In this sense, the Nakba is reminiscent of the United States’ dispossession and erasure of indigenous Americans, from the colonization of “New England” to the Trail of Tears.

Much like oppression of Native Americans, the Palestinian Nakba is neither a distant occurrence nor completed history, and treating it as such only reproduces the Israeli contention that Palestine and Palestinians are romanticized representations of the past.

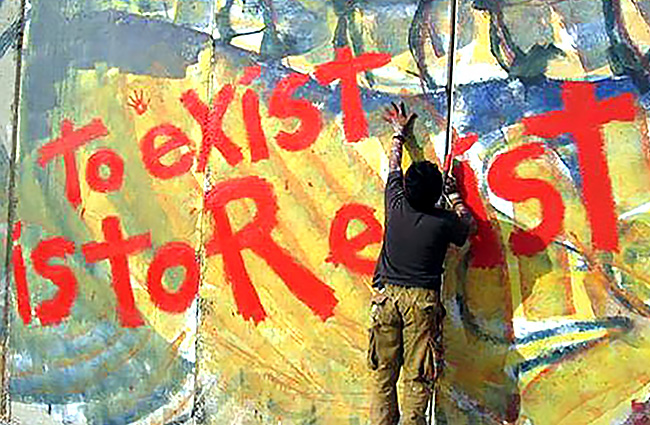

The Nakba is not situated fully in the past, nor is it fully in the present, but it transcends the notion of linear, progressive, and positivist history. It is a continuous and complex struggle against occupation, against apartheid, against erasure. It is the daily physical and abstract dispossession of land, identity, culture and history. It has not ended.

And for precisely this reason, the Israeli state has sought to penalize the remembrance of the Nakba. In 2011, Israel introduced the Nakba Law, which authorized the state to withhold funding from any public institution that mourns or commemorates the Nakba.

The looming threat of yet another mass expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland is ever present, especially today. The Nakba is just as present and significant as it was in 1948. Treating it as anything but is to succumb to Israel’s fabricated narrative of a long forgotten past from whence it has progressed. Naming and remembering the Nakba is the most basic precondition for building a movement that can effectively resist the racism and erasure at the heart of Israel’s settler-colonist project

Equally important as confronting the Nakba, however, is coming to terms with the historical developments that led to the crisis of 1948. Foremost among these developments is the emergence of Zionism and the Zionist movement, whose basic principles have given the Israeli state an enduring ideological justification for its colonization of Palestine.

(This excerpt of “Palestine: A Socialist Introduction,” by Sumaya Awad, is presented with permission from the author. For more information to order a copy, please visit Haymarket Books.)

Editor’s Note: This story is part of a series of writing about Palestine and Palestinians, written by Palestinian American writers, published in the wake of the Israeli government ordering the expulsion of Palestinian families in Sheikh Jarrah, which led to Israeli raids on Al-Aqsa Mosque compound and aerial bombardment of Gaza in May 2021.

You may also be interested in these related stories:

1948: An eleven-year-old boy was forced to grow up fast when occupying Israeli soldiers seized his tiny Palestinian village.

Rites of Return: What does it mean for a Palestinian living in the United States to resist?

Broken Ghazal, Before Balfour: Two Poems by George Abraham