Relaunching the Black and Asian Feminist Solidarities column with a conversation with the author of Concentrate.

May 10, 2023

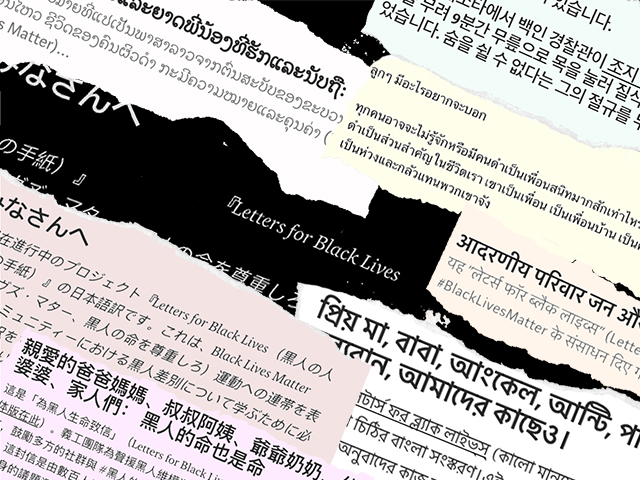

The Margins’ Black and Asian Feminist Solidarities column relaunches today with an essay titled “Five Memorials for Latasha” by poet and writer Courtney Faye Taylor, excerpted from her book, Concentrate (Graywolf Press, 2022). In her essay, Taylor commits to the act of memorializing Latasha Harlins, a fifteen-year-old Black girl who was killed by Korean American convenience store owner Soon Ja Du on March 16, 1991. Taylor remembers Harlins by visiting five locations in Los Angeles crucial to her life, death, and memory.

Thirty-two years after Harlins’s murder, we still see Black youth typecast as criminals and victimized by gun violence for no reason other than blatant racism. In Ralph Yarl’s case, ringing a doorbell as a sixteen-year-old Black boy was enough of a threat to his assailant to warrant a bullet in the head. In Harlins’s case, being suspected of shoplifting a $1.79 bottle of orange juice as a fifteen-year-old Black girl was enough reason for Du to shoot her in the back of the head.

Harlins’s life mattered, and her memory is important to our understanding of Black and Asian solidarity—her shooting is a touchpoint in a long history of Black-Asian conflict in America. We still mourn Harlin’s death and pay tribute to her life. We still pick apart Du’s motives and where cross-racial relations crumble and rupture.

“Five Memorials for Latasha” serves as a perfect reminder today of the tensions that have existed between our communities, the radical act of remembering, and the dangers of forgetting. Taylor gives The Margins insight into her process of writing this essay and reflections on memory, erasure, and Black and Asian feminist solidarity.

Tiffany Diane Tso (TDT)

What prompted your investigation into the killing of Latasha Harlins and the different landmarks of her life and death?

Courtney Faye Taylor (CFT)

Concentrate began as a curiosity about tensions between Black and Asian American communities. I was looking at Black beauty supply stores as a location for this conflict, but the murder of Latasha Harlins kept coming up. Though her murder took place in a convenience store, it’s one of the major historical events that illustrates our tension.

At first, all I knew of Latasha was her death, but then I learned about her childhood—across the span of fifteen years, she was a dancer, a poet, a sister, a survivor. In LA, I saw the places her life touched. In writing about her, I wanted to affirm the ways she touched the world and left an irreversible mark, an incredible impact.

TDT

In your piece, you make several references to “Looking for Zora,” an article in which writer Alice Walker visits Zora Neale Hurston’s birthplace to search for her unmarked grave. Did this piece provide inspiration for “Five Memorials for Latasha”?

CFT

When I got back from LA, I told a friend about my attempt to find Latasha Harlins. This friend recommended I read “Looking for Zora.” I was moved by the similarities between Walker’s search for Zora’s burial site and my search for Latasha’s headstone. The essay reframed my perspective on that journey. Through Walker, I recognized my writing as an intentional act of resurrection, too—resurrecting memory, resurrecting history, resurrecting our empathy and respect for Black identity.

TDT

The themes of memory, memorial, loss, and forgetting resonate throughout your essay—remembering and memorializing can be a radical act. How does this work fit into your own feminist praxis?

CFT

I’ve been thinking a lot about anti-erasure as the foundation of my feminist practice. I want my work to stand in opposition to systems that require the erasure of Black women and femmes in order to thrive. In Concentrate, I do that work through memorialization, since one of the ways white supremacy dominates us is by ensuring we forget our own subjugation. In Concentrate, I’m asking myself and my readers to remember. But in the wake of memory comes the question of what to do with it. Where do we go with the knowledge of what’s happened to us? For me, the answer was to go inward. By remembering Latasha, I remembered myself, I remembered the possibilities of Black girlhood despite its risks.

TDT

What different emotions came up while you were on the journey of writing this piece?

CFT

I didn’t realize how much this trip would move me, and I had no idea it would find its way into my writing. I initially went to LA to, as I say in the first part of the essay, work through the imposter syndrome I had about writing into this topic. I thought being in these places would give me certainty about what I knew. But it gave me more—it sparked a deeper consideration of the similarities between Latasha and me, Latasha and many Black girls I’ve known. Coming across the mural of Latasha and realizing that she was a poet, too, allowed me to see our lives as mirrors. It’s emotional to see myself in Latasha’s story. I don’t think I would’ve seen that parallel as clearly had I not stood in the places where she lived.

TDT

How does “Five Memorials for Latasha” fit in with the rest of Concentrate? What other topics and themes do you explore?

CFT

“Five Memorials” sits in the middle of the book. I think of it as breaking the fourth wall of the collection. It’s the point where I, as the author, speak up to say, “These landmarks are central to our memory of Latasha, and thirty years later, she still exists here—in graffiti, in murals, in headstones.” The rest of Concentrate holds space for Black womanhood and girlhood more largely, stepping into both its precarity and its unparalleled beauty. That duality—the celebration and the mourning—feels inseparable.

TDT

You have mentioned that in writing Concentrate, you have worked to “consider the ways Black and Korean American women navigate a similar terrain of vulnerability in this country.” Can you speak more to what that looks like? Is there possibility for solidarity within that “similar terrain”?

CFT

Latasha Harlins and Soon Ja Du lived under white supremacist patriarchy. Though Soon Ja is responsible for an indefensible act of racial violence, there’s also the reality of her and Latasha’s marginality and their identities as survivors of male violence. I have a section in Concentrate that looks at sexual and physical violence to give space to this truth. It’s my hope that this excavates that “terrain of vulnerability,” a terrain on which solidarity must be formed. But what I emphasize in Concentrate is that not only is solidarity a possibility, it’s a reality. There’s a long history of unity between Black and Asian American communities. In LA, there were organizations like the Black-Korean Alliance that were active before the uprisings. It’s part of white supremacy’s objective to get us to disbelieve that history, to desert our togetherness.