Writers share the books they have turned to when imagining a world without without cages

March 5, 2021

Our ideas and visions for alternative futures emerge through ongoing processes of learning, discussion, and practice. Fred Moten highlights how study is a political activity, a practice of studying together outside of or in spite of institutions and a refusal of a “call to order.” Abolitionist Stevie Wilson has spoken about the importance of study, describing study as central to prison disorganizing. Writers and organizers from our A World Without Cages project share the books they have shaped their imaginations, deepened their analysis of carceral systems, and inspired them to build different possible worlds.

—Rachel Kuo

Editor, A World Without Cages

geunsaeng (olivia) ahn

author of “Abolition is Not a One Time Event: Prison Doulas as Catalysts”

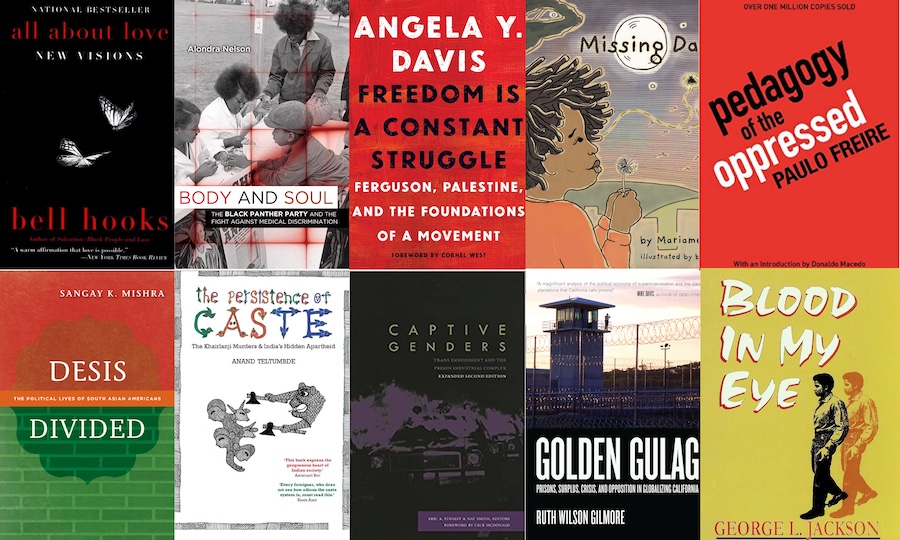

all about love by bell hooks (2001)

This was one of the first Black feminist texts I ever read, and it absolutely changed my life at a time when I needed it most. I return to this book often and read it at least once every year. It continues to bring me profound new experiences, insights, and meanings, wherever I am, and whatever I or my community, my family, my kindred, is/are going through. It encourages me to love again, and again, and again. hooks powerfully articulates love as an element, an ethic, and a radical practice that must exist at the core of any abolitionist framework. hooks proposes love as something that is not conditional, nor unconditional, but deeply transformative if we truly allow it to be. It requires us to relinquish control of each other and of ourselves: to free each other through love. To love is to disavow the social conditioning that our oppressors have taught us to perpetuate against each other. To love is to constantly and consciously commit and recommit to our collective liberation. As hooks names, “Love as the practice of freedom.”

This book exemplifies of Black Liberation as collective liberation. Nelson shows us the history of how the Black Panther Party founded what has now become the (common/co-opted) discourse of “healthcare for all” in the U.S. Body and Soul provides a deeper dive and chronology of the Panthers’ community service and accountability efforts, specifically their free health clinics and programs that addressed anti-Black racism and medical violence, which still exists in health care. The legacies they left behind through the clinics they formed still exist today, even though the nation’s collective amnesia and criminalization of the Black Panther Party has remained. This book is a blueprint that should be used to continue the legacy of what they created and shows us what is possible through collective “community care [that] requires societal transformation.”

Havannah Tran

author of “Where No One Suffers Hungry”

Golden Gulag by scholar and abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore should be required reading for any resident of California. Wilson explains the origins of the state prison system and the 500% boom in the incarcerated population between 1982 and 2000. In the introduction, she writes “While common sense suggests a natural connection between ‘crime’ and ‘prison’, what counts as a crime in fact changes, and what happens to people convicted of crimes does not, in all times and places, result in prison sentences.” This particular line stuck with me as I learn to understand how we are all capable of harm, but only some of us are deemed criminal, oftentimes determined by white supremacist logic. Wilson’s research is expansive and implicates all of us in upholding carceral logic and systems. She reveals that California’s financial wealth is tied to prison labor, aided by the intentional fracturing of communities. I can’t imagine finishing this book, left to reflect on what harm we’ve intentionally or intentionally enacted, and not immediately be moved to action. We are all responsible for these cages, so we all better tear them down.

Luna Ranjit

author of “Memory”

Freedom is a Constant Struggle by Angela Y. Davis (2015)

The title of the book is drawn from a freedom song from the southern United States, with the refrain “we must be free, we must be free.” In this collection of speeches, interviews, and an essay, Davis centers the importance of Black feminism and Black radical traditions, along with stories from around the world to show how struggles against state violence and oppression are connected from Ferguson to Palestine, from South Africa to Turkey. Davis highlights how in 2014, Palestinians tweeted advice to the protestors in Ferguson after recognizing the stamp on tear-gas canisters, produced by a US company called Combined Systems, Incorporated—an example of “horizontal continuities” of both oppression and resistance. She also shares how the global security company G4S, the third largest corporation in the world, profits from the Israeli occupation of Palestine; caging and transporting undocumented immigrants; and providing weapons to armies as well as running centers for abused women and “at risk” girls. G4S uniforms are often seen in the streets of Kathmandu as well. The book ends on an optimistic note that “increasingly, young activists are learning to acknowledge the intersections.”

I came across this book at the moment when I was feeling frustrated with the pervasiveness of American exceptionalism, including in left movement spaces. Of course, the book does not cover all the geographies and issues I support or I am learning about. No one book or an individual can do that, definitely not in a meaningful way. What this book does give me is a lens and a roadmap, a transnational framework of understanding the “spatial and temporal connections” of struggles to build transnational solidarities. I have carried this slim volume with me from New York to Kathmandu, back and forth multiple times, flipping through it whenever I need words of inspiration.

Monica Mai

author of “When I am Warm I am Safe”

Missing Daddy by Mariame Kaba (2018)

Mariame Kaba has been monumental in my abolitionist learning and becoming. It all started with this beautifully illustrated picture book about a young girl who misses her dad in prison. I first came across this when I was doing research for my senior thesis (a short film lightly informed by personal memories of my dad’s incarceration), and I was so overjoyed to discover that there now exists such a resource for children with incarcerated loved ones. There were no resources available to me when I was younger, so reading it when I did felt like someone was, at last, consoling my inner child.

“Abolition is not some distant future but something we create in every moment when we say no to the traps of empire and say yes to the nourishing possibilities dreamed of and practiced by our ancestors and friends… abolition is about breaking down things that oppress and building up things that nourish. Abolition is the practice of transformation in the here and now and the ever after.” This is an incredible collection of writing from people on the inside, with a focus on the experiences of incarcerated trans, queer, and gender non-conforming people. When I first learned of abolition, I was skeptical—I didn’t know how to imagine safety without the carceral state. I thought abolition was some far-off fantasy idea, but reading and re-reading this really grounded me in abolitionist ways of thinking and being. Abolition must be possible because it is the only avenue of liberation from state-sanctioned violence; there can be no compromise for freedom and liberation. These writings show how abolition is so intimately linked to queer liberation and the destruction of all systems of oppression, and I am reminded that a better world can and must exist!

Mon M.

author of “South Asians for Abolition: Beyond Gilded Cages” and with Sharmin Hossain “South Asians for Abolition: Diasporic Strategies and Conversations”

Desis Divided: The Political Lives of South Asian Americans by Sangay K. Mishra (2016)

This book is a great survey of South Asians in the US diaspora for someone looking for a starter bit of reading. Sangay Mishra traces the history of South Asian immigration from its fraught beginnings to its imminent realizations, including histories that are sometimes deliberately erased or forgotten. Specifically, his analysis is great for someone looking for an introduction to South Asian American political participation within the US, beginning with the journey to the US, the formation of a South Asian identity associated with the regionality of Silicon Valley, the post 9-11 resistance — particularly among South Asian Muslims – and the ongoing advent of diasporic nationalism. In particular, Sangay casts his eye on South Asian communities as historically and inherently “divided” by caste, religion, class, ethnicity, race, gender, and more. I would say that this book should be supplemented by critical writing on race, gender, and caste by Dalit, adivasi, Muslim, and women South Asian writers. This is because the broad strokes documentation of South Asian political participation in the U.S., as in the case of Mishra’s book, often leaves out the details of how communal divisions among South Asians reflect erasures.

The Persistence of Caste: The Khairlanji Murders and India’s Hidden Apartheid by Anand Teltumbde (2010)

Excerpted from Mon’s piece here: “Abolition in the US is contingent on liberation everywhere. South Asian abolitionists from all backgrounds, but especially those who are North Indian, dominant caste, cis or straight, need to recognize the interdependency of these struggles and look beyond the U.S., beyond India, where these battles against caste, religious, and racial violence are being waged.”

Michael “Safear” Ness

author of “The Home I Dream”

Blood in My Eye by George Jackson (1972)

Reflections on doing revolutionary readings in an alternate reality: Some people make it home and some people die in here. We sat on the bench as my comrade recited Blood in My Eye, the sacred text. I followed his words along the pages of my handwritten copy. Steel gates and razor wire boxed us in the yard. Trash talkers cracked jokes at the card table while the muscle heads hammered metal in the weight pit. Don’t let the smiles fool you. None of us wanted to be here, but the revolution had stalled at the prison gates. Our only hope now was the sacred text. Jackson writes, “One has to understand that the fascist arrangement tolerates the existence of no valid revolutionary activity.”

My comrade stopped reading and I looked up from the book. It took a moment to comprehend what I saw, the sight was completely out of place – an army tank was storming at the prison gates. Sharp shouts pierced the silence, bringing us to our feet. The C.O.s’ arms flailed around like drowning victims trying to command the tank to stop. The thought to run crossed my mind, but I knew the tank was there to free me or kill me. The tank stopped in front of me, bringing the smell of gunpowder. A person’s head appeared. Maybe it was the sun’s rays, but I could have sworn I saw a halo shining above it. A man lifted himself out of the hatch and jumped off the tank. My comrade could barely get out the words.

“G-george?” he asked.

The man smiled. It was George Jackson.

“What the hell’s going on?” My comrade asked.

George pointed toward the sacred text in my hand.

“I heard your call” he said.

Pedagogy Of The Oppressed by Paulo Freire

Everybody eats. If you’re ever in prison and you need to cook some food, you will probably have to use a stinger. First, you fill a plastic bucket with water and pour some salt in it. Next, you cut the end of an extension cord (or the stolen plug from the back of a TV), separate the two wires, and attach a broken nail clipper piece to each end. Put those ends in the bucket of water, do not let those ends touch. Then, finally plug the extension cord into a socket or a light switch. After a few minutes that water will be boiling.

I learned that from the people. One of the most important characteristics of the revolutionary is the ability to improvise. The people know how to improvise. If we are serious about mobilizing the people, then we have to get down in the trenches with the people, learn from the people, and learn with the people. Yes, learn with the people. Not looking down on the people from thrones of academia thinking you have it all figured out, thinking you have to swoop in with your nonprofit and save the people from their oppression. It just might be that the people know more than you, that the people can teach you a thing or two. Freire wrote, “Solidarity requires that one enter into the situation of those with whom one is solidarity; it is a radical posture.”

So, as you sit in your armchair, developing your theory, we are here in the undercommons, in the trenches. Not just seeking knowledge for the sake of knowledge, we are using knowledge as a weapon to change the world. You are welcome to come join us, but don’t come here thinking you’re going to save us. It just may be that we are the ones who will save you.

Or maybe one day, before the world ends, we can save each other.