One writers group was robbed at gunpoint in Ditmas Park. The police and the community’s reactions were swift, but both seemed to miss the bigger picture.

October 1, 2015

We had been workshopping Jennifer Chowdhury’s piece when a man came right into our little room from busy Church Avenue. It was November, so by the time my writing group met at 7 o’clock, the other side of the glass was just darkness. We couldn’t see passersby and we didn’t think much of them seeing us.

Our group met routinely on Thursdays at Lark Cafe in Ditmas Park, in a small annex attached to the coffee shop. Each week I looked forward to class, a night less about my work and more about being a part of a group of radical writers with whom I feel a deep sense of community.

Most of us are women, children of immigrants, queer, people of color, from working-class backgrounds around New York, or all those things combined. We share a spirit of rebellion and a profound commitment to challenging mainstream narratives. Our meetings provide a moment for us to shut everything else out and share our craft and personal stories with honesty and vulnerability, away from the harshness of the rest of the world.

I assumed the stranger was a vendor stopping into businesses, maybe even a high school kid selling candy. Soniya Munshi, sitting to my right, later said she thought the same thing — DVDs, maybe flowers. But then, he swiftly crossed the space between the door and our table and pulled out the gun. A silver revolver held level with our faces. It happened so fast that the image of the candy-seller didn’t quite evaporate. I thought it was a joke.

He placed a black nylon drawstring sack on the table.

“Put the computers in the bag,” he demanded, through a mask covering the bottom half of his face.

I looked around. All nine of us were frozen, mute. But then he said it again and added, “Quickly! I don’t want to kill anyone.” He waved the gun around a little.

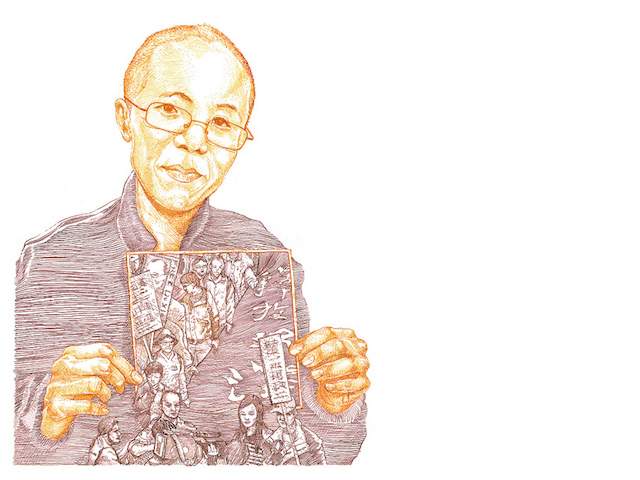

Across the table, our instructor, Bushra Rehman, rolled her eyes, and, with an exasperated shake of her head, shut her MacBook. I took that as a cue and followed suit. Those of us with devices out and visible — me, Bushra, Soniya, and Jennifer with her iPad — handed them over. Bushra put everything in the bag; he grabbed it and was gone. Likely in under a minute.

Then, as the rest of us took a moment to grasp what had happened, Bushra did the thing that made sense: she called the police.

____________________

The next day, The New York Times reported on the incident, placing it in context of other robberies that had occurred in “the normally quiet neighborhood of Ditmas Park” in the weeks prior.

The article noted, “business owners speculated that the new wealth was pushing up against older poverty and creating crimes of opportunity or even hostility.”

The lead described the theft of our belongings:

The group of writers met at the trendy Brooklyn cafe as they did each week, to talk about their works in progress. Surely none of them, during discussions of character and twists of plot, guessed that a masked gunman would barge into their circle on Thursday night and rob them of their laptops.

And yet.

One minute the writers were sipping coffee. The next they had their hands in the air. The gunman left carrying several laptops, stuffed in one writer’s tote bag.

None of us who had been present for the robbery were interviewed. The details of the scene were factually incorrect — the hands-up stance as well as the tote bag were fabricated — but it created the right amount of drama to serve a story that depicted us as clueless victims of a dangerous gangster.

“We were made invisible by Mosi Secret’s article,” Bushra said, referring to the reporter who wrote the NYT story. “He kind of had a mocking tone toward us; it’s really subtle, but it’s definitely there. [A friend] was like, ‘Yeah, if I didn’t know you and I read that New York Times article, I probably would think you were just some privileged trust fund-y hipster sitting around drinking your expensive coffee and having the whole day to just hang out writing.’”

“Being wary of how fear gets used in these situations and understanding the relationship between fear and gentrification and policing, and all the things I know about those links that get made, I think there was a little bit of disappointment in myself.”

The racial implications in the piece are apparent. And though the tone acknowledges that perhaps we are not naive innocents in a crime where “edges clash,” it nonetheless fuels a notion that poor to modest neighborhoods of color are full of hooded thugs, and that outsiders moving in, typically whiter and more affluent, are in need of protection from the rough culture of their new surroundings. But looking at things through a slower lens reveals a more complex reality of such places in transition.

When I contacted Secret later to ask how the story had come together, he said that he had arrived on the scene at 3 p.m. and had to file his story by 6 p.m. In that short time, in a neighborhood he did not know well, he followed the lead of the locals he was able to interview. He attempted to reach Bushra, but was unable to speak to her before he filed.

“I would actually tend to agree with you that more was made of this division than what I saw when I was walking around,” he told me.

The parts of the story that highlight sharp differences between homes and residents were quotes, he said, not his personal impressions. As a reporter, he relayed the sentiments of those with whom he spoke.

“An editor gives you an assignment and you parachute in, and in that situation, what you get is kind of what makes it,” Secret explained. “Given more time, you can develop more nuance.”

____________________

“I had a moment of being pretty panicked about the actual gun, but I was also frustrated with myself for that. it was almost like my body was scared but my mind wasn’t,” Soniya said, recalling her reactions to the man’s presence.

“Because I didn’t ultimately think that person posed a threat. I didn’t feel afraid of the person; I felt more just afraid of the weapon,” she said. “And being wary of how fear gets used in these situations and understanding the relationship between fear and gentrification and policing, and all the things I know about those links that get made, I think there was a little bit of disappointment in myself.”

Shock and trauma commonly follow an encounter with potential violence. But for many of us, what happened in the aftermath of the robbery troubled us more than the event itself.

After the robber left, we crowded into the cafe, rattled. The hush of our bewilderment built slowly into a frenzy as the baristas and few remaining customers heard what had gone down. The police arrived shortly. There were a lot of them; they had shown up in cars and swarmed near Lark’s entrance, scribbling in their notebooks and talking into their radios.

They asked us questions repeatedly but silenced us with, “One at a time!” They took our description of the robber, who had been in a black pullover hoodie, black track pants, gloves, and the mask. Naomi Gordon-Loebl, another writer in our group, said that one officer told her and Bushra that they couldn’t do things how they used to — whatever that meant.

While some of us who lost property gave them our information, someone came up with the idea that we might be able to track our devices through the Find My iPhone application, which works for all Apple products. I entered my Apple ID into the iPhone of one of the officers. Within seconds, the officer and I were able to see a blue dot moving across his screen. I remember it traveling east along Church Avenue and ultimately stopping around Lenox Road, either on Flatbush or Bedford Avenue.

Jennifer and I were randomly selected by some of the officers to go along with them to the location. We all assumed that the trip to the blue dot was an attempt to retrieve our equipment, not because we cared about the objects themselves, but because our dissertations, novels, poetry, memoirs, and more – a significant portion of our lives’ work – were in that bag. But when we arrived at a large apartment complex, two officers got out of the car, and nothing happened. We went back to the coffee shop.

He was young, black, and in a zip-up hooded sweatshirt. He was held still by an officer and his hands were behind his back.

Later, Detective Alfred Genao of the 70th Precinct, one of the officers present that night, explained the limits of what they could do at the moment. “We can’t just stop anyone anymore even if we suspect them of something; we need to actually see something happen,” he said. “So we went to that location, we had the descriptions that were given to us by the people at the establishment, and the most we could have done if we saw someone who maybe fit that description was talk to them and then see if they had the devices on them.”

He was with another detective, but neither of the saw anything they could act on, he said. “I’m sure that they were in a particular house there, but like I said, we can’t just knock down the door anymore.”

My sentiment, and that of the group, was that “catching the guy” was not the most important goal to us. We hoped for the return of our things and felt most poignantly the loss of our writing, which we have continued to grieve in the months since. We felt angry and violated, but not in a way that necessarily placed blame on the person who did it.

In the weeks that followed, we spent part of our workshop time healing and processing what had happened, thinking as the educators, social workers, journalists that we are. Finding space to take into consideration the broader social and economic circumstances surrounding the incident, we cultivated our sense of compassion toward the robber, whom we imagined must have been acting out of dire need. But finding a suspect was invariably the focus for the cops, and almost everyone we spoke with about the robbery asked: “did they get him?”

Back at Lark, Jennifer and I told the others what had happened. Minutes later, the two of us were ushered into separate unmarked vehicles to cruise around and possibly ID a suspect. Somehow, we ended up near the Prospect Park Parade Grounds on Parkside Avenue, nowhere near the location to which the devices had been tracked. Here, I was asked to look through a tinted window cracked open at a man who had been stopped on the dark, rainy street before we had arrived. He was young, black, and in a zip-up hooded sweatshirt. He was held still by an officer and his hands were behind his back. I thought I made brief eye contact with him, his expression knowing yet defeated, before I said, “No. I don’t know. I can’t say.”

They took me back to Lark again. Before I got out of the car, one of the officers handed me his phone with a photo open on the screen, a shot from a surveillance camera of another young man leaving a bodega. “Does this spark anything for you? Does he look familiar?”

He did not. And he looked nothing like the man on Parkside.

Inside, with the others, I began to cry. I had been driven around to see whether unlucky black strangers in hoodies could possibly be someone I was in the same room with for mere seconds, whose eyes had been his only visible facial feature, and whose hands were the only part of him I had really looked at.

Jennifer got pulled out one more time to check out another guy. She later said that the officer in the car she was taken in was aggressive with her, goading her to decide whether or not the individual could be our gunman, though she said she didn’t know.

“[The police] didn’t necessarily make me feel any safer,” Nina Sharma, another member of our group, said. “They weren’t very transparent about what their police work entailed. We gave the same information a few times to different officers. They told us there weren’t any ‘suspects’ but the police just stopped random black men on the street, that they were, in sum, stop-and-frisking.”

Nina thought of her husband. “He’s black and he’ll be not only walking, but rushing down these streets to get me. I got scared of what could happen to him.”

____________________

One thing that The New York Times and other media that covered the robbery did get right was that the incident shook up the Ditmas Park neighborhood and the surrounding community. Residents, business owners, civic leaders, and elected officials attended meetings in the weeks after to address what appeared to be a pattern of crimes popping up. In the month prior to the Lark Cafe robbery, there were armed robberies at Ox Cart Tavern, Mimi’s Hummus, a deli, and a T-Mobile store. At the meetings, the discussions centered around increased surveillance and policing.

At one gathering organized by the Flatbush Development Corporation, one businessman, Avi Shuker, called for additional police cameras and police presence. He owns three popular businesses that have opened on Cortelyou Road in the past six years: Mimi’s Hummus, the wine bar The Castello Plan and a quaint Italian restaurant called Lea. Others asked City Councilman Mathieu Eugene to invest in mechanical fixes such as more lighting on certain streets.

Deputy Inspector Richard DiBlasio, the commanding officer of the 70th Precinct (no relation to the mayor), reassured those present that the precinct had boosted patrols on Courtelyou, that more officers would be placed in the neighborhood’s commercial corridors during the holiday season, and that he guaranteed they were “going after the bad guys.”

At the Church Avenue Business Improvement District Annual Meeting, DiBlasio focused on identifying suspects and the importance of security systems. “We hope to get the perpetrators sooner or later, but I want everybody to rest assured that the 7-0 precinct is out there for you; we’re out there for the community,” he said. “We have a lot of foot posts now especially on Church Avenue just up the block. The impact zone is further down, but I’ve moved some police officers to this end to cover these food establishments.”

“Using police as a form of repression is not going to work. It’s not going to work. We need to address what truly is happening in our community.”

For the most part, locals listened patiently to the precinct’s plans. But one underlying issue, the same issue that all New York neighborhood discussions seem to circle back to these days, only came out in a town hall meeting at P.S. 139. The elephant in the room — the massive changes in the Ditmas Park, Flatbush, and Kensington neighborhoods due to rapid gentrification and those adversely affected by such changes — was finally called out by name. Some feared that crime levels could return to levels of a few decades ago, but the proposed solution to add more cops and cameras was hotly contested.

Alicia Boyd, one of the residents who spoke at the P.S. 139 meeting, told me that she and other residents are well aware of the complexities of the situation. “We understand the need for safety,” she said. “However, using police as a form of repression is not going to work. We need to address what truly is happening in our community — and that is the systematic removal of people of color from their homes with no place to go but shelters or doubling up.”

For Boyd, that was the crux of the matter. “And this is creating a very frightening and hostile environment and nobody’s really sitting down and looking at the relationships that are forming or what we need to be doing in order to ease some of the people’s anxieties, both the people who are coming in and the people who have been here. No one’s speaking about it. Instead it’s just, ‘Oh we need more policing’.”

Alicia founded the Movement to Protect the People in April 2014 to fight against a high-rise residential project at 626 Flatbush Avenue, as well as rezoning that will bring in more development to the area and likely accelerate the pace of change.

Long before these robberies became a front-and-center issue for some, she and other neighbors attended community board meetings to fight the prospect of 23-story complexes rising next to their low-rise limestone townhouses. She said they were surrounded by 25 to 30 armed police officers at the meetings. It wasn’t until December, when most of NYPD resources shifted to regulate protesters against police brutality in other parts of the city, that the number of officers assigned to the meetings decreased to two or three.

“That’s the theme: if we have any type of uprising or any type of pushback against gentrification, in any form that gentrification is transpiring, we’re going to bring the police in,” she said.

Imani Henry, of Equality for Flatbush, a people of color-led grassroots organization that does anti-police repression, affordable housing, and anti-gentrification work, added that the neighborhoods that have experienced highest rates of stop-and-frisk and broken windows policing are the ones that are most rapidly gentrifying.

A Brooklyn native born and raised, Alicia traced the history of the area. Before recent changes, she said that long-time residents fought hard to stabilize what were extremely violent neighborhoods. Battling crime in the ‘80s came in the form of people organizing themselves, staging demonstrations, pushing for better jobs, demanding better services from the city, and more. She emphasized that it was these community-based strategies — not law enforcement — that proved successful, and by the time she moved to the area in 1999, it was very safe.

Still, she did not dismiss the role of policing. But it can’t be only that, she said. What’s missing is an open dialogue, one which includes the existing community and which prioritizes their concerns and safety. While the newcomers may not feel they are taking over, that’s how existing residents view them. She stressed that without acknowledging that part of the picture and by looking for quick fixes, namely police action, we are collectively ignoring the root of the problem.

“I’m an educated woman, so I’m fighting back through petitioning and harassing my representatives and organizing the people and creating a website,” Alicia explained, adding that she assumes the people committing crimes are intentionally targeting new establishments and the customers who frequent them as their own way of fighting back against the danger of displacement.

“What would you do if you were part of the lower echelons of a culture, you were uneducated, you were barely making it, or you’ve been oppressed?” she asked. “I mean, racism is alive and well for black people in America. So here you are growing up in a community and, for good or for bad, this is your home, this is where you live, and all of a sudden there’s a more powerful element coming in and removing you. You’d use whatever power you feel like you have that’s available to you to help stop this. And if the only power you have is to be able to choose who you’re going to rob, you will exercise your power in that way.”

Alicia’s theory about the motive of the crimes may or may not be accurate, but the dynamics she describes certainly are.

____________________

The limitations of intensive policing, and the harm it can cause, rose to the surface for us in the circumstances surrounding our robbery. Granted, what we experienced was far down on the violence scale compared to what has come to light after the murders of Mike Brown, Eric Garner, Akai Gurley, and so many others before and since.

The protests that drew the NYPD away from meetings where folks such as Alicia spoke out have calmed a little. Yet the situation that led to them remains: that cops assault and kill black people with what looks like reckless abandon and impunity, that they can be videotaped doing so and authorities will construct a defense to justify their actions under the law. As long as this is the case, how can people of color look to police to stand for safety or protection where we live?

In the neighborhoods around Ditmas Park, residents old and new had opinions on how to respond to the robberies and how they ought to be investigated. Still, honing in so narrowly on the crimes, or even crime in general, causes us to miss the bigger injustice. Defenders of the process we have come to call gentrification understand it as positive urban renewal with the unfortunate cost of displacement and dispersal. But for many of us, it is a primal act of violence: when people are forcibly uprooted, they are made invisible and their humanity is erased.

“I feel like we have to ask the questions about safety differently, like, are we protecting people or are we protecting property?” said Soniya, one of the members of our group whose laptop was stolen and who lived in the neighborhood years ago. “Can we consider safety things like safety from the threat of losing your home because of rent hikes? If the conversation was framed around something like, ‘How do we ensure that people have security in their neighborhood, a sense that it’s their home and they can stay here?’, it would really change the other kinds of conversations we’re having about protection and what kind of resources we need in the area.”

These kinds of questions rarely get raised in public forums, or in the media. They typically only circulate among educated, like-minded people intent on social justice analysis. My own perspectives on this singular crime that affected me individually, and how it fits in a broader context, are multiple and difficult to reconcile. I think frequently about another question people asked me a lot about the crime: “Was he black?”

As a person invested in racial justice, I’m mindful of how the criminalization, degradation, and dehumanization of Black people is woven into our culture and our legal institutions. As a South Asian American woman who has recently moved into the neighborhood but is currently facing a rent increase that might push me out, I occupy an intermediate race and class space — difficult to classify either with the assumed criminals or with the newcomers. As a journalist, I want to get beyond my personal outrage at being targeted and parse out the layers of the story. None of these approaches alone feels sufficient to me in searching for a solution, or brings me any closer to one.

At this stage, after gaining a greater understanding of the place I have newly come in to and where I witness efforts being made, in theory, to create safety, I’ve been thinking more critically about what that means. I’m wondering, whose safety is at the center and whose is expendable? I want to take into consideration that, while police might symbolize one thing for me, they mean something else entirely for others; that historically, working-class residents in this area and others like it around the country have not been kept safe by law enforcement. I have opened myself up to hearing their struggles as my neighbors, and I am working with my building’s tenants’ association to partner with groups like Equality for Flatbush. Simultaneously, I also acknowledge that I’m the stranger on this turf.

When we lost our things at the quivering hands of a young gunman and then later saw ourselves represented in the broad strokes painted by news reports, many of us in the group agreed that in some respects we identified more with our robber than with the characters we were portrayed to be. Still, when we quickly raised enough money to replace our devices through an online crowd-funding campaign, it was impossible to gloss over the immense capacity of our social capital.

I reflect on that a lot, as well as what Alicia said about what kind of power she possesses to fight the monster of gentrification. As I ask myself about my own power and begin to mobilize with other residents who are also at risk of being displaced, I know I have a responsibility to the community I now live in. And that is to use my position, however fraught, to stand up for and support my neighbors, especially those I recognize as silenced or ignored. As our pernicious policing practices endure, that’s the only way we can truly protect each other.