I need memory to be boundless, then. More infinite than.

May 1, 2023

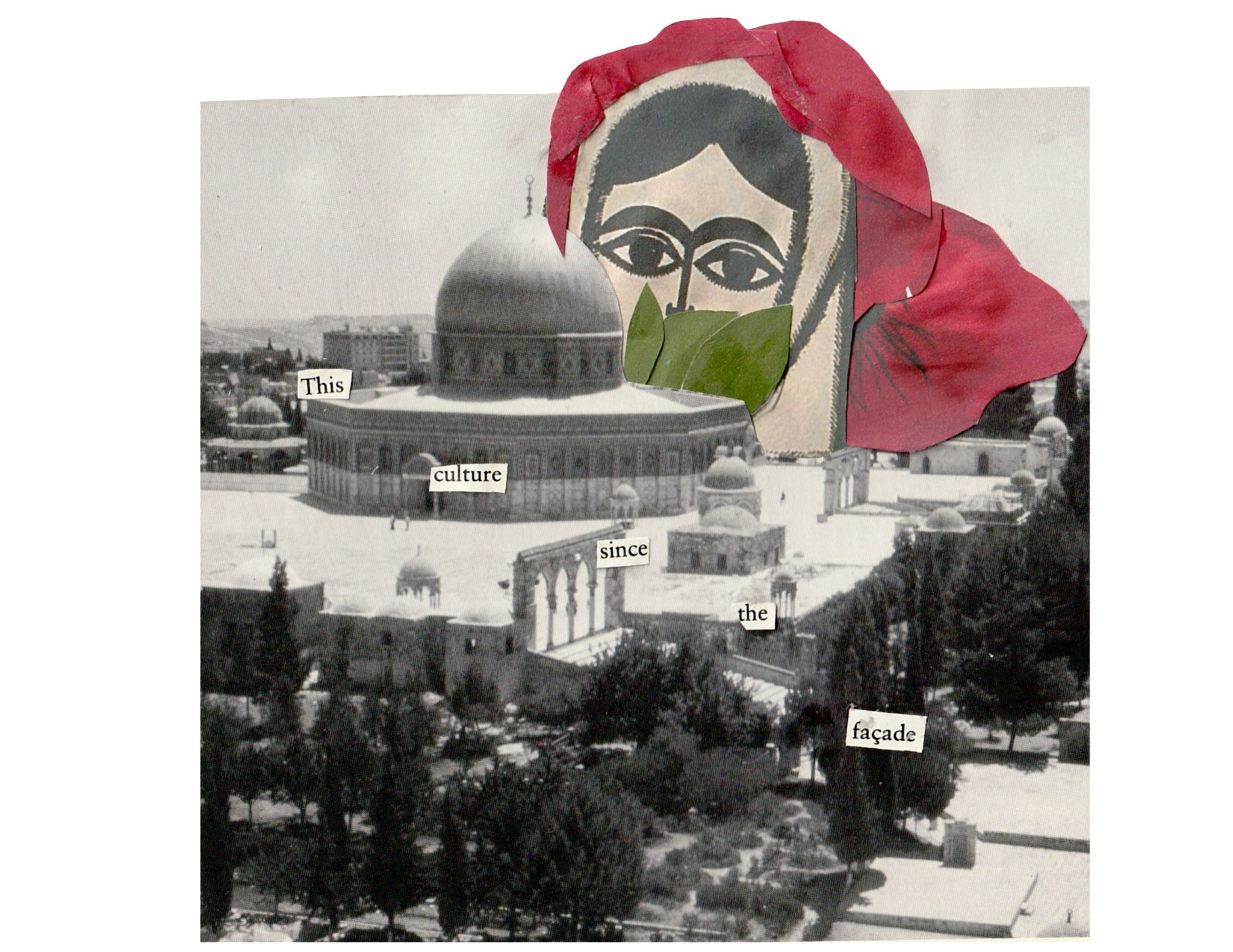

This piece is part of the Love Letters notebook, which features art by Ali El-Chaer.

Break and leave your husband for me.

There was a comma in that sentence, a period, maybe a with at some point too, but I seem to have misplaced them. Is it possible to misplace a husband like that?

There are hundreds of definitions for compactness—the most abstract involving open sets & finite covers, though most boil down to space that is both closed & bounded—though none are predicated on one’s proximity to singularities or other men.

I’m reading a novel about a Queer Palestinian with a clinical love addiction & I’ve never felt more Seen in american literature, though love (& american) here, of course, boil down to idea of, hence, the infinite folded into a single body, hence, a compactification.

Who am I kidding? said the man as he came inside me. I couldn’t see his face, so he didn’t have one.

Silly. No man ever cums in me, they only ever come

inside. The lines are broken even if you cannot see them that way, you’re welcome for

The first draft of this poem was titled “at the end of the world, I still / couldn’t tell you I love you.” Though I didn’t know who it was to, let alone For.

The poem, unlike me, unraveled in couplets, as you might have guessed.

At one point the you in the poem became a multitude. At another it became a self I didn’t recognize. Or deserve. Both were instances of running from.

I couldn’t trust the poem in my hands after that.

Before Marwa asked me, Are you in love, or is he just a distraction?

I’ve been thinking about how colonial it is to consider one’s fear of dying in a time like any time really. To write apocalyptic is to assume a certain immortality, a boundlessness.

There’s an image I’ve rewritten before, of that rough patch of bumpy skin hugging my tricep like a question mark—the one Marwa noticed at a wine bar once, lifting her sleeve to expose her own, saying these are the scars from when they stole our wings. Though I don’t think the image has found the right poem yet. The assumption, being. Angelic.

Shortly thereafter, we had the conversation that led to my first book’s title: Birthright.

Earlier that day, a man shouldered me into a bus window after glaring at my Palestinians for Black Power shirt. When I turned around, his shirt read Birthright.

Thereafter, I wanted to steal that & every word from him. Light them on fire. I confess, I wrote Birthright for people like him, if only for a single moment.

If you’re reading me, I want you to feel small, dare I say, compact.

Yes, I’ve considered my skin’s betrayal, a cloudlessness.

We can look into the sky & see technically infinite space, yet our memory of it is housed in countable cells. I consider many notions of imagination a kind of compactness in this way.

dult brains lose 1 neuron per second, I am told, by a man who wasted 95 million neurons of my time.

With each passing second, I am becoming less capable of remembering my own history, my own construction of self, & yet language, we are told, crystalizes. Consider language & memory as competing processes.

I don’t think my imagination is brave enough for the Poem in this. Don’t forgive me for that.

The first time I ever saw the word birthright was in an email announcing a “free trip to israel” for american high schoolers. I admit that fourteen-year-old me read the application, wondering how easily I could lie my self onto that trip. I didn’t understand the bounds, the closings, imposed on my Palestinian-ness then.

Or maybe I’m writing to reach that exact self, the exact limitless, who knew that to Return is to muscle memory.

I constantly fantasize about fictionalizing that memory into a story where a Palestinian boy sneaks onto a Birthright trip &, with his name, his un-accent, fools everyone, into thinking he Belongs there. Though maybe the real tension was the divergence of self.

The boy makes no friends in the story. The boy doesn’t fall into a grand israeli Palestinian love affair. In every version of the story, the boy leaves the trip after rediscovering his inhumanity in small talk over baba ghanouj, tasting it as less a failure in proportion than an absence of ash.

There was food & reiterations of Palestinian & jokes of under-seasoning in the story & there it became for who the story wasn’t For. In this way, it could have almost been mistaken for a Diaspora Poem.

Though, I wanted only to write the story for its closing images—the boy running, barefooted in the Mediterranean at dusk, whispering back to the waves: you wouldn’t believe how far I’ve come to tell you this. The two of them laughing like friends from a past life, before the police Lights’.

I’ve re-entered the same story again & again & every time, I romanticize the distance between: light & pigment, skin & sound, country & memory of.

I need memory to be boundless, then. More infinite than.

Don’t say border. Don’t metaphor.

I cannot unname the ocean here & it is almost as unforgiveable as a love letter I once wrote, ending:“isn’t living for your country just a slower way to die?”

Every day is a country I refuse, to die for.

Aren’t you tired of trying to fill? That void.

Some faggotries are always apocalyptic, even when what others know as world is not disappeared—somehow, a dance, a flight. Is always.

I wonder if, years from now, assuming we even get there, someone will look back & write about the use of bird metaphors to understand The Quote Unquote Flight Of The Palestinian People.

Omar says it is so human to leave & here I consider the opposite of faith, as anything but an absence of. Come

is the opposite of a promise, that I am always never someone’s

lover. Let me try this again: once there was a wilderness. In mapping, it became a closure. In nation, a bounding. In this way, every notion of country is a compactification of

self—I told you there was Breakage

here, even if you could not See it consider it a misplaced comma (period (image—

I’m trying to reach a you by the end of this, even if it leaves me bending backwards & kidding myself. once upon a time

there was the country you left & there was the country you could return to.

Say leave. Call it leaving. Consider the space between those found notions & collapse it into a single wingspan, the way every writing of history is an act of re(dis(possession)))).

Once upon a time, someone considered all of this a love story. The space between abandonments, a finite.

Let me try this again: some notion of world is ending. There’s a boy I can perceive only through glass & distance—& I cannot tell him what I can

not. I leave him unfinished as a country

I cannot abandon. The honesty is as underwhelming as it is compactifying.

Gaze into me or gays into me. The choice is

yours. I do not consider my self, a multitude, or husbanding grief.

There’s a poem that ends in its own speaker’s birth but I haven’t Found it yet. There’s a poem that swaps every notion of birth & marriage, & is okay living in the brief distraction of its body.

Over a thousand possibilities of self died with this poem. You’re welcome

To exit, wound. Consider the competing, processes. The cum &. Gone, just

leave. I want you

to leave me, and.

Leave me. Be.

This piece was originally published in Infinite Constellations: An Anthology of Identity, Culture, and Speculative Conjunctions (University of Alabama Press, March 2023), edited by Khadijah Queen and Kiini Ibura Salaam.