The dead decided to live upon us, demanding a second chance.

December 21, 2022

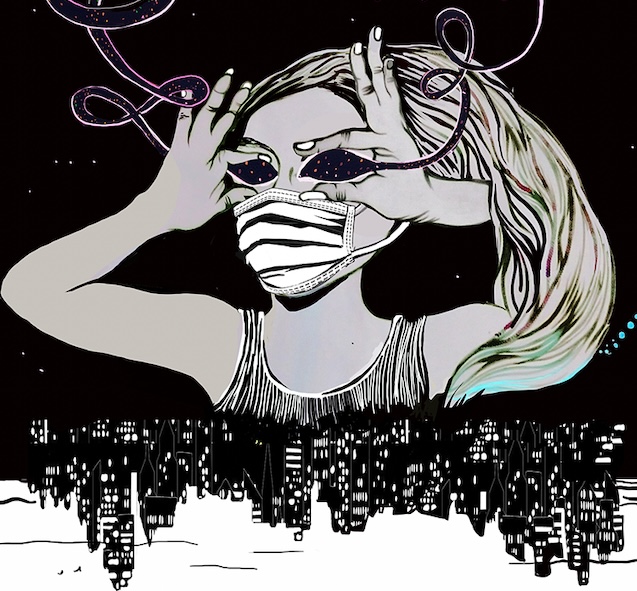

Not in Neem, our land,” they said. Then, they ordered us to bury our dead in the places where we came from. Never mind that our blood, sweat, and tears watered their desert land till it grew into the skyscrapers of Sheen City, the capital of Neem. They never told us why. The blight was killing us—but them? They had their towers and were safe inside, having closed their doors to us.

Then all the borders of the places we came from slammed the doors in our faces, afraid we would bring the blight packed in our suitcases or encased within the coffins. The bodies that died of the blight could not be sent back after decades chasing Neem’s broken promise to them. After the bodies started piling up, they let us bury them on the outskirts of the city, under mounds of the dry sand. Many decades ago, the ones in the towers set tents upon the sand as they welcomed us from the shores. We left the boats that brought us here in hopes of a new promised life in Sheen City. What fools we were. We made them their towers only to be cast out from them.

The next day, however, we would find the wrapped corpse back outside on the surface, six feet above where it was placed. The corpse was then placed back into its grave, only to pop back up onto the surface, as if to announce that it preferred to bake under the blistering sun than rot peacefully underground alongside the scorpions.

It is then that they told us the sands do not accept human bodies of any kind. Never mind the blood, sweat, and tears that the sand used from those same bodies when they were alive. The tale was that many years ago, a wounded woman who was brought to Neem to service men and bear children in exchange for gold cursed the land for her suffering before she died with her unborn child upon the sands, making it so that any human who resided in Neem would never find the comfort of death nor a way into the afterlife. The curse was one of Neem’s most well-kept secrets and until the blight took too many lives, tombs disguised as glass buildings in Sheen City were their loophole.

They then insisted we find a way to bury the bodies, but cars, boats, and planes can no longer leave nor come into the city. Eventually, because the desert was getting crowded with the stank of wrapped corpses, they forced cremation upon all the dead, regardless of religion or the protests of their next of kin. The protests were stifled when asked if the next of kin wanted to join their deceased on the massive pyre, the flames larger than the metropolitan fruit of their labor.

Soon there was a mountain of ash and nowhere to put it. Now, we ask, can we spread them in the sea so they may finally be free of Neem?

“In the sea would dirty the beaches, make them gray,” they say. “It won’t look good in the photos. Then the tourists won’t come once the borders open, and then we won’t get the money lost.”

But the money is no longer being made because those who helped make it are among the ashes. Our pockets have been empty for months.

So back into the desert part of Neem it was. We drove and drove with the pots of ash piled up on the back of trucks driven by us survivors and wondered if one of our friends were in the pots and whether that was a good enough answer to give their grieving wives and mothers calling again and again from outside Neem. The pots were opened and emptied out at different parts of the desert. They insisted the ash would mix in and become one with the desert. One could visit to pay respects or dune bash amid the dead. The tourists may even think the varying colors would look good in the vacation pictures. The tourists would spend their money again.

Instead of bodies, stories came to the surface—of how late-night campers found themselves waking up with ash in their nostrils and mouths, clogging the pipes of engines, trapping the wheels of vehicles and legs of people into a sooty quicksand. The ash would follow people into the metropolis, and no amount of soap or cleaning implement would remove it from the skin. Ash kept getting blown into the city and soon, everyone, from survivors on the ground and those in the towers, was covered in patches, and no amount of new paint on the buildings would cover it up. The dead decided to live upon us, demanding a second chance.

One day, the regular spring sandstorms began but instead of the sky becoming beige, it was all black and gray, as if a rainstorm would come. But those who had lived here long enough know there had been no rains since they mined the sea for water. Instead of sandstorms bringing in piles of the clean tar roads, the wind brought in piles of ash and soot that made people cough, sneeze, and go blind.

They insisted we were the ones making mountains out of any hills, till the ash clogged their throats into silence. The winds blew stronger. The ash became a whirling tornado, knocking down trees, windows, signs, cars, and soon even the skyscrapers of Sheen City, with the vengeance of souls mixed with shards of glass done wrong, till Neem was empty, and the ash was all that could be seen. After the borders were opened, those of us who remained left for the lands we came from. All that could be seen of Neem from the sky was a gray stain.

This story is part of the Remains notebook, which features art by Chitra Ganesh.