Karen Ishizuka’s ‘Serve the People’ tells the story of a radical period in Asian American activism, and compels us to ask, where does that lead us now?

November 17, 2016

The current state of crisis may feel oddly familiar and unfamiliar. We’re emerging from a political era when cosmopolitan worldviews seemed to be on the fore of everyone’s mind, yet the racial divisions laid bare by the election cycle show us just how divided the country has remained, throughout the post-civil-rights era. As activists begin to dust off old tools for grassroots mobilizing, hoping to kindle radicalism for an emerging political battlefront, the lessons of past generations of activists—who waged their battles in a much angrier, more brutal and more precarious political climate—haunt us today, but also give us perspective: we should never get too comfortable with what seems to be the status quo. For one movement born of migration, war, and cultural upheaval, history does move in cycles, and there’s always fresh disruption rising on the horizon.

Whatever chaos looms in our political sphere, if you just peer into our pop-cultural bubble, you might say Asian America is having a moment. AAPI faces and names festoon prime-time television lineups in leading roles, no longer typecast as bumbling foils or faithful sidekicks. The “Asian nerd” stereotype has acquired a certain geek chic cache, morphing into the millennial lifeblood of Silicon Valley’s nubile empire, and our trending feeds toggle between K-Pop idols and grandma’s soup dumplings as the next foodie craze. With or without the hyphen, today “Asian American” is an adjective that represents brand influence and social capital. So it’s hard to believe that 40 years ago the term represented nothing, not even to Asian Americans.

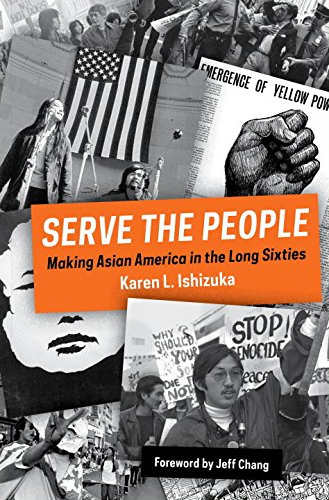

Karen Ishizuka’s Serve the People (Verso, 2016) peers behind the contemporary narrative of Asian Americans achieving “visibility,” with an intricate depiction of the movement that originated the Asian American vision, starting in the late 1960s and lasting through the late 1970s—the tail end of the “Long Civil Rights Movement.”

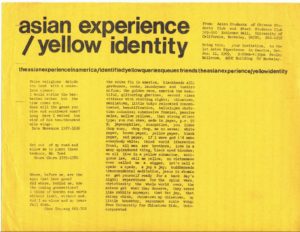

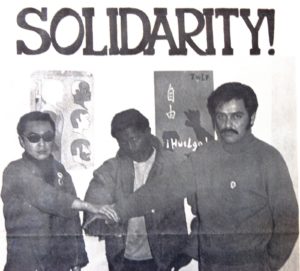

Asian American movement history has always been acutely self-aware; the movement itself revolved around the essential question of self-definition. The stories, interviews, propaganda, and print culture artifacts featured in Ishizuka’s history of the movement speak to a kind of rectification of names that Asian Americans underwent as they sought to carve out a place for themselves in the landscape of America’s civil rights struggles.

The book, which Ishizuka worked on as a side project while finishing lapsed doctoral studies, is one of the first comprehensive histories of the movement, but it reads more like a scrapbook: a mashup encapsulating both a moment of chaos and a sense of destiny. Excerpts of old pamphlets that fuse socialist realist and psychedelic imagery, mesh with Japanese brush painting and woodblock bricolage; archival photos of street demonstrations flash long-haired second-generation radicals rallying to defend their elders’ neighborhoods against displacement and discrimination. And even contemporary readers might be jarred by the scathing guerilla comics that turn epithets into satirical grenades. On a cover of the magazine Gidra, published in the early 1970s, a woman militant faces off against Asian American GI, as his white co-combatant eggs him on: “Kill that gook you gook!”

Ishizuka’s documentation of the movement shows how a collective of outsiders navigated a conscious struggle between gazing inward and reaching outward. Asian Americans came into consciousness when they began connecting the plights of different ethnic diasporas, linking discrimination “at home” with anticolonial and anti-militarism struggles abroad. The movement’s radicalism stemmed from its desire to define Asian Americans in terms of their dignity, rather than their marginality, as a people.

Reflecting on the Double Lens

Often it was the first encounter with the margins that made one truly conscious of one’s identity at all. Ishizuka tells the story of journalist Helen Zia, who grew up under a classic “Confucian patriarch,” an angry father who bristled at the racial segregation of her cookie-cutter American suburb, 1950s Levittown on Long Island. The bigotry was sometimes vicious—when their cookie-cutter house was pelted with eggs, for example—but often it simply hung in the atmosphere, an inevitable cloud that overshadowed her parents’ lifelong struggle to achieve middle-class status.

Zia’s reaction to a slur now feels like a vintage “Asian American experience.” She recalls: “That thing about ‘Where are you from?’ or ‘Go back to where you came from,’ I heard that so many times. Go back where? New Jersey? I’m here! They wanted me to go back to a place I never came from, so maybe I should be there.”

Rather than recoiling into conformity, Zia took her experience of alienation to a different side of the world and sought to “reconnect” with her ancestral homeland during a journey back to China in the early 1970s—then a common birthright mission of freshly radicalized Chinese American youth. But Zia grew disillusioned there, too. She then helped build movement that invented the in-between world inhabited by youth like her, who felt they were “genuine American chop suey.”

The evolution of Asian American activism revolved around a process of self-actualization. Ishizuka wrote in an email exchange I had with her: “We were not born Asian American but rather gave birth to ourselves as Asian Americans as a political identity to be seen and heard.” While many of the original radicals went on to flourish as community leaders or cultural insurgents in other offshoots of the Third World liberation movement, she also notes that in academic and commercial circles, “Now the terms ‘Asian American’ and ‘Asian Pacific Islander’ have been neutralized into a mere adjective.”

Her project, a pastiche of archive, memoir, and oral history—moves from a state of invisibility, into full-blown insurgency, and ends with a vibrant community that has achieved visibility by embedding itself into the very establishment it once revolted against.

Asians before Asian America

Before the Asian American movement emerged, Asians in the United States lived largely within insular cultural enclaves like the early Chinatowns, where merchants and laborers squeezed into crowded corners of New York, San Francisco, and other cities with burgeoning Asian migrant populations. These neighborhoods were products of legal exclusion and racial persecution, walled off from the outside yet strafed internally by ethnic divides and machine politics.

The Asian American movement was outward facing from the start, and in fact, for the previous century of American history, Ishizuka writes, “Asians in America were rendered politically disenfranchised and socially negligible.” And so the term “Asian American” was itself a generative concept, replacing an imposed identity with radical consciousness.

But stitching together such a cultural composite can be awkward, Ishizuka notes: “In addition to constraints of race and ethnicity, there are webs of class and gender, interethnic as well as intraethnic conflicts, generational differences, various immigrant states of understanding, situational realities, and infinite individual dispositions.” The ethos of pan-Asianism across the Third World spawned a fresh crop of radical second-generation Chinese Americans, Nisei, Filipinos, and others who bonded through rising race consciousness.

The movement staked its identity in large part on the revolutionary zeitgeist of the time. As Ishizuka explained in a recent conversation, war unified a motley crew of ethnic Others: “During the sixties we were very much affected by this imperialist racist war in Vietnam against people who looked like us that kind of pushed the question of: who are we? What are we?”

The romantic conceit of the worldwide insurgent struggle drove many to not only revel in, but to base their political identity on, opposing American imperialism. “Pushed by the Vietnam War abroad and racism at home, as well as pulled by the idea of Third World solidarity and the inspiration of the Black Liberation Movement—these were major dynamics that brought about our political identity as Asian Americans,” Ishizuka reflected.

In her view, “The rise of Black Liberation replaced the goals of equal rights and opportunity with those of self-determination and empowerment. Difference was now valued over sameness, and the broader climate of progressive opinion recognized a multitude of groups, such as ethnic minorities, women, and LGBTQ, emphasizing identity and subjectivity.”

This in part reflected the movement’s insecurity about its own identity, as well as a desire to define itself as an ally of other civil rights struggles. An early pamphlet, published in the summer of 1969 by a University of California Berkeley campus group called the Asian American Political Alliance, framed Asian American identity in terms of whom it was for and against:

We Asian Americans refuse to cooperate with the

White Racism in this society …

We Asian Americans support all oppressed peoples …

We Asian Americans oppose the imperialistic

policies being pursued by the American

government.

The manifesto went viral before there was a word for it. The idea of an Asian American movement ignited sister campaigns on other campuses. Previously, their ethnicity had rendered them neither here nor there in Anglo-American culture; now they stood on two sides of the world at once, aligned with a revolutionary vanguard wherever it erupted.

But by the time the movement began to flourish in myriad forms nationwide in the early 1970s, it was clear that the struggle had a home front as well. The terminology used to define the identity question broadened to encompass “Asian American Pacific Islanders.” This marked both a widening of the movement’s cultural scope and acknowledgment of imperialist relationships between the United States and these diasporas (for example, of the distinct history of Filipino “nationals” whose legal status was long defined through a territorial relationship). Eventually the effort for cultural affirmation and historical recovery branched out into other Third World solidarity campaigns, including symbolic Asian American delegations to Wounded Knee.

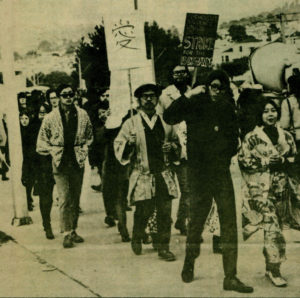

Other initiatives aimed to improve the material conditions of communities: social welfare networks formed, reflecting the same self-help ethos of the early Black Panther Party. Some labor activists threw themselves into mass organizing of garment factory workers, even creating a communal Chinatown garment factory in San Francisco, providing local workers with decent wages and working conditions as an alternative to “sweatshops.” Their militant protests against gentrification challenged the pattern of tokenizing and commercializing immigrant enclaves as static tourist attractions; Chinatown was not just a land of gambling dens and curio shops but a place where generations of families had lived and worked.

Yet for all their efforts to build a new politics of representation, they still embraced their old neighborhoods, however rumpled or dilapidated, as a historical touchstone, and a testament to cultural survival. “Even as Asian America was evolving,” Ishizuka writes, “its historic foundations were targeted for destruction, and activists rose up to save what was left.”

One iconic battle for public space, the struggle to protect famous I-Hotel of San Francisco, led to a clash between a human barricade of young community defenders and hundreds of riot police. Others evolved into campaigns to build more public housing, like Chinatown’s Confucius Plaza Project, and fueled broader movements to integrate grassroots community control into government-led urban development efforts.

Many of these initiatives would develop into decidedly less radical formations over the years, geared toward preserving the wealth and resources of Asian American communities, rather than fortifying them against white America.

Toward Visibility

Both in its rhetoric and its grassroots tactics, the branding of the movement’s activism was a conscious statement of pride. As Black Panther-turned-Asian American revolutionary Richard Aoki observed, “Up to that point, we had been called Orientals. Oriental was a rug that everyone steps on, so we ain’t no Orientals. We were Asian American.”

But by making the oppositional so central to its identity, perhaps Asian America lacked a sense of what it was, rather than what it was not. There was no language, religion, or cultural practice that unified everyone; just a generation of youth’s desire to somehow confront racial oppression on their own terms. Their practices shifted along with their politics, but continually revolved—perhaps more consciously than other youth-led movements—around the concept of building legitimacy and projecting identity through political activism.

And like the movement, Ishizuka’s history challenges its definition of itself from the beginning. She avoids lionizing leaders or sanitizing unseemly conflicts that eventually arose—ranging from ideological squabbles to tensions over gender divisions, to sheer power struggles between political personas within an organization or campaign. They were not unlike the internecine warfare that have dogged many movements on the left. On the other hand, the fact that Asian America was still in its infancy made it particularly fragile as a network of individuals. To parse this “spirit of collectivity,” Ishizuka highlights, through fragments of memory, individual activists to “remind ourselves of a kinship and mutuality that would otherwise remain unknown.”

There was the time radical New York artists Fay Chiang and Tomie Arai seemed to anticipate the post-1989 terminology wars in their “countless debates on the question of whether ‘Asian American’ should have a space or a dash.”

In one scene, women staffers of an antiwar newspaper in Boston lash out at male colleagues at a meeting, declaring themselves equal comrades, not “typists” as the men had obliviously labeled them: “You assholes aren’t listening to us and we’re changing the way this organization works right now. If you don’t like it you can leave.”

The ultimatum, to put up or get out, might bother an Asian American man who had grown up hearing such phrases from bigots, but in this context, veteran activist Steve Louie who was at the meeting actually had a humbling “light bulb” moment: “That incident crystallized a lot of things for me politically….The larger lesson was that you better include everybody in the room and you better figure out what your blinders are. At that time I realized I had blinders on, and I didn’t even know it.”

Grasping where one’s “blinders” are is the perennial turning point for activists, then and now, for individuals as well as whole movements. After the initial surge of political fervor—a maelstrom of antiwar agitprop, grassroots labor organizing, and anti-gentrification community advocacy that galvanized young Asian Americans’ revolutionary impulse—pioneers reach a threshold at which the quest becomes no longer solely to be visible, but to clear away ideological myopia, or to question the received wisdoms we have internalized about the movement’s basic agenda. Asian American activism, from the fair housing movements of the 1970s to the postmodern critiques of globalization today, has with each generation questioned its perceived power and its limitations: How do the myths of the “model minority” constrain us or burden us with singular responsibilities? Where does Asian America fit into, or rupture, the established racial taxonomy?

Here is where Ishizuka’s history interfaces with the current moment, when Asian Americans are more “seen” but not necessarily more heard in the public sphere. In an age when “identity politics” has become an epithet, and identity crisis is a state of being, we have an Asian America without a movement. Does it need one again? Ishizuka quotes filmmaker Spencer Nakasako expressing doubts about the “progress” of Asian America as it has shifted from a civil rights uprising to an academic field and marketing demographic.

Now there’s people of color everywhere, in all walks of life, even in high places, but is this a good thing? You have to ask, for what and for whose benefit? At UCLA, for example, there are dozens of Asian American organizations, but is this progress? They’re still doing the equivalent of Miss Chinatowns. Asian American Studies is now more professional and institutional than community-based. [So-called professional Asian Americanists] have become like who they replaced, and the irony is they relate better to today’s students than we do.

Did the movement’s professionalization doom Asian America to a political vacuum? Ishizuka is ambivalent, but overall, concludes that the movement she grew up in was a radical big bang that was meant to have a short half-life.

When I asked Ishizuka whether she believes the movement still exists in some form, she concluded, “The Asian America of the Long Sixties no longer exists—nor should it. Social movements are not meant to be continuing entities, because they must respond to the internal and external conditions of the times. My objective in writing the book was not to resurrect the [Asian American Movement] as it was then, but to know that it indeed existed in order to build upon it.”

Asian American activism has always hovered awkwardly between historical reverence and self-consciousness about the future, so Ishizuka appreciates the movement in its past present tense.

Their movement ultimately ran its course, ironically, because it had gotten ahead of Asian America itself. After the initial explosion of activism faded, the formation of Asian American identity grew more complex, grappling with questions of aesthetics and social status as well as political representation. In addition, Asian American studies, which had originated with Asian American radicalism, joined the academy in conventional terms, but, in Ishizuka’s view, became increasingly insular, separated from the community-based movements that had originally inspired it.

But the rising forces of assimilation and economic ambition meant that identity politics, tied to the aspirations and interests of increasingly diverse and prosperous second-generation bourgeoisie, ended up parting ways with the more militant political formations of that moment. Historically, too, the politicization of Asian American youth was something of an anomaly; low levels of civic engagement, in part tied to socioeconomic status, have muted Asian American representation even in the mainstream two-party political system.

By starting with Asian America’s “Big Bang”, Serve the People sheds a backlight on our hyphenated cultural present—not just in terms of who and what “Asian American” has come to mean, but also in terms of how any political movement becomes an identity and vice versa. We may never recapture the movement’s original sense of urgency, but we can see how the questions that propelled their actions still resonate today, and remain unanswered. The last page, which Ishizuka intentionally leaves blank, is where, sooner or later, the next generation of activists and storytellers will resume the work, and redefine it.

From Michelle Chen’s conversation with Karen Ishizuka for Asia Pacific Forum:

Michelle Chen: What was the essence of Asian American that made people feel like, “Hey, we should get under one label at this point in time?”

Karen Ishizuka: Until the late 1960s we thought of ourselves more as individual ethnic groups and we were under the assumption that if we could take care of our own then we could make our fortunes, but then we realized that was not happening and that we were not being heard, that we were considered foreigners in our own country and didn’t have a voice.

The construction was a response to having an identity imposed on us in some way, it was a way to reverse that. It’s a sense of shared oppression.

Also I think the Black Liberation Movement was very instrumental in pushing us to realize that we, too, are people of color, non-white in this country, and as such we do share a history of oppression.

How connected was the Asian American movement to international and transnational struggles?

Very much so. After decades of being orientalized, we were very much in tune with what was happening around the world and particularly in Asia, about Mao and Marcos, When we saw our fellow Asian countries being imperialistic to others, that was something in particular that we stood up against.

To the extent that Asian American history and politics are discussed, it is often a response to and critique of the model minority myth. It’s almost become a whole other trope to write against the model minority now. For most of my life I’ve been waiting to get over the model minority debate. How do you approach that in your own historical work? Do you feel like it’s a limiting framework, or do you feel like it needs to be grappled with in a more complex way?

It’s like the rerun of a bad movie. It’s very frustrating. I think we need to struggle with it head on. It is a fight and we have to be vigilant but at the same time there are so many other things as well. In the past we had such a kinship with the African American movement—there was more of a solidarity there than there is now. And that I think is very dismaying to people of my generation because third world identity and solidarity was an overreaching arc of who we were as Asian Americans.

In light of some of the recent organizing around Black Lives Matter, are there lessons we could take from the Asian American Movement to address how other communities of color wrestle with both anti-black violence and the pervasiveness of violence in society? I’m reminded of the debate around the Peter Liang case with the NYPD shooting a black man in a stairwell and that turning into this ugly identity politics debate that ended up leaving many people bitter. What lessons can we draw from the past?

A black nationalist back in the day once said that “Pigs come in all colors” and I think that we have found that to be so. We have conservative and anti progressives in our Asian communities and it gets back to that whole concept of Asian America not being an ethnic adjective but a political identity. It’s not so much alliance along ethnic lines as it is on issues. It’s that larger third world solidarity that could be useful now when people seem to think it’s just one on one, that the black fight is just a black fight, or the Asian fight is just as Asian fight, or that just because you’re Asian you have to side with Peter Liang instead of Akai Gurley. We need to look back and recognize and understand that it is a progressive context in which the struggle continues and not a racial or ethnic one. The more cross cultural, the more multicultural, the more third world we can remember that the larger struggle is a part of, the stronger each individual campaign can be because of that.

What do you think the relevance of Asian American studies is today?

Back when people were demanding ethnic studies, it was really to teach each other about our histories, to strengthen ourselves. Now there are so many PhDs and academic departments that have to toe the line and, by sleeping with the enemy, you almost become the enemy so to speak. There’s professional Asian Americans looking out for their tenure that have lost sight for the original reason for Asian American studies to begin with. Ethnic studies are important, but I would like to see it become a lot more community-oriented and go back to the concerns of Asian American political identity and empowerment. Not that the strategies have to go back to the 1960s—every era has to respond to the challenges and environment around it—but I would like to see Asian American studies become a lot more political and incorporate current issues like Black Lives Matter as much as the Chinese Exclusion Act. We need to get beyond an individualistic let’s get tenure and move on, let’s get a phD and join the academy.

As an activist what would you like to see the next chapter of Asian American history to be like?

In many ways young people are much more secure and confident than we ever were. They’re more comfortable in their yellow, brown skins than we were when we were taught that white is right. I think that we all know that assimilation is not the answer and that to strengthen ourselves is.