Reimagining the Malayan Emergency

September 6, 2023

This piece is part of “The Rainforest Speaks: Reimagining the Malayan Emergency,” featuring art by Sim Chi Yin.

Hunger was painless desire, impotent need mounting as the heat steam mounted and danced in the endless vistas of the rubber jungle . . .

Neo had never done anything wrong about his hunger and his thirst and that of his wife and children. Never had he taken sugar out, nor rice. And yet he was in a detention camp. ‘It is not fair,’ he thought, ‘it is not fair.’ But further his thought, benumbed, would not go.

—And the Rain My Drink, Han Suyin

How does one go where “thought, benumbed, would not go”? Han Suyin’s 1956 novel, And the Rain My Drink, stands as one of the few English-language accounts of the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960) not told from a colonial perspective. It describes Malaya at a time of war and transition, depicting the complex societal layers involved in a war between British colonial forces and communist fighters in the deepest reaches of the Malayan rainforest. This guerrilla war, however, is hardly a footnote in the present. Sometimes described as a “distant war,” it is relatively unknown as one of the founding wars of the Cold War in Asia.

Yet traces remain in the rainforest and the past is found within oral histories and narratives by those who lived through the war. Ever since the Emergency ended over sixty years ago, historians and documentarians, as well as writers and filmmakers, have painstakingly put together a history of the Malayan anti-colonial movement from fragments, arguing for a more complicated picture than the conventional narrative of British victory and imperial benevolence.

This notebook, “The Rainforest Speaks: Reimagining the Malayan Emergency,” continues that work with eight essays and stories. It gathers writers, translators, filmmakers, artists, historians, and critics across different languages and locations to represent this elusive past. Although each of the contributors is a generation or more removed from the events of the Emergency, they are driven to make sense of this history in the present—a history that often intersects with their own families. Filmmaker Lau Kek Huat and artist Sim Chi Yin, two contributors featured in this notebook, have documented the Emergency in previous works through searches for traces of their grandfathers—both involved in anti-colonial activism during the Emergency—a fact that links both, even though they are now based in Taiwan and the United States, respectively. Translator and writer Jeremy Tiang also traces his interest in this period back to his relatives’ home—a New Village the British created during the Emergency—that connects him back to Malaya, even though he was born in present-day Singapore.

These pieces follow previous writing about the Emergency that can be found across different languages—English, Chinese, Malay, among others—but are rarely discussed in relation with one another. While the main languages in “The Rainforest Speaks” are English and Chinese, the hope is that future work can take on this fragmentation, to further supplement our understanding of the Emergency.

Nicholas Y.H. Wong’s critical essay provides a starting point for thinking about the linguistic and generational gaps that contribute to this fragmentation. Linking disparate literary works that narrate the Emergency across languages and groups (Sinophone, Anglophone, and Indigenous), as well as ideologies, he argues that what is truly interesting about these prior attempts, be they restitutive or rehabilitating works, is their inhabiting other points of view. Jeremy Tiang’s essay describes his efforts to translate Hai Fan into English, and deals with similar themes of comprehending unfamiliar points of view—in this case, that of a guerrilla fighter who entered the rainforest to join the communist struggle. Sharmini Aphrodite’s short story narrates the Emergency from the point of view of an Indian plantation worker—oft-neglected in conventional narratives of the Emergency that focus on its impact on Chinese, Malay, and European communities. And in a cross-continental and linguistic collaboration, YZ Chin translates Taiwan-based Malaysian writer Teng Kuan Kiat’s short story about an abandoned funfair in Malaysia, symbolizing the ghostly resonances of history in the present.

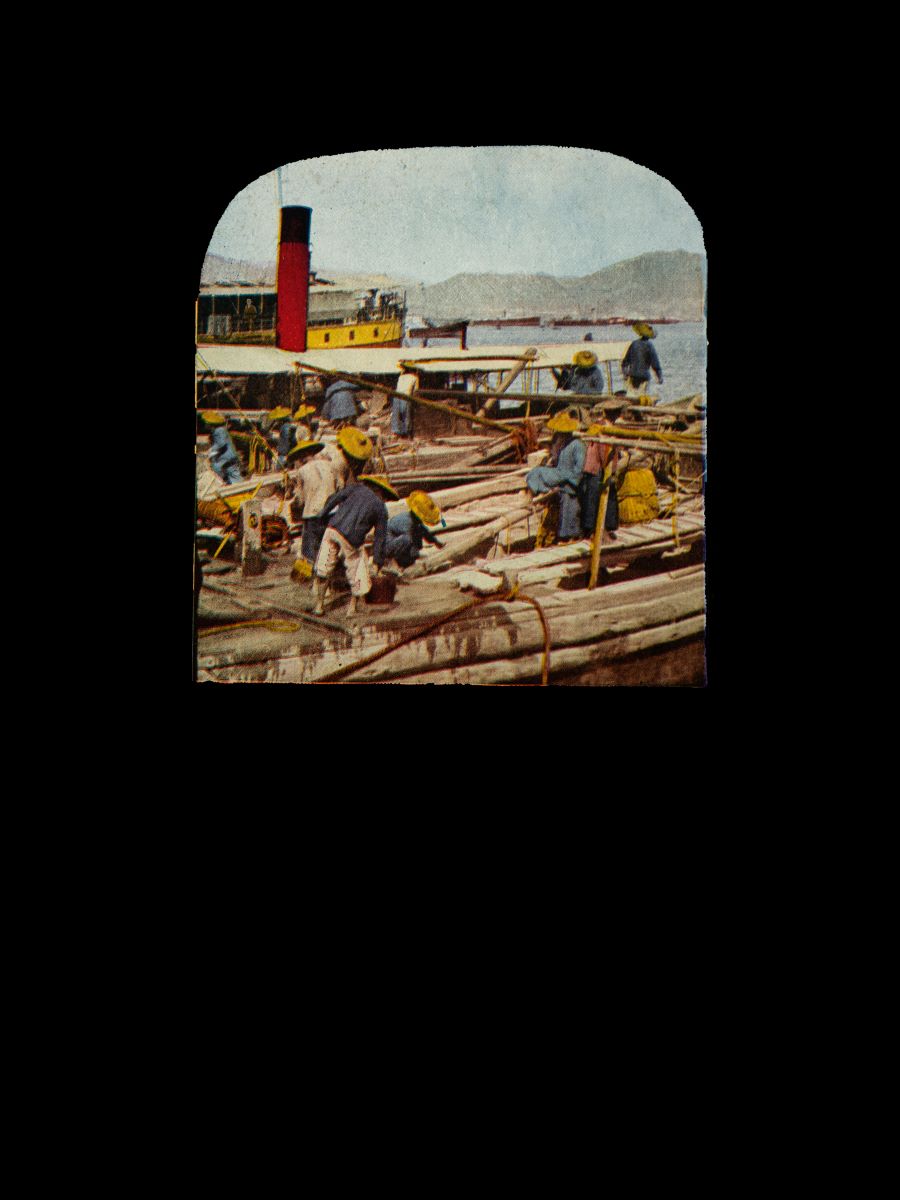

Nadine Chan and Lau Kek Huat’s pieces both deal with colonial images of the Emergency and the importance of reframing their archival power—the former showing its impact on the very way we speak of the tropical environment, the “jungle” a term that frames how Southeast Asia and the Cold War is visualized through military conquest, leaving conceptual sediments of “imperial warfare” upon the Malayan rainforest. Likewise, filmmaker Lau Kek Huat’s notes on his 2016 documentary, Absent Without Leave (不即不離), translated by Leong Jie Yu, points out the difficulty of visual representation for filmmakers, when even control of and access to the archive is a fraught issue, due to the vestiges of state and colonial power. ZH Liew’s essay remembers a trip to the UK National Archives and the contradictions inherent in finding past lived reality in colonial documents, when this reality is the same one that the colonizers have been erasing. Breaking from the archives, Fiona Lee’s essay on three recent Southeast Asian artworks draws a throughline from the Emergency to the present-day emergencies of COVID–19 and the climate crisis, and intervenes to surface other ways of relating to the environment and one another, beyond state-imposed emergency logics.

The urge to return to scenes of the Emergency, to look beyond the colonial archive, is not only a painstaking task of recording imperial wrongs that persist in the present. It is, above all, an imaginative task, one that cannot be captured by one individual or group. Sim Chi Yin’s photography, which challenge Cold War orthodoxies in Southeast Asia—the “gaps, aphasia, and specters around decolonization wars in the Global South,” as she puts it—thus aid us in reimagining both the spaces and archives of the Emergency. Her imaginative work accompanies the pieces in “The Rainforest Speaks.”

While editing this notebook, we found ourselves struck by our own ignorance of the whole, vast history of the Emergency and the many tremors it sends into the present, yet we were also strangely drawn in by the various visions of the past presented in the works found here. As Faris Joraimi notes in his essay on Sim’s art: “This may be the counter-method to history as a study of the past from an omniscient vantage point: to be pulled in inexorably by a past, following where it leads, through memory and silence.”

If nothing else, “The Rainforest Speaks: Reimagining the Malayan Emergency” stands as an attempt to do so—to follow where traces of the Emergency may lead, be it in the past, present, or future.