Malaya’s rainforest in the colonial and military imaginary

September 6, 2023

This piece is part of “The Rainforest Speaks: Reimagining the Malayan Emergency,” featuring art by Sim Chi Yin.

The 1961 military instructional film Keeping the Peace: Part 1 begins with a slow right-to-left pan over a vast canopy of trees spreading out as far as the eye can see. This bird’s-eye view depicts thick tropical rainforest as how it would have appeared from the air and at a distance: impenetrable to sight, occluding to knowledge, and entangled and folded in upon itself in a complex and confusing labyrinth. Shot through a colonial and military perspective, the film shows what the Malayan forest presumably looked like in the European imaginary—a hostile and unforgiving landscape. The film’s British-accented narrator then introduces the tropical forest as a lawless place where communist “rebels, guerrillas, terrorists, bandits” hide out alongside “wild animals” and “primitive people” in defiance of constitutional law and order. Hiding armed resistance fighters, surreptitious intelligence networks, and dangerous political ideologies that had to be rooted out, the Malaya peninsula’s central rainforest is described by Keeping the Peace as a deeply militarized zone that had to be dealt with through precise military training, strategies, and tactics.

As a war that straddled Malayan independence from British rule in 1957, the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960) shaped the way tropical forests would be configured and imagined after independence and into early forms of postcolonial statecraft. As Maureen Sioh argues, the violence and suspicion with which the rainforest was viewed molded cultural attitudes towards deforestation carried out in postcolonial Malaysia.1Maureen Sioh, “Authorizing the Malaysian Rainforest: Configuring Space, Contesting Claims and Conquering Imaginaries,” Ecumene, April 1998, Vol. 5, No. 2 (April 1998): 159-161. The military’s treatment of the forest as unruly and undesirable terrain in need of removal or ordering precipitated, for example, state-held beliefs that the rainforest was “unused” land at best and dangerous terrain at worst—attitudes that facilitated the vast amount of deforestation for industrial, agricultural, and other economically extractive purposes. Malaya’s forested counterinsurgency war, furthermore, prefigured other forested military Cold War campaigns in Southeast Asia. For instance, various aspects of US counterinsurgent warfare in Vietnam were tried and tested in colonial British Malaya. The cultural imagery of the Vietnam War, as presented by the United States, are images of tropical forests that are hostile militarized spaces, something to be cut back, infiltrated, bombed, burned, and poisoned. These imageries of militarized forests had their predecessors in the discursive practices surrounding the Malayan Emergency, particularly in the propaganda and educational films made by the Malayan Film Unit (MFU) from the late 1940s and into the early 1960s, such as Keeping the Peace. A government-sponsored filmmaking agency, the MFU made hundreds of propaganda, instructional, and military films during the Malayan Emergency and beyond. Widely screened and seen by the public, the MFU’s Emergency-era films shaped decades of cultural animosity toward the tropical forest as sites of military violence.

Keeping the Peace, a three-part series of army instructional films on counterinsurgency operations, was made between 1959 and 1961. The films were sponsored by the War Office in Great Britain, with the third part also produced by the Malayan Film Unit. Keeping the Peace: Part 1 (1959) details counter-communist insurgency operations on a fictional tropical island called “Sembaga,” while Keeping the Peace: Part 2 (1960) covers counter-terrorist operations in an “unidentified north-west European country.” While fictitious, “Sembaga” may be read as a stand-in for either Singapore or Penang, given how both “tropical island[s]” harbored influential presses and would come under strict security measures during the Emergency. It is possible that the three films would have been screened to NATO forces engaging in combat (or preparing to do so) as the way the British handled Malaya’s so-called “jungle-based insurgencies” became a model for subsequent global counterinsurgencies during the Cold War era.2Nancy Lee Peluso and Peter Vandergeest, “Political Ecologies of War and Forests: Counterinsurgencies and the Making of National Natures,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101, no. 3 (2011): 592. By calling Malayan forests “jungle”—itself a discursive naming practice intended to signify the removal of the forest from civilization and society—Keeping the Peace visualized the forest as a space in need of surveillance, reformation, containment, and removal at the behest of imperial states. As Nancy Lee Peluso and Peter Vandergeest put it, “Jungles are associated with insurgency and thus became violent versions of political forests.”3Nancy Lee Peluso and Peter Vandergeest, “Political Ecologies of War and Forests: Counterinsurgencies and the Making of National Natures,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101, no. 3 (2011): 588.

How did tropical forests become viewed as militarized terrain? And what was it about Southeast Asia’s tropical rainforests that called for particular forms of military strategy? As a film made to train infantry soldiers to conduct tactical guerrilla warfare in densely foliaged and undulating terrain, Keeping the Peace offers insight into how the military approached the forest as a kind of environmental hermeneutics—a way of thinking, seeing, and sensing that was shaped by the environment itself. Every material and sensory aspect of the tropical forest—its flora and fauna, its topographies, its humidity, and its sonic and ocular temperaments—became subjects of military strategy.4Pujita Guha and Abhijan Toto of the Forest Curriculum, for example, describe how the forested and mountainous terrain of the Central Highlands of Vietnam confounded visualities and disrupted wireless communications, compelling the US army to develop new, signal-based and networked radio technologies. Pujita Guha and Abhijan Toto, “Media Ghostings: Three and a Half Hauntings of the Vietnam War,” ACT 77, April 2019. http://act.tnnua.edu.tw/?p=7320. Accessed Sep 3, 2023. These environmental features defined troop action and deployment in highly specific ways.5Nancy Lee Peluso and Peter Vandergeest, “Political Ecologies of War and Forests: Counterinsurgencies and the Making of National Natures,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101, no. 3 (2011): 592. For instance, forested environments, with their obscuring canopies and dense foliage, called for a kind of guerrilla warfare and military subterfuge as opposed to the “battlefronts” and heavy artillery of more open terrain. As a result of the highly variable terrain in the rainforest, troops were taught to wind their way single file through lianas and tall grasses seeking out hidden enemy camps, or to lie in ambush, shrouded by vegetation. As opposed to a single linear timeline, such variability in “military strategy” is depicted in the film as multiple temporal possibilities through numerous drills and reenactments of possible battle scenarios. As I further discuss later in the essay, this array of filmic temporal possibility takes on a level of formal contingency in the film that reveals state attempts to rationalize and contain the forest as an unbounded and unruly place. Forests, or the “jungle” in colonial terminology, were imaginative and discursive hermeneutics with concepts of entanglement, complexity, contingency, and unruliness that influenced many areas of British counterinsurgent military and colonial thinking.

The colonial imagination historically configured the tropical forest as a place filled with perilous inhabitants and deadly diseases.6On the context of Spanish colonizers in the Philippines see Anderson, Warwick. Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines, Durham: Duke University Press, 2006: 76-77. See also, David Arnold, The Problem of Nature: Environment, Culture and European Expansion (Oxford:Blackwell, 1996); Felix Driver and Brenda S. A. Yeoh, “Constructing the Tropics: Introduction,” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 21, no. 1 (2000): 1–5; Nancy Leys Stepan, Picturing Tropical Nature (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001); and Felix Driver and Luciana Martins, Tropical Visions in an Age of Empire (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005). The specifics of the Malayan Emergency expanded this imagination. Now harboring what the colonial government frequently (and unjustly) called “communist terrorists,” Malaya’s forests took on terrifying political proportions. In order to disrupt the guerrilla operations, which were carried out from the hilly forested terrain that stretched down the length of the Malayan peninsula, the British colonial government in Malaya rearranged, removed, repossessed, and militarized the forest. They built “jungle” forts (in reality, secluded British military bases built in the deep forest), resettled civilians away from the forest fringes and into guarded compounds (the infamous New Village policy), and conducted armed raids into Communist guerrilla camps located deep in the forest.

This militarization of the forest was accompanied by numerous propaganda films that represented the space as hostile and in need of infiltration and removal. Such figurations recur in the numerous propaganda films of the Malayan Emergency. Like Keeping the Peace, both Jungle Fort (1953) and A New Life: Squatter Resettlement (1951), begin with aerial views of the forest with shielding canopies described as harboring enemy presences, real and imagined. These films, along with others made by the Malayan Film Unit in the early 1950s, were screened to audiences such as resettled civilians and military personnel in order to push the anti-communist agenda and to prepare the population for the kind of forested counterinsurgency war that the Emergency was shaping out to be. Many civilians faced resettlement into state-planned neighborhoods, which meant a complete change in their living situations and often livelihoods from forest-proximate areas to more (sub)urbanized settings.

Made in 1961, a year after the first Malayan Emergency had been officially declared as “over” and only a few years into Malaysia’s new independence, Keeping the Peace is a curious artifact of this transitional period. Unlike other earlier Emergency films made by the Malayan Film Unit, which were targeted at resettled villagers and other civilians in Malaya, Keeping the Peace was directly addressed to the army recruit—a foot soldier presumably about to face combat in a Malayan tropical forest. The film not only sets out to train the soldier in various drills important in “jungle” warfare, but also to introduce the material conditions of the tropical forest itself. This suggests that its intended viewer was likely unfamiliar with living or fighting in the tropics. The lack of any appeal to nationalist sentiment or rhetoric about independence—a familiar clarion call in other MFU films of the time—implies that the intended audience was not, or at least not limited to, Malayans.

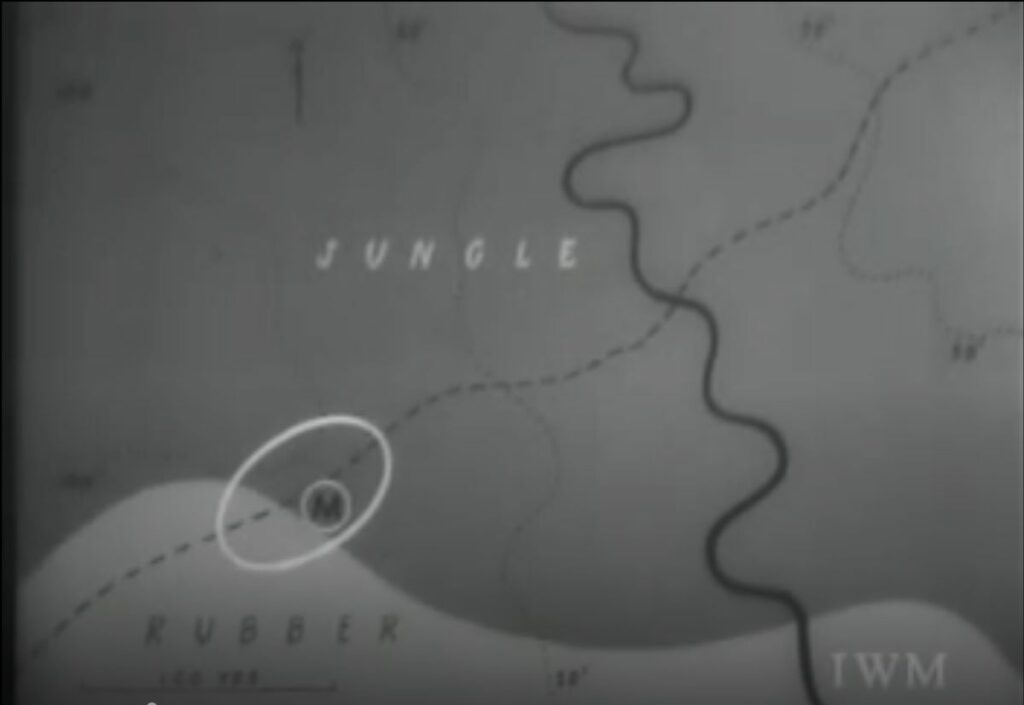

What, or where, exactly is the “forest”? While tropical forest appears to occupy a fixed zone in the warm and humid zones around the equator, in reality, the “forest” exceeds any physical place. As we see in Keeping the Peace, the spatiality of the forest was conceptualized in competing and conflicting ways. On the one hand, Keeping the Peace features multiple scenes that represent clear delineations between forest, forest-bordering habitations such as rubber plantations and small settlements, and urban towns. According to the film, Malaya’s guerrilla organizations were spatially organized: the fighting arm lived in small and mobile platoon-sized groups “who could be moved from place to place” in the forest, civilian supporters of the Communists lived in the towns, whereas the political groups that controlled the fighting forces operated from “jungle hideouts in the fringes of habitation”—visually represented through a long shot of a sharply defined tree line where the vegetation was clearly cut back. In another scene, an illustrated map clearly separates the boundary between natural forest and plantation. Strategically, military personnel are advised to walk in single file, evenly spaced when patrolling thick jungle, but are ordered to fan out when patrolling rubber plantations where even spacing and cleared undergrowth allow for excellent visibility.

On the other hand, the film also describes the forest as having blurred and porous boundaries. In spite of military attempts to organize the forest (such as through topographical maps and strategic action drills), the jungle “leaked” undesirable elements into surrounding areas. For example, several scenes show resistance fighters sneaking out of the foliage and into towns and villages, and then just as easily melting back into the shrubbery like ghosts when they come under fire. As the narrator describes, kinship ties between the Communist fighters and the civilians who live outside the forest fringes made allegiances across foliaged and non-foliaged areas impossible to amputate. The film’s narrator states, “It is well nigh impossible to deny these terrorists contact with the populations of towns and villages as most of them are implicated through blood ties or forced to collaborate through fear.”

The forest took on an amorphous presence where its complexity and material density stood in for the ties between fighters and civilians, guerrillas and their willing (and unwilling) collaborators that were a challenge for the state to contain—ties made through blood, ideology, trade, and kinship networks that exceeded state-sanctioned relationalities. Aside from the kinship networks between the fighters and their civilian families and friends who were often Malayan Chinese, other forested networks included collaboration with members of the indigenous Orang Asli tribes who were compelled to serve as spies, trackers, guides, couriers, and food providers for the Malayan Communist Party guerrillas. The latter connections were formed through decades of trade and marriage, and especially through threats of violence that materialized as mass shootings and slaughter should the tribespeople refuse to aid the guerrillas. Thus, the forest was full of labyrinthine subterfuge and tentacular networks that were impossible for the government to fully uproot.

These complex, and at times, contradictory ideas around containment and unboundedness, associated with the tropical rainforest, informed many areas of Emergency-era military logics. Keeping the Peace describes the forest as something that had to be kept at bay. This was most evident in how the military presented the boundary between the fighting body (historically envisioned as abled, male, and European, and therefore not adapted to tropical conditions) and its environment. Through special equipment and gear, the “jungle” was kept at bay through mosquito repellent, pants that tucked into boots (to keep the leeches out), a machete to hack at tangling lianas, and powder for foot rot. These devices helped to keep the imperial body impermeable to the forest. And yet, the well-trained foot soldier was also expected to learn how to make his body become as one with the “jungle”— to melt into the brush at the sign of an approaching enemy, to blend in with the trees and sit and wait silently for hours, and to leave as little impact on surrounding flora and fauna as possible. Mimicking forested hermeneutics of porosity and camouflage, combat in the tropical forest called for tactics that helped troops physically “disappear” into their environment.

Such an imaginary of the forest as both porous and passaged extends to a militarized understanding of the physical makeup (or “architecture”) of the interior forest. This is aesthetically represented in the many scenes in Keeping the Peace depicting reenactments of foot patrols that take place in deep forest—that is, close-up shots amongst the foliage. In contrast, the shots of the forest from the outside or from above are filmed at a great physical and aesthetic remove from the space (such as with the aerial opening scenes).

As aesthetics of concealment and porosity; the forest as a lobed labyrinth through which the camera weaves.

In these forest interior scenes, soldiers, along with the camera, either weave through footpaths and gaps in the undergrowth or lie in wait, concealed behind the foliage. When viewed close-up, the forest is no longer always a space impenetrable to sight, but a folded and lobed labyrinth full of passages and pathways, hidden lairs and coves, foliage that could obscure or reveal. It offers moments of opportunity or restraint, visibility or concealment. The camera itself alternates between an aesthetics of porosity (tracking a patrol as they weave through gaps in the trees, revealing an ambush through a break in the branches) and an aesthetics of concealment (letting a soldier become hidden behind a large palm frond, having a platoon scattering into thick brush vanish from sight). These alternating cinematic aesthetics, which combine concealment and visibility, represent a militaristic view of the forest as a fickle space that is both impervious and permeable at the same time—a space particularly suitable for ambush, subterfuge, and scattered violence rather than the clear visibility and outright surveillance of frontline warfare. “The jungle is neutral,” the film’s narrator states, “but the foe can be very cunning.”7Here the narrator likely references British soldier Spencer Chapman’s 1950 book, The Jungle Is Neutral, which details his three and a half years in the Malayan jungle during World War II. Spencer Chapman, The Jungle Is Neutral, London: Chatto & Windus, 1950.

As an environment both porous and impervious, the forest made it very difficult to predict the exact route one’s enemy might take. Would they follow the edge of the rubber? Follow the curve of the land through deep forest? Saunter down the various tracking trails? Military strategy was dependent on being closely attuned to forested topographies, the intersections of streams, the curve of the land, the density of foliage. But even the most carefully planned ambush was subject to terrifying chance due to the folded and ever-shifting nature of the foliage and the landscape. Because of this fickleness, to the military mind, the rainforest was prone to the unexpected. Much of Keeping the Peace is devoted toward military drills and strategies—picturing the various routes that the enemy might take to approach a particular location, and what to do if an ambush doesn’t turn out as planned. These drill scenes—which take the form of multiple detailed reenactments complete with full-on gunfights—are a form of contingency management intended to mitigate the perceived mutability and unboundedness of the rainforest.

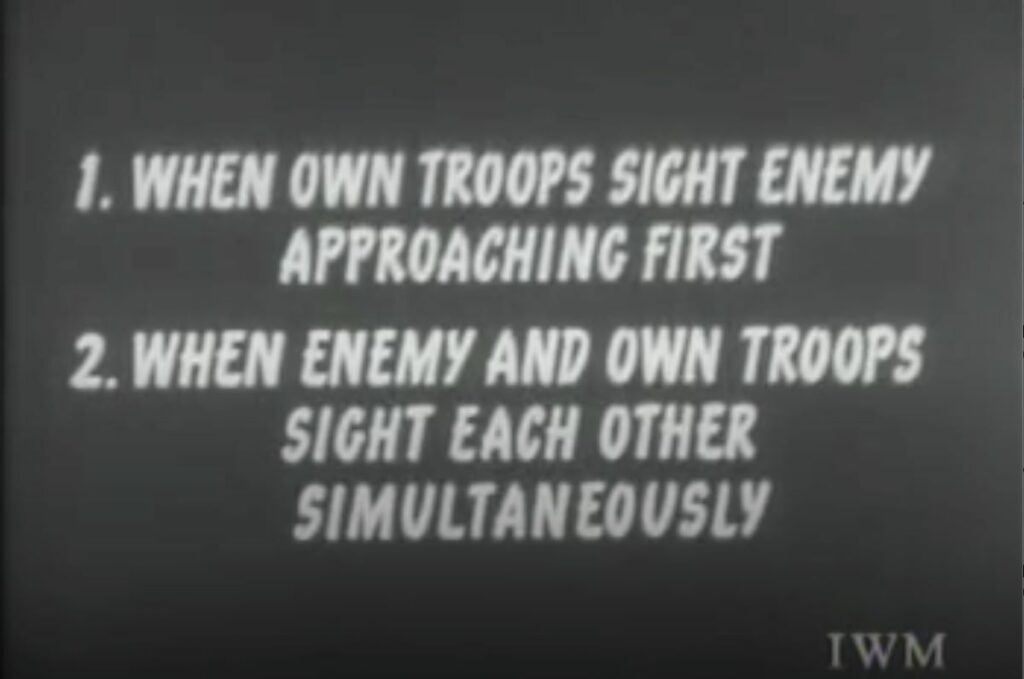

Reenactments for each of the above possibilities are played in turn, resulting in a film with multiple, contingent temporalities.

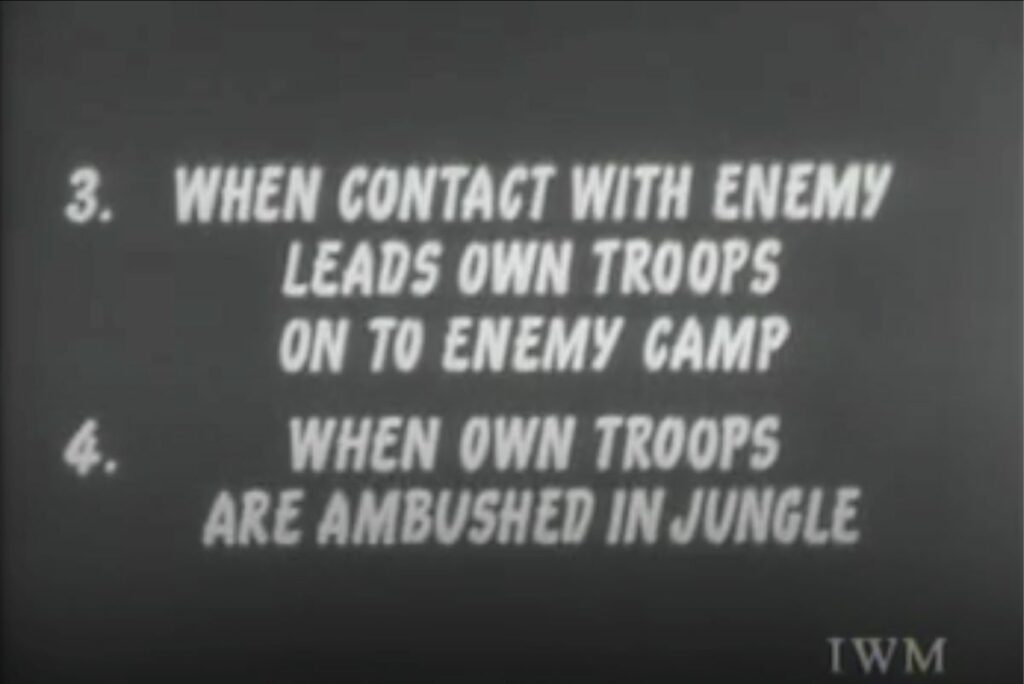

Formally, the training film does not follow a linear narrative but depicts several timelines through these varied reenactments. Some of these timelines cover what to do: “1. When own troops sight enemy approaching first,” “2. When enemy and own troops sight each other simultaneously,” “3. When contact with enemy leads own troops on to enemy camp,” and “4. When own troops are ambushed in jungle.” Unlike a typical film with a single timeline, Keeping the Peace adopts multiple timelines that branch out of the many unpredictable forms that a single violent encounter might produce in the forest. The number of possible outcomes, and the very specific actions expected of the soldiers if any of these were to occur, are dizzying and exhaustively covered in the training film. This nonlinear, contingency-driven temporality of Keeping the Peace illustrates the military’s perception of the forest as an environment riddled with risk where hard-to-predict outcomes had to be duly managed though meticulous planning and exhaustive training.

In the film’s closing scene, the forest is bombarded by the airforce and heavy artillery. According to the narrator, guerrilla fighters flee into even deeper “jungle,” leading command ops to decide that the best way to root them out is to ambush all known escape routes and “mount an air and artillery strike in the area.” The webbed interiors of the forest give way to shots of bombs being dropped from aircraft over the obscuring canopy, and of heavy artillery being fired from wide clearings into walls of “jungle.” The narrator declares, “The airforce and artillery . . . can reach out quickly over vast and impenetrable jungle and strike the terrorists immediately in areas that would take the infantry some time to reach.” The discourse of rationalization over the tropical topography ultimately escalates into blanketing violence from the air and subjugation via the sheer power of armament, but even so, the complexity and obfuscation of forested environments prevent clear and targeted strikes. Instead, “bombardment by day and night” works by tiring out the fighting forces, compelling them to flee and run into ground troops or to give up and surrender. In the labyrinthine forest where canopies and vegetal contours obscure the land and its inhabitants from aerial targeting, air strikes are only of secondary importance to the primary role of ground troops. As the narrator declares to the viewer, “But whether it is waiting for them to come out, or engaging them in their hideouts, in this kind of warfare, it is the infantry man who sets the tune. On him, on you, depends the outcome of the fight.”

Artillery and air strikes bombard the forest from its edges and from above.

Bombed from the air, bombarded from its edges, and infiltrated by foot, the rainforest becomes co-opted into acts of war and concepts of imperial warfare. Made at a critical juncture in the Southeast Asian Cold War—in the twilight of the first Malayan Emergency and right before US military escalation into large-scale ground and air combat in Vietnam—Keeping the Peace is an eye into how Malaya’s tropical rainforest became visualized as and through a hermeneutics of violence. Images like these would become iconographic of Southeast Asia’s experience of the Cold War in the decades to come.

All images are screenshots from Keeping the Peace (1959–1961).