但巡迴遊樂園並不害怕,只要再次拆卸自毀,它們換個地方就可以重新活過來。

| As long as the traveling carnival committed self-destruction, it could come alive once more in a different place.

September 6, 2023

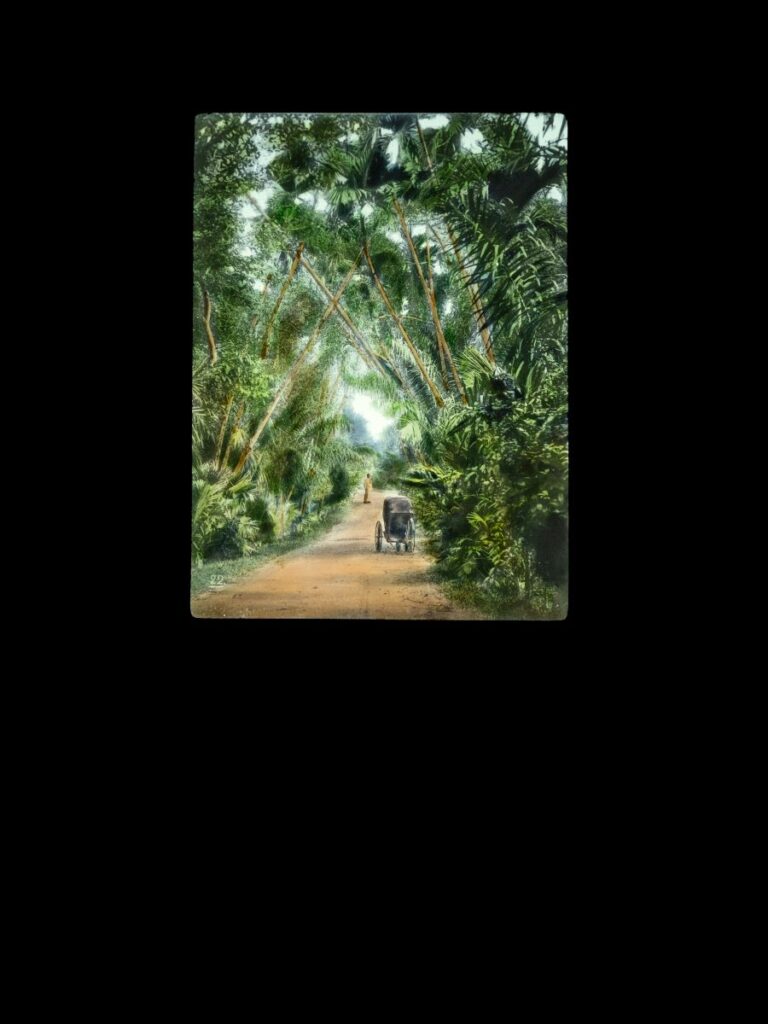

This piece is part of “The Rainforest Speaks: Reimagining the Malayan Emergency,” featuring art by Sim Chi Yin.

樂園

事情應該要從頭說起,但關於故事的開頭建國所知不多。父親失踪之後,原來他以為自己知道的事也靜悄悄地滑流鬆動。像那些無良發展商蓋在沙質土壤上的房子,人們在裡面吃飯、做愛、洗廁所,多年以來日子相安無事。某一天他們如常回家,發現房子似乎有哪裡不一樣了。他們不安地上下敲打傾聽,感應到牆壁內飽飽地裝滿尚未綻開的裂痕,但他們找不到問題的來源。夜晚他們惴惴入眠,連打小孩都不敢用力。

等到第一朵裂痕露出牆面,房子四肢癱軟,他們發現事情已經來不及了。

建國多年的經驗告訴他,要解決問題必須要從頭開始。

而且要快,不然就來不及了。

第一件可以確定的事:建國從小就沒有母親。但一個母親的消失,可以有很多方式。究竟是病死了?跟別的男人跑了?難道是難產?每次問起,建國父親臉色鐵青,抿著薄薄的雙唇不說話。建國的父親總是沉默寡言,尤其不喜歡提起過去的生活。不過建國認為這也是情有可原的,畢竟他帶著一個拖油瓶當了一輩子鰥夫,換作是建國,他也會對世界感到疲憊。

(是因為這樣才悄悄失踪的嗎?)

父親的家鄉在哪裡?關於這件事,建國也只能用猜的。聽父親的的口音,他家鄉應該在馬來半島北部。不過到建國稍微懂事的時候,他們家在半島最南端的柔佛州。父親身體孱弱,還帶著一個小孩,只能四處遊走打些輕鬆的零工,根本賺不了多少錢。建國對不斷搬家的事記憶猶新,搬家的時間多半是在晚上,小建國在睡夢中被喚醒,發現自己的東西都裝在行李箱裡,他就知道要搬家了。當然,大部分時候是被房東趕走的,但即使遇到好心收留他們的房東,父親住沒多久也會悄悄帶著建國離開。

他們一路向著南方遷徙,有時幾天就會換一個地方,簡直像在逃難一樣。

現在建國想起來,當時大概真是在逃難吧。

(那現在呢?戰爭不是早就結束了嗎?)

遊樂園就是在搬家的路上出現的。話說那天建國的父親再次被房東趕出門,小建國問父親要去哪裡,父親沒有說話。夜色已經很深了,兩個人帶著一個大行李箱,站在陌生的小鎮街道上躊躇不前。

就在這時候,他們看見空中有一道巨大的光柱揮舞,在夜色中劃出白灼的傷痕。這件事帶有一絲神蹟的味道,日後建國雖不是教徒,但至今仍對耶穌教心存敬畏。

「就去那裡吧。」父親這樣說。

於是他們慢慢走向光柱的所在。越靠近目的地人就越多,人們騎著腳踏車、機車、走路,或快或慢地向著光柱移動。現在他們大概可以判斷光柱的來源,那是鎮外的一塊荒地,荒地上空現在泛著陣陣光暈。郊外街燈稀少,他們像雨後夜晚的大水蟻群,著迷地向著房子內燈火振翅聚集。在黑暗的小徑中不知走了多久,他們開始聽見悶悶的音樂聲響,聲音越來越大,每個人的心臟都隨著低音鼓聲跳動。

小徑轉角之後,他們被荒地上的龐大景象淹沒。

荒地憑空生出了一座遊樂園,三層樓高的摩天輪掛著十個籠子,旋轉時嘎嘎作響,小小的燈泡每次閃爍都變化色彩。七八隻木馬隨著音樂節奏繞行圓柱,圓柱上畫著幾個只葉子遮住下體的白人。在馬鞍上飛馳的人假裝不經意地偷瞄畫中袒露的乳頭和胯下。木馬身上的油漆斑駁脫落,露出下面的紅鐵色肌底,鋼圈敲擊玻璃瓶口的清脆聲響,爆米花的氣味,印度女人用三種語言廣播節目和走失小孩的名字……每個角落都發出白灼之光,光線和空氣中隆隆震動的音樂互相摩擦,讓每個人的汗毛都根根豎起。那是他們從來無法想像的世界,那麼多的歡樂情緒,竟然可以濃縮在這樣一個破爛地方嗎?

遊樂園的門口有售票亭。父親走了過去,他跟著人群排隊,一點一點地靠近入口。小建國激動得雙腿發抖,他知道父親沒錢,但忍不住偷偷地希望他能從某個口袋的夾縫裡摸出幾個銅板。他想,只要能進去看一次,摸一摸那些色彩斑斕的太空船船身,這輩子睡在荒地上都沒關係了。

輪到父親的時候,父親問售票員:「你們還要請人嗎?」

售票員抬頭瞄了父親一眼,轉過身去喊老闆。

當時共產黨早就被趕入深林之中,馬來西亞經濟開始起飛,人人急著想要花掉手上的鈔票,巡迴遊樂園因此開始在半島流行起來。巡迴樂園是會移動的,那些煥發著美好之光的大怒神、碰碰車、海盜船、賓果攤……全都可以拆卸折疊成一塊塊巨大的零件和生鏽鐵架,裝進四五臺貨櫃車裡載走。貨櫃車隊在半島上四處游牧,尋找下一個可以停留的市鎮,然後他們再次清空一塊空地,把貨櫃裡的東西一一倒出。摩天輪架起後緩緩轉動、聚光燈妖嬈起舞,整個市鎮的大人小孩都被吸到這塊空地上,四台貨櫃車就能從荒原裡升起一個樂園。

樂園需要大量的人力,但願意應徵的人很少。薪資不高是其次,要長期離家四處遷徙,就不是每個人都願意的。然而建國父親正求之不得,雙方一拍即合,從此他們就在遊樂園住下了。建國父親當然沒想到,他們這樣一待就待了四十年,看著遊樂園從大熱到漸漸死亡,連自己也死在樂園裡。

不過這是後來的事了。

(在父親遺下的物品裡竟然翻出一份油印的小書,封面用紅字題着《論持·戰》。裡面墨跡斑斑,封底上潦草地寫滿筆記。)

我們說的還是父親剛剛進入遊樂園的年代。

建國和父親留下的巡迴樂園叫Paradise land,又叫Jannah,樂園地。樂園老闆是華人富商的兒子,年紀和父親差不多。老闆年輕時到過英國留學,書沒認真讀過幾頁,整天和一群馬來貴族四處鬼混,踢足球玩女人賭撲克。回到馬來西亞後正苦惱被老爸管得死死的,沒想到剛好趕上巡迴樂園的熱潮。他於是藉口要自己創業,砸下重金從英國運回來一批二手遊樂設施,從此在馬來半島四處風流逍遙。

父親在樂園裡的工作名義上是貨櫃車司機(十幾年後老闆才想起貨車執照的事,匆匆催父親去考),不過樂園人手不足,營業的時候也要當入門的售票員、遊戲攤攤主、或是在鬼屋裡面扮鬼。但到後來父親最主要的工作,是維修遊樂園裡面的機械。剛開始是因為老闆察覺技工在保養機器時,父親喜歡跟在旁邊看,偶爾還會這邊問問、那邊摸摸的。一向孤僻冷漠的建國父親願意主動和人攀談,這讓老闆感到十分好奇。於是後來有小故障,老闆就讓父親去試。他驚訝的發現建國父親對機械似乎十分熟悉,不但每次都能順利解決問題,遇到技工無法處理的疑難雜症,還能夠自己閱讀前任主人留下的殘破英文說明書,精確地找出毛病所在。從此以後,樂園的維修工作就都交給父親了。

老闆當然知道父親的來歷有問題,一個對機械熟悉,還讀得懂英文的男人,怎麼可能願意跟著遊樂園到處跑?不過換個方向思考,一個對機械熟悉,還讀得懂英文的男人,竟然願意跟著遊樂園到處跑,這不是天上掉下來的禮物嗎?

樂園裡維修保養的工作相當繁重,那些遠道而來的笨重器物顯然有一定的年紀,鏽跡像壁癌般爬滿每一寸外露的金屬表面,需要不斷上油補漆才能掩蓋年老力衰的呻吟。剝落的漆皮會露出三四層不同的顏色,像地質斷層一樣指向它們的前身。拆開外殼後,鐵器的內臟裡烙印著各樣看不懂的文字及號碼。有些看起來是歷任遊樂園主人加上去的:Wonderland,Happiness,Fairytale……他們耗盡各種描述歡樂的字眼為自己的樂園命名,然後破產變賣,下一任主人又絞盡腦汁地召喚出更為濃烈名字,以求覆蓋它們原來的厄運。裡面出現最多次的是EDEN,建國猜想這是樂園下南洋之前最後一個名字,樂園主人著魔一樣四處烙印EDEN,帶著蔓藤花式的字樣在每一件器物上都找得到,有的甚至凌亂地蓋在之前的名字上,在鐵器心臟裡融成一片血肉模糊的傷疤。

然而只要等到夜幕降臨,時間就會重新開始。他們抽打灌滿柴油的發電機,催逼它發出低沉竭力的喉聲,把燈泡和聚光燈推到幾近燒熔的極限,喇叭聲音高得嘶啞破裂,這時所有蒼老的痕跡就會銷聲匿跡。樂園的零件齒輪吃力地轉動,鼓動起巨大的絢麗幻境,昔日的榮光重新降臨。那是巡迴遊樂園的黃金年代,只要一開場就有源源不絕的客人,每天都忙得不可開交。不管是白人還是馬來人都是一樣的,凡勞苦擔重擔的都可以到這裡來,樂園裡從來沒有衰老,只有不斷的復活重生。

在那個幻象機器的核心是鬼屋,鬼屋是「樂園地」最大的賣點。那是樂園地裡最新的設施,裡面只有一個EDEN的烙印工整地按壓在馬達內殼上。這座鬼屋和別的不一樣,裡面沒有什麼亂七八糟的殭屍吊死鬼木乃伊,這些粗製濫造的恐懼根本不會持久。EDEN的主人花費了極大的心力,將它打造成一個依照《聖經》改編的真實寓言。客人一開始走進去會陷入一片黑暗渾沌,他們互相推搡不敢前進,然後有聲音說「要有光」,忽然就燈光刺眼,大家發現自己置身於一片青草地上,布幕上畫著一個沒穿衣服的金絲貓餵男人吃蘋果。

眾人強忍著眼淚和害臊往前走,沒走幾步,旁邊跳出幾個全身塗成紅色的,頭上戴著牛角的男人。幾個怪物哇哇亂叫,大家笑著叫著往前跑,卻發現自己陷入鏡子的迷宮裡。紅色的魔影在四處攢動,燈光開始閃爍,喇叭發出雷聲隆隆,眾人每次想前進就被自己的倒影撞上。膽小的小孩尖叫哭泣,大人罵著:「不要擠!不要擠!」。好不容易走出迷宮,卻又踏進一片火紅地獄,暗影重重,人們被後面的追兵逼得走投無路,唯一可以前進的方向是一道獨木橋,橋下是紅色的鮮血湖泊。有聲音說:「這是我的血,為你們……

每個走出鬼屋的人都心有餘悸,他們恍惚地看著外頭歡樂的景象,產生已經死過一次的錯覺。離開樂園回家後,他們後續幾個晚上在睡夢中驚醒,忽然為自己此生的罪孽感到焦慮,同時又為活在這個真實的世界感到慶幸。

這是EDEN主人最後的設計。

當然,這樣的故事不可能在馬來西亞上演。樂園地老闆為了吸引客群,也為了避免「馬來豬來搞搞震」,勢必要對鬼屋進行一番改造。但鬼屋裡的構造相互牽引,要做任何改動都牽連甚廣。在老闆苦無對策的時候,父親提出了影響樂園未來的改造計劃。

父親的改造計劃十分簡單,鬼屋原來的機械和道具原封不動,只是將原來的聲效對白重新配置了一遍,附上三種語言的翻譯。在馬來語的翻譯裡,故事被改成了可蘭經版的創世紀:Eden變Jannah、Satan改成Iblis,在Adam的名字前加個nabi……鬼屋搖身一變,成為穆斯林的天路歷程。這是當時全國第一個伊斯蘭教主題鬼屋,在馬來人多的地區極為轟動,某州蘇丹的王子還帶著侍衛來包場玩過,老闆親自下場扮油鬼仔,落力的演出嚇得王子一群人走出鬼屋後立即跪地祈禱叩拜,還上了全國報紙的地方版。

自此之後鬼屋每晚都大排長龍,不只是馬來人,華人和印度人也都蜂擁而至,每個進去鬼屋的人都聽到自己想聽的版本,然後三大種族一起嚇得屁滾尿流地跑出來。小小一個鬼屋成功融合了馬來西亞的各大種族,電視和報紙都派人來採訪了幾次,讓老闆賺足了面子和鈔票,高興得合不攏嘴。

然而父親卻越發沉默了。父親不吸煙不喝酒,除了偶爾買點雜貨之外連樂園的大門都不會離開。他每天眉頭深鎖地埋頭工作,晚上幫忙樂園營業到深夜,白天大家還在睡覺,他卻早早就起來,拿著工具箱四處檢查敲敲打打。也因為這樣惹得眾人抱怨連連,私底下叫他「死老猴」、「老烏龜」,只是因為老闆看重父親,大家才不敢和他起衝突。建國不清楚父親是否知道大家對他的不滿,這些年來,連建國都很少聽見父親說話。大概也因為這樣,父親從未再娶,到八十歲還是一個人。父親活得像是苦行,在他的身體上看不見半點慾望的痕跡。

建國就不一樣了,作為樂園裡唯一的孩子,建國備受眾人寵愛。在居無定所的遊樂園裡當然不能上學,可是建國從不同的人身上學會了各種語言。最主要的老師是印度人薩拉華迪,薩拉華迪是樂園裡面的廣播員,加上方言的話總共會十二種語言,還能精確地模仿各地華人的口音。(小時候他們經常玩這樣的遊戲:一個爸爸是潮州人,媽媽是客家人,小時候被廣東人奶奶照顧的小孩,他怎麼說「我大便後屁股沒有洗乾淨」?

(啊,年老薩拉華迪現在不知道在哪?

年紀稍長,他開始攀爬一切看得到的東西。先是碰碰車的頂棚,然後是旋轉木馬的柱子,最後是摩天輪的最頂端。摩天輪不停地轉,建國必須比圓弧的轉速更快才能停在頂端,他聽見血液沸騰時在耳邊啪啪作響,雙臂的肌肉賁張突起,大批的人群在下面驚呼。建國倒掛在摩天輪籠子上緩緩降落,接受眾人的歡呼。

遊樂園是建國的領土,他在這裡可以自由地飛行穿梭。建國可以在十米外精準地射中獎品娃娃的左眼,倒立著丟鋼圈也能套住正中央的玻璃瓶,魚竿一甩同時撈起四五隻獎品塑料鴨子……建國像在森林裡長大的男人一樣,肌肉結實動作靈敏。他表演的時候眾人看得如痴如醉,喝彩聲不斷。

當然,也有不少年輕的媽媽、帶著弟弟來樂園玩的女學生,吃吃笑著跟建國走到鬼屋背後的陰暗處……

不表演的時候,建國跟著父親學維修機械。父親依舊沉默寡言,他默默地做,讓建國照著他的樣子學。雖然沒有學過什麼理論,但建國學得很快,像是對機械有直覺般的靈敏度。該怎麼說呢,他只要一模就能感覺到機械的內裡的溫度。遊樂園是有生命的,所有機械壞掉都不會平白丟棄,既然不可能從歐洲運回零件,他們就只能依照手邊有的材料去代替改造。遊樂園慢慢長出自己的樣子來,有時拼拼湊湊地,還能生出另一個玩具出來。

建國很早就能感受到遊樂園有自己的生命,它會擴張、旋轉、繁殖,當然也會死亡。

死亡原來就是遊樂園的本體,人們之所以要到遊樂園,期待的就是死亡。就像撐起巨大快樂的是這些沉重衰老的機器,在那狂歡表象下的每次升空、墜落、尖叫,都是人面對死亡面容之前的練習。等到他們多玩了幾次,腎上腺素漸漸消退,死亡就忽然變得索然無味了,人好像終於找回了面對現實的勇氣。任何事物停滯久了都會死亡,人流漸漸減少,遊樂園的生命也開始流失。但巡迴遊樂園並不害怕,只要再次拆卸自毀,它們換個地方就可以重新活過來。等樂園再次回到同一個地方,上一代人早已記憶衰退,下一代人會重新感到興奮,一直到時間被耗盡為止。

樂園從來就不會死亡。當英國運來的零件逐漸耗損敗壞,建國和父親用當地的材料重新建築,只要這樣不斷地重新組合,他們就有了無限多的可能性、無限多的樂園。建國因而從來不會對遊樂園感到厭倦,他一直對樂園死亡又重生的過程深深著迷。他原來以為自己會像父親一樣,這輩子都不會離開樂園的。

然後時間好像忽然被耗盡了。

九零年代以後,大型的主題樂園開始越來越壯大,巡迴遊樂園的簡陋設備不再能夠吸引人進來。之後陸續傳來巡迴遊樂園弄死人的報導,大家開始質疑樂園的安全性(裡面真的有工程師嗎?),更加沒有人願意來了。老闆年紀大了,娶了老婆生了兒子,繼承家族財產後懶得再管這盤賠錢的生意。但遊樂園成為一塊巨大的廢鐵,要賣也無從脫手。幸好老闆感念舊情,讓遊樂園停在他們家族的空地上,依舊讓父親生活在裡面。

建國知道是時候離開了。

當時已經快四十歲了,建國身無長技,沒有任何證書,根本進不了主題樂園工作。想過要去街頭賣藝,結果剛開始爬上吉隆坡塔就被警察抓回去,罰了幾千塊。

幸好建國還有一身用不完的力氣。那幾年炒地皮的熱潮開始,全國上下都有新建案工地,建國會焊接、水泥、木工,一個人頂得上十個孟加拉外勞,重點是警察來了也不用逃跑,因此大受承包工頭的喜愛。再過幾年後,中國人買下了首都,帶著現金像買雜貨一樣掃下大片的房產。建國每天都有做不完的工作,連女人都沒時間想。他好像回到了過去的生活,再次全馬來半島奔波,四處去建設祖國。

建國很久沒有想起父親,再次想起來,是因為老闆打電話來說樂園出問題了。

建國隱隱感到不安。抽了個空回到樂園最後停留的地方,發現偌大的摩天輪、海盜船、木馬全都消失不見,只剩下一個鬼屋。鬼屋變得比原來還要大,層層疊疊地長出不同的枝節,像是將樂園吞吃了一樣。

建國推開鬼屋的門,發現裡面一片漆黑。

「阿爸?」

聲音空蕩蕩地迴響,建國終於想起自己是個孤兒。

“樂園” first appeared in 道南文學 /第 37 屆, 2018, and is published in《廢墟的故事》(雙囍出版,2021)

此篇小說曾獲37屆 道南文學獎小說首獎,後收入《廢墟的故事》(雙囍出版,2021)

Paradise

A tale should be told from the very beginning, but Kian Kok doesn’t know much about the story’s start. After Father vanished, what Kian Kok thought of as certainties silently slipped and slid too, like buildings erected on sandy soil by heartless developers. People ate in those houses; they made love and cleaned their toilets, days and years passing without incident. One day, they returned home as usual and noticed something off-kilter. Anxiously, they rapped on surfaces and put their ears against walls, sensing budding cracks in the engorged interior. But they couldn’t locate the root of the problem. At night, they went to bed with their hearts in their mouths, and they held back even when spanking their children.

By the time the first crack bloomed across the wall, the house had sunk to its knees, and they realized it was too late.

A problem can only be solved by tracing its origins. That’s what Kian Kok’s many years of experience tell him.

And speed is of the essence. It would be too late otherwise.

The first verifiable fact: Kian Kok’s mother had never been around. Yet a mother’s disappearance can take many forms. Had she died from an illness? Run off with another man? Could it have been complications during childbirth? Whenever the question was raised, Kian Kok’s father would clam up, his face darkening. Kian Kok’s father was always reticent, and he especially disliked bringing up his past. Kian Kok thought this was only natural. After all, the man was a widower almost his whole life, dragging around a sniveling ball and chain. If Kian Kok were in his shoes, he’d be sick of the world, too.

(Could this explain the silent vanishing?)

Where was Father’s hometown? Kian Kok could only venture a guess. Father’s accent hinted at the northern part of Peninsular Malaysia. But for as long as Kian Kok could remember, their home was on the southern tip of the peninsula, Johor. Because Father wasn’t in the best of health, and moreover, had a kid in his care, he could only earn pennies doing casual odd jobs here and there. Kian Kok could clearly recall all the times they had to move. It usually happened at night. Little Kian Kok would be shaken awake from his dreams to discover all his belongings packed away in luggage, a sure sign it was time to go. Of course, more often than not, they were getting kicked out. But even when a kindhearted landlord didn’t mind them sticking around, Father would quietly leave with Kian Kok after a short stay.

They moved steadily south, sometimes switching places every few days, as if fleeing disaster.

Now that Kian Kok thinks about it, that was probably exactly what they were doing.

(And what about now? Isn’t the war long over?)

One day, the carnival appeared along the route of their migration. The story goes that Kian Kok’s father had once again been evicted by a landlord. Little Kian Kok asked where they would go next. Father did not reply. Night had well fallen by then. The two of them loitered on the streets of the unfamiliar town, a big suitcase by their feet.

It was then that they saw a gigantic pillar of light swaying in the air, inflicting incandescent wounds on the dark sky. The whole thing had a whiff of the miraculous about it. Although Kian Kok never became a believer, to this day, he harbors a secret respect for Jesus. “Let’s go there then,” Father said.

So they moved slowly toward the pillar of light. The closer to their destination, the bigger the crowds. People walked, or else rode bicycles or motorcycles, heading toward the pillar each at their own pace. Father and son could now approximate the source of the brightness. A patch of abandoned land lay right outside town, and the aurora sparkled above this wasteland. They were in a rural area with scant streetlamps. People appeared like swarms of flying ants after rain, flapping their wings and scuttling toward brightly lit homes. Muted music soon reached their ears, growing louder by the second. Everyone’s hearts began thumping to the beat of the bass.

They rounded a corner on a narrow path. The scene on the wasteland, larger than life, overwhelmed them.

A carnival had popped up out of the blue. Ten capsules hung from a Ferris wheel a whole three stories tall. When the wheel turned, it creaked noisily, tiny light bulbs changing colors whenever they blinked. Seven or eight wooden horses circled a pole to the music’s rhythm. Riders galloping on saddles surreptitiously stole glances at the white people painted on the center pole, each naked but for a single leaf covering their privates, nipples laid bare. The paint was peeling in strips from the horses, exposing the rust-red subcutaneous tissue underneath. All around rose the crisp dings of steel rings knocking against glass bottles, the aroma of popcorn, an Indian woman’s voice broadcasting the schedule of events and the names of lost children over loudspeakers in three languages . . . From each and every corner blared white-hot heat, beams of light rubbing against sound waves vibrating thunderously in the air, raising the hairs on everyone’s forearms. It was a world they had never imagined. How could so much joy and excitement be condensed into such a shitty place?

A ticket booth stood by the carnival’s entrance. Father got in line like everyone else and edged closer and closer to the front. Little Kian Kok’s legs trembled with agitation. He knew Father was broke. Still, he couldn’t help wishing Father could materialize a few coins from the seams of one of his pockets. Just once, Kian Kok thought. If he could only brush his fingertips against the colorful spaceships once, he wouldn’t mind sleeping on wastelands for the rest of his life.

When Father got to the head of the line, he asked the ticket seller: “Are you still hiring?”

The ticket seller looked Father over, then turned around to summon the boss.

By that time, the communists had long been chased into the depths of the jungles. The Malaysian economy was taking off; everyone was desperate to spend the cash burning holes in their pockets. This marked the ascent of traveling carnivals. These funfairs were mobile. The drop towers, bumper cars, pirate ships, game stalls . . . all those shimmering beauties could be broken down into huge components and rusty iron racks to be ferried away by four or five cab-over trucks. The fleet roamed the peninsula in search of its next resting place, after which a patch of unused land would be cleared, and everything would tumble out of the truck containers. The reassembled Ferris wheel would revolve slowly. Everyone in town, young and old, would be drawn to the clearing by the spotlights’ alluring dance. To think: just four trucks were enough to conjure a paradise from a wasteland.

Though the carnival demanded lots of manpower, the number of job applicants was lacking. Low wages were one thing. More importantly, not many could put up with the long-term rootlessness, the constant moving around. Yet, this was precisely Father’s dream scenario. He was a perfect fit. That was how father and son made the carnival their home. Of course, Father had no idea that they would go on to stay four decades, bearing witness to the carnival’s slow death as it descended from its height of popularity. Certainly, he never thought he would die with it.

But that’s something that happens much later.

(Among the things Father left behind, there was unexpectedly a little mimeograph with the words “Protracted War” printed in red on the cover. The pages bore smears and blots of ink. The back cover teemed with scribbled notes.)

We’re talking about the early days, when Father had just joined the carnival.

The mobile funfair Kian Kok and his father entered was called Paradise Land, and also Jannah. The owner was about Father’s age, the son of a wealthy Chinese merchant. In his halcyon days, the boss had studied abroad in England, though he didn’t spend much time hitting the books. Instead, he goofed around with a bunch of Malay royalty, kicking soccer balls, chasing women, throwing down poker cards. Upon returning to Malaysia, he found himself frustratingly under his dad’s thumb, but happily the traveling carnival fad came along just in time. Using entrepreneurship as an excuse, the son exchanged a small fortune for a set of secondhand carnival equipment shipped all the way from England. Thus began his carefree days gallivanting about peninsular Malaysia.

Father’s official job description was truck driver (it wasn’t until ten years later that the question of a driver’s license struck the boss, who hastily urged Father to apply for one), but because of the worker shortage he also wore the hats of ticket seller, game stall operator, and haunted house ghost, as the occasion demanded. Later on, his main duty became fixing and maintaining carnival equipment after the boss noticed Father hanging around the technicians sent to perform routine servicing. Occasionally, Father would even ask questions, his hands caressing this or that part. These sparks of extroversion aroused the boss’s curiosity, since Father was usually reticent and aloof. So the boss started having Father take a look when they encountered hiccups with the equipment. To the boss’s surprise, Kian Kok’s father seemed to have an innate familiarity with machinery. Not only could he patch minor issues, but he could also pore over tattered English manuals left behind by the previous owner whenever there were bigger malfunctions that even the hired technicians couldn’t handle. With the manuals as guides, Father could always pinpoint the root of any problem. Soon, all of the carnival’s repair and maintenance work was heaped upon him.

Of course, the boss understood something was off. Why in the world would a man deft with machines and fluent in English, be willing to lead a rootless life? But put another way, wasn’t it heaven-sent that a man deft with machines and moreover, fluent in English, would be willing to run around with the circus?

Maintaining the equipment was a heavy responsibility. Those unwieldy machines from an ocean away had obviously seen their day. Cancerous rust stains crawled over every inch of exposed metal surface, requiring incessant coats of paint to cover up the machine’s sickly, ancient moans. Where the paint peeled, three or four different shades could be seen underneath, previous incarnations visible, like looking at a cross section of the earth. The machines’ innards laid bare strange marks when stripped of their outer shells, displaying indecipherable words and symbols that had probably been imprinted by previous owners: Wonderland, Happiness, Fairytale . . . The owners exhausted various descriptors of joy to christen their respective carnivals. Then came bankruptcy and resale, followed inevitably by the next owner racking their brains to summon an even more piquant name to paper over the carnival’s ill fate. The title that popped up most often was “EDEN,” which Kian Kok guessed was the carnival’s final moniker before it sailed to Nanyang. As if possessed, EDEN’s owner branded the word, stylized with vines, on every available object. It could even be found stamped over more ancient names, all those different titles melting into gory wounds over the machines’ hearts.

Yet time would restart as soon as night arrived. The carnies flogged generators overspilling with gasoline, coaxing out throaty shrieks as the light bulbs and spotlights were pushed to melting point. When the loudspeakers screamed at the top of their lungs, they erased all traces of the carnival’s dilapidation. Each cog and wheel spun laboriously to sustain the enormous mirage and bring back the glory of the past. It was the traveling carnival’s golden age. Each day brought unceasing waves of visitors as soon as doors opened. White or Malay, there was no difference; anyone who labored and chafed under their burdens could come to the carnival, where there was no aging, only incessant rebirth.

At the core of that fantastical machine lay a haunted house. It was Paradise Land’s biggest selling point. Being its newest facility, the haunted house had only one name, EDEN, neatly embossed upon its motor’s shell. This haunted house was one of a kind. No Jiangshi and hanged men thrown discordantly together with mummies; such rudimentary horrors could not last. Instead, EDEN’s owner had poured heart and soul into creating a genuine fable adapted from the Bible. Visitors were first plunged into total, murky darkness. They’d shove each other, shuffling their feet in fear. Then a voice would say: “Let there be light.” In sudden, piercing brightness, everyone would find themselves within a meadow. On a cloth backdrop was depicted a naked golden cat feeding an apple to a man.

Holding back mounting terror and tears, the crowd pressed forward. They had taken only a few steps when they were ambushed by horned men covered head to toe in red paint. As the creatures howled gibberish, everyone laughed and ran ahead, only to find themselves trapped in a maze of mirrors. All around them jostled red demonic figures. The lights flickered to the roar of thunder pumped through loudspeakers. Whenever the people tried to move forward, they bumped into their own reflections. Timid children began to scream and wail. “Don’t push! Don’t push!” scolded the adults. When they finally managed to exit the maze they stepped straight into a fiery hell full of overlapping shadows. Cut off from retreat by pursuing monsters, the crowd had only one route of escape: a narrow wooden bridge suspended over a scarlet pool of fresh blood. A voice sounded. “Drink this, all of you. This is my blood…”

Dread lingered in the hearts of everyone who walked out of the haunted house. Gazing upon the scenes of joy outside, they acquired the dazed feeling that they had already died once. After leaving Paradise Land for home they jerked awake several nights in a row, harboring deep anxiety about the sins they’d committed in their current life. At the same time, they were grateful for living in this solid, real world.

Thus was the final design by the owner of EDEN.

Of course, such a tale could never take the stage in Malaysia. To attract tourists, and also to avoid “those meddling Malay authorities sticking their snouts in,” the carnival’s latest boss had no choice but to revamp the haunted house. But the house was configured in an interlocking way, such that any change created ripples throughout. Just when the boss was out of ideas, Father suggested a renovation plan that would forever alter the carnival’s future.

Father’s idea was very simple indeed. The haunted house’s original machinery and mechanisms were left untouched. The only element that changed was the voiceover, which now came with translations in three languages. In the Malay version, the narrative was transformed into the Quran’s tale of genesis: Eden became Jannah, Satan turned into Iblis, and Adam acquired the Nabi honorific tacked in front. In the blink of an eye, the house became a Muslim pilgrimage. The nation’s very first Islamic-themed haunted house caused quite a stir whenever it arrived in Malay-majority areas. Once, a crown prince of some Sultanate even booked the whole place for him and his attendants. On this occasion, the boss rolled up his sleeves to take on the role of an orang minyak, a performance so convincing that the prince’s entourage immediately knelt on the ground and started praying as soon as they exited the haunted house. The royal outing even made the regional section of a national newspaper.

From then on, the haunted house attracted snaking lines every evening. It wasn’t just Malay people. Chinese people and Indian people too descended in tidal waves upon the haunted house. Inside, they each heard the version they wanted to hear, after which all three major ethnic groups scrambled out, leaking pee and farts from being scared silly. Thus a tiny little haunted house managed to harmonize Malaysia’s various ethnicities. TV and newspaper reporters arrived to conduct interviews. Flush with cash and prestige, the boss grinned from ear to ear.

But Father grew only more silent. He neither smoked nor drank. Besides an occasional grocery trip, he never even left the carnival’s entrance. Each day, he buried himself in work, brow furrowed. And each evening, he helped out with the carnival’s operations well into the night. While the other carnies slept in, he woke up at the crack of dawn to putter around, toolbox in hand. His banging and tapping drew everyone’s ire. They called him “stupid old monkey” and “grandpa turtle” behind his back. They’d have confronted him if he weren’t so important to the boss. Kian Kok didn’t know whether Father was aware of everyone’s dissatisfaction. Even Kian Kok seldom heard a peep out of his father. It might be why Father never remarried, staying single into his eighties. He led his life as if he were an ascetic monk, no hint of desire upon his person.

Kian Kok was a different story. As the only child in the carnival, he was the apple of everyone’s eye. There was, of course, no way for him to attend school while wandering about with the carnival. But he did learn multiple languages from various people. His main teacher was the carnival’s Indian announcer, Saraswati, who knew a total of twelve languages including dialects, and could accurately mimic many regional Chinese accents. (They used to play this game when Kian Kok was little: If a child with a Teochew father and Hakka mother were brought up by a Cantonese grandma, how would said child pronounce, “My butt wasn’t washed after I pooped?”)

(Ah, where could Saraswati be now, aged and wizened?)

As he grew older, Kian Kok began to climb everything in sight. First, it was the bumper car canopy, then it was the carousel pole, until eventually he reached the very tip of the Ferris wheel. To remain atop the spinning wheel, Kian Kok had to sustain a speed faster than its revolution. His ears rang with the roiling of his blood. Bulky muscles popped from his arms, while far below the huge crowd screeched. He accepted the public’s adoring cheers as he made his slow descent, dangling upside down from a Ferris wheel capsule.

The carnival was Kian Kok’s dominion, a place he could zip and fly through freely. It was child’s play for him to shoot out the left eye of a game stall doll from ten meters away, or to snag four or five plastic duck prizes with one sweep of his rod; not to mention tossing a ring right onto a glass bottle in the dead center of the formation, all while standing on his head . . . Like a man raised in the jungle, Kian Kok was brawny and spry. His audience grew drunk on his performances. They cheered him on from start to finish.

In due course, quite a few young mothers giggled their way to the shadows looming behind the haunted house with Kian Kok. Sometimes girls in school uniforms took their place, younger brothers in tow . . .

When he wasn’t performing, Kian Kok apprenticed with his father in machinery maintenance. As always, Father kept up his silence, going about his business mutely, letting Kian Kok learn from example. Although they never followed any theories or syllabi, Kian Kok picked things up quickly, as if he had an instinctual sensitivity. How to describe it? He could feel the machine’s inner temperature with just one touch. The carnival was imbued with life. When a machine part broke, it was not readily discarded. Since they couldn’t obtain new parts from Europe either, all they could do was craft replacements with whatever materials they had at hand. Slowly, the carnival began to take on its own look. With enough spare bits, sometimes it even sprouted new toys.

Very early on, Kian Kok sensed that the carnival had a life of its own. It could expand, twirl, and breed, which of course, meant it could also die.

Death was, after all, the carnival’s true form. People visited precisely because they expected demise. Behind the scenes of each ecstatic ascent and screaming plunge, people were actually rehearsing how they would face death, while those cumbersome, ancient machines worked to prop up such incredible happiness. Then after a few visits, the adrenaline receded. Suddenly death became mundane—it was as though people finally found the courage to face reality again. Any object at rest for too long would meet its end. As the crowds thinned, so the carnival’s life force leached out. But the traveling carnival was not afraid. As long as it committed self-destruction, it could come alive once more in a different place. Even if it returned to a previous spot, the memory of an earlier generation would have long since paled, while a new generation would rediscover elation, so on and so forth until time itself was depleted.

The carnival never would die. When the worn cogs and wheels from England gradually broke down, Kian Kok and Father used local materials to reconstruct them. And as long as this reconfiguration kept taking place, they had on their hands an infinite carnival, full of infinite possibilities. So Kian Kok never grew tired of the funfair. He was deeply mesmerized by its cycles of death and rebirth. He actually thought he’d spend his whole life in the carnival, just like Father.

And then, time abruptly seemed to be depleted.

The ranks of mega theme parks grew ever larger after the nineties. People ceased to be dazzled by traveling carnivals and their primitive equipment. Then came successive news reports about fatal accidents in mobile funfairs, which led the public to question carnival safety (did they really have engineers on staff?) Soon there were no willing visitors. The boss was older now, married with kids. After inheriting his family’s fortune, he no longer had reason to give two shakes about this money pit. But now that the carnival had been reduced to a gigantic mound of metal scrap, there was no way he could sell it to somebody else, either. Luckily, the boss was a sentimental sort. He parked the carnival on a piece of wasteland deeded to his family, and allowed Father to continue living there.

Kian Kok knew it was time to leave.

He was almost forty by then. With no employable skills or diplomas to speak of, he couldn’t find work in the theme parks. Then he thought about becoming a street performer. He’d barely started scaling the KL Tower before the police dragged him right off and slapped him with a fine of several thousand ringgit.

Luckily, Kian Kok had boundless physical strength. Real estate was just heating up then, new construction mushrooming all over the country. Kian Kok could handle welding, cement work, and carpentry. He was as strong as ten undocumented workers, and more importantly, he didn’t have to make for the hills when the police came knocking. For this reason, he was the darling of general contractors. A few years on, Mainland Chinese investors descended to sweep up the entire capital, buying swathes of real estate in cash as if shopping for groceries. Kian Kok was so busy with work he didn’t even have time to think about women. Roaming all over Peninsular Malaysia, he seemed to have reverted to a previous life, except now he was traveling to erect his fatherland.

It had been a long time since he thought about Father. When that figure next crossed Kian Kok’s mind, it was because the boss called to say something was wrong with the carnival.

Kian Kok felt a vague unease. When he had a moment’s downtime he returned to the carnival’s final resting place. The hulking Ferris wheel had disappeared, as had the pirate ship and wooden horses. The only thing standing was the haunted house, which had grown larger than its original size, incongruous layers and outcrops protruding as if it had swallowed the rest of the carnival whole.

Kian Kok pushed open the haunted house’s door. It was pitch dark inside.

“Ah Ba?”

His voice echoed emptily. Kian Kok finally remembered he was an orphan.