etc.books founder Akiko Matsuo on building a space for feminism and solidarity in Tokyo

July 26, 2023

This essay is part of Transpacific Literary Project’s monthly column.

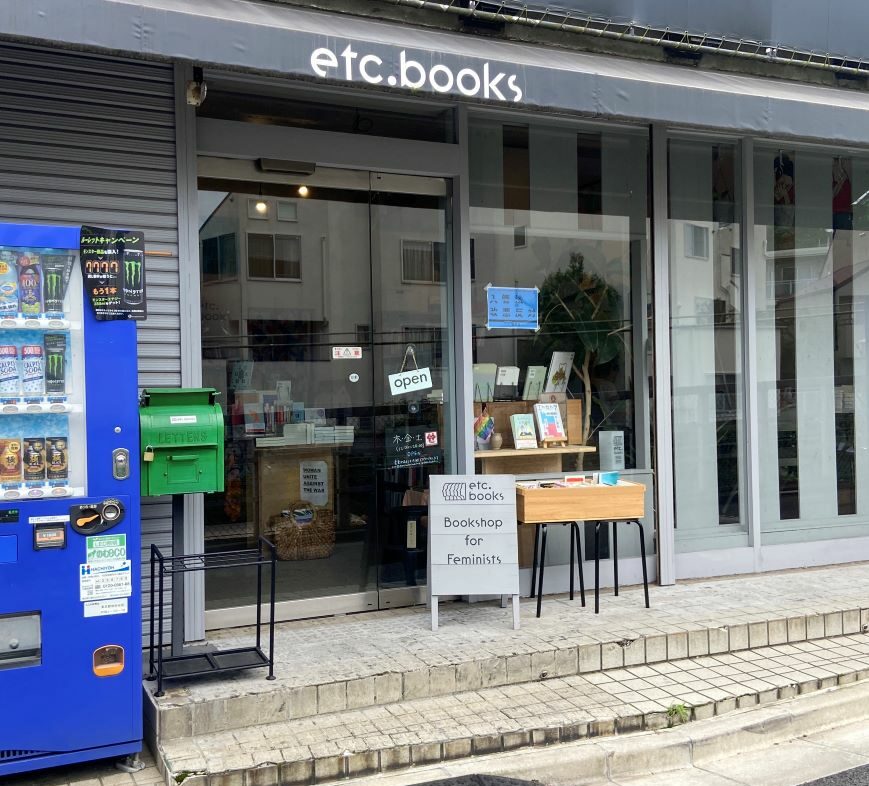

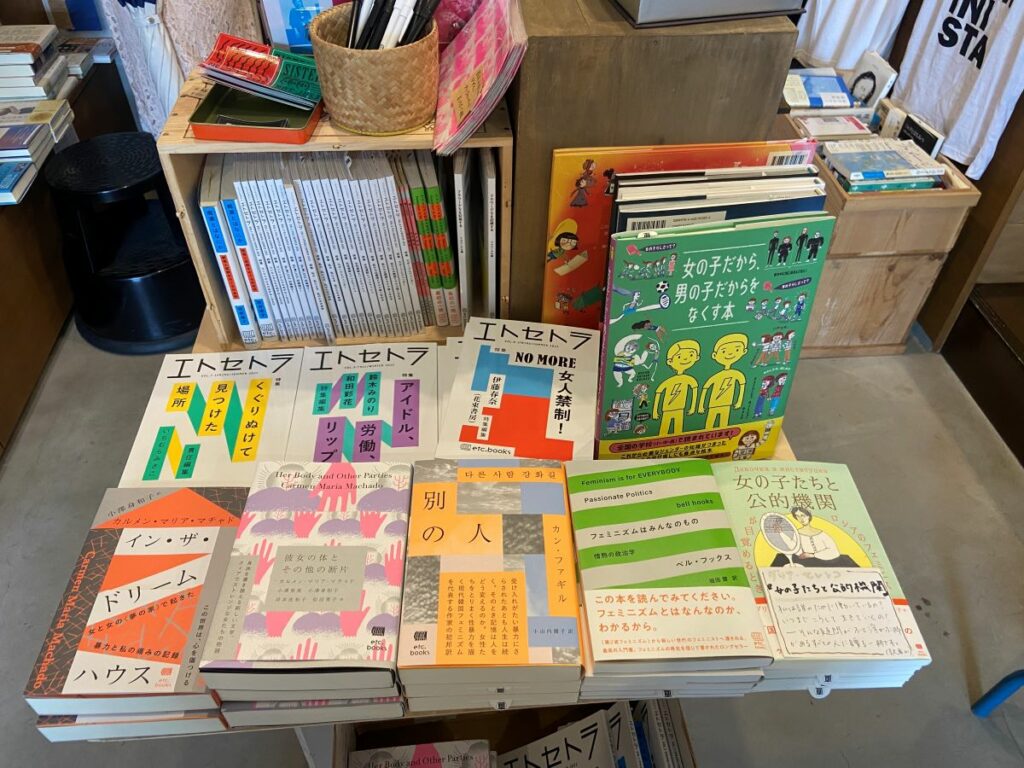

etc.books is both a publishing house and bookstore based in Tokyo, and it’s one of the only spaces still in operation in Japan that is dedicated to feminism. The publishing house, founded in 2018, publishes Japanese translations of seminal works such as Hotta Midori’s translation of bell hooks’s Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics, academic monographs, and their own magazine, etc., through which guest editors curate pieces on topics ranging from adult magazines to gender in sports.

The bookstore, which opened in 2021 not far from the Shin-Daita Station, houses the press’s offerings alongside a selection of children’s books, manga, and feminist works covering art, politics, sexuality, and more. It also hosts events, such as a Wen-Do self-defense workshop, as well as book club meetings and literary events.

etc.books borrows its name from Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Aoko Matsuda, a contemporary Japanese feminist author and regular collaborator with etc.books, chose the name, citing Butler’s concept of “illimitable et cetera” as a way to understand the space as one for marginalized voices in a patriarchal society. Illimitable and undefinable, the vision of feminism at etc.books is engaged both deeply on the ground and in creating new transnational and intersectional dialogues.

My interview with the founder, Akiko Matsuo, reflects this part of etc.books’s worldview. Weaving between Japanese and English, Matsuo and I moved gently through various gaps in language, occasionally using Google Translate as an interlocutor. In the space where language could not convey all of our meanings (a daunting task for us as writers and editors), we spoke between registers, trying to explain complex movements and historical moments in simple ways that could still relay their truth. We shared thoughts about contemporary feminism in Japan and approaches to translation and publishing.

Emilia Wang (EW)

What thoughts and experiences led you to decide to start etc.books?

Akiko Matsuo (AM)

I worked for Kawade Shobo, a big and classic publishing company with a long history, for fifteen years. I was working there on novels as well as books about feminism and gender. Then, around 2010, a lot of women started talking about feminism and gender issues on Twitter, or rather, started posting on Twitter about the books I published.

It felt rewarding to see all the posts and feedback about the books. I thought it would be easier to reach people more directly if I did it on my own instead of working for a big company. And so I decided to go independent.

Another issue that pushed me forward was the Tokyo Ika Daigaku issue in 2017, which revealed that Tokyo Ika Daigaku (Tokyo Medical University), one of the most prestigious medical schools in Japan, had been deducting entrance exam points from female applicants.

My friends and I held a demonstration in response. In Japan, wouldn’t you say there aren’t really many protests? [laughs]

EW

Yeah, that’s true.

AM

It was my first time holding a protest, too. But then our protests got on the news. And this really pushed me, and I thought, I have to make a clear statement about feminism and against sexism. And for that reason, I thought it would be better to have a feminist publishing company than a big company. It’s very important to state and show to the world that there is a feminist publishing house rather than work for a big company.

I had originally already decided to go independent before the protests, but I didn’t decide whether the company would be just about feminism, or other subjects as well. I was not sure if I could take on the responsibility. But after the protests, I felt that I needed to state that the publishing company would specialize in feminist issues.

EW

What did you want a space like etc.books bookstore to be?

AM

We wanted to make our place a safe place. There used to be a feminist bookshop in Japan, you know! There was one in Osaka…

EW

But it’s closed now, right?

AM

Yes, so I thought it would be nice to have a place where feminists could come at any time. We do talk events around once a month. And sometimes we have a small book club and small exhibitions.

Sometimes a woman who grows vegetables and herbs sells them here. Then people from the neighborhood come to see what’s going on, and they come in. But most of our customers come from far away. We sell vegetables so the neighbors will come, too [laughs].

EW

How many books do you publish in a year?

AM

Hmm, two or three books? And two magazines. I’m pretty busy [laughs]. But my colleagues run the bookstore, so I focus mainly on publishing.

EW

etc.books has published many different translated books. Could you explain how the selection process works?

AM

I started this publishing company by myself. Now I have two other colleagues. One of us is the manager of the shop, I am the publisher, and the other one helps with both the bookstore and publishing house. Because there’s only three of us, we have to be very selective about what we publish.

Originally, there was a publisher in Japan focused on gender issues called Shinsui-sha, which was a one-woman company. But the woman passed away, and the translation of bell hooks’s Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics went out of print—the book was no longer available in Japan. bell hooks is a writer whom I cherish very much, so I had to republish it. I approached this as if I was taking over the feelings of the original publisher.

Within the topic of feminism, I think sexual violence is the most important issue. We published フラワーデモを記録する (furawādemo wo kirokusuru) (Documenting the Flower Demo) by Masako Makino, which is a written and visual record of these public protests against sexual violence that are called the Flower Demo. We also published 別の人 (Betsunohito) (A Different Person), a Korean novel by Kang Hwa Gil and translated by Sonoko Osanai. It is also a book about sexual violence.

We also published a Japanese translation of Russian author and activist Daria Serenko’s Girls and Institutions (女の子たちと公的機関: ロシアのフェミニストが目覚めるとき) (Onnanokotachi to kōteki kikan: Roshia no feminisuto ga mezameru toki). This was translated from Russian by Satoko Takayanagi, who is a wonderful feminist.

It’s really important to me to work with feminist translators. Oftentimes they suggest books that they really want to translate, and then I say, “Let’s publish it.”

EW

As someone who doesn’t work as a translator, how do you approach publishing translated works?

AM

I believe all books are a form of dialogue with lives that are different from our own. So it is important for me to interact with, deepen, and learn about differences, especially from a foreign culture.

But I’m not a translator. Rather than translate, I like to face words head-on. And so, I like to edit.

I’m learning Korean right now, but I need to study English more, too. There’s a book I’m editing that’s originally in Korean. Although I am not a translator, I check the original as part of my job. It makes me think about the words more than if they were only in Japanese, and the words enter me more deeply. And since doing this lets me encounter Korean words for feminist concepts, I want to know and think about it. All the translators I work with are excellent translators and feminists, so I can trust them.

On one hand, I can widen the scope of translated books in Japan, but I also think Japanese issues are equally important.

EW

Could you talk more about the current state of gender violence in Japan?

AM

Yes, of course! Do you know about 痴漢 (chikan) (public molestation, commonly groping)? etc.books published a book titled 痴漢とはなにか (chikan toha nanika?) (What is Chikan?) by Masako Makino.

Currently, there is no law to forbid chikan. Yes, the constitution is about to be “changed,” but out of all developed countries, we are probably the most behind in terms of criminal laws about sexual violence. There are a lot of cases of it, but they are not brought to light. Official numbers say that Japan has fewer sex crimes than other developed countries, but this is only because chikan is not classified as a crime.

In fact, there are many cases of sexual violence, especially among women and sexual minorities. And of course, men have experienced sexual violence, too. I think all women in Japan have experienced at least chikan or even verbal sexual harassment…

EW

What does Masako Makino write about how to deal with this problem?

AM

It’s quite simple. She states that chikan is a crime.

Of course, many of the perpetrators are male, but another element of the problem is that Japanese society has neglected chikan, either ignoring it or downplaying it with humor.

It’s everyone’s responsibility. Our society has not considered it to be important.

EW

The magazines etc.books has published are very thought-provoking. I was especially moved by the edition about homeless women. How did you start thinking about this topic? And how have you been choosing the topics for the magazine in general?

AM

Really, this is also about timing. Rather than making a planned decision to do this or that, I just decide twice a year.

For the homeless issue that we published in spring/summer of 2022, it was the time after COVID-19 started. People were really running out of places to live, and I wanted to think about the concept of place.

We also published a special issue on sports and gender, which was in response to the Tokyo 2020 Olympics.

Another issue is titled アイドル、労働、リップ (aidoru, rōdō, rippu) (Idols, Labor, Lipstick). And this one is about idols. I’m not familiar with the topic, but I’m working with Minori Suzuki, who is nonbinary and writes about gender issues, and Ayaka Wada, who is an idol herself.

EW

I’m curious what other themes you are interested in for the future.

AM

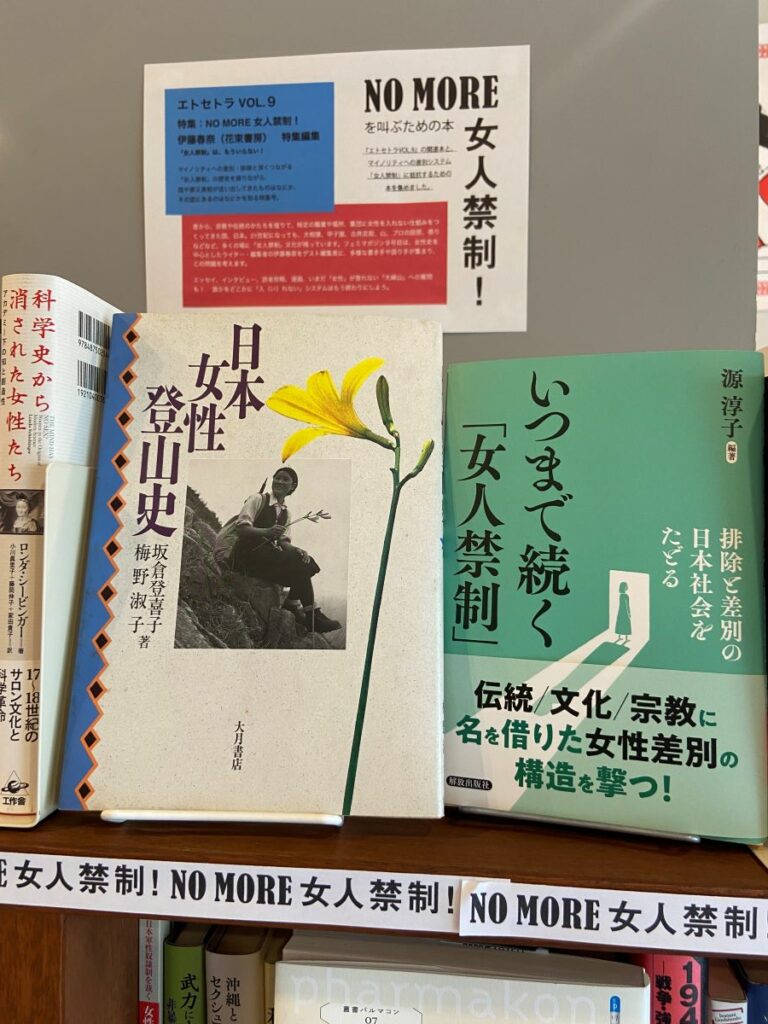

Do you know about 女人禁制 (Nyonin Kinsei) (No Women Admitted)? It is a Buddhist tradition in Japan that forbids women in many places. Even today, there is one mountain in Japan that women cannot climb.

Also, do you know about sumo?

EW

Yeah, women are not allowed either, right?

AM

Nyonin Kinsei continues in many, many places. We are working with Haruna Ito, a female history writer to discuss the many issues around this. And the following issue of etc. is about men’s studies (男性学) (Dansei-gaku).

I used to think that men should just do men’s study among men [laughs], but a trans man asked me to do this issue together, and we went for it.

EW

I can’t wait to read it!

I’m also curious about how the Japanese feminist movement relates to feminism in other countries?

AM

The feminist movement in Korea is the closest to Japan, but their feminism is more advanced, one or two steps ahead of us. We respect each other, and we have solidarity and sisterhood together.

I think we can consider this problem with Korea together because they share the same patriarchal system. However, Japan was a perpetrator of colonial violence against Korea, so I don’t think we are equal. I think it is important to keep Japan’s imperial history in mind even as we build international solidarity with Korea. But at least I think we can think about patriarchy together.

This interview has been edited for clarity. Moeka Sakuma helped transcribe and translate the conversation.