An examination of Malayan Emergency fiction’s depiction of Sinophone, Anglophone, and Indigenous points of view

September 6, 2023

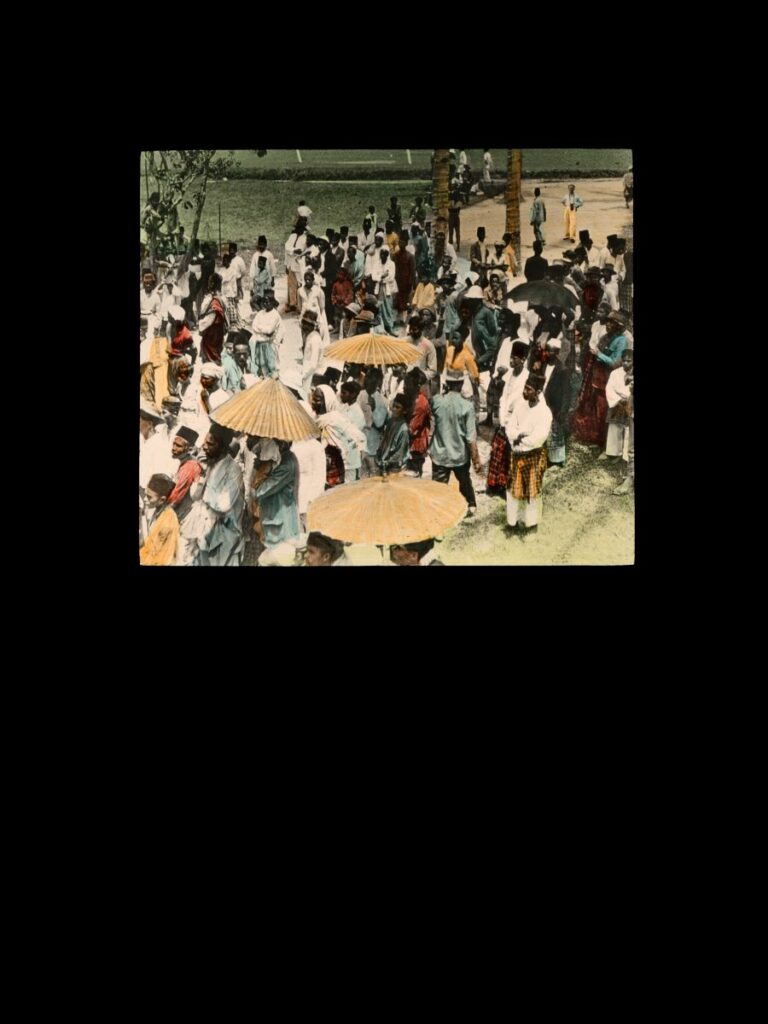

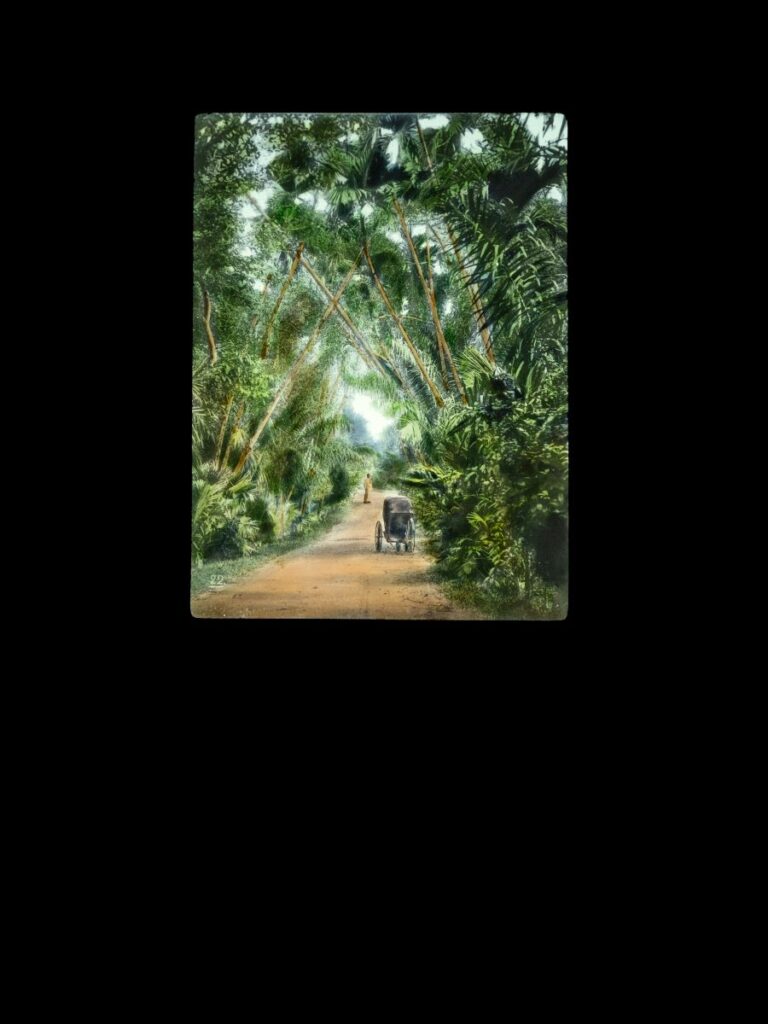

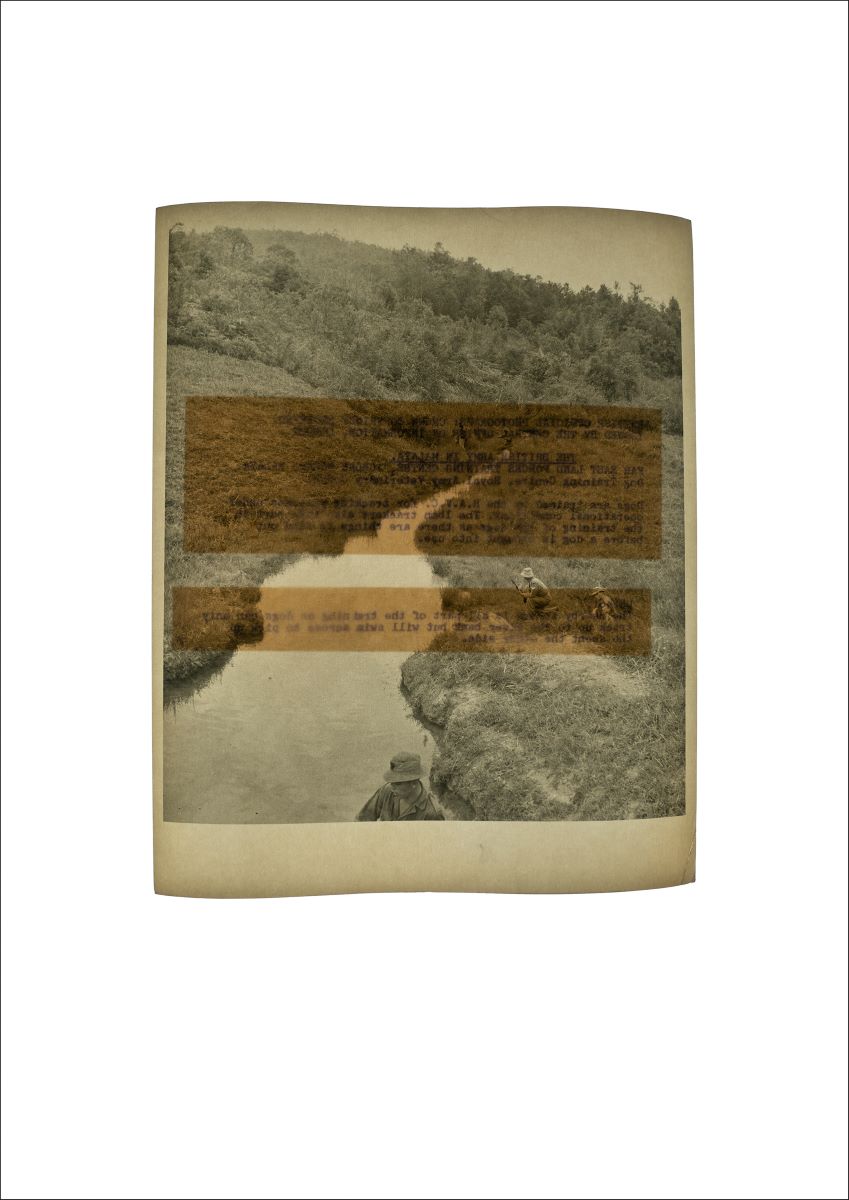

This piece is part of “The Rainforest Speaks: Reimagining the Malayan Emergency,” featuring art by Sim Chi Yin.

In Jeremy Tiang’s novel State of Emergency (2017), Stella, accused of being a Marxist conspirator, says, “I read books,” when an officer asks her how she knew that Singapore’s ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) was socialist until the seventies when they left the Socialist International. Another left-leaning character, Siew Li, says, “She’d read Animal Farm, and knew the main thing in any movement was not to turn into pigs.” Ironically, George Orwell, who published the novel in 1945, was not sympathetic to communists. But Tiang’s characters read for historical and moral clarity, and are not afraid to say so. In fact, by reading Tiang’s novel, we bear witness to acts of historical redress. We follow Revathi the journalist, generations removed, back to Malaysia to report on Batang Kali and interview survivors to press the British government to open a public inquiry into the 1948 village massacre.

Chin Peng’s memoir, My Side of History (2003), names the books that he and others under his leadership read, before and during their time in the jungle. In Tiang’s novel, reading not only brings about revolutionary consciousness, but is also shown as an ex post facto problem of narrating the historical present. A character, Lina, asks Siew Li to read Mao Dun, the left-wing realist Chinese writer who had written Rainbow (1929), a novel about a young woman becoming revolutionary in China. Incidentally, Mao Dun wrote a critical biography of Walter Scott, whose historical novels the Marxist critic Georg Lukács praises for having captured society despite his own class background. Narrating events to reflect individual growth and society’s transformations, or better yet, narrating events from the other’s point of view—radically alien as it may be to one’s interests—can twist the event into a discourse about itself. Such novels call attention to an event having multiple points of view but also the writers’ reasons for hiding or revealing this complexity. For restitution’s sake, whose point of view is preferred?

Being partial, or having a distinct point of view, is often necessary for restitution. Being partial challenges official narratives and their cool, totalizing gaze. Being partial exposes the harrowing effects of counterinsurgency only known from the victims’ eyes. Such is the method of Tiang’s novel: the fragmented telling of several women’s accounts is key for their stories to come together through partial acts of listening and reading. We see this tack in public forms of restitution, such as visualization (art and GIS mapping of New Villages), ethnography (family histories); and lists (bibliographies) about the Malayan Emergency (1948–60)—the colonial government’s term for the armed conflict.1For visualization, see Sim Chi Yin’s photography in this portfolio and “The Malayan Emergency: Digital Map”; for ethnography, see Nnull, “On the 1948–1960 State of Emergency in Colonized Malaya and the Emptiness of my Birth Certificate,” Funambulist 29 “States of Emergency” special issue (2019); for lists, see “The Malayan Emergency: Bibliography.” Emergency fiction like Tiang’s enacts this recognition as silent reading, asking readers to inhabit partial viewpoints.

Restitution in literature can act as rehabilitation or pingfan, which restores the good name of a wrongly maligned person as in the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966–76). Both restitution and rehabilitation can seek justice and a posthumous revision. But in the anglophone Malayan context, rehabilitation involves colonial-national authorities steering communists away from their ideology. Using pamphlets, Malayan communists are asked to surrender in exchange for a generous rehabilitation package that absolves their treason.2See Zhou Hau Liew, “A Story of Permatang Tinggi,” PR&TA 1, “Migrations” (2021). Rehabilitation involves the authorities taking on the other’s point of view to figure out their needs: food, family, shelter, and official protection that the communists lack. If successful, it assimilates the communists to their enemy’s point of view.

Initially, I’d wanted to counterpose sinophone restitution to anglophone rehabilitation as a way to challenge the motif of rehabilitating the communist in English-language historical fiction about the Emergency, and its symptom as postcolonial Malaysian literature. Because Tiang is a translator from Chinese into English, the argument goes that Tiang’s novel, though written in English, introduces sinophone points of view into anglophone forms of reading. Here, Malayan communist subjects are voiced demanding restitution rather than ventriloquized on their way to rehabilitation. Failing which, they are not merely known and prosecuted as communist terrorists (CTs), as Tan Twan Eng’s novel The Garden of Evening Mists (2012) calls them, following Colonial Office documents; Min Yuen (civilian sympathizers) are also deported to China for “supplying food to the terrorists and acting as their courier.” Tan does challenge the stereotype that Malayan communists were all Chinese, though, using the figure of Manap, the Malay-Japanese communist fighter: a nod in the direction of the Malay Tenth Regiment of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM).3See Mohamed Salleh Lamry, “A History of the Tenth Regiment’s Struggles,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 16:1 (2015): 42–55.

To be sure, Tan’s novel, which won the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction in 2013, is partial, but just not to communists.4A far less sympathetic portrait of the communist cause is Anthony Burgess’s The Long Day Wanes: A Malayan Trilogy (1956–59): “The Communists in the jungle subscribed, however remotely, to the Hellenistic tradition: an abstract desideratum and a dialectical technique.” Both intellectual and actual communists for Burgess require neither restitution nor rehabilitation. Burgess intends each point of view during the Emergency to be given equal-opportunity judgment as mockery or farce. It demands anglophone restitution for Japanese war crimes and colonial British injustice against Chinese. In the novel, the retired judge Teoh Yun Ling observes that the British government betrayed Malaya when it waived “all reparation claims of the Allied Powers and their nationals” from the Japan Peace Treaty, making relatives of war victims unable to “demand any form of financial reparation from the Japanese.” Despite critiquing governments, the novel portrays foot soldiers with sympathy—Japanese youths sent to their deaths. Tatsuji’s moving confession as a queer kamikaze pilot in one chapter explodes the wartime rhetoric of collaboration, resistance, and espionage. Intriguingly, Tan brings in the unresolved history of Anglo-Boer relations into the novel to critique empire, reflecting his South African concerns. Magnus Pretorius, a prisoner-of-war who survived the Second Boer War (1899–1902), remembers: “Every morning we were marched to the slopes to work alongside our coolies. But I have to say, the Japs were kinder to us than the English were to my people.”

Like Tiang, Tan’s focus on British injustice comes in the wake of the declassification of colonial British archives, which produced high-profile court cases directly related to British violence during the Emergency years in Malaya.5Similarly, Mau Mau detainees built their case against British war crimes committed in Kenya based on Caroline Elkins’s book, Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya (2005). Yet the two novels present restitution in the post-war Emergency years differently. Whereas Tan views this era as a sequel to the Japanese Occupation (1942–45)—where Malayan communists play minor roles in competitive claims of national injury—Tiang views this era as the prequel to Singapore’s state crackdown of what was called the Marxist conspiracy of 1987, as experienced by the character Stella.

Hence the theme of sinophone restitution versus anglophone rehabilitation would merely rehash Emergency distinctions of right and wrong, nationalist and communist, Malay and Chinese, English- and Chinese-educated, friend and enemy, loyal soldier and double agent, colonial triumph and decolonial failure. What’s common is writers’ attraction to depicting the Emergency from the viewpoint of others, political friends and enemies alike. Such acts of empathy, of burrowing into the brain of someone so different in terms of ideology, class, and race to consider their ideas, also shatter the coherence of their own mentalité. These often take the form of stand-alone chapters, stylistically and temporally cut off from the novels’ main thrust. Like the confessional narrative of Tan’s kamikaze pilot, such restitution, however briefly, of the other’s point of view is shocking enough to destabilize the novel’s hitherto point of view.

In Han Suyin’s novel, … And the Rain My Drink (1956), the chapter called “The People Inside” is a diary presented from a first-person communist point of view. Written during the Emergency, Han Suyin writes with sympathy about female communist guerrillas who have surrendered and are being rehabilitated, but are still considered as traitors. Although they are now informants for the British, there is nagging suspicion that they are double agents; did they not just betray the communist cause? Han Suyin’s ethical stance results from her experience of witnessing colonial British counterinsurgency techniques as a medical officer stationed in Johor Bahru, Malaya after 1952. She became a loyal supporter of Mao Zedong and communist China. Her husband, Leon Comber, supposedly resigned from his position in the Police Special Branch because of the backlash that resulted from her novel’s anti-British, pro-Left sentiments. Han set the terms for restitution even before the Emergency ended, before Malayan communist writings in Chinese were rediscovered in the 1990s, by staging an uncertain communist rehabilitation.

Another pro-Left work deriving from the Emergency is Scattered Bones (Tulang-tulang Berserakan, translated from Malay by Hasnah Ibrahim in 2009), the only novel by the Malay journalist and writer Usman Awang, who was stationed at the fringes of the jungle as a Police Guard for the British in Malacca (1946–51) to fight the communists.6See also Kirk Endicott and Robert Knox Denton, “Ethnocide Malaysian Style: Turning Aborigines into Malays.” “Field assistants—mostly Malays with some police or military experience—were posted at the jungle forts. They took responsibility for medical care, and some offered informal classes in reading and writing Malay to Orang Asli children.” Completed in 1962 and published in 1966—in the post-independence era—this anti-colonial novel envisions pan-Indonesian unity, and uses the earlier conflict of the Emergency to comment on Konfrontasi, Indonesia’s opposition to the creation of Malaysia in 1963. Like Han Suyin, Usman includes a single passage in which the protagonist Leman’s point of view suddenly shifts to that of a Malayan communist fighter.7Usman Awang, Scattered Bones, translated by Hasnah Ibrahim (Kuala Lumpur: Institut Terjemahan Negara Malaysia & UA Enterprises, 2009), 216 and 233. Charting the protagonist’s growth as a writer, the novel resolves Leman’s complicity with violent colonial rule not by rehabilitating treacherous viewpoints in the road toward independence, but by addressing the struggle of common men drawn into conflict by British interests; hence, a ‘universal humanism’ that excuses the main character’s “going into the jungle, hunting people he never knew.”

Usman’s affiliation was to the leftist Malay Nationalist Party of Malaya (PKMM), a pro-communist and anti-UMNO party known for its establishment of Pusat Tenaga Rakyat (PUTERA), a coalition of radical Malay Left parties which then merged with the All-Malaya Council of Joint Action (AMCJA) to oppose the 1948 Federation of Malaya agreement.8For details on Indonesia Raya, PKMM, the Tenth Regiment, see Souchou Yao, “Chapter 7: On the Malayan Left: The CPM and the ‘National Question’,” The Malayan Emergency: Essays on a Small, Distant War (Copenhagen: Denmark:Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Press, 2016), 116–33. The PKMM sought a pan-Indonesian unity of the Malay peoples (while maintaining friendly relations with other races), and this is reflected in the novel’s sympathetic account of innocent Chinese characters, the Malay schoolteacher Alimin, and Indonesian nationalist Anuar. Usman’s appeal for restitution is not partial to communists, but embodies the leftist Malayan project from a Malay point of view, whereas Tiang is partial to Singapore’s anglophone and sinophone left.

Decades after Usman and Han published their sympathetic accounts, CPM fighters who destroyed their arms after the Peace Agreement of Hat Yai (1989) started publishing their own versions of sinophone restitution via memoirs, oral narratives, and reportage about guerrilla warfare during the Emergency—also known as Magong writing (Magong shuxie).9Ng Kim Chew (Huang Jinshu), among others, have drawn on this archive to write “Magong” fiction. For Ng, sinophone restitution for Malayan communism cannot be found in card-carrying Magong writing from the jungle, but ironically in its rehabilitation for a broader Mahua reading public to assess its significance. Jin Zhimang transcribed the accounts of fighters in CPM’s armed wing, the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), into a collected volume called Ten Years (Shinian), which he parlayed into his more well-known work, the novel Hunger (written 1958, published 1960, allegedly revised by others in China in the 1970s, rediscovered in the 1990s).10Jin Zhimang’s Hunger was originally published under the pen name Xia Yang, Ji Binzhou bei xingshe 吉槟州北星社, 1960. In 2001, Hong Kong’s Nandao chubanshe 南島出版社 commissioned its republication. Hunger charts the claustrophobic tale of survival and ultimate failure of the Malayan communists in social realist mode. There’s an unexplored aspect of Jin’s writing: sinophone rehabilitation of native interests to the communist point of view, presented as aboriginal solidarity for the communist cause.

Writing from the indigenous point of view does not amount to representation nor does it cover indigenous interests. But because Chinese—herded off to heavily surveilled zones called New Villages—and orang asal alike faced resettlement and territorial dispossession, Jin Zhimang, known in the CPM as a “people’s writer,” found common ground to argue against the racialization of indigenous peoples and Chinese who were resettled from the frontier. Before restitution became a historical problem, it was primarily a revolutionary task for Magong to inhabit the other’s point of view so as to deliver genuine communism and have broad appeal. Jin articulated class interests across ethnic boundaries in a few novellas in order to bid for support, putting him in conflict with planters, miners, exporters, and industrialists. Having argued on behalf of the Malayan “here and now” (cishi cidi) in the 1947 sojourner-local literary debates, with the Chinese civil war (1927–49) dividing Malayan Chinese writers’ attention, Jin put his word to the test after he left towns for the jungle in 1948.

The jungle-based MNLA regiments came into frequent contact with indigenous orang asal and Malay villagers, and relied on them for food and information when it was risky to reach the Min Yuen sequestered in New Villages. Jin’s narratives thus portrayed solid anti-colonial rapport between the MNLA and orang asal. Both the colonists and the communists competed for the allegiance of orang asal, such as the Senoi, comprising the Semai and the Temiar tribes, who knew the jungle terrain well. In 1956, under Colonel Richard Noone’s direction, the British Malayan Security Forces organized the orang asal as the Senoi Praaq (War People or orang perang) to fight against the communists in remote areas. Noone, a Military Intelligence officer who became “Protector of Aborigines” in 1953, had gone looking for his missing brother, the Cambridge-trained anthropologist H. D. “Pat” Noone, a previous holder of the title in Perak. Jin’s restitution of communist histories challenges colonial-national depictions of orang asal involvement in the Emergency.

Malayan Communist propaganda plays are valuable as sources of restitution now, but back then considering the other’s point of view helped the CPM counter the intense rehabilitative psychological warfare waged by the colonial state. The revolutionary play, Pengheng he er nü (Children of the Pahang River), published by the Malayan Liberation Press (Malaiya Jiefang she) on June 20, 1968, was first performed in 1967 by the 10th Regiment in Malay, and subsequently in both Chinese and Malay in 1968 and 1978 to commemorate the CPM’s 20th– and 30th– anniversary of the struggle. Recorded in bilingual editions for broadcast on Suara Revolusi Malaya in 1979, the play extolled the CPM’s leadership in the Malay agricultural movement.11“Ma Tai bianqu fengyun lu—guangrong jianju de renwu 马泰边区风云录: 光荣艰巨的任务 [Records of the Struggle at the Malayan-Thai Border: A Glorious and Difficult Duty], ed. Fang Shan 方山 (Kuala Lumpur: 21 shiji chubanshe), 2005–2007, vol. 3, 283. Their use of plain speech and naïve sincerity, overlaid with sarcasm and light-hearted humor, was more effective than the colonial British’s flawed, simplistic strategy of “winning hearts and minds.”12Rachel Leow, Taming Babel: Language in the Making of Malaysia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 161–70.

On closer look, Magong writing depicts the Emergency from the other’s point of view and substitutes solipsism with broader claims for restitution. Jin Zhimang wrote his first novella, Datuk Yang Yang and His Village (Du Yangyang he ta de buluo), from the point of view of an orang asal leader, Du Yangyang, who tries to resist, but succumbs to, a traitor’s attempt to convince them to move from the Perak jungle into a New Village, or concentration camp (jizhong ying) in 1952.13Jin Zhimang, Renmin wenxue jia Jin Zhimang <Kang Ying zhanzheng xiaoshuo xuan> [The People’s Writer Jin Zhimang’s Stories on the Anti-British War] (Kuala Lumpur: 21 shiji chuban she, 2004), 17–75. Also, see Shinian: kang Ying zhandou gushi ji (shisi ji) [Ten Years: a Collection of Stories on the Anti-British War (14 volumes)], ed. Jin Zhimang (Kuala Lumpur, 21 shiji chubanshe, 2013), vol. 2, part 5 (Huoju chuban she, 1954). The story ends with the fates of the communists (called langwai, or “youth from outside”) and orang asal bound together against the colonists. Heroically, the langwai avenged the orang asal, saved them from the camp, and brought them back to the jungle. For Datuk Yang Yang, “the langwai fight, while orang asal show the way, deliver food, spy, and grow bananas.” The MNLA organizer of orang asal, Lao Jiang, justifies their mutual dependence: “the langwai and orang asal live in the jungle together, just like fish in water.”14Jin Zhimang, The People’s Writer, 68–69. For a synopsis of this novella, see Nicholas Y. H. Wong, “Minor-Peninsular Genres: Genealogies of Twentieth-Century Southeast Asian Chinese Writing,” PhD dissertation, University of Chicago (2019), 165–68. Parts of this essay were adapted from “Chapter 3: Jin Zhimang’s Malayan Communist Realism, Collective Writing, and the Construction of National Culture.” Mao Zedong, in his 1937 essay “On Guerrilla Warfare (Lun youji zhan),” likened the relationship between troops and the people to fish in water. Jin’s indigenous leader heroically embraces communist leadership, who shatters the coherence of his mentalité—no surprises here.

Jin Zhimang wrote a variation of this story, called “The orang asal and the langwai (Ahsha he langwai),” using different narrative forms to give shape to real-life events.15Ten Years vol. 6, 33. In fact, the character of Lao Jiang was likely based on a “small businessman from the Merapoh area (Perak, near the border with Kelantan),” who “joined the Malayan National Liberation Army in 1949 and was reputedly the most effective CPM organizer of orang asal in the surrounding region. His real name was How Chu Su.”16Footnote 1 in John D. Leary, “The Malayan Communist Party and the Asal (Orang Asli).” Magong fiction does not merely document guerrilla experience from their point of view, but acts as restitution for actual personnel names, genealogies, and organizational structures.

Another novella of Jin’s, Kampung Belum (Ganbang Hulong) recounts an idyllic life in a Malay village.17Wu Liang, Ten Years, 206. “Kampung Belum” is compiled in Ten Years vol. 9 (Huoju chuban she, 1960), and is attributed to Jin’s pen name Yong Ding. The MNLA and the masses solidify their relationship in a fish-catching scene. Wu Tien Wang translated “Kampung Belum,” this cheery tale of solidarity and resistance, along with Mao Zedong’s “The Battle at Jinggang shan (Jinggang shan de douzheng)” and “Village Survey (Nongcun diaocha)” into Malay.18“Wu Tianwang tongzhi jianli” 伍天旺同志简历 [A Brief Biography of Comrade Wu Tien Wang]. In 1947, Wu was among the three CPM delegates, together with Rashid Maidin and the Perak trade unionist R. G. Balan, who attended the British Empires Conference of Communist Parties in London.19Christopher Bayly and Tim Harper, Forgotten Wars: Freedom and Revolution in Southeast Asia (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007), 343. Such a restitution of communist names and histories becomes tricky when Magong members wrote under numerous pen names, either to evade capture, advance collective authorship, or attribute their literary beliefs to past heroic deeds and actions.

Just like Emergency fiction, Magong writing uses the other’s point of view to advance its idea of restitution, but this can seem like rehabilitation of indigenous perspectives as communist. But had Magong fiction and memoirs not survived, we would not know that communist restitution involves guerrilla warfare, jungle life, solidarity claims, and collective writing. Magong writing also shows how complex restitution can be from within the viewpoint that Emergency fiction later restitutes. While fighting a war, the CPM cherishes victory, which does not need restitution. Only when the CPM lost, or knew it was losing, did literary acts of restitution become urgent. Even as a record of failure, Magong writing wanted to show that at one point, the CPM had orang asal and Malay farmers on their side. In Emergency fiction and Magong writing alike, the fulcrum of restitution is the other’s point of view.