لكن المنـفى ينبت مرة أخرى كالحشائـش البرية تحت ظلال الزيتـون | Exile sprouts anew, like untamed grass beneath the shade of olive trees

one leftover lychee from last night’s mimosaing, mimosaed decadence

A young woman struggles to stay in a loving relationship while being haunted by a past abuser.

You lived in this body and

ripped the wallpaper out.

I had loved, fathered, and given up

on my dreams in this otherness

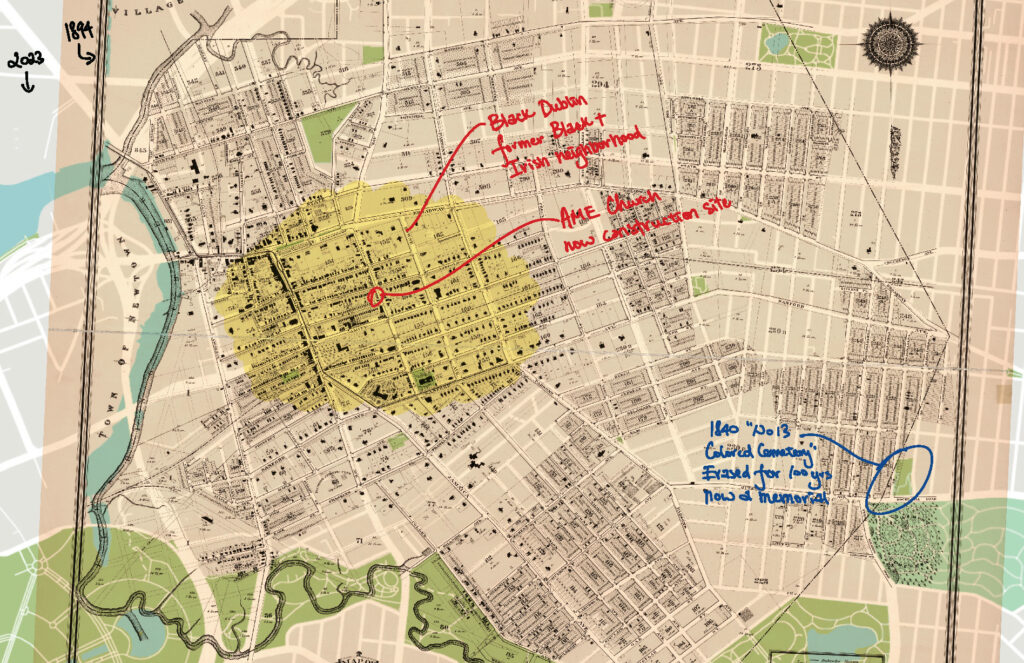

The layered histories of Black and Asian communities in the Queens neighborhood.

Translating Anuradha Sarma Pujari’s My Poems Are Not for Your Ad Campaign

If you play, you wish to be innocent. If you do not, you submit to empires.

before she could contemplate doing something for herself with her time

Once a Maoist dry-goods business, the store has become a hub for Asian American culture and community

She makes the most beautiful cakes with her hands, my mother. They’re never too sweet.

If you play, you wish to be innocent. If you do not, you submit to empires.

one leftover lychee from last night’s mimosaing, mimosaed decadence

A young woman struggles to stay in a loving relationship while being haunted by a past abuser.

before she could contemplate doing something for herself with her time

You lived in this body and

ripped the wallpaper out.

Once a Maoist dry-goods business, the store has become a hub for Asian American culture and community

I had loved, fathered, and given up

on my dreams in this otherness

The layered histories of Black and Asian communities in the Queens neighborhood.

She makes the most beautiful cakes with her hands, my mother. They’re never too sweet.

Translating Anuradha Sarma Pujari’s My Poems Are Not for Your Ad Campaign