In 1999, Fred Ho reflected on his political and musical evolution, from the Asian American Movement on.

May 19, 2014

This essay is part of a Counterculturalists installment commissioned by AAWW to honor the life and legacy of Fred Ho, the radical composer and organizer who passed away in April 2014 after an eight-year battle with cancer. See our introductory post for a full list of contributions.

The full version of this essay was originally published in Leonardo Music Journal, Vol. 7, 1999.

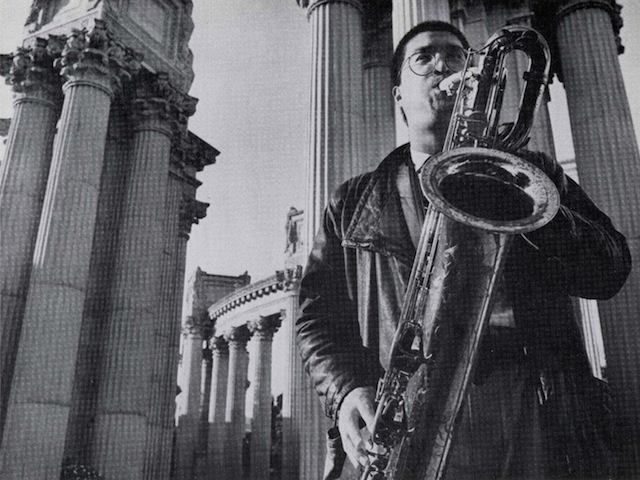

At the age of 14, I acquired a second-hand baritone saxophone from my public school band and began seriously to investigate African American music, especially its more radical and “avant-garde” forms, the so-called Free Music of the 1960s. I searched for a creative expression that would give voice to my exploding radicalism, my hatred of oppression and my burning commitment to revolutionary struggle.

It was the music of little-known composer Calvin Massey in particular (as performed and recorded by Archie Shepp) that had a major impact on me. Massey’s extended suites, such as “The Black Liberation Movement Suite” (which he wrote for fundraising concerts for the Black Panther party), strongly appealed to me, with their thematically epic historical scope, Fanonic titles (e.g., “The Damned Don’t Cry”), soulful melodies, complex and rich harmonies, Afrocentric rhythms (i.e., more African-inspired or African American interpreted than actually traditional African). It was the music of liberation and revolution (connected to the “jazz tradition,” simultaneously swinging and radical); one could hear the Black Panthers marching inside the music itself.

My cultural awakening and entrance into revolutionary politics occurred in the mid-1970s. The lessons I drew from my study and involvement in “jazz” about the role of art and music in revolutionary social transformation extended far beyond the simple expression of political views through song lyrics or titles and their subsequent use in social movements, which has comprised the primary discourse about music and social change. Rather, I saw the politics of music in musical aesthetics, in ways of music-making and in building alternatives to the music industry.

During this time, I joined an Asian American counterpart to the Black Panthers, I Wor Kuen (IWK). By the mid-1970s, most Asian American revolutionaries had become Marxist-Leninist (M-L) and belonged to one of several national M-L organizations: I Wor Kuen/League of Revolutionary Struggle (LRS), Workers Viewpoint Organization/Communist Workers Party, Wei Min She/Revolutionary Communist Party, Katipunan Demokratik Pilipino/Line of March, etc..

I was one of the younger activists of that generation. Much of the sociopolitical and cultural advances in today’s Asian Pacific American (APA) communities—social services and legal aid programs, Asian American Studies and art/cultural organizations—were products of struggles waged by APA revolutionaries and militants of this period. Many communists and revolutionaries initiated and founded organizations (albeit presently devoid of their original militancy) such as Visual Communications, Japantown Art and Media, Kearny Street Workshop and Asian Cinevision. Other APA cultural organizations that have since ceased operations include Community Asian American Mural Project (CAAMP) in Oakland/Bay Area, Bridge Magazine, East Wind Magazine, Basement Workshop, Ating Tao, Kalayan, and Dragon Thunder Arts Forum. APA communists were even members of many Japanese American taiko (drum) groups on both coasts, which tended to attract ex-activists and ex-communists who wanted taiko to be “cultural” or apolitical as they were both burned out from and negative towards radical activism.

Being from a middle class intellectual background, belonging to IWK/LRS reoriented me towards the proletariat or working class. I did my political work as a cultural organizer in Boston ’s Chinatown, an immigrant and working class community. Fresh out of college activism, I agreed to my political assignment to organize the Asian American Resource Workshop (AARW), a fledgling educational and cultural group in the community. In the AARW, we started the first Asian American poetry readings in the community, organized a bi-weekly and monthly summer coffee house series that featured agit-prop theater (“skits”) in both Chinese and English, and other bilingual cultural performances. I and other IWK/LRS cadres led the AARW as a vehicle to unite both American-born, English-speaking Asian Americans and Chinese immigrant working class youth and adults. As co-leader of the AARW Chinese folksinging ensemble, I began to learn and draw inspiration from the rich heritage of Chinese folk songs.

Guided by this general political direction, I embarked upon a serious and extensive research into the folk traditions and roots of Asian American culture. It became clear to me that a working class, even revolutionary tradition exists in APA cultures. Such a tradition includes the first immigrant cultural forms: Cantonese opera, the woodfishhead chants, the talk-story traditions, the folk ballads and syllabic verses of the Chinese immigrant laborers, the Japanese American female plantation labor songs (hole hole bushi), the Angel Island poetry, the Filipino randalia and folk ballads of the manongs (Filipino immigrant bachelor workers), Japanese American tanka (syllabic verse) poetry.

It also became evident to me that a huge gulf has existed between this rich traditional heritage of immigrants and the highly Western-imitative cultural expressions of the American-born. In the late-1970s, IWK put forward a published position that Asian American art and culture necessitates a link to traditional Asian cultural forms. During this time, the APA movement was attempting to address the question of what makes Asian American art/cultural expression Asian American?

By and large, these attempts at a revolutionary theory of APA art and culture simply reiterated standard M-L views (mostly from Mao’s Yenan talks on art, literature, and revolution) on the political and class nature of art, the propaganda value of folk and popular forms, the question of aesthetic form and its dialectical, yet subordinate, relationship to revolutionary proletarian content. This theoretical shallowness was reflected in an equally shallow early Asian American Movement music—a derivative of either white folk and leftist styles a là Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger or African American gospel, soul, and rhythm and blues idioms. The major limitation of the American Left’s theory and practice in cultural work has stemmed from the influence of socialist-realism (the Zhdanov policies of the Soviet Union), commonly regarded as “agit-prop.” This theory regards art solely for its utilitarian value as a vehicle for propaganda. With the advancement of both my professional artistic career and my personal understanding of the complex relationship between ideology, the arts, and struggle would come frustrating and conflictual struggles with the LRS political leadership around these issues, including the validity of “Asian American jazz.”

“Asian American Jazz”: 1982-1989

Self-ascribed “Asian American jazz” emerged during the periods of the late 1970s-early 1980s, primarily from a small group of Bay Area West Coast musicians. These “Asian American jazz” musicians included saxophonist Russell Baba, bassist Mark Izu, bass clarinetist Paul Yamasaki, and New York violinist Jason Hwang, among others, including myself.

This grouping represented some of the more imaginative contemporary efforts towards forging a distinctive Asian American Music. These instrumentalists and composers combined actual Asian traditional instrumentation and Asian-inspired or influenced stylistic elements with predominantly “free” or modal improvisation in the African American avant-garde “jazz” context. Indeed, much of their music had more to do with the developments within the 1960s African American “jazz” avant-garde of Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Archie Shepp and others than a substantial cultural grounding within traditional Asian music. However, the identification with the musical radicalism of the 1960s often reflected a concomitant ideological radicalism. Clearly, we were aligned with the most militant of the African American improvised music of the 1960s.

During the 1980s, I emerged as one of the leading “Asian American jazz” artists on both coasts. I was constantly writing reviews and (often polemical) essays that argued for an Asian American culture and artistic expression rooted to immigrant and working class traditions. I sought to clarify—for other Asian American artists and for my own artistic creation—a revolutionary Asian American art/music that embraces tradition and change and that would not be imitative of Eurocentric and white pop forms but innovative by inheriting and expanding upon the continuum of Asian Pacific American cultures.

Beyond rejecting “art for art’s sake,” I polemicized against the white assimilationist notion of the petty bourgeois Asian American artist that anything by an Asian American artist makes it Asian American. While also rejective of being proscriptive or essentialist, I do maintain that the Asian American-ness of an artistic work lies in more than content, and is rooted and linked to cultural traditions and forms. Along with expressing aspects of the “Asian American experience,” the music itself would draw from or reflect aspects of traditional Asian music influences. Yo-Yo Ma is a cellist who happens to be Chinese and Asian American, not a Chinese / Asian American musician. John Kaizan Neptune is a white American virtuosic shakuhachi (traditional Japanese vertical flute) player, but he is not playing Japanese / Asian American music because he is not intending to express or reflect a Japanese / Asian American identity. While Asian American music may very well be cross-cultural, we in the “Asian American jazz” movement saw as the focus of our music and cultural work to help catalyze Asian American consciousness about our oppression and need to struggle for liberation. The very identity and term “Asian American” in our sobriquet “Asian American jazz or music” is a political signifier.

By the late 1980s, I was musically and ideologically evolving away from “Asian American jazz.” (And as further discussed below, I was also moving away from the growing political rightism of the LRS, reflected in its “line” on cultural work of producing work that would be “accessible”—in my view, tailing the familiar and conventional.) As “Asian American jazz,” my first four recordings as a leader of my Afro Asian Music Ensemble and now-defunct Asian American Art Ensemble featured compositions that spoke to the Asian American struggle and celebrated the resistance of Asian workers in the U.S. I also consciously collaborated with and brought together other progressive Asian American artists and featured them in my performances and recordings, including poets Genny Lim and Janice Mirikitani, musicians Francis Wong and Jon Jang (the one artist featured on all of my first four recordings), San Francisco Kulintang Arts, and visual artists Yong Soon Min, Santiago Bose and others doing album cover art. An “Asian American jazz movement”—coalesced via the Asian Improv Records (AIR) label initiated by Jang and including myself, Wong, Glenn Horiuchi, and other then-LRS cadres—was beginning to bloom. However, in the late 1980s, both musical / aesthetical and political changes would result in differences that would later lead me to break from AIR (with whom I had been recording) and then eventually with the LRS.

Afro Asian New American Multicultural Music: 1989-Present

Heretofore, I would characterize my music as “jazz” with Asian American thematic and musical references. But 1986 was a major aesthetical turning point for me. I was continuously struggling with the question of what makes Chinese American music Chinese American? What would comprise an Asian American musical content and form that could transform American music in general rather than simply be subsumed in one or another American musical genre such as “jazz”?

I began to embark upon a course that I articulated as creating “an Afro Asian new American multicultural music.” Taking Mark Izu’s significant leadership in the incorporation of traditional Asian instrumentation (in his case, mostly in improvised or incidental approaches), I began to explore such an incorporation in a composed, orchestrated manner. With no desire to be a Sinophile or traditional Asian music academic, yet recognizing the importance of studying and drawing from traditional formic structures, I wanted to evoke the spirit of folk music in both solo and ensemble performance and in composition.

As early as 1985, in my multimedia work Bound Feet (led by then-Asian American Art Ensemble member, actress, and vocalist Jodi Long), I incorporated the Chinese double reed sona and the Chinese two-stringed vertical violin, erhu, with Western woodwinds, contrebasse and multiple percussion. I wrote the sona and erhu parts in Chinese notation, an ability I had acquired from the days leading the Boston AARW’s Chinese folk-singing group during the late 1970s-early 1980s. In Bound Feet I became excited about the musical results of this embryonic integration of Eastern non-tempered and Western tempered instruments. While employing my own “jazz” voicing in the harmonization of the parts, I had struck upon some new, fresh, and unusual timbral qualities from this combination. This synthesis of Chinese and African American components seemed to be a musical analogy for the Chinese American identity or, even further, something Afro Asian in sensibility.

In 1986 and 1987, I embarked upon composing what was to become the first modern Chinese American opera, A Chinaman’s Chance. I wanted this new opera to be an extension of the traditional Chinese opera in America that was once so flourishing in the Chinatown communities before World War Two. My concept was to utilize the woodfishhead and syllabic verse chants as episodic narration. Less of a conventional story than a historical suite, A Chinaman’s Chance is about the transformation of the Chinese immigrant god, Kwan Gung, as metaphor for the transformation of the Chinese to becoming Chinese American. In April 1989, a one-time stage production was presented at the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Majestic Theatre. I consider this first opera of mine to be an experimentation for me in working out an extended Chinese American music-theatre form, and was satisfied with neither the work as a whole nor its staging. Out of this first effort, I became committed to putting the music ensemble on stage as part of the theatrical setting rather than buried in a subterranean orchestra pit. In future staged music-theatre and opera productions, I plan for the music ensemble to be elevated 10 feet off stage in the air, to be part of the “heavens.”

New lessons and new directions flowed from these experiments in my efforts to create a true multicultural synthesis. The integration of two vastly different musical traditions requires bi- or multicultural musicians and artists willing to stretch beyond their traditional roles and musical understanding. As such, experimental works sorely lack financial resources, and it is hard to sustain the years of rehearsal and interfacing needed to forge such an interactive musical dialogue and exchange. The process of forging my multicultural music has taken many years of efforts through such projects, working with a stable core of musicians who have come to understand (albeit unevenly) the concept towards which I am striving.

The Chinese artists with whom I work are not only master musicians within their own traditions and contexts, but are also open to playing my music, which they call “jen chi gwai” (literally, “very strange”). Their initial skepticism toward combining Chinese and “jazz” music has since given way to genuine excitement and commitment.

I wanted my compositional process to be a real synthesis, and not a pastiche or juxtaposition of contrasting cultural styles. Most “world beat” or intercultural collaborative efforts, in my view, are limited in the extent to which they manifest real and truly “new” synthesis. These efforts are, at best, exoticism when proffered by culturally imperialistic whites and “chop-sueyism” when presented superficially by people of color.

In opposing cultural imperialism, a genuine multicultural synthesis embodies revolutionary internationalism in music: rather than co-opting different cultures, musicians and composers achieve revolutionary transformation predicated upon anti-imperialism in terms of both musical respect and integrity as well as a practical political and economic commitment to equality between peoples.

Nineteen eighty-nine was a watershed year. Artistically, I was moving away from “Asian American jazz” toward “Afro Asian new American multicultural music.” Politically, I had become increasingly alienated from the rightist, reformist decline of the LRS. In the spring of 1989, a majority of its leadership moved to “question” Marxism, socialism and revolution and soon split into a reformist majority and a socialist minority. Interestingly (and what requires further analysis and explanation), the overwhelming majority of Asians in the LRS went along with the rightist liquidation of revolutionary influence. This included the Asian American jazz cadres with whom I had worked closely for years to build AIR and an Asian American jazz movement. After I was ejected in July 1989 for challenging the unprincipled and opportunist liquidation, by the mid-1990s the majority of the LRS had jettisoned socialism, Marxism, and revolution, opting to become Democratic Party hacks and brokers and changing the name of the organization to the Unity Organizing Committee (which soon quickly faded away).

Part of the rightism of this period of the LRS involved a political directive that required music and art to be “accessible” (which became a codeword for culturally mainstream and politically reformist). In internal gatherings, I rose to challenge this position as tailist (obsequious to mainstream acceptance) and accommodationist. As revolutionaries, I argued, the goal of our work must be the raising of both consciousness and cultural and artistic levels and standards, as well as the popularization of innovative, oppositional, transgressive, radical work.

The LRS split turned into a good thing for me, though it politically was a major setback to the U.S. Left and a personal loss since the organization was my life for over a decade. By challenging the liquidationism, I not only reaffirmed my understanding of and commitment to Marxism, but also struggled to move forward, correct errors, discard old baggage, and seek unity with other leftist movements.

Realizing that I may never be signed to a major label or become the celebrity darling of establishment curators and gatekeepers, or even be signed to high-powered management or agents, I knew that I would continue to be primarily a self-producing artist trying to forge alternatives to the corporate or nonprofit institutions via guerrilla cultural production and distribution approaches. As the LRS had self-destructed and the sufficient unity needed for me to join another Left group did not seem to exist, I developed an individual strategy of maintaining independence while making short-term incursions into the mainstream and spending mostly my own personal earnings to fund productions. The challenge to unite my career and revolutionary cultural work requires the same skills and qualities needed to build revolutionary organization: commitment, clarity, creativity and competence. Musically, I disassociated myself with the rest of “Asian American jazz.”

Upon my severance from LRS, in the fall of 1989, I was commissioned by the late Jack Chen, then-octogenarian president of the Bay Area-based Pear Garden in the West, to compose the music for an episode extracted from the Chinese serial adventure classic, Journey to the West. This project began my formation of The Monkey Orchestra, a unique chamber ensemble combining traditional Chinese and Western “jazz” instrumentation and a Chinese language vocalist. It also motivated me to develop my new music/theater, opera and ballet forms. In its premiere as a 25-minute “pilot” episode, “Monkey Meets the Spider-Spirit Vampires” not only became the first Chinese American opera-ballet with a libretto sung totally in Mandarin Chinese, but, more significantly, created a music score that was a unique and unusual hybrid of Chinese and “jazz” music. Throughout the early 1990s, catalyzed by this episodic piece, I incorporated additional episodes that became a four-act, serial action-adventure music/theater piece (or opera martial arts/dance ballet), Journey Beyond the West: The New Adventures of Monkey. Two acts of Journey were eventually fully staged and the first act presented in concert version during the 1997 Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival.

Big Red Media – Revolutionary New American Opera, Musical Theater Epics and Chinese American Marital Arts Ballets: 1997-Present

While I identify with the “jazz” tradition, much of “jazz” has become occupied by reactionaries and their socio-cultural domination of the art, not only as gatekeepers of establishment cultural citadels, but also of prescribed ideology and style. For the first time in the music’s history, twenty-something musicians are stuck playing a style that pre-dates their birth. Others have characterized this current period as “business-suited” music, “neo-conservative,” “retrograde,” etc. I stopped playing nightclubs in the U.S. in 1987 to extricate myself from a carcinogenic environment and a cycle of exploitation. Some people do not view me as a part of “jazz” anymore: to be honest, if what they consider “jazz” is not innovative, radical, or inclusive, that is true. But I believe that the tradition is embodied in all of my works, many of which extend far beyond what the “jazz” herd is doing.

I have composed and am mounting a martial arts ballet (Once Upon a Time in Chinese America . . . A Martial Arts/Music/ Theatre Epic) (Figs 1 and 2), a multimedia Black Panther ballet (All Power to the People!), a trickster/music theatre epic (Journey Beyond the West: The New Adventures of Monkey) and a matriarchalist opera (Warrior Sisters). I lead one of the most unique “jazz” chamber orchestras, the Monkey Orchestra, a 12-piece big band of Chinese and Western instruments with vocals in Chinese. I have had to become a self-producing artist because of my unusual and radical musical, artistic, theatrical, and political vision, which cannot “fit” into conventional producing and presenting modes as they are presently configured. Fortunately, my political organizing skills have helped me as a producer-artist. But more than that, the movement’s politics have informed and developed my own unique musical identity, voice and vision.

The ultimate goal of revolutionary cultural work is to control our means of cultural production so that we do not have to appease funders nor compromise our integrity and principles to the corporate music industry or establishment arts institutions. In the absence of a revolutionary national organization or movement, I have finally been able to form my own production company, Big Red Media, Inc. (BRM). It is not a collective as it might have been two decades ago because I have frankly not found sufficient ideological and political unity with enough professional artists to make feasible the combination of collective decision-making and shared economic risk venture. BRM is what I call a “guerrilla enterprise,” of which I am the sole owner, although I employ and collaborate with many artists on the creation and presentation of my work, and with “consultants” who help support the business operations. BRM’s mission is to produce revolutionary performances, recordings, publications, videos and digital media. In its start-up phase, BRM primarily focuses on my work.

I have not begun to develop a strategy for alternative radical distribution, which will be key to busting the hegemony of the corporate media octopus. In many ways, such a distribution system will require the building of nationwide and international organization and networks that I as an artist can not primarily do. I am always seeking skilled and radical organizers, but due to the general weakness of radicalism today, it is hard to expect people to devote their lives to such an enterprise with near-zero resources.

I still sell my recordings person-to-person at performances as I sold newspapers and publications when I was in a leftist organization. Revolutionary ideological boldness and political activism continue to be essential to me, although figuring out how to survive and progress in a period when the Movement is weak poses continual challenges. I have tried to sum up some of my key experiences in revolutionary cultural work. Hopefully this discussion and analysis of my musical/political development offers lessons and clarity to both the struggle to create revolutionary art and to change the relations of cultural production, all of which, I have tried to argue, is shaped by and shapes the Movement.

MORE IN THE COUNTERCULTURALISTS TRIBUTE TO FRED HO:

Kanya D’Almeida, “To Walk the Gauntlet of Fire: Remembering A Mentor”

Fred Ho, “From Banana to Third World Marxist”

Marie Incontrera, “All The Colors of Life: A Celebration of Fred Ho”

Bill V. Mullen, “A Hundred Flowers of Revolutionary Hope”

Diane Fujino, “Fred Ho’s Radical Imagination”