The “New Society” had its own tricks. Billions disappeared from the nation’s coffers, clowns filled legislative positions.

September 23, 2022

The following personal essay is part of the Against Forgetting notebook, with art by Neil Doloricon.

Obsessed with the “true, the good, and the beautiful,” former First Lady and Metro Manila Governor Imelda Marcos had a fondness for spectacle not unlike that of the perya or karnabal (carnival). Everything had to be grand, from her bouffant bun and buildings rising from the sea to parades like the Kasaysayan ng Lahi (History of the Race), film festivals, and beauty pageants. In the same way that circuses had magic acts, clowns, animal trainers, and “freak” shows (featuring the exploitation of the disabled, the deformed, and the exotic), the “New Society” had its own “tricks.” Billions disappeared from the nation’s coffers, clowns filled legislative positions, and politicians were seen as “lapdogs” of puppet masters. Those who dissented were considered aberrations in the new order, and thus had to be hidden away in military safehouses or detention centers, incarcerated, or “disappeared.”

But there was Imelda to entertain. In one of her famous quotes, she justifies the ostentatious display of wealth with these words: “I have to be beautiful so that the poor Filipinos will have a star to look at from their stars.” Just like a true zarzuela star, she also entertained through music, singing “Dahil sa Iyo (Because of You)” during Ferdinand Marcos, Sr’s presidential campaigns. Shortly after the declaration of martial law in 1972, it was also the First Lady who commissioned songs for the regime. These marching songs, with buoyant melodies and hopeful messages of a new society, would form my earliest memories of life after Proclamation 1081, which officially ushered in martial law.

Arguably the most popular was “Bagong Pagsilang (literally, Rebirth, also known as March of the New Society),” with lyrics by Levi Celerio and music by Felipe de Leon. It was this song that was played over and over on the radio and television, taught to and sung by school children like myself, and according to political prisoners, such as Bonifacio Ilagan and Judy Taguiwalo, was constantly forced upon them to listen to while in detention.

Less popular but equally moving were “Bagong Lipunan (literally, New Society, also known as Hymn of the New Society),” “Mabuhay ang Pilipino (Long Live the Filipino)”, and “Pilipinas Kong Mahal (Philippines, My Beloved).” These songs, along with the folk songs “Pamulinawen” in Ilocano and “Dandansoy” in Ilonggo, were compiled in an album called Mga Awitin at Tugtugin ng Bagong Lipunan (Songs and Music of the New Society), 1973, performed by the Philippine Constabulary Band conducted by Lt. Col. Honorato San Pedro.

Eight years later, then-First Lady Imelda Marcos commissioned another song, “Ako ay Pilipino (I Am Filipino)” from popular composer George Canseco. Music, as well as the visual arts (paintings by Evan Cosayo of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos as mythological creatures Malakas and Maganda or the Strong and the Beautiful), film (Iginuhit ng Tadhana, or Written in Destiny, 1969, directed by Mar S. Torres), and literature (Ferdinand E Marcos, An Epic by Guillermo C. De Vega, 1974, and Imelda Marcos, A Tonal Epic by Alejandrino Hufana, 1975) proved how culture was used as propaganda by the regime to paint a picture of an ideal and prosperous society in spite of the reality of political repression—not unlike the whitewashing of walls to hide the slums behind them.

I was ten years old at the time of Proclamation 1081, and after half a century, I remember only suspended classes, curfews which resulted in the arrest of people caught outside between midnight and 4 a.m., and later in high school, CAT or Citizens’ Army Training, which meant studying how to march with a wooden gun, and not much else.

However, things changed in college at the University of the Philippines (UP). I promptly joined the UP Repertory Company (UP Rep), and in my sophomore year in 1980 was cast as Magsasaka 2 (Farmer 2) in the second staging (the earlier one being in 1977) of Bonifacio Ilagan’s “Pagsambang Bayan (People’s Worship),” directed by Behn Cervantes. Perhaps I was Farmer 3, or 4, or 5—it didn’t really matter. None of us had solo lines, as we spoke as a chorus of farmers. But I do remember saying lines that told of how we produced food and yet were hungry. Written in the form of a mass, the play told of the dilemma of the church (as represented by the priest), faced with the problems presented by peasants, workers, youth, and indigenous people. To this day, I can recite lines from the play and sing the songs. In hindsight, it was reciting those lines and singing the songs that perhaps made me understand, and empathize with, the characters of the play and the people they represented.

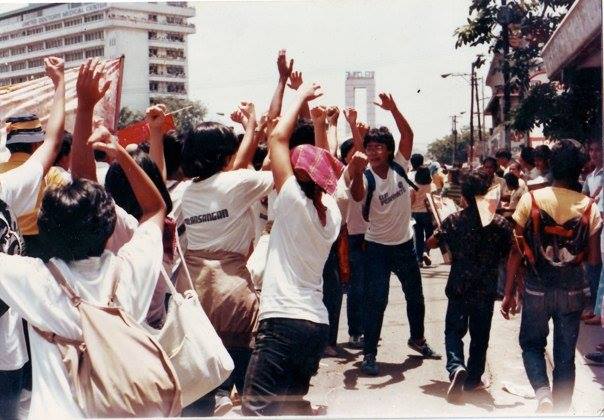

At around that time, in July 1980, students called for a rally in front of the Department of Education in Arroceros, Manila to protest the Education Act of 1980, as it was then called, which threatened to curtail academic freedom. It would be signed into law in 1982 by then-President Marcos and would subsequently be called the Education Act of 1982. The act was unacceptable to many students and we were enticed to join the rally. I had never joined a rally outside the university, but I was not afraid because UP Rep arranged for us to go as a group, formed a “buddy” system, and told us that we can ride the buses (probably arranged by the UP Student Council at that time).

Unlike most college students, I preferred floral dresses to T-shirts and jeans. It must have been all those Seventeen magazines I liked to read, and so I went to the rally in a dress, obviously not the best choice for such an activity. Not long after the rally started, it rained, and soon after, there was a commotion, because police officers had been ordered to disperse the rally using truncheons. I ran with the others and predictably fell because of my wedge sandals (I did not wear rubber shoes because they would not match the dress). But someone picked me up, and either pushed or dragged me into a building where many students had taken shelter from the police and the rain.

I don’t remember how we got back to the university, but I do remember Chris Millado meeting with the cast and crew of Dulaang UP’s twinbill plays, Bienvenido Noriega’s “Lilipad Pag Pinalad (Fly if Fortunate)” and Isagani Cruz’s “Kuwadro (Portrait),” a monologue starring then–cinema legend Miss Rita Gomez. At that time, I was one of the lighting crew of these two plays, proudly in charge of the spotlight for Ms. Gomez, using my innovative potholders. Chris was at the rally as well, and he urged us to join him in a new production that would be called “Bodabil” (Vaudeville), to be staged at a tent theater just across from the UP Faculty Center.

No, I did not perform in Bodabil’s first run. I had already joined Pagsambang Bayan. But I did play an important role in that production. I took charge of refreshments, although most of the food I brought came from leftovers from the other play, as I was chair of the refreshments committee of Pagsamba. Later, after Pagsamba finished its run, I alternated for a couple of insignificant roles in the play (as I had a poor singing voice)—I think I was Broken Shields (the magician’s assistant)—as we took on names that were patterned after Hollywood stars in the same way that Filipino vaudeville star Canuplin was named after Charlie Chaplin.

From that play was formed the organization UP Tropang Bodabil, (first chaired by Chris, and from 1982–83 by myself). Later, the organization split up and we formed the new group as Peryante, meaning fair or carnival workers (first chaired by Ralph Peña). From 1980 to 1986, Bodabil and Peryante combined, we became known as a street theater group. Our most popular plays included “Ilocula, ang Ilokanong Dracula (Ilocula, the Dracula from Ilocos) I and II,” “Miss Young Multinational,” and the long street play “Oratoryo ng Bayan (People’s Oratorio),” first performed by the Philippine Educational Theater Association (PETA) in 1983, and which we restaged in 1984 with the group of street singers, Patatag.

Of our performances, a few stand out. One was in 1981, at the UP College of Arts and Sciences lobby, where we staged “Ilocula” at the oath-taking of newly-elected student council president Lean Alejandro. The play had actually been based on an article Alejandro had written entitled, “What are We in Power For?” published in the Philippine Collegian in 1980. I remember singing, “We are Family,” and dancing the swing.

Another memorable performance was in 1984, during the Lakbayan march calling for the boycott of the Batasang Pambansa (Legislature) elections. Chris and I had signed up to join the seven-day march from Tarlac to Manila, although technically, we started on Day two in Pampanga. We walked with the marchers, most of them farmers, for several hours a day, chanting as we marched, and stopped at a designated town, met by supporters. Rallies were held in the afternoon and cultural programs in the evening. Chris and I emceed the evening program, and we were joined by theater and music groups that were either local or from Metro Manila.

It was in Malolos, Bulacan, that our theater group Peryante joined us to perform Ilocula II. Chris had rewritten the play and instead of focusing on the Marcos family, it now focused on their cronies, the military officers whose guns and tanks gave the regime its teeth—Prime Minister Cesar Virata became General Bareta, while Armed Forces of the Philippines Commanding Officer Fabian Ver and Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile became twin monsters Revolver and Barrile. I wrote the songs for that play, perhaps the first songs I had written— I did not think of myself as a writer at that time. And happily, that evening in Malolos, we were hosted in the ancestral home of Nicanor Tiongson (then my professor and an esteemed scholar)—a departure from the school houses and churches that usually sheltered us.

We explored several street theater forms. There was the kilos-awit (movement-song), which we performed during marches. We would go to the sidewalks, sing the song “Awiting Rebolusyonaryo (Revolutionary Song),” from the 1940s, and then run to catch up with the march. There was the improvisational play, as exemplified by “FQS (First Quarter Storm),” on the student movement of the late 1960s and the early 1970s, just before martial law. Augusto Boal’s “Theater of the Oppressed” influenced a newspaper theater play which used the boxing form. And finally, there was “Oratoryo ng Bayan (People’s Oratorio)” co-directed by Chris, Ces Manggay (later Manggay-Quesada) and Ching Arellano, in December 1984. The play combined several street theater forms and strategies: improvisations, the kilos-awit, puppets, and men dressed as ballerinas while Ces herself did a parody of Imelda singing about the true, the good, and the beautiful.

Yes, we sang “Bagong Pagsilang” as well, also as a parody of the regime’s fantasies of an orderly society, with actors wearing uncannily real Ferdinand and Imelda masks (made by the talented actor Paeng Altavas) and waving to the crowd, joined by an unmasked student actor, Beth Torres, playing the daughter Imee in a Kabataang Barangay T-shirt.

I believe my martial law story is best told through songs: those that were commissioned by the regime, those that we parodied, and those that we wrote and sang so that we could give voice to the sentiments of the oppressed, the incarcerated, and the victims of the fascist regime.

As I compose this essay, I realize there are details I cannot remember and perhaps moments I remember incorrectly. As I have emphasized in a poem I wrote several years ago, we always need to question the unreliability of memory. But my hope is to share with you my memory of the “carnivalesque” (to borrow from Mikhail Bakhtin), and how we were NOT invincible heroes dodging whizzing bullets grazing cheeks. We were simply clowns in a time of repression. Yet I would like to believe that fifty years later, many of my fellow theater artists and I remember martial law with both humor and steadfast commitment to the national democratic movement.