“Magic and writing, it’s all misdirection, defamiliarization, and at its best, the ahhhhh moment of surprise.”

March 18, 2019

Nothing is steadfast in the childhood of Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls, only a slow unraveling. An only child born out of an affair between her wealthy white shoe-brand father and her Chinese-Hawaiian model mother, Madden went back and forth between the chaos of her home, where her parents struggled with drug and alcohol addiction, to the misery of her Boca Raton private school, where she faced ostracism as a queer biracial girl.

Madden writes, “I wanted love the size of a fist. Something I could hold, something hot and knuckled and alive.” To contain, to hold, to be vulnerable—these intense desires both shape and propel her exploration of grief, trauma, pain, and forgiveness. Composed as a kaleidoscope of darkly shimmering fragments, this courageous debut memoir is the documentation of one woman’s attempt to write down and rewrite her own history, so as to make space for more love.

Madden writes, “I wanted love the size of a fist. Something I could hold, something hot and knuckled and alive.” To contain, to hold, to be vulnerable—these intense desires both shape and propel her exploration of grief, trauma, pain, and forgiveness. Composed as a kaleidoscope of darkly shimmering fragments, this courageous debut memoir is the documentation of one woman’s attempt to write down and rewrite her own history, so as to make space for more love.

I had the chance to speak with T Kira on a freezing afternoon in January. She welcomed me into her cozy home, where there were glowing candles, a pot of roasted buckwheat tea, and two energetic poodles who insisted on sitting around for the conversation.

—Pik-Shuen Fung

Pik-Shuen: I read in an interview you did a few years ago that you were on your third or fourth attempt at a novel at the time. How did you end up publishing a memoir first?

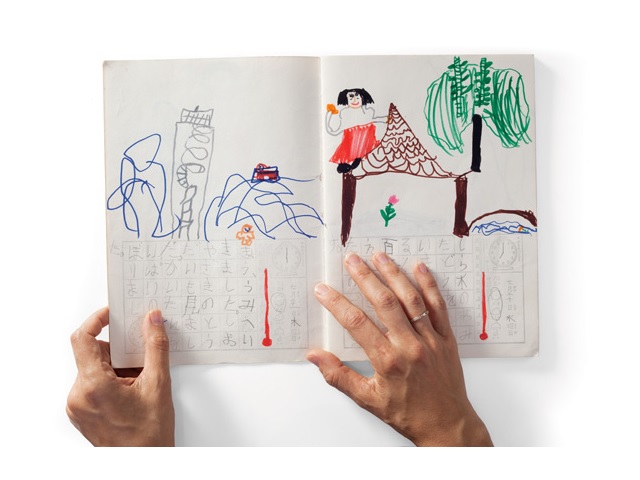

T Kira: I’m traditionally a fiction writer. I graduated with my MFA in fiction and I’ve taught fiction for years. I applied to the MacDowell Colony with a novel and got in off the waitlist, about a month and a half or two months after my father died. I almost didn’t want to go, but I decided to give myself that space to try to make art and heal. While I was working on the novel, my dad started showing up as a character in all of my work. At that point, my fiction had always been radically removed from my reality, and it was odd for me to have any real people popping up in my stories. I decided to embrace that, him, and try to wrangle whatever it was that was happening, so I wrote about loving a mannequin who stood in for a father. It was the first piece of nonfiction I had ever written. While I was grieving, all my other projects felt frivolous. I remember calling Hannah, my fiancée, and I said, If I were ever a nonfiction writer, which I never will be, this would be an interesting book, and this is what I would call it, and this is how it would look. She said, Maybe that’s the book you’re ready to write. By the time I left the residency, I had 100 pages of something.

Can you talk about the process of writing your memoir? Did you draft all of it and then revise, or were you revising along the way?

I’m a really slow writer. If I don’t have a sentence right, I’ll spend a whole day or week on the sentence. Because of that, everything takes me a lot longer, but I also feel like I’m closer when the draft is finished.

In my state of grieving, I wrote an accelerated draft: 120 pages in six weeks. That’s more or less where it was when I signed it to my agent, Jin Auh, who is wonderful. She helped me grow the manuscript. Since then, it’s tripled in size, and I worked with both her and my editor through gaps in the story and developing a more linear through line. Even after I signed the book to Bloomsbury, I kept writing it because the events and discoveries of the book were happening in my life, in real time. I’ve had many false endings of Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls, which, in the end, is what I think the book is about.

Formally, it made me think of a memoir composed of fragmented essays. Did you know this was the form you wanted from the beginning?

I wrote the book by writing little fragments. That’s how I prefer to write fiction as well. Even the novels I’ve been working on have been fragmented. When I submitted the project to Jin, it was a collection of essays. In my first meeting with her, she crossed it out on the cover and wrote: memoir. She could feel that I was being reductive of my own work. At the time, I knew so little about memoir and I had so much catching up to do. I studied Russian literature in undergrad and then fiction in grad school, and there was this big gap in my knowledge of memoirs and what they could do. I thought essays were the more “sophisticated” option.

As soon as I understood that I was, indeed, writing a memoir, I started reading every memoir I could get my hands on. That’s all I’ve read for three years. Once I started reading memoirs and taking my time with them, I saw how fiercely intelligent and innovative they could be. I saw what different writers did to break the “traditional” form of memoir, and how beautiful traditional memoir can be as well.

What are some of your favorite memoirs that you read during this period?

Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s The Fact of a Body is one of my favorite books I’ve ever read. Alex is brilliant. They handle time in that book like no book I’ve ever read before. Reading Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch and tracking that fragmentation—how fragments feel truer to certain lived stories—that was important for me. Jo Ann Beard’s The Boys of My Youth is called essays but also feels memoiristic, and that book, just the language alone, stunned me. I always look to Jo Ann Beard for her music and her care and her ear. What else? Samantha Irby is so delightful. She finds such electricity in the mundane. She could write about anything and it would feel so storied and so full and so funny and so sad. Yiyun Li is remarkable. I think Myriam Gurba did some incredibly big work in her memoir Mean.

I felt there was so much compassion and generosity in your writing, and yet at the same time you depict your past and your family members with such brutal honesty. Were you afraid at any point of your family’s reaction? Did anyone have a say in what could or could not be included?

I’m terrified, still. I’ve had an ongoing dialogue with my mother the whole time I’ve been writing this book. I talked to my mother and my two half-brothers before I started writing it at all—I said, would this feel okay with you? Do you feel I have the right to do this?—and they said yes. There’s no easy answer for how to handle writing about the people you love most. Lidia Yuknavitch said you should always be able to sit in a room with someone you’ve written about, with the exception of anyone who has abused you. I like the idea of that. I feel like I did my best to honor the people in the book without cruelty or malice. Anyone I care about, I’ve reached out to, even minor characters in the book. I made a list of the people for whom I would make changes if it made them uncomfortable. It’s been awkward because in some cases I haven’t spoken to the person in fifteen years. It’s been painful. It’s a constant dialogue and a person’s feelings about it can change every day, but that’s the responsibility we take on if we’re writing nonfiction. There are other people in the ring. And there is never a final reaction.

What kind of research did you do for this book?

The most difficult was the final section, “Tell The Women I’m Lonely”, because I was writing about a different time period, a time before I was born. I was interviewing my family members and my mom a great deal and, as time tends to do, everyone was giving me different stories. It was actually really incredible to see how three different people could remember things so differently. I started doing some research on memory function, time, groupthink. In the end, I think that final section is about the impossibility of getting it all right, about the constant revision and revisionist histories, about memory changing and expanding and contracting.

I liked what you said in another interview that with fiction, you focus on closeness, whereas with nonfiction you think more about distance, and how to block your current consciousness from leaking into the story you’re trying to tell about being eight or being sixteen. I think you do that really well in this memoir and I was wondering if you could talk more about how you were thinking about that either in drafting or revision.

I think when I first wrote Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls, I really tried to stick to the consciousness of that age and the voice of that age. I was trying to be as true as possible. The Fact of a Body was the book that really inspired me to open up more slips in time. To me, the most mesmerizing moments of that book are when Alex pauses the scene and allows their present self to come in, to speak. Time collapses before the scene can continue. There’s power in that kind of move; there’s friction whenever a present consciousness comes to play with the self of a different time. Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape is a perfect example of that.

So, while my first draft was more streamlined, through revision, I added more flash forwards, more time play. I wanted that claustrophobia. I wanted the new questions that come when confronted with different versions of the self.

If you could go back and tell yourself one thing, as you were beginning to write this book, what would you say? Is there anything you wish you knew?

My concern has been very other-people-centric from the beginning. Even before I knew it was a book, I felt guilty that other peoples’ stories were not mine to tell. When my students ask me about this, I emphatically express that everyone has their individual versions of truth and experience and we all have the right to those experiences—but it’s more difficult to convince myself that it’s okay. If I could go back, I would tell myself to own my experience and stop worrying about getting everyone else right. Truth and reality are relative. Truth changes depending on what body is holding it. That’s a summarized version of my Author’s Note at the beginning of the book, but I wrote it last. Oh, I wish I knew that first.

That makes me think of what you said earlier about the people you interviewed. Everyone has a different telling of what happened of the exact same event.

I wish I knew that upfront, instead of having this obsession with getting it right. How does anyone get everything right? They don’t. It took writing this book to realize: of course it’s a projection. It’s not you. You’re telling the truth by building a story to the best of your abilities. Even though I tried to get other people’s stories in my book, it’s still my book and my rendering of it, so it’s really just my reality. All the realities that live inside a single person—that’s enough for me to try and wrangle.

I’m curious about your writing process after you completed the last edits for your memoir. Have you felt any pressure or expectations for your next book, to write something entirely different?

I feel nervous that I won’t be able to return to fiction in an effective way, or that maybe I was never writing it effectively in the first place. But fiction is, will always be, my love. I want to prove myself in the fiction ring. I want to succeed at writing a novel, which I have failed at many, many times. I’m just using different parts of my head and my body to write fiction again, different corners of my imagination. I’m really excited about my horror novel. It’s been going for a long time in different iterations. I’m still trying to figure out the right form.

What about horror in particular are you drawn to?

I’ve been drawn to horror and the grotesque for as long as I can remember, even though I am a fear-based person and see death and danger in everything. I think it was also Lidia Yuknavitch who said children are fear-based or rage-based when they’re raised in abusive households. When I took a workshop with Lidia, I remember she read a piece from this book and said, I want to see where your rage lives. She said, I can feel it. I can see it in you. Where does it live? It’s a question that changed my life. I’ve been thinking about that a lot, that maybe horror is where my rage lives. It’s this leaning or attraction to the horrible, somehow. My first stories from when I was seventeen or eighteen were about severed limbs and organs in glass jars. I’ve been thinking, what a weird move. Why did I write about that? It’s not how I live my life. I’m a very gentle person. So I don’t know.

Can you describe what a typical writing day looks like for you? Do you have any routines or rituals?

I work really well with incentives. So if I have a reward planned for later, if I get to go out to dinner or cook something special or see somebody, it’ll push me. I work really well to please other people, so I like deadlines. I think it’s really noble when people write for themselves and it’s their meditation and their practice, but I’m not that person. I write to please other people. I hate disappointing people or letting anyone down. So I tell everyone I work with, whether it’s an editor at a magazine or my agent or my editor at Bloomsbury, give me a deadline. I will make that deadline.

I also always work with word banks. I have a million post-it notes on my computer and physical post-it notes everywhere. As I’m reading any book, I’m writing words down—interesting words, words with pop, words used in new ways, words that make me catch my breath. I have pages and pages and pages of words. So to get started, I’ll look at those post-its or banks and I’ll take one post-it, say with seven words on it, and give myself the prompt to use all of the words in a page or two. Just to get sentences moving until I can feel what the piece wants to do or what it is.

Do you have any other reading habits? Is there anything else you note when you’re reading?

Always words, always phrases. I’m definitely a sentence-first person. I can quote so many lines of books and I won’t remember what the book was about or what happened. I tend to think of readers and writers as plot-centric or language-centric. I’m definitely the latter. I think about every syllable almost scientifically. I love the Gary Lutz essay, “The Sentence Is A Lonely Place.” When I share it with students, they think, this is ridiculous—how can anyone read like this? It’s so tedious. And they’re right and it’s true, but I love to read that way!

I like to read things twice, so the first time I can be dazzled by all the sentences and the second time, I’m understanding more of what’s happening, because I’m slow to that. I’m slow with understanding what’s happening in my own life, nevermind in art. In movies, too, I’m looking at the composition and the colors and I’ll miss that somebody died. I’m more interested in tiny details, you know? I want to experience something that feels like a magic trick. I’m always trying to break it down. How did that happen? How did it change me so quickly?

So besides being a writer, you’re also a photographer and a magician. Do these different practices inform each other? Have you learned things from one that you’ve brought into the others?

Photography, I haven’t been doing it as much anymore, sadly. I’d like to start again. When I was in grad school and soon after, I was interested in these character portraits of people, like in Jayne Anne Philips’s book Black Tickets. She didn’t have the ABC plot arcs, but she had these bursts of people, bursts of mood. I was really inspired by that—writing into one character for a page or two with really heightened language until they felt textured and real, until it felt like portraiture. I tried to bring that into my photography. I’ve always been most interested in the portrait.

Magic has always been the way I approach writing and stories and teaching. With magic, I’m always looking for the moment where I feel amazed. I’m always looking for The Look on other peoples’ faces. But discovering how the illusion is pulled off is never a disappointment for me the way it is for other people. It’s the same with writing for me. Finding out how it’s done and breaking it down makes for something so much richer. I want to figure it out. Did that sentence just give me the shivers because of this word, or is it because it ended in one syllable? How did that just work its way through my body? Magic and writing, it’s all misdirection, defamiliarization, and at its best, the ahhhhh moment of surprise.