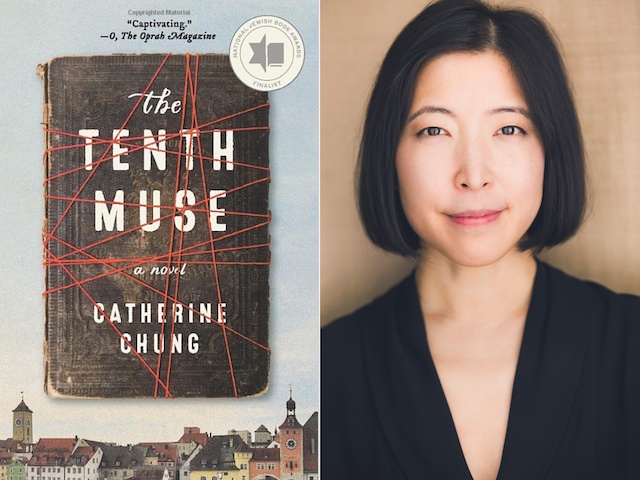

The author of The Tenth Muse talks about writing about women intellectuals, Korean myths, and writing against Western narrative conventions.

April 29, 2020

The arc of a story, or so we are taught, follows a hero through rise, climax, and fall. Years ago, Catherine Chung heard a different theory—a suggestion that this approach to narrative was a rather male way of thinking—and has been playing with alternative structures ever since. For her enthralling second novel The Tenth Muse (Ecco Press), about the life of a brilliant woman mathematician, Chung looked to other models for inspiration: the looping way women often tell each other stories, as well as the Buddhist worldview of the folktales her Korean parents told her.

In a little cafe on the Upper West Side, just before our city went into lockdown, I had the chance to sit with Catherine and talk to her about story structure, and all its exciting possibilities.

—Pik-Shuen Fung

Pik-Shuen Fung

In an interview you did with The Rumpus last year, you talked about how you wanted to write away from the Western Judeo-Christian tradition—that you were inspired by the stories your Korean Buddhist parents told you. Could you say more about the difference between these two traditions of storytelling? How did you go about doing this in The Tenth Muse?

Catherine Chung

As a writer, I’ve always felt constrained in some ways by the expectation that I would conform to the kinds of stories I read in school or later in workshop, which were so different from the kinds of stories I was told at home, or even the Korean dramas my mother watched on television. There were ways in which those stories didn’t make room for the story I was living in, or the stories I came from. I’ve felt that constraint since I was a child, and didn’t want to yield to it in my writing.

I wanted to be able to include the stories I grew up with but to tell them from the point of view of somebody who is an American citizen who has spent her whole life in America. I wanted to be able to include the entirety of my perspective, which has often felt at odds with itself.

In workshop, I was taught that one thing to avoid was sentimentality. Another was coincidence. I think those are very Western, maybe very American storytelling conventions. The Korean folktales, stories, and dramas I grew up with were full of sentiment and full of coincidence. And it makes sense to me that they would be. Because when you come from a culture that traditionally values familial connections and duty above all else, then yes, those stories are going to be full of feeling between parents and children and siblings: love, regret, grief. And when you come from a country that has a history as turbulent as Korea’s, one that includes occupation, famine, war, extreme poverty, and a staggering economic rise—well, coincidence might play a much bigger part in your life.

I grew up hearing stories about how people escaped from conditions of war, and it was always some wild coincidence or immense stroke of luck. And the stories in which people were reunited with loved ones they hadn’t seen in decades always required what might seem an improbable coincidence to bring them together. As an immigrant, what I’ve learned is that the world is both enormous and very small— what we consider improbable happens all the time if you’re already living an improbable life. And if you don’t allow for that kind of story, then you’re dismissing the lived reality of many people’s lives.

I was raised Buddhist, and I felt that in so many ways that gave me a completely different worldview than the one that was always assumed in the English books I read, or even the conversations I found myself having in school and with friends. It gave me a completely different philosophy about life, about conflict, about the trappings of language or ideas themselves, about hardship, and my place in the world. There’s no sin in Buddhism, no good, no evil. That’s not the lens through which the world is ordered (in fact it resists all lenses, and all such ordering), so I was thinking all the time about how to bring that into my book as well. I didn’t want to constantly be choosing between the tradition I was writing in and the tradition I had been born into.

PSF

That’s something I think about a lot, too. At least, I’m thinking about how Western stories are so focused on the narrator or the protagonist…

CC

And their personal journeys! Right, right. As a writer, and even just as a person, I’ve always been preoccupied with how our interactions have ramifications on other people. Not just our individual lives, or the arc of the story we think we’re living in, but how it affects the people around us.

I also think the way I view happiness is somewhat different than the American notion of it. A lot of people think that my book ends sadly, you know, because my narrator doesn’t get every single thing that she wants. I don’t see it that way at all. I feel like if you get out [of this life] with your integrity and a fair amount of success, you’ve done pretty well for yourself. But I was also raised by parents who came from a culture that didn’t think personal, individual fulfillment was the end goal.

PSF

Would you say, in terms of the structure of your novel, you were thinking about a different definition of happiness?

CC

Yeah, I think so. I like that: a different definition of happiness. A different definition of what the arc of any individual’s life should look like, or how we should measure that. There were two founding myths in this novel. One was made up, but based on Greek mythology, about the Tenth Muse, who decides she doesn’t want to be a muse at all but to tell her own stories in her own voice. Then there’s the story of Kwan Yin, who is this bodhisattva who basically gives up all worldly power to help the suffering. But even when she’s welcomed into the Gates of Heaven, she says that she’d rather stay in the world helping people until all suffering is alleviated.

These two stories feel like they’re in opposition, but I don’t think that they have to be. For me it’s more a matter of figuring out how to balance these two perspectives without abandoning one. And exploring whether that’s even possible. Is it possible to honor the well-being of your community while also not totally sacrificing yourself? And in terms of storytelling it felt like the challenge was, how do you introduce these different values that are not necessarily universal values and let them interact with each other? You know, it’s funny, I’ve had conversations with my bilingual friends about how we think differently in our different languages, and one of the challenges of writing for me is how do you get both modes of thought into one story, or one book, in one language?

PSF

What other books did you read that have different structures?

CC

When I was writing the book, I was re-reading Dream of the Red Chamber and A Thousand and One Nights. And I was thinking about how really rewarding, enriched, and delightful stories can be, when they are circular, or when stories interrupt themselves, or when stories we would say “go nowhere” aren’t about the plot per se so much as they are about the relationships people are forming. Where the question of the relationship isn’t framed in terms of conflict, but how it reveals who these people are, and what kinds of decisions they make, and how they operate within a very complex set of rules.

In terms of contemporary fiction, everything Helen Oyeyemi writes delights me because of the way she always breaks open narrative and surprises me. I probably had Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit on my mind, as well, as a book that disrupts what my sense of narrative can do, and my God, three Korean books I read in translation: Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, Bae Suah’s A Greater Music, and Eun Heekyung’s Nobody Checks The Time When They’re Happy—they broke every rule of storytelling I’d been taught in school, and were so intense and uncompromising in their artistic vision. I wouldn’t call them happy reads, but they were astonishing, joyful reads for me. It was incredibly liberating to be reminded that some literary conventions and modes of thought that feel like fixed rules are just conventions after all, and there was also something incredibly empowering about getting to enter a contemporary Korean consciousness in each of those books, which is something I hadn’t often had the pleasure of experiencing in my reading life before.

I also read Ali Smith for the first time while I was working on The Tenth Muse, and it was a revelation. There’s a simultaneous looseness and control there, and then a dazzling playfulness and breadth and depth to what she covers that was exhilarating to read. After I turned my book in, I read Idra Novey’s Those Who Knew which just took my breath away with its inventiveness and rigor. Miriam Toews’s Women Talking was such a brilliant book, so formally and structurally interesting, and it painstakingly builds an entire worldview through a conversation that a few women are having and the stakes are just immense. I loved it so much. Trust Exercise by Susan Choi. Days of Distraction by Alexandra Chang just came out and everyone should read it—she does so much so gracefully that I feel like I’ve been trying to do, or wanting to learn how to do…

PSF

I read your debut, Forgotten Country, after reading The Tenth Muse. What was it like to write your second book in comparison to your first? Are there things you learned in writing your first book that you were able to implement in the second? Did you have a different set of concerns or goals?

CC

My first book was basically the distillation of every thought I’d ever had. Ever. Then I had to edit that into a story. I had no sense of what a novelistic structure might entail until after I’d written many drafts and thought, Oh, maybe this is what a structure is. Writing that first novel taught me what a novel was.

With the second book, I had a working philosophy of what a novel’s structure entailed for me. I now sometimes read this structure into novels where it may or may not exist—but I think for me, when I write a story, I’m always resisting something. Even as I’m reaching for something, at the same time I’m always resisting that thing I’m reaching for. And the structure comes together when the book breaks me, when I can’t resist and I have to give in.

So in the first book, the narrator’s father is sick and the whole time the narrator is trying to hold onto him, and to hold onto her sense of self and her sense of family and history. It wasn’t until I realized she had to break that, and that involved her breaking herself and me breaking the story, that it would come to a moment where she would be confronted with the cost of holding on and it would force her to let go.

For me, that’s the climactic moment of the book. It’s not about the achievement or failure of a goal. It’s the moment where the character grows beyond the structure she’s living in, where I as the writer realize, Oh, I can’t actually continue beyond this. The story has to break. Her mind has to break open so that this new reality can be something she grapples with.

When I started The Tenth Muse, I already had that in mind. I understood that I would probably be writing towards something, but that the book would become finished for me when I broke open the structure that I was building and made space for something new.

That’s also how scientific breakthroughs happen, right? You use the science that exists to try to open up a new understanding that did not exist before. So I thought, this is how stories work. This is how books work. This is how any breakthrough in any field works. You get as far as you can, and then something has to crack open. So I was waiting for that in this book, and it helped to know what I was waiting for, or even, what I was working towards.

PSF

Can you talk more about what you were working towards?

CC

So I knew from the very beginning that I wanted to write a book about a brilliant woman mathematician. In fact, it happened because I had been given advice when I finished my first book by somebody in publishing, who said to always remember that I wanted the audience at my events to like me. She said, the thing that you have to be careful of is to not sound too intellectual.

And as a woman writer, it was really disorienting because I think that writing a book is fundamentally an intellectual endeavor. You’re trying to share something that’s in your mind with the mind of somebody else. I also think that you don’t write a book to make people like you.

So I thought, the next book I write, I’m going to write about a woman intellectual. It was this tiny rebellion. Around the time I made that decision, I read this article about the five most influential women in mathematics and history. And I was struck by the fact that I had never heard the names of any of these women despite being a math major. I thought, I’m going to write about a brilliant woman mathematician intellectual.

What was interesting is that sixty pages in, I realized that I had completely failed because I was writing from the point of view of a man who had been in love with such a woman. I thought, why am I writing this book? As if what’s important about this woman is that this man was in love with her. So I started again. Then, the woman was a failed mathematician. She was a math historian instead. I realized that there was this weird hitch in my brain that was holding me back and making it really difficult for me to imagine a successful woman mathematician. I found myself constantly tripping over my own limitations and the limitations of my own imagination.

PSF

You mentioned you knew you would have the story when something in the structure broke open.

CC

I started out thinking that this novel would be a story about this woman’s career. It wasn’t until something happens in the book with a romantic partner, who is also a colleague of hers, that I realized that it’s not just about her career. It’s also about the demands that a single-minded approach to your career can make on you and how there can be a personal cost.

I mention these two stories in the novel: the story of Kwan Yin and the story of the Tenth Muse. When I started this book I thought very much in terms of, which story do you have to choose? And I realized, Oh, it’s not about choosing one or the other. It’s not about either succeeding within the system, or being broken by the system. It’s how do you find freedom within the system to have a kind of personal integrity?

Not, do I achieve career success or do I give up career success, but can I define my decisions in terms of what is right for me? To not have the markers of the decision making process be: am I sacrificing everything, or am I living my dream? But more aligned with the question, can I see the world more clearly in the world that I live in? Given my own constraints and those of the society that I live in, how can I make a decision—not necessarily the right decision or the wrong decision in any absolute terms, but one I can live with?

PSF

I think that’s why I loved the book so much and why, when I read it—I felt as if this was a mentor speaking to me about her life.

CC

I tried to write a mentor for myself as well, actually! Because I felt we needed one. I wanted to write someone who was talking directly to us. To say: I lived this life with obstacles that were in some ways much greater than your own, and this is what I learned.

PSF

When I think back to what you said earlier about people thinking the ending was sad, I feel that whether it’s happy or sad is beside the point. Instead, here is a woman who really lived true to herself, every step of the way. Which is so hard. I mean, it’s hard now, but it was even harder then.

CC

And I think it is so hard now! It’s so hard to do. I love that you say that, because for me, the triumphant moment of the book was when she chose that as the way that she was going to live her life. It opened something up for me: a possibility I found liberating.