The author of Conjugating Hindi on leaving New York, Afro-Asian solidarities, and learning Hindi

April 22, 2020

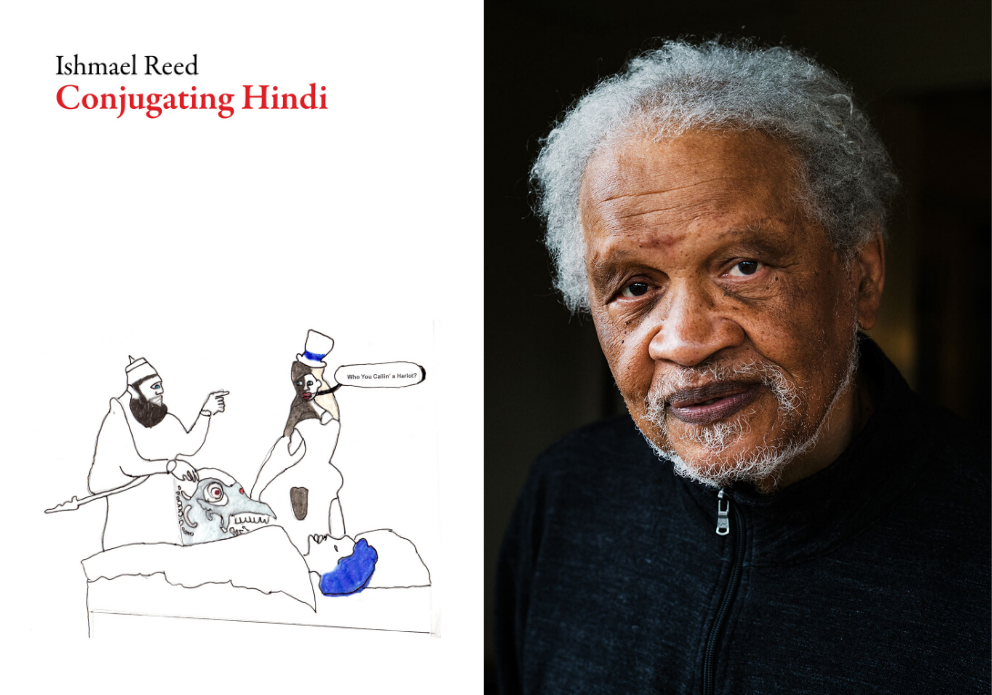

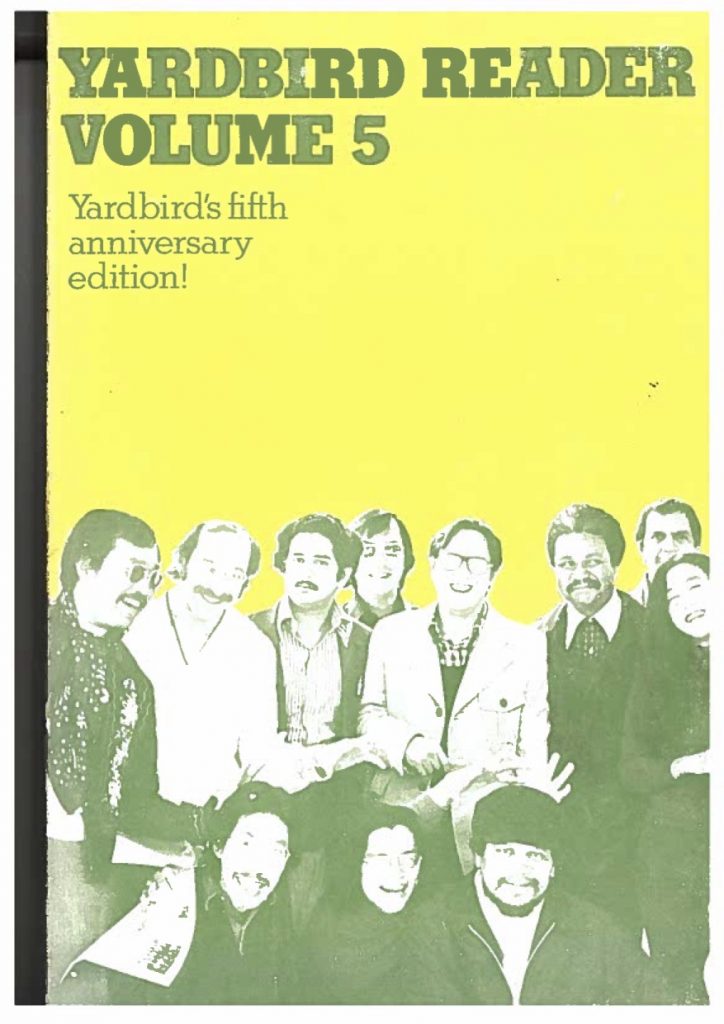

Over the last six decades, Ishmael Reed has written ten books of poetry, including Cab Calloway Stands in for the Moon or D Hexorcism of Noxon D Awful (1970) and Chattanooga (1973), twelve novels, including Mumbo Jumbo (1972), Flight To Canada (1976), and Japanese By Spring (1996), a dozen works of nonfiction, including God Made Alaska For The Indians (1982) and Blues City: A Walk in Oakland (2003), and a volume of six plays, simply titled Ishmael Reed, The Plays (2009). Originally from Buffalo, Reed established himself in New York City before moving to Oakland in 1969. With Al Young, Bob Callahan, and others, he established the Yardbird, Y’Bird, Quilt, and Konch literary journals, which published early work from emerging writers like Frank Chin, Ntozake Shange, Jessica Hagedorn, Leslie Marmon Silko, Victor Cruz, Wakako Yamauchi, Joy Harjo, and Ken Chen.

Reed, now 82, has maintained his intellectual and political independence from the American media, publishing, and entertainment industries. He has publicly raised questions about race and representation in Steven Spielberg’s adaption of The Color Purple, Lee Daniels’ Precious, and David Simon’s television series The Wire. His recent play, The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda (2019), challenges the history behind the Broadway play Hamilton. Cornel West recently included Reed in a short list of writers who “rejected status” (”Baldwin, Amiri Baraka, Ishmael Reed, Gwendolyn Brooks”) to write “from the depths of their souls.”

Such writing came with a cost. Since the 1990s, literary journals and magazines have tried to ignore Reed’s books. His latest novel, Conjugating Hindi (2018)—which follows a right-wing Indian American who hides out with a leftist African American intellectual after white mobs hunt down Indians—went unremarked upon in the traditional press.

In this interview, conducted over four meetings (from May 2018 to September 2019), we discuss racism in the New York poetry scene, institution-building in Oakland, the inspiration for Conjugating Hindi, and his long history with Asian American writers.

—Rishi Nath

Rishi Nath: I’ve seen a picture of you on stage with Malcolm X.

Ishmael Reed: It was 1960. The photo was taken at a community center in Buffalo. I was writing for a newspaper, The Empire Star, founded by A. J. Smitherman, the hero of the 1921 Tulsa Riots. Joe Walker succeeded him at the paper after he died. Joe was 27, I was about 22. We had a radio show called “Buffalo Community Roundtable,” and Malcolm X was one of our guests. We lost the radio show because management thought we were too favorable to his views.

RN: Were you at the University of Buffalo at this time?

IR: I had left the University.

RN: Then you moved to New York City.

IR: I moved to New York in 1962.

RN: How did your family feel about you moving?

IR: My step-father worked in the auto plant. Chevrolet. My mother was a housewife and saw her highest achievement as working in a sales department, even though she later wrote a book, Black Girl From Tannery Flats, about segregation in Tennessee and her migration to Buffalo. My mother encouraged me, but she had to temper it. My stepfather, since he was born in the South, was semi-literate, and envious of his children—not only me, his stepson, but also the children he had with my mother. He thought I was making a mistake by moving to New York…“If you can’t make it Buffalo, you can’t make it anywhere,” he said. Buffalo was good to him.

RN: Where did you live when you first moved to New York?

IR: I lived on Spring Street. In an apartment that had been vacated by Jack Kerouac. He had moved to Las Vegas.

RN: A coincidence?

IR: That was a coincidence. I came with a friend of mine named Dave Sharpe, an Irish American writer. He was the one who encouraged me to move to New York.

RN: And how did you and Sharpe know each other?

IR: We met in Buffalo. There was a crowd. Italians, Jews, Blacks, bohemians.We liked Beat literature and jazz. We hung out at a place called Laughlin’s in the avant-garde section of Buffalo called Allentown.

RN: So there was an early literary scene in Buffalo?

IR: Absolutely. One of the members was Lucille Clifton. I took her poems to Langston Hughes, that’s how she got published. Her biographers don’t mention that.

RN: What was the neighborhood like around Spring Street?

IR: Ethnic, at that time. Italian Americans who hated blacks. Baldwin covers racism in Greenwich Village in his novel, Another Country.

RN: So not at all bohemian.

IR: No, no, it wasn’t. You had to go uptown and around NYU, that area.

RN: How did Langston Hughes become familiar with your poetry?

IR: From Umbra Magazine, that circle of writers. They knew Langston. We had a poet by the name of Tom Dent, who was working for the NAACP at the time. He knew artists, writers and civil rights leaders. James Meredith and Charlayne Hunter and Martin Luther King’s brother would come to our meetings… we all used to go to Stanley’s on Avenue B at the time. I believe it’s a laundromat now. But that was like the scene, at Stanley’s. William Peace III, someone whom I knew in Buffalo, introduced me to Stanley’s.

RN: Your connections in Buffalo served you well.

IR: Well, my friend Dave Sharpe became like this famous bartender in the Village. He worked at Club 55, where you might run into Gil Evans or Art Blakey. Matter of fact, when I came from Buffalo the first time, for a weekend visit, the first place I went to was a place called Chumley’s, on Bedford, which used to be a speakeasy. There I met Bradley Cunningham who became a legend. Bradley owned the 55 and Bradley’s on University Place. During that first trip, a screenwriter standing at the bar at Chumley’s looked at a play I’d written and liked it. It was called Ethan Booker, about a clash between Muslims and Christians at a historically Black college. This screenwriter was working on a script based on Orwell’s “Homage to Catalonia.” His approval convinced me to move to New York.

Chumley’s had a literary past, Edna St. Vincent Millay and those people. The covers from books of all the artists that drank there were on the wall. By the time I left New York mine was up there too. It’s still there.

RN: After you started to get published in New York, why did you want to leave?

IR: It’s a cut-throat competition to be a token in New York, and people here aren’t so keen on setting up their own institutions. There are exceptions, like the Nuyorican movement or the AUDELCO awards, which awards achievements in Black Theatre. The New York literary establishment has been imposing tokens in literature, theater, and art on us for a century. They still do it.

RN: Yet New York has so much money floating around. Why don’t more people build institutions?

IR: In this town, it’s all about individual achievements. I wrote a piece about racism in New York museums in Arts Magazine. And there was outrage from black painters. They didn’t want me to expose racism in the New York art world because they felt that one of them might get their stuff exhibited. It’s like when Lena Horne went to Hollywood to protest the stereotypical roles being given black actors. The black actors making money for those roles ran her out.

RN: You were messing up their hustle?

IR: Absolutely.

RN: You mentioned Tom Dent. There is a story about Cafe Le Metro, where you intervened when some white guys hassled him…

IR: They didn’t like black male poets coming in there because white women were present… always an issue in the United States. Race mixing. The Metro was on Second Avenue….these guys are hassling Tom. I intervened and was punched by one of the owner’s hired thugs… so we left. Halfway home, I turned around and came back to the Metro and told Walter Lowenfels, my literary collaborator, who was reading that night, that the owner, who hired the thugs, was a fascist, and if he continued reading I would never speak to him again. Then everyone left. That was the end of the Metro as a poetry scene.

The late poet Paul Blackburn and I were invited by the minister at St. Mark’s Church to continue our readings. That was the beginning of the St. Mark’s Poetry Project. They’ve just got around to acknowledging that that’s the way it happened. Chroniclers of the East Village of the 1960s always omit the black and Puerto Rican presence.

RN: In 2012, in the Boston Review, Junot Díaz wrote, mistakenly, that you had clashed with Toni Morrison in the 1980s.

IR: I have a lengthy piece about Toni Morrison in the forthcoming Black Renaissance Noire. She was the second largest patron of my new play The Haunting of Lin Manuel Miranda.

Díaz sent me a letter. A letter of apology—which, by the way, I printed in my new book, Why No Confederate Statues In Mexico. I told him: “You’re just a token. Soon as they get rid of you they’ll get someone else.” I know how this New York thing works.

RN: What was the arts scene in Northern California when you arrived there?

IR: I think San Francisco got the most publicity. When I was around 18 or 19 I went there. I hadn’t read Jack Kerouac, but we all were aware he was saying something that attracted us. We didn’t want a nine-to-five, we didn’t want to follow in the restricted, lack of mobility of my parents. They had their cars, their home, they had a mortgage, kids. We rebelled against that life. Of course I have material objects as well but I don’t worship them.

RN: What was your impression of San Francisco?

IR: They practiced the same kind of tokenism as New York. When you look at photos of participants, it’s a whole bunch of white guys. Amiri Baraka was a token. And Bob Kaufman. The Beats were misogynists and racists with some exceptions like David Meltzer and Michael McClure. Their leader, Jack Kerouac, was a racist, a paranoid anti-Semite, a fascist who supported Spiro Agnew. He embarrassed Allen Ginsberg on nationwide television. Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Ted Joans, and Kaufman were their strongest writers.

The women Beats were good writers—now it’s coming out. But in those days it was very limited—just support the guys, they told them. Allen Ginsberg said it was not his fault that women had not produced any geniuses. So that’s where they were.

I wrote an essay taking on this attitude and pointed to the Naropa Institute, which was run by Allen as an example. I called it the AT&T of the poetry world. Allen was furious. He bawled me out over lunch at a place called Enrico’s on North Beach. But I stood my ground. The late Bob Callahan educated him on the points I was making. Allen, to his credit, changed. That’s why under Anne Waldman, the Naropa program is now one of the most diverse white-run poetry organizations. You can look at Poets & Writers magazine or The American Poetry Review which carry announcements of residencies and conferences and see it’s mostly a white scene with a few tokens included.

To his credit, Amiri Baraka rejected the tokenism, left that whole scene, and published other people. In a magazine called Diplomat, he said “there were others before me,” and, in Freedom Ways, he says the Black Arts Movement came out of Umbra.

RN: I see. And the black arts community in Oakland begins with…

IR: The Black Panthers included theater and musical components. But the classical form of artistic expression in Oakland is blues. Jimmy Cracklin. Ronnie Stewart. Oakland Blues Society. I was Blues Writer Of The Year for a song I did with Cassandra Wilson. Oakland also has a classic literary tradition—Jack London, Joaquin Miller, that sort of thing. In Blues City, I talk about the blues scene and writing scene in Oakland.

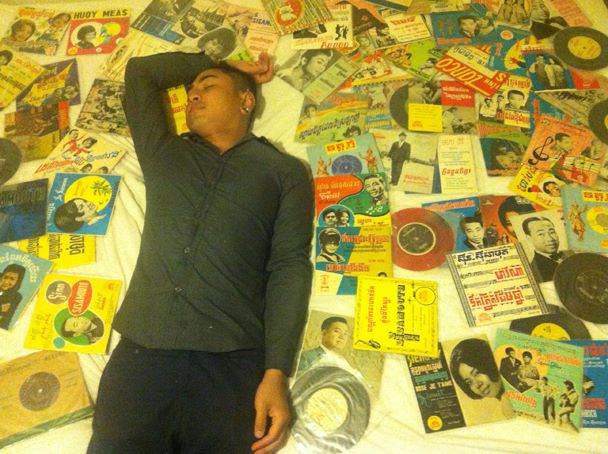

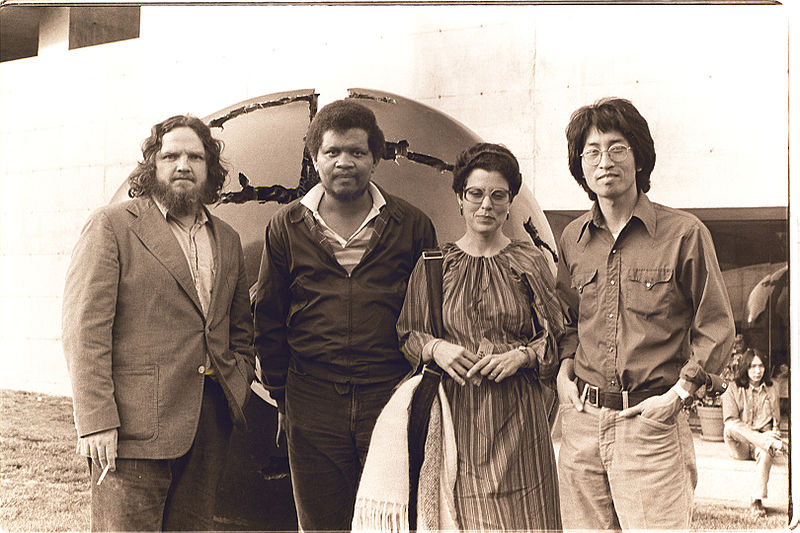

RN: You have a long history of publishing Asian American writers, going back to your early years on the West Coast.

IR: We were among the first, as the Yardbird Collective. I was in Seattle teaching, and I ran across an underground newspaper called the Great Speckled Bird, and read an excerpt of a novel by Frank Chin. It was from Chinese Lady Dies, a long novel he wrote.

I had a contract with Doubleday to do an anthology of black writing—the point was to show that not all black writers write the same way, you can’t just lump them together. (Laughs.) I think it is probably the only anthology that includes a work by Charles Patterson. Patterson was very influential in Black Arts. He’s one of its philosophers.

I had met Victor Cruz. He was 18 years old at the time, a Puerto Rican poet. So I put him in there. Then I put Frank Chin in there. So it made it one of the early multicultural anthologies. So at the Doubleday party for the book, given by Luther Nicholas, in Oakland, the Japanese- and Chinese-American avant-garde met. And that’s the beginning of what some call the Asian American renaissance, because Lawson Inada and Paul Chan met at that party.

Then we started a magazine called Yardbird. Around 1974. And I decided that we would do the third issue dedicated to Asian American writing. And I knew the late Charles Harris, at Howard University Press, and I got him to publish an anthology of Asian American Writing called Aiiieeeee!

RN: I saw a picture of Fay Chiang, maybe taken by you? In the Basement Workshop in the 1970s in New York. Did you and Amiri Baraka read there?

IR: We went down there.

RN: What was your contact with her and that group?

IR: Well, we met Frank and Lawson, and it’s like a chain. Like when we met Leslie Silko and she opened us up to all these Native American writers. When we visited the Basement Workshop the humorous thing was that me and Amiri were the only ones wearing Mao jackets.

RN: You’ve studied Yoruba, Japanese, and, for the newest novel, you studied Hindi. Did you take a class or study online?

IR: I had a tutor. We had weekly lessons using FaceTime. I learned tenses and syntax. I even wrote a poem in Hindi. Tracking down word meanings was tedious, though Google translate was helpful.

RN: In the novel, you include a long list of Hindi words that have entered the English lexicon.

IR: It’s a racist idea that brown and black people can’t get credit for creating the language we use. I learned even some of these well-known German philosophers embezzled Indian traditions. Claimed them as their own. This Aryan hoax, which Nietzsche and others used, for example. We were told in colonial school that English was part of the Indo-European language.They never explained the Indo part. It’s obvious that Sanskrit influenced German and English.

RN: When did you first conceive of Conjugating Hindi?

IR: Just as I used to be the only black person at Asian American literary conferences, I used to be the only black person at the Irish conferences. I told Bob Callahan, the publisher and Renaissance man, who didn’t consider himself white, but Irish, that I have Irish American ancestors. This was according to my grandmother who said that her father was Irish. I began to get invited to Irish American events. And he introduced me to Dan Cassidy and the Irish American Renaissance going on on the West Coast.

I had gone to an Irish conference at the University of California at Berkeley. The Irish Republican politician Gerry Adams, leader of the Sinn Féin party, had brought all these people together: Asian American Studies, Chicano studies, even Angela Davis turned out. Somebody in the room got up and said: “We don’t like Gerry Adams. We’ve made up, and we don’t like what you said about Lord Mountbatten. We apologized to the British for his assassination.”

And I said: “What about his policies in India when he was Viceroy?” And the guy got quiet. I didn’t really know anything much about his role in India, but by the reaction I knew I was on to something. So I went out and read about Mountbatten, and ran across his sexual abuse of Indian boys, which lead me to Churchill’s role in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Indians, and how he sowed conflict between Muslims and Hindus.

RN: What was the inspiration for Shashi Paramara, the super right-wing Indian American character?

IR: I’d noticed an alliance between some Indians and the white right, whether it be at the racist Dartmouth Review or the intelligentsia on the right. There’s a judge of Indian ancestry who is up for a federal judge ship who won’t say whether she supports Brown v. Board of Education.

Some people say the character Shashi is Dinesh D’Souza, who got involved in some sexual scandal, and who just got pardoned. And I’ve had run-ins with Dinesh. He quotes me a lot in his book The End of Racism where he praises slave masters.

But the Shashi character is an assemblage, a pastiche.

RN: What was your personal interaction with Dinesh D’Souza like?

IR: Dinesh D’Souza is being used as a mercenary against us. In order to move ahead on the right, you have to take down black people, it’s part of their initiation. So Andrew Sullivan, for example, a white nationalist who supports gay rights, made his reputation taking down black people. Then he moved into the big time, taking on other issues, like foreign policy. That’s how these neo-cons started, jumping on blacks.

RN: The novel includes references to Khushwant Singh’s History of the Sikhs, as well as a long list of books by South Asian writers, including Bharati Mukherjee, R. K. Narayan, Rafia Zakaria, and Shashi Tharoor.

IR: I’m a fast reader.

RN: Did you have a road map for the story?

IR: No, no. You have to think. You get stuck. Eventually you find a way to move forward.

RN: If you search online for reviews of Conjugating Hindi…

IR: or Juice!

RN: …no reviews in the mainstream press.

IR: Right. They have about four writers, who they are very fond of, and they can’t do a review without mentioning me as their antecedent. It’s all over the place. Yet they won’t review my books.

RN: Several organizations you’ve started work to highlight writers outside the mainstream.

IR: In Oakland we have established foundations as viable as theirs. We do the American Book Awards. They resent that because it rivals the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award, which are all ethno-nationalist and reward the same tokens year after year. The New York literary elite has been imposing tokens on us for a century. Writers, artists, you name it, people with black and brown skin, but who are likely not to be “difficult.”

We have a Board of Directors that’s very impressive, including Juan Fillipe Herrera, former poet laureate of the United States, Marlon James, who got the Booker, and Joy Harjo, the first Native American United States Poet Laureate.

RN: You dedicate the book to the memory of Rose Mukerji. Who was she?

IR: I met my partner, Carla Blank, who I’ve been with for fifty years, doing a multi-media show together on St. Mark’s Place. Carla is a choreographer and dancer who had worked with Rob Wilson and directed a play which toured the Middle East with a Syrian and Palestinian cast. She directed my plays in China. We’ve been together a long time.

Rose, who was also a dancer, was a mentor to Carla. She sympathized more with my wife’s life goals then other people. It would have been okay if my wife had become a ballet dancer… but she became a postmodernist. (Smiles.) Rose studied at Columbia, taught at Brooklyn College and consulted with PBS on children’s programming. She married an Indian intellectual, Prafulla Mukherji, and, after his death, sponsored Indian students to study in the U.S. in his name. She passed away recently. I dedicated the book to her.

RN: Last year, Cornel West in a conversation with Deborah Chasman said: “[S]omething that I am inspired by about Baldwin, Amiri Baraka, Ishmael Reed, Gwendolyn Brooks—they were all darlings of the liberal establishment, and they rejected that status, which meant they were pushed to the margins…” What quality must a writer possess to be able to write like that?

IR: Well, I wasn’t pushed. I left New York—where trends in black culture are manipulated by outsiders—voluntarily. In the West we are able to influence standards. I’ve been able to create more depth in my work in an environment with less distractions and plenty of space.