Khmer record and film collector Nate Hun is part of a growing movement quietly reconstructing Cambodia’s tumultuous past.

April 23, 2015

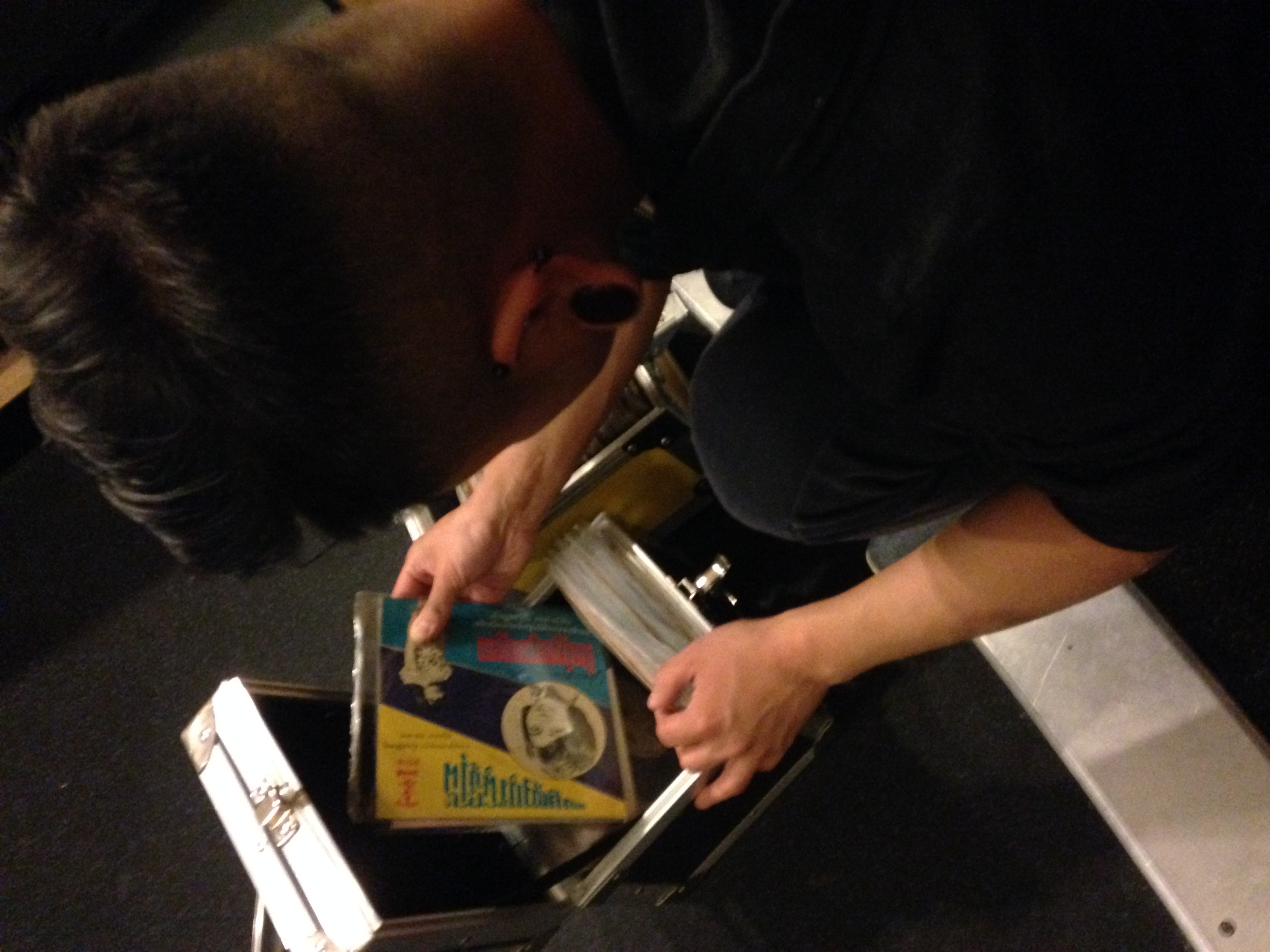

I’m running several minutes late. When I feel the elevator jimmy to a stop and the doors creak open onto WFMU’s fourth floor, I recognize Nate Hun immediately. He’s at a table in the middle of the volunteer room, hunched over a black PC notebook. The sides of his head are shaved close, accentuating his gauged earlobes, which are plugged with black discs the color of record vinyl. At his side are two metal carrying cases.

After Nate and I exchange hellos, a WFMU staffer breaks in with a friendly shout to tell me my second guest has arrived. I excuse myself, leaving Nate to his task — preparing MP3s for our upcoming broadcast — as I head back downstairs to welcome John Pirozzi, whose critically acclaimed documentary, Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock and Roll, opens this week at Film Forum.

John, Nate and I are about to spend the next three hours on the air talking about Cambodian music and history and playing selections from Nate’s sizable digital and vinyl collection.

Collecting Memory

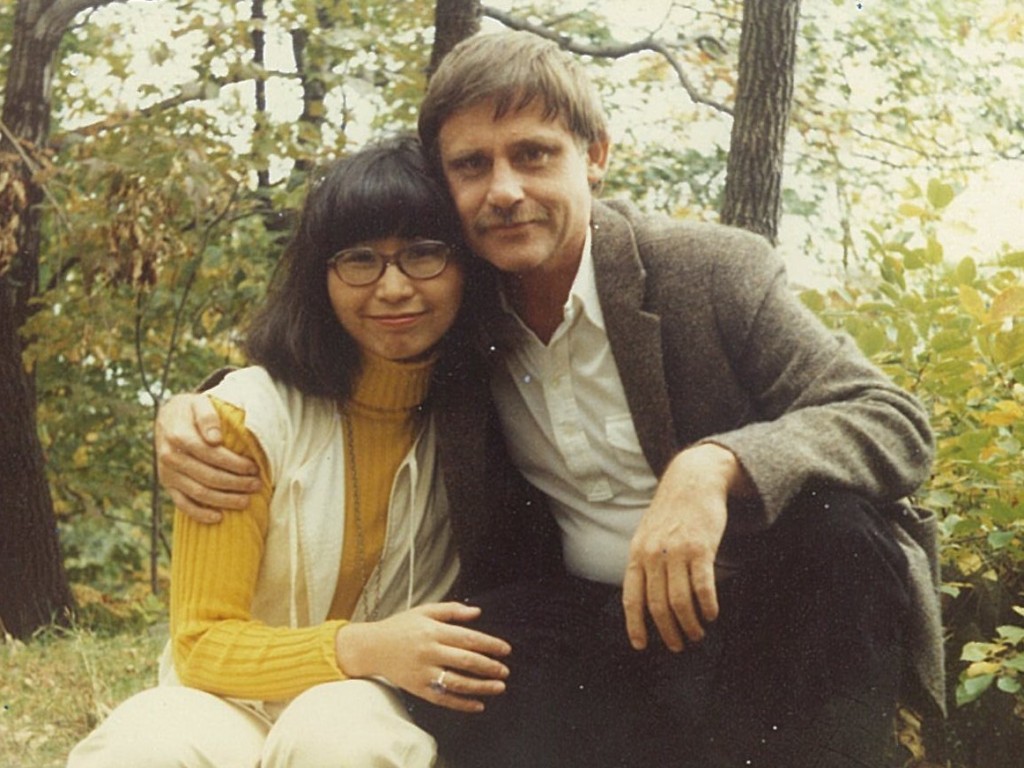

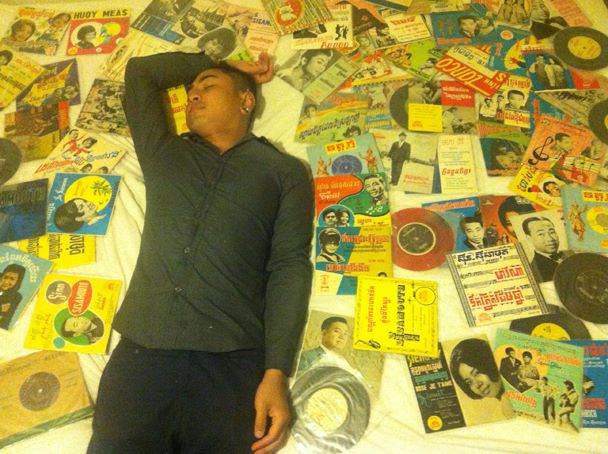

Nate, whose given name is Sovannet, is one of the biggest collectors of sixties and seventies Cambodian pop music on 45rpm records in the country. His parents, both from Cambodia, met in Brooklyn after the fall of the Khmer Rouge opened up immigration to the U.S., but Nate was born and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, where his parents eventually moved to be part of that city’s growing Cambodian population. (Lowell is home to the second-largest community in the country.)

His first recordings were on cassettes and CDs, which he found in Lowell’s Cambodian video stores.

“Cambodian music was often played around the house, but I probably played it more often than my parents,” Nate admits when I ask him how he got into collecting. “I’m not sure what it was that attracted me to this music, but I just kept listening to it and collecting more and more things.” His first recordings were on cassettes and CDs, which he found in Lowell’s Cambodian video stores. He also collected Cambodian films on VHS, a few of which starred some of the singers and musicians he was listening to.

“My interest grew in part because every time I asked my parents or others in the community a question about the music, the answers were really vague. No one seemed to be able to offer more than, ‘Oh, yeah, that music’s great!’”

The specifics about the people who had written, performed and recorded the songs — about what the music and the artists meant in the lives of the pre-Khmer Rouge Cambodians who listened to it — seemed forgotten. John experienced similar frustration when he set out to make his documentary. The film took nearly a decade to complete, in part because the history had to be patched together from interviews with dozens of people scattered all over the globe.

Perhaps forgetting — the good times along with the horrors that followed — was a step toward healing. Nate recalls that the Cambodian Genocide under Pol Pot was rarely discussed by his parents or others in the Lowell community. “I never fully understood the whole concept of what had happened until I became a teenager and started to do research on my own,” he explains.

Nate recalls that the Cambodian Genocide under Pol Pot was rarely discussed by his parents or others in the community.

Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten isn’t the first documentary about Cambodia’s pre-Khmer Rouge creative history that Nate has been involved with. As Nate’s collection grew, he began to look for more information online, discovering filmmaker Vathana Huy’s blog, Golden Age of Khmer Cinema. Vathana, who moved to France in the early eighties, put Nate in contact with Davy (“DAW-vee”) Chou, whose father was a filmmaker. Davy was starting to make a documentary of his own about Cambodia’s pre-Khmer Rouge film history and looking for copies of some of the 400 films believed to still be in existence. Nate owned 30 of them.

It was while collaborating with Davy that Nate was introduced to John. “John was in contact with a few people in Phnom Penh during the time that Davy was there working on the Cambodian film documentary Golden Slumbers and they eventually got in touch with each other. Davy was coming over to the States for the first time, so we planned to meet in New York. When I met Davy in New York, Davy introduced me to John, and John and I just started working together.”

New Masters

“Nate’s a big part of Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten,” John elaborates. “He brought us so much music, music in good shape on the original vinyl, un-remixed, and he did most of the translations for the lyrics. Because the master tapes of these recording were all destroyed, good copies of vinyl records have kind of become the new masters.”

Most Cambodian pop from this era in circulation on CD or cassette has been sonically altered. Some of it has been sped up to fit more tracks on a single side of a cassette; some of it has been recopied so many times that the high frequencies have been muddied out of existence. In the eighties and nineties, a thriving industry in Cambodia, France and the U.S. added drum, synthesizer and other tracks to repackaged recordings of sixties and seventies music to make them sound crisper.

Nate encouraged John, who was planning to use these altered recordings in his film, to hold out for clean, vinyl copies. The two of them, along with Grammy Award-winning audio engineer Michael Graves, collected and worked on the 20 songs, re-mastered from vinyl, that make up the film’s soundtrack album, released by Dust-to-Digital. More than a collection of great music, the soundtrack — which includes more than 30 pages of photographs and John’s liner notes — expands on the history outlined in the film to tell the story of how Cambodian pop evolved over the critical decade-and-a-half from 1960 to 1975.

I marvel at Nate’s collection as he opens the first metal carrier and begins to pull out one 45 record after another to play on air. He owns hundreds of them, all in colorful picture sleeves, some of which are in such pristine shape it’s hard to imagine how they were kept in this condition over the years. During Pol Pot’s reign, anyone found owning these records would have been executed. Most of Cambodia’s artists — including the country’s three biggest singers, Sinn Sisamouth, Pen Ran and Ros Serey Sothea — vanished without a trace, presumed to have been murdered by the Khmer Rouge along with nearly 2 million of their friends, relatives and fellow countrymen.

The recording is gorgeous — stripped down to Malay’s slightly nasally voice backed by an undistorted electric guitar with a whammy bar…

I ask Nate how he found his copy of “Thavery,” an extremely rare single recorded by Sinn Sisamouth in the sixties that we’re about to play. “Through a relative who was going over to visit Cambodia,” he explains. “I had begged and begged and begged him to try and find something for me and he happened to have a relative there who had a few records — not many, but a few — and he was able to convince him to sell the physical records when I promised to make digital copies for him so he’d still have the music.”

John explains that the next project, now that the film has been released, may be to work with other big collectors like Nate — most of whom are in Cambodia, France or the U.S. — to create a single, high-quality digital archive of what survives to preserve the music.

Nate cues up one last 45 as our show comes to a close: Chhoun Malay’s “I’m Not in Love.” We haven’t yet played any of her songs, and she was one of Cambodia’s first female pop singers, making a name for herself in Phnom Penh before Pen Ran or Ros Serey Southea got their starts. She’s also one of few artists who survived the regime, hiding her entertainment past.

Most of Cambodia’s artists — including the country’s three biggest singers, Sinn Sisamouth, Pen Ran and Ros Serey Sothea — vanished without a trace…

The recording is gorgeous — stripped down to Malay’s slightly nasally voice backed by an undistorted electric guitar with a whammy bar, a bass and drum kit, and punctuated by a trumpet, saxophone and two or three male backing vocalists. It shifts from a deceptively up-tempo surf-guitar tremolo opening to a minor key melody not quite like any I’ve heard in western pop. Malay’s voice is so clear that I have the haunting sense of understanding every word, despite the fact that the lyrics are in Khmer, a language I don’t speak.

Hours later, at home, I realize how fortunate I was to see and hear Nate’s copy of “I’m Not in Love.” I’m reading about Chhoun Malay in the book that accompanies the Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten soundtrack. It’s only then that the gravity of everything Cambodia lost — as if the unthinkable number of lives isn’t enough — sinks in:

“…[Malay] is best remembered for her concerts; her recordings, like the work of so many other Cambodian artists, were either lost or destroyed during the Khmer Rouge era.”

[Check out 50 original Cambodian album sleeves and hear Nate Hun DJ from Khmer 45s Thursday, April 23 from 7:00-11:00 PM at the Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten soundtrack release party. And, this weekend, catch six original members of Cambodian rock and roll bands Baksey Cham Krong and Drakkar, with special guests Chhom Nimol of Dengue Fever and Sinn Sisamouth’s grandson Sinn Sethakol, at City Winery in Manhattan or Monty Hall in Jersey City.]