On making critical connections to the long legacies of intraracial and cross-racial Black and Asian American lesbian organizing and community building.

March 25, 2021

Ever since I was a child, I always had this insatiable curiosity for the past. Some of my favorite childhood memories are going to my grandmother’s house and looking through our family photo albums. My grandmother and I would burst into uncontrollable laughter as she shared with me the memories and stories behind those photos. I remember reading my grandmother’s Ebony: Pictorial History of Black America encyclopedias and being in awe of the expansiveness of Black history that was not taught to me during my formative years of education. I remember wanting to touch my grandmother’s fine china tea sets, and her scolding me for even attempting to put my grubby little fingers on her precious heirlooms.

It wasn’t until years later that I realized my curiosity for the past—particularly my family’s past and lineage—would lead me to want to know more about the past lives of others. It would lead me to the archives.

Black feminist scholar Saidiya Hartman in “Venus in Two Acts” (2008) writes about the dangers and violence of white supremacist, patriarchal, and cis-heteronormative revisionist histories in the archives. Throughout history, we have seen how Black, Asian, and other communities of color have been excluded, objectified, exploited, rendered faceless, and nameless in the archives. This exploitation and objectification in the archives directly connects to the contemporary de jure and de facto non-citizenry of Black and Asian communities. It is a reflection of the continuous and heightened anti-Black and anti-Asian state and quotidian violence that impacts our communities domestically and globally.

However, when we interrogate the archives of and by the most marginal in our communities—not as objects or property but as materials written and authored from their own perspectives—what can these archives tell us about the fortitude of Black and Asian American queer women who recognized the urgency and necessity to tell their own stories? What about archives that speak to what scholar Tiffany Florvil examines as a politics of queer belonging, but more specifically a Black and Asian American queer belonging? What about archives that speak to Black and Asian American lesbian self-determination and resistance?

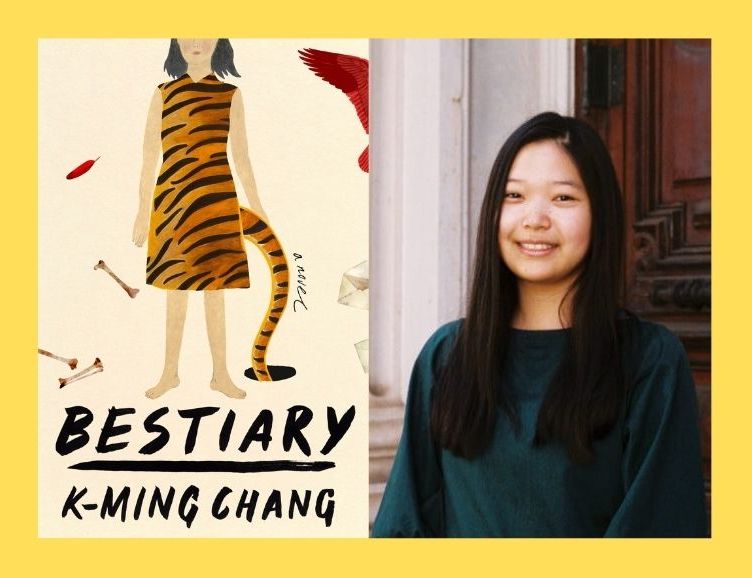

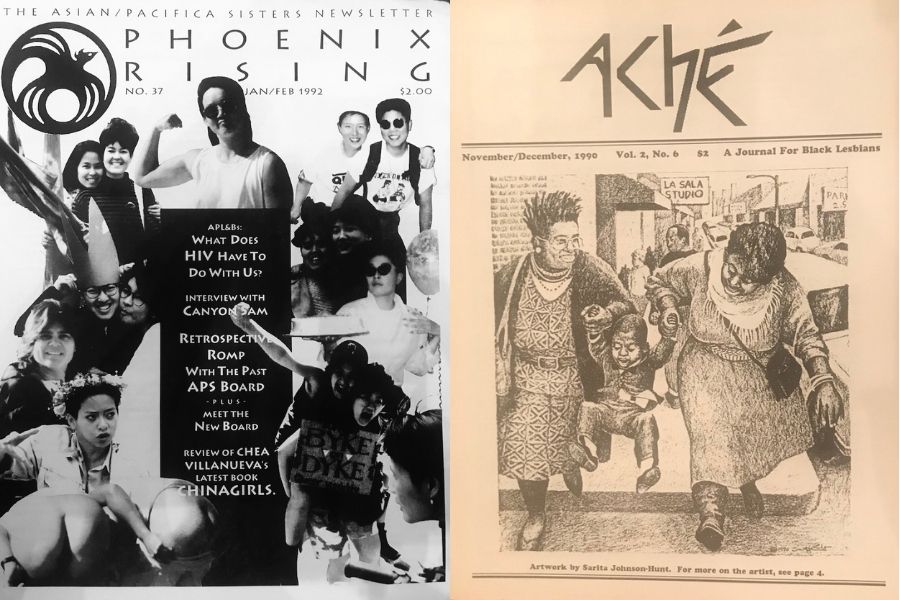

By exploring my personal archives of journals and newsletters published by two organizations formerly based in the San Francisco Bay Area—Phoenix Rising, a newsletter published by the Asian/Pacifica Sisters and Aché: A Journal for Lesbians of African Descent—I saw how these archives offered critical insights on how Black and Asian American lesbians created safe spaces and community for themselves, in spite of ostracization by mainstream society and the communities they belonged to.

Phoenix Rising and Aché also detail how Asian American and Black lesbian women forged lesbian/queer solidarities, networks, and alliances in the United States and in the Asian and African diasporas. Moreover, the archives expose various collaborations and connections among and between individual Black and Asian American lesbians of Phoenix Rising and Aché and their interactions in the Bay Area and beyond.

Phoenix Rising: The Asian/Pacifica Sisters Newsletter

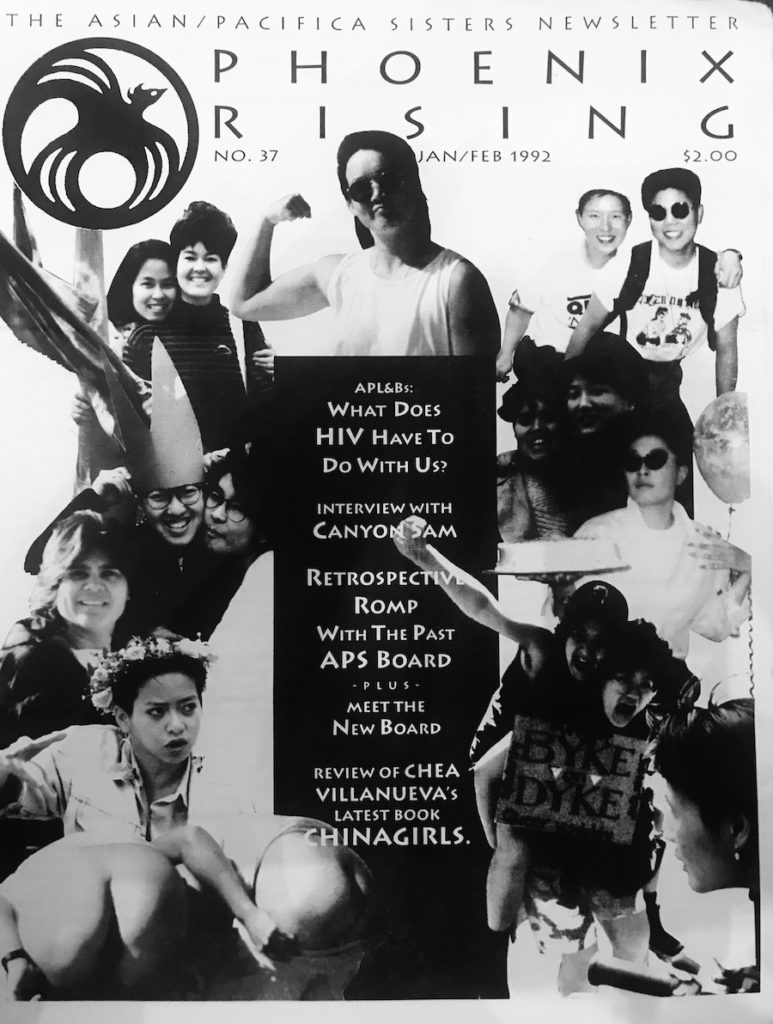

The newsletter Phoenix Rising emerged in 1984 as a space for Asian and Pacific Island lesbians to build bridges and community in the San Francisco Bay Area. The founding editors of Phoenix Rising—considered to be the first Asian American lesbian newsletter in the U.S—included Lori Lai, May Lee, Susan Lee, Pam Nishikawa, Gisele Pohan, Marie Shim, Doreena Wong, and Zee Wong. According to Amy Sueyoshi, author of “Breathing Fire: Remembering Asian Pacific American Activism in Queer History,” the title of the newsletter—Phoenix Rising—“referred to these women’s resilience and beauty, rising out of the ashes that racism, sexism, and homophobia might otherwise leave behind.”

Themes and topics discussed in the newsletter included an advice column for Asian and Pacific Island lesbians titled “Ask Miss Maki;” “coming out” stories; news about Asians and Pacific Island lesbians in the Asian Diaspora; members participating in the Gay Games; intimacy, erotica, and sex; the HIV/AIDS crisis; and more. Phoenix Rising not only curated a space for Asian and Pacific Island bisexual and lesbian women to express pride in themselves and their vibrant community, but it “defied stereotypes of quiet Asian women bound by strict families, immigrant values, and submissiveness.” Multimedia artist Sophia Yuet See is currently building an important archive on the pioneering work and efforts of Phoenix Rising.

In June 1988, the Asian/Pacifica Sisters (A/PS) was formed. The Asian/Pacific Sisters was “one of the earliest and largest grassroots organizations at the intersection of lesbian and Asian.” Ten Asian and Pacific Island women from San Francisco, San Jose, the East Bay, and Napa originally formed A/PS after reading the “Butterflies and Dreams” advertisement in Phoenix Rising, which was a “calling card and starting point to establish and form an organization that would attempt to speak to the needs and concerns of Asian/Pacific lesbians and bisexuals.”

Phoenix Rising and the Asian/Pacific Sisters are a part of a longer legacy of Asian American queer activism and organizing in the Bay Area and across the United States. For example, Crystal Jang, a Chinese American lesbian activist and co-founder of the Asian Pacific Islander Queer Women & Transgender Community (APIQWTC), and Older Asian Sisters in Solidarity (OASIS), started organizing on Asian LGBTQ+ issues during the 1960s and 1970s. Jang “started a petition at the City College of San Francisco, calling for women students on campus to be allowed to wear pants and successfully changed the dress code.” Moreover, in 1978, Jang was an outspoken opponent of the Briggs Initiative, formally known as the California Proposition 6, a ballot proposition authored by conservative state senator John Briggs that would have banned gay and lesbian people from working in schools. Jang was also active with the Asian/Pacific Sisters and the Asian Pacific Lesbian and Bisexual Network (APLBN).

This legacy of queer Asian activism and cross-racial movement building was alive on the east coast as well. From October 12 to 14, 1979, queer Asians from across the U.S. participated in the first National Conference of Third World Lesbians and Gays in Washington, D.C. Hosted by the National Coalition of Black Gays (NCBG), the conference was held at Howard University, a historically Black university, and coincided with the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights that took place on October 14 of that year. Among the organizations who attended the conference were the Combahee River Collective; the Salsa Soul Sisters, the first organization dedicated to lesbians of color in the United States founded in New York City in 1974; the Bay Area Gay Alliance of Latin Americans; and the Lambda of Mexico City.

Asian American lesbian feminist and poet Michiyo Fukaya, who delivered a speech at the conference titled “Living in Asian America: An Asian American Lesbian’s Address Before the Washington Monument.” According to Fukaya, the gathering at the first National Conference of Third World Lesbians and Gays was “the first time in the history of the American hemisphere that Asian American gay men and lesbians joined to form a network of support.”1

Also, in 1979, Nancy Hom, Genny Lim, Canyon Sam, Kitty Tsui, Nellie Wong, and Merle Woo formed the first Asian American women’s performing arts group, Unbound Feet. Tsui, who is the first Chinese-American lesbian to publish a book, Words of a Woman Who Breathe Fire in 1983, is not only a pioneer in the Asian American lesbian movement but was also a member of the Asian/Pacific Sisters and an editor of Phoenix Rising. Unbound Feet co-founders Nellie Wong and Merle Woo both contributed to the feminist anthology, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, published in 1981. In 1983, Nellie Wong was a part of the U.S. Women’s Writers Tour to China, which included renowned Black American authors, Paule Marshall and Alice Walker.

Prior to being an editor of Phoenix Rising, in 1971, Tsui joined Third World Communications, “a media collective comprised of media people, artists, writers, and poets, cultural workers, and community activists.” The media collective published the anthology, Third World Women. The core group of the collective were Asian, Black, and other women of color artists, educators, and activists including Janice Mirikitani, Diana Lin, Nina Serrano, Thulani Nkabinde (now Thulani Davis), Geraldine Kutaka, Avotcja Jiltonilro, Penny Williams, Jessica Hagedorn, and Ntozake Shange, who is best known for her award-winning choreopoem “For Colored Girls.” Multiracial collectives that emerged during the second wave of feminism such as Third World Communications and the Bay Area chapter of Third World Women’s Alliance sought to challenge one-dimensional and exclusionary stances within feminist theory, as well as sexism within male-led movements from intersectional, anti-imperialist, and class-conscious perspectives.

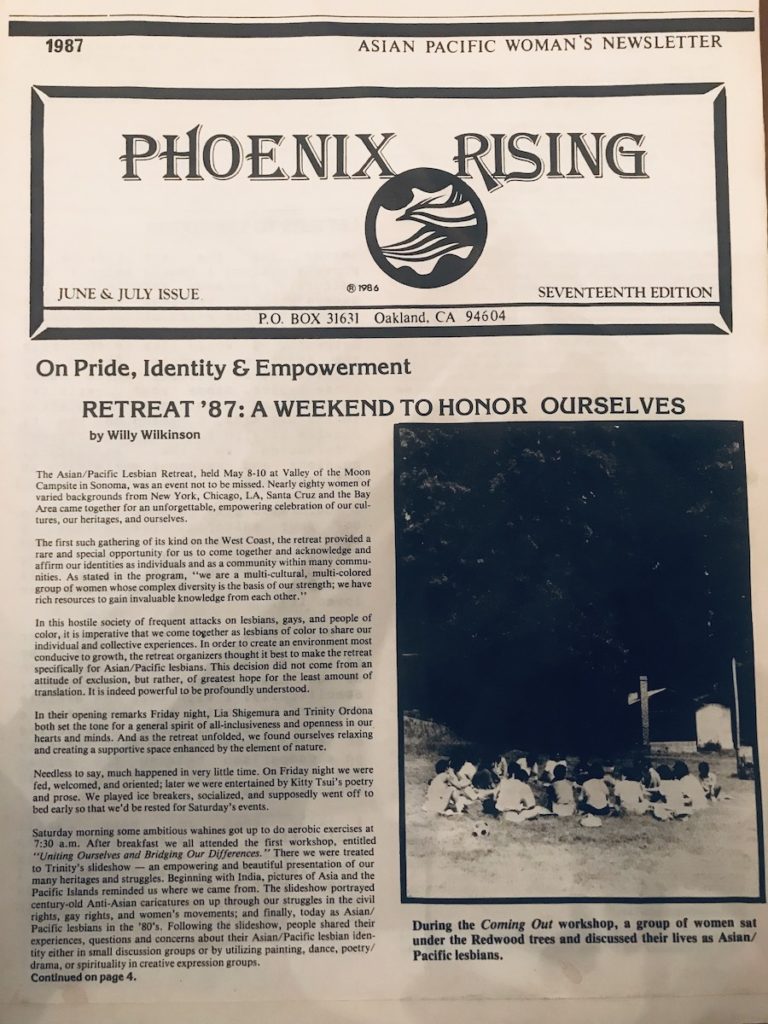

In the June/July 1987 issue of Phoenix Rising, Tsui remarked on the Asian/Pacific Lesbian Retreat that took place from May 8 to 10, 1987 at the Valley of the Moon Campsite in Sonoma County, California. According to the newsletter, this meeting was one of the first of its kind—almost eighty women from New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Santa Cruz, and the Bay Area congregated to find comfort and community as Asian and Pacific Island lesbians. The retreat was dedicated in honor and in memory of Anita Oñang, Tsui’s best friend. In “Breaking Silence, Making Waves, and Loving Ourselves: The Politics of Coming Out and Coming Home”, Tsui revealed that Oñang passed away from cancer in spring 1986. In “An Open Letter to All of the Retreat Participants” published in Phoenix Rising, Tsui shared how the retreat was a transformative experience for her: “The weekend was a very affirming one for me for a number of reasons. When I first came out as a lesbian thirteen years ago, I thought I was the only Asian Lesbian in the world. It was very uplifting to look around our circle and see so many women of all ages and backgrounds together in one place.”

Willy Wilkinson, a prominent LGBTQ+ activist and documentarian of early Asian American queer and trans movements, also wrote about the Asian/Pacific Lesbian Retreat at Sonoma Valley, that was published in the July 1987 issue of Coming Up: The Gay/Lesbian Newspaper and Calendar Events for the Bay Area. Citing Caribbean American lesbian poet Audre Lorde, Wilkinson wrote on the importance of Asian lesbians sharing their individual and collective experiences as a way to empower and encourage themselves:

“This retreat was organized in two-and-a-half months, driven by a sense of urgency that we needed to give this to ourselves; we needed it the day before yesterday. As Audre Lorde writes in “Eye to Eye: Black Women, Hatred, and Anger,” “self-empowerment is the most deeply political work there is, and the most difficult.” The idea of organizing this retreat specifically for Asian/Pacific lesbians did not come from an attitude of exclusion, but rather, of hope for the least amount of translation.”

Wilkinson was also an editor of Phoenix Rising and he is the “first Asian and first transgender community health outreach worker providing street-based HIV education and crisis intervention for sex workers and drug users in San Francisco.”

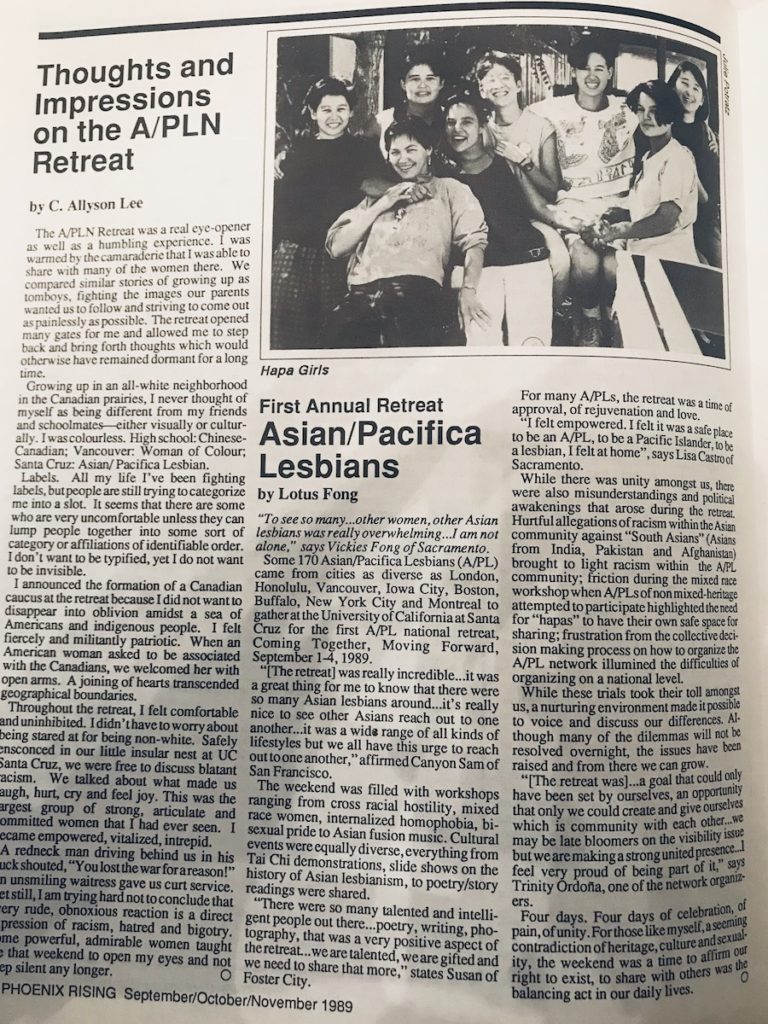

The 30th edition issue of Phoenix Rising, published in 1989, reviewed events from the second Asian/Pacific Lesbian Retreat (which was the first national Asian/Pacific Lesbian retreat) at the University of California, Santa Cruz from September 1 to 4, 1989. The theme of the retreat was “Coming Together, Moving Forward.” Over 175 bisexual and lesbian women of Bangladeshi, Chinese, Fijian, Filipino, Guamanian, Hawaiian, Indian, Indonesian, Japanese, Korean, Malaysian, Pakistani, Singaporean, Sri Lankan, Vietnamese, and other Asian backgrounds attended the conference. Workshops and discussions that took place during the four-day conference included the importance of documenting and archiving Asian/Pacific lesbian histories; internalized homophobia; and bisexual and lesbian safe sex and the AIDS crisis. However, there were tensions and criticisms that arose during the conference, especially when South Asian lesbians from India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan raised concerns and brought attention to racism within the Asian/Pacific lesbian community.

V.K. Aruna (who was one of the South Asian organizers of the “Coming Together, Moving Forward” retreat) wrote about how she and other South Asian lesbian women felt ostracized and overlooked during the retreat. Her critique was featured in the August/September/October 1990 issue of Phoenix Rising and was actually reprinted from Shamakami, a newsletter and forum for South Asian lesbians and bisexuals created to overcome the erasure and exclusion of their voices. The first issue of Shamakami titled, “Identifying Ourselves,” was published in June 1990.2 Criticisms by South Asian lesbians apparently urged a new editorial direction of Phoenix Rising, as the featured story of the 1993 issue was with Indian activist and writer Pratibha Parmar. The interview coincided with the release of Parmar’s 1993 award-winning documentary about female gential mutilation, Warrior Marks, which was executively produced by bisexual writer and activist Alice Walker, who in 1983 became the first Black woman to receive the Pulitzer Prize for Literature for her book, The Color People. The film would later be published as a book with the same title.

Members of the Asian/Pacifica Sisters also organized and participated in the “Dynamics of Color Conference” that took place November 11 to 12, 1989 at Mission High School in San Francisco. The purpose and goal of the conference was to provide lesbians of all racial backgrounds “tools to combat racism, and focused on addressing racism on three levels: individual, group, and political/theoretical.” However, lesbians of color were prioritized at the conference and given the opportunity to share their voices, concerns, and perspectives on racism “instead of the common racial dynamic that usually “allows” white lesbians to dominate group discussions.” The keynote speaker of the conference was Barbara Smith, founding member of the Combahee River Collective and co-founder of Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press with Audre Lorde. During her speech, Smith highlighted the importance of lesbians of color coming together and learning from another. Moreover, Smith reiterated the need for lesbians of color to build solidarities with organizations and collectives of various races, backgrounds, sexualities, ages, and identities.

Many members of the Asian/Pacifica Sisters and networks of queer Asians from across the country also participated in the 1993 March on Washington For Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation. Urvashi Vaid, an Indian LGBTQ+ activist, lawyer, and former executive director of the National LGBTQ+ Task Force, spoke at the march. On February 26, 1994, the Asian/Pacific Sisters and the Gay Asian Pacific Alliance (GAPA) marched in the Chinese New Year Parade in San Francisco. Joined by over 100 Asian and Pacific Islander bisexuals, lesbians, and gay men, who shouted “we’re queer; we’re Asian; and we’re all across the nation,” the Spring/Summer 1994 issue of Phoenix Rising detailed events of the historic gathering; as it was first time in the U.S. that queer Asians participated in the Chinese New Year Parade in the city.

Aché: A Journal for Lesbians of African Descent

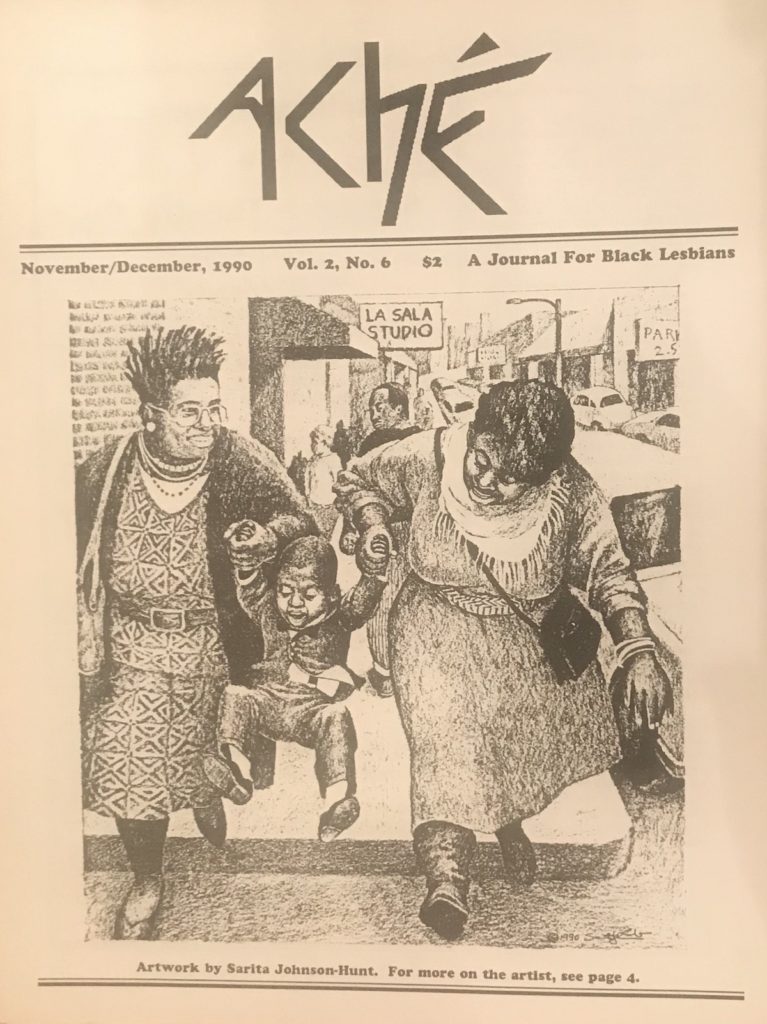

Co-founded in 1989 by archivist and activist Lisbet Tellefesen and storyteller and performance artist Pippa Fleming, Aché—which was also known as “The Bay Area’s Journal for Black Lesbians”—was a free “monthly journal by Black lesbians for the benefit of all Black lesbians.” The journal was dedicated in memory of Black lesbian-feminist, poet, and activist Pat Parker, who passed away from breast cancer in 1989.

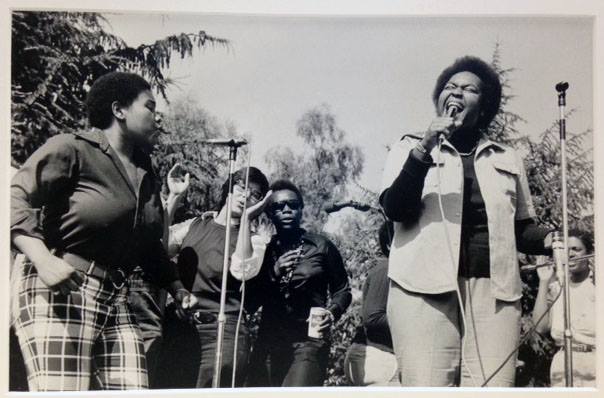

In making connections to Black and Asian American lesbian community interactions, movement building, and even romantic relationships during that time period, a black-and-white photo titled “Gente Gospeliers” taken by lesbian photographer Cathy Cade in 1975 in Oakland, shows Parker standing next to Anita Oñang. Earlier in this article, I mentioned that Oñang was the best friend of Kitty Tsui. Oñang was also a member of the Women’s Press Collective (originally called the Oakland Women’s Press Collective), described as “a foundational entity founded by a group of activist, artistic, and multi-cultural dykes, who were also friends, lovers and ex-lovers [who] occupied the basement of A Woman’s Place Bookstore, publishing and distributing what would become some of the most influential publications of that time by some of the most innovative authors, many of them also members of the collective.” A photo of Oñang appears on the cover of Lesbians Speak Out, which was published by the Women’s Press Collective in 1974. Parker was one of the founders of the Women’s Press Collective. One of Parker’s well-known poems, “For Willyce” is about making love to Women’s Press collective member and poet Willyce Kim, who is recognized as the first Asian American lesbian writer to be published in the United States, with the self-publication of her poetry chapbook, Curtains of Life, in 1970. Her poetry collection, Eating Artichokes, was published by Women’s Press Collective in 1972. Kim’s work was also featured in Phoenix Rising.

The name of the journal—Aché—derives from a Nigerian and more specifically, Yoruba spiritual and philosophical concept (also written as Ase or ashe) which centers on the life force, energy, and power that is able to produce change. With members of Aché acknowledging how they “experience the power of Black lesbianism on a daily basis,” the goals of Aché were as follows: (1) “To celebrate ourselves, our communities, and our accomplishments; (2) to document Black lesbian herstory and culture; (3) to provide a forum where issues impacting our communities can be openly discussed and analyzed; (4) to keep Black lesbians in touch with each other’s activities locally, nationally, and globally; (5) to provide a place where Black visual artists and writers can develop and display their skills; and (6) to help organize and empower ourselves; so that we may become more effective allies in the struggle to end the oppression that we, as Black people, women and members of the gay community, face daily.”

Two years prior to the formation of Aché, the Nia Collective, a transgenerational organization created by and for lesbians of African descent, was established during the Black Lesbian Caucus at the Lesbian of Color conference in San Francisco in 1987. Aché was also an extension of the legacy of the Black Lesbian Newsletter, later known as Onyx, which was published in San Francisco and Berkeley from 1982 to 1984.

Birthed out of a dire need for Black lesbians to have a space where their specific needs and perspectives were addressed and met, Aché had the distinction of being the longest-running journal for Black American lesbians, with twenty-seven issues of the journal published from 1989 to 1995. According to the Black Lesbian Archives (which is hosting a virtual exhibit on Aché from February 20th to March 28th, 2021) an archive founded and created by Krü Maekdo, it was February 1989 when Aché was first published. What started off as Tellefesen and Fleming writing a newsletter for friends and colleagues in the local Bay Area turned into a global network and community of Black lesbians across the African Diaspora, with connections with lesbians of African descent in Barbados, Canada, England, France, Germany, Ghana, St. Croix, South Africa, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and more.

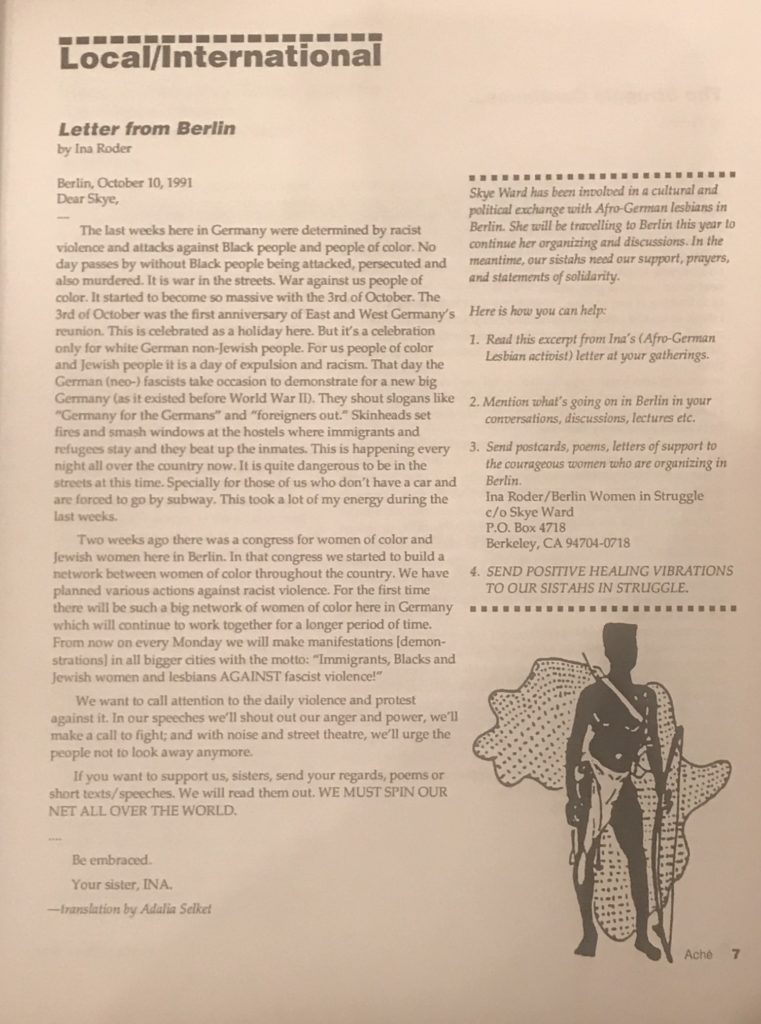

For example, Aché’s February/March 1992 issue features a letter from Afro-German activist Ina Röder-Sissak (in the journal written as Ina Roder), dated October 10, 1991. Röder-Sissako’s letter was addressed to Skye Ward, an Aché board member who was involved in organizing a cultural and political exchange between members of Aché and Afro-German lesbians in Berlin. Röder-Sissako shared details about the sustained anti-Black and racist violence against Black people and people of color in Germany. She also discussed how a network of women of color had come together to repudiate the violent attacks and wrote that “from now on every Monday, we will make manifestations [demonstrations] in all bigger cities with the motto: ‘Immigrants, Blacks, and Jewish women and lesbians against FASCIST violence!’ Moreover, Röder-Sissako asked members of Aché to send poems and letters of support in solidarity with the network of women of color organizing in Berlin. Yvonne Kettels, an Afro-German lesbian activist and visual artist from Berlin who later moved to the Bay Area, and Ika Hügel Marshall, also an Afro-German lesbian activist and author of Invisible Woman: Growing Up Black in Germany, had their essays and creative works published in Aché.

Audre Lorde, the self-described “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” who was a key figure in spearheading the Afro-German women’s movement, also wrote a letter to the women of Aché, while living in St. Croix with her partner, Black feminist activist and scholar Dr. Gloria I. Joseph. Lorde’s letter, dated November 30, 1989, was published in the February 1990 journal of Aché. Sharing how she and Joseph survived Hurricane Hugo and the resiliency of Black, Hispanic, and low-income Crucian people who survived the devastation of the hurricane, Lorde also thanked the women of Aché for sending supplies. However, instead of sending more supplies directly to her and Joseph, in the letter Lorde kindly asked Aché to make a contribution to Sojourner Sisters, Inc., a non-profit organization co-founded by Black Crucian women activists and educators including Joseph, Cassandra Dunn, Elaine Gomes, Janasee Sinclair, and Georgette Norman. At the end of her letter, Lorde wrote:

“The existence of Aché is a deep and satisfying joy to me. It is important that we encourage and support an organ of communication exploring the potentials of Black Lesbian communities. I have seen Aché grow and develop through the hard work of a few committed sisters, and I hope to see even more of our communities and their concerns represented in the future.”

The November/December 1990 issue of Aché documented I Am Your Sister: Forging Global Connections Across Differences, a four-day conference in honor of Lorde that was held in Boston, Massachusetts from October 5 to 8, 1990. More than 1,200 people from twenty-three countries attended the conference and explored the intersections of race, class, gender, sexuality, and difference through Lorde’s work. Reatha Fowler, who attended the conference and wrote about her experience in Aché, recalled how Asian women took to the podium to express their grievances of being stereotyped, overlooked, and discriminated against in society:

“The remainder of the morning was given to women who felt that their voices were not heard. The Asian women were the first to approach the stage. They comprised a group of twelve women, various skin hues from cream to brown and countries of origin. They read a poem together and then one-by-one approached the microphone sharing their pain, anger, and joy to the women sitting tensely in the pews. Some of us holding back our tears, others letting them fall freely, but all of us moved. They spoke so deeply from their hearts of their indoctrination to be silent. They wanted to break through our ignorance.”

“Some of the quotes I was able to dictate through feelings of numbness may give you some idea of the intensity of their pain: ‘I am not your Oriental ornament to be placed on some narrow shelf in your mind.’ ‘Stop telling me to speak English the right way.’ ‘You see beauty only in my exoticism.’ ‘I’m not your little Indian doll.’ ‘Stop telling me to give up my sexist culture. Who are you to tell me what sexism means to me.’ The women left the stage free of some tension with the realization they were clearly heard.”

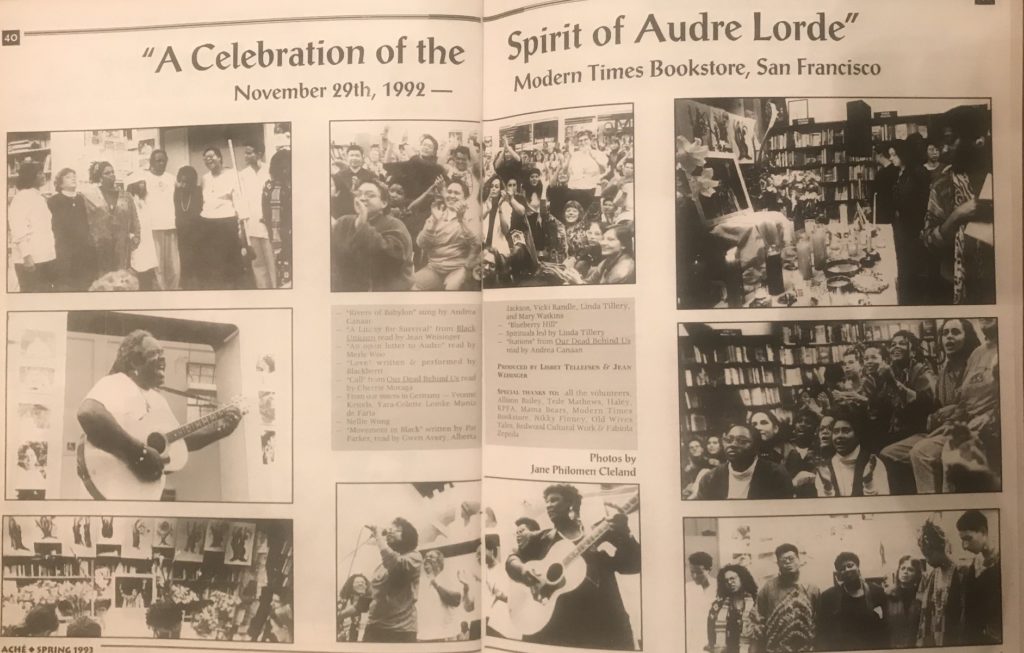

When Lorde passed away from liver cancer on November 17, 1992, Aché dedicated its Spring 1993 issue to her life and legacy. The journal featured an obituary for Lorde written by Barbara Smith. On November 29th of that same year, Aché held the memorial, “A Celebration of the Spirit of Audre Lorde” at Modern Times Bookstore in San Francisco, where Kettels and fellow Afro-German activist Yara-Colette Lemke Muñiz de Faria presented a eulogy for Lorde. Merle Woo (who I mentioned earlier in this essay was a co-founder of the first Asian American women’s performing arts group, Unbound Feet) also spoke at the memorial.3

Aché featured artistry, poetry, and writing of more than 200 writers and visual artists including works by poet and writer Storme Webber, who, according to the February 1990 issue of Aché, participated in “Becoming Visible—The First Black Lesbian Conference”, which took place at the Women’s Building in San Francisco in 1980; Lenn Keller, founder of the Bay Area Lesbian Archives; artist Jackie Hill; and countless others. In 1992, Aché became a non-profit organization, changed its name to the Aché Project, and established a storefront office space on Shattuck Avenue in Berkeley, California, which was located right next to a former office of the Black Panther Party.

While the organization disbanded in 1995 and the editors and contributors of the journal continued to excel in their personal and professional pursuits post-Aché, the Aché archives are critical to understanding the historical emergence, genesis, and expansion of Black lesbian thought, behavior, desire, and belonging. Themes and topics of the journal spanned the gamut—from homophobia in the Black community; creative, fiction, and non-fiction writing and essays; healthcare; African religiosity and spirituality; and a calendar of events about Black and women of color lesbians in the Bay area and transnationally.

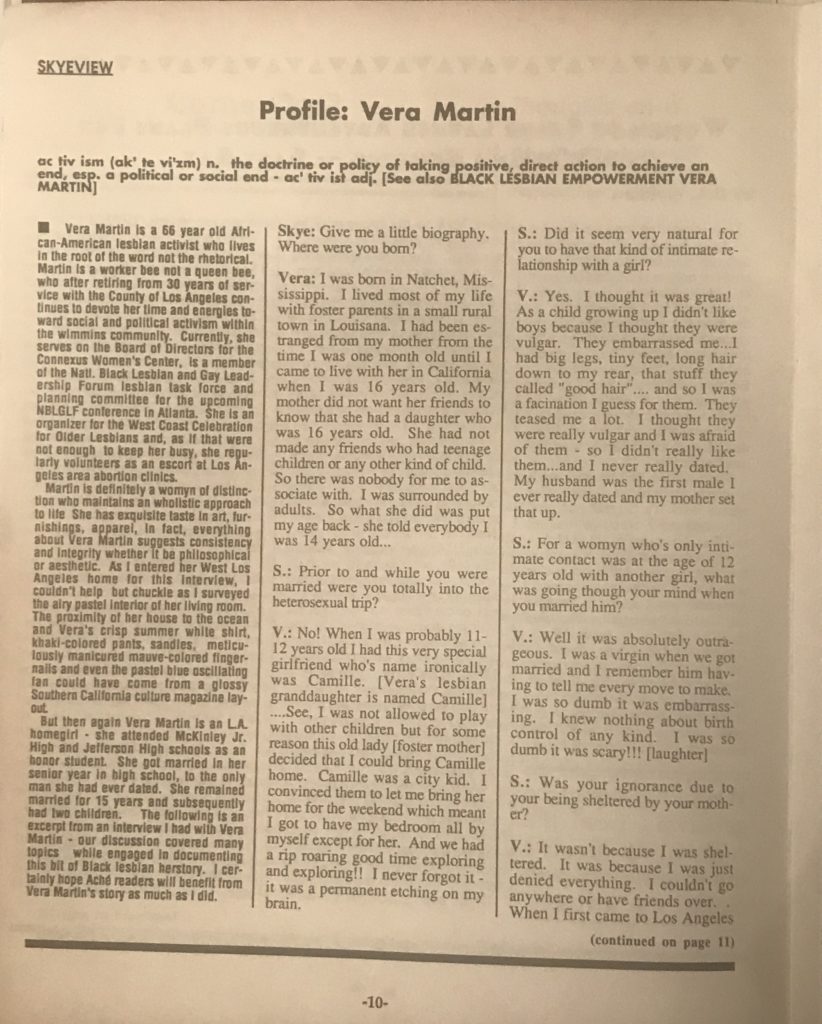

Intergenerational conversations with Black lesbian elders and activists of all ages and occupations was a key feature of the journal. The September 1989 issue featured an interview with Vera Martin, who at the time of the interview was a 66-year old Black lesbian activist, who served on countless boards and initiatives including the National Black Gay and Lesbian Leadesrhip Forum, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Urban League, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, and more. Other activists, artists, educators, and organizers interviewed included poet and musician Avotcja Jiltonilro; author, poet, and playwright, Jewelle Gomez; and former health editor and executive editor of Essence magazine, Linda Villarosa. Earlier in this essay I mentioned Jiltonilro, as she and Kitty Tsui, an editor of Phoenix Rising, were a part of the media collective Third World Communications and who both, in more recent years, have performed on the same stage together.

The journal also had a monthly forum, “On The Table,” where Black lesbians were able to respond to various topics. A question that was posed in the 1989 issue of question posed was: “What are your experiences being accepted or not accepted as a lesbian in the Black community?” Whereas several lesbian women offered their responses to the question, one in particular stated: “I am a Black lesbian MD living in [San Francisco]. Composing this essay allowed me to focus on and express many personal experiences with Black sexist homophobia. Breaking silence, telling what I felt is a therapeutic, strengthening, and healing process. I am convinced that what I’ve gone through has been common to many Black lesbians’ lives. Not one of us is alone.”

Learning from the Archives

This brief overview of Phoenix Rising and Aché does not fully showcase the radical and seminal work these organizations did to build and instill pride, catalyze community, and create visibility for Asian American and Black lesbians in the Bay Area, across the United States, and in their respective diasporas. The archives of these organizations and journals still have much to be explored, and the connections and community forged inside and outside of their networks is also a much-needed site of investigation. While I showcased some examples of cross-racial Black and Asian American lesbian and queer interactions and ties, these examples do not suggest a utopian and/or automatic relationships between Black and Asian American lesbians. Even within their own organizations and newsletters, Phoenix Rising and Aché documented some of the tensions that existed among and between their members, in their communities, and in society.

So, what can we learn from the archives of Phoenix Rising and Aché?

That community matters. That building intraracial and cross-racial movement building and solidarities matter. That self-determination matters. That tension, naming discomfort, and humility in struggle matter. That centering the most marginalized in our communities matters. That resisting white supremacist, cis-heteronormative, and patriarchal revisionist histories matters. That telling, archiving, and preserving our stories matters.

1 Fukaya’s poetry was also featured in Azalea: A Magazine by Third World Lesbians, a periodical for Black, Latina, Asian, and Native American lesbians published by the Salsa Soul Sisters/Third World Wimmin Inc Collective.

2 Prior to Shamakami was Anamika, which is considered to be the first South Asian lesbian newsletter. The creators of Anamika, Utsa and Kayal, who were based in Brooklyn, New York, spoke with Susan Heske about the plight of South Asian lesbians and a transcription of their interview titled “There Are, Always Have Been, and Always Will Be Lesbians in India,” was published in Conditions, a lesbian feminist literary magazine in 1986. Trikone was another South Asian gay newsletter and organization established in San Francisco in 1986 by activists Arvind Kumar and Suvir Das.

3 In 1985, Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press published Apartheid U.S.A. by Audre Lorde and Our Common Enemy, Our Common Cause: Freedom Organizing in the Eighties by Merle Woo, where “an African-American and an Asian American poet make the connections between South African apartheid and North American racism.” Lorde and Woo’s essays were a part of Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press’ “The Freedom Organizing Pamphlet Series,” which “presents issues, strategies, and resources which focus upon the political concerns of women of color.”