“I was interested in a coming-of-age story that wasn’t about running away from the domestic space but about burrowing and binding and rooting more deeply.”

September 30, 2020

In the spring of this year, shortly after the shelter-in-place orders were issued, K-Ming Chang and I began our email correspondence. Like many, I was spending most of my time at home. Her emails were portals to the outside world. She answered each set of questions swiftly, with depth, intelligence, and a sense of humor. Her responses, as richly layered as her work, often inspired more questions. Our conversation was a balm. For a writer living through the terror and uncertainty of a global pandemic, in close proximity to the wildfires ravaging the American West, to correspond with a brilliant, young writer like Chang was to glimpse the possibility of a beautiful future.

At a moment when many Americans love Ta-Nehisi Coates but have never read James Baldwin and others watch films like Crazy Rich Asians and Raise the Red Lantern without any inkling that they were born of books, it’s a delight to encounter a young writer who both knows her history and pays homage to her literary predecessors. Chang doesn’t just acknowledge the past, she speaks to it, she asks it questions. This past transcends boundaries of nation, generation, and self, and by speaking to it, she helps keep it alive. While I don’t want to use the wunderkind narrative as a reductive frame, there’s no denying Chang’s youth makes her keen awareness and broad vision even more remarkable. She modestly attributes the complexity of her perspective to having grown up in a multi-generational household.

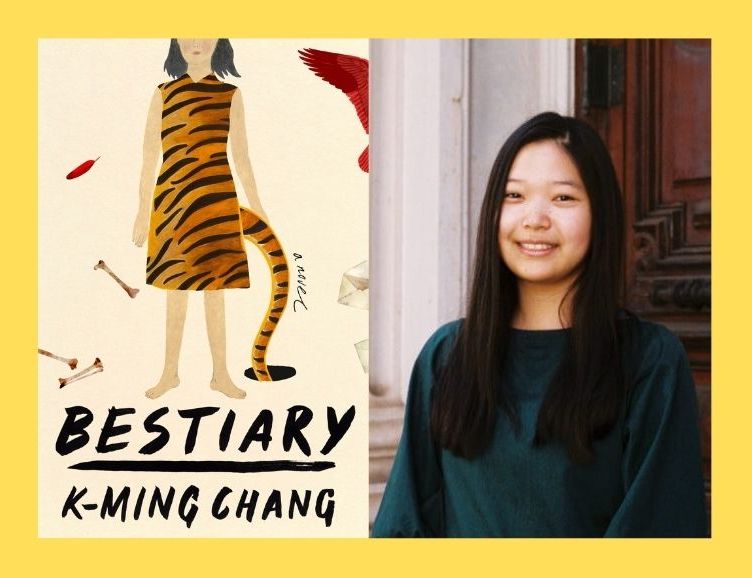

A Kundiman fellow born in 1998 and raised in California, Chang has published poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. Her poetry collection, Past Lives, Future Bodies, was a Lambda Literary Award finalist and her prose has appeared on a rich diversity of platforms including Apogee Journal, Cosmonauts Avenue, Foglifter Press, Kweli Journal, Sinister Wisdom, and wildness. Her chapbook, Bone House, “a queer Taiwanese micro-retelling of Wuthering Heights,” is forthcoming from Bull City Press. When we talked about how much she loves the cover of her debut novel, Bestiary, Chang confessed, “at first I was worried it might be too ‘girly’ and then I realized that that was ridiculous. I wrote this book to be girly—to be girl-centric and feminine and strange.”

Told by many voices, Bestiary is a queer, transnational fairy tale whose irresistible heroine is a Taiwanese American baby dyke. Written in a prose style as inventive and astonishing as the story it tells, to read it is to enter a world where the female body possesses enormous power, where the borders between generations are porous and shifting. A worthy heir to Maxine Hong Kingston, Lois-Ann Yamanaka, and Jamaica Kincaid, K-Ming Chang is a woman warrior for the 21st century—part oracle, part witness, all heart. It is my utter privilege and pleasure to introduce to you, the future of literature, K-Ming Chang.

—Jennifer Tseng

Jennifer Tseng

One of the many wonderful things about Bestiary is its queerness. Where might you place it on the map of queer literature? And are there any queer novels you’d like to recommend to our readers?

K-Ming Chang

I was interested in exploring a narrative where queerness comes from within the family. Bestiary’s queerness was propelled by curiosity. What if? What don’t I know? Why do I assume I’’m alone? I wanted to completely queer the lineage of this family, to think about how queerness, for Daughter, is a chance to create a new lineage and new myths for herself. The mother and grandmother both treat marriage as utilitarian, men as vehicles for their desires. Daughter is plotting a different way of relating to her desires and channeling them.

One of the books that entirely changed me was Trash by Dorothy Allison, especially the story, “River of Names.” It’s about storytelling, intergenerational trauma, and lesbian intimacy, everything I’d always wanted to write about. For a long time I didn’t know it was possible to write about family and queerness in the same space. When I was in high school I read Justin Torres’ We the Animals and was viscerally moved by the way domestic spaces were full of love, violence, hardness, and tenderness. Larissa Lai’s Salt Fish Girl, with its startling and sensory atmosphere, was another huge influence. Lai showed me it was possible to write queer speculative stories.

In Bestiary, there’s a section called “Parable of the Pirate” with a kind of queer origin myth about two exiled pirates—both of whom are seen as “other” by the Qing Dynasty, as outside of Chinese “civilization”— who find homelands in each other. They’re living at sea because they were legally banned from living on land, on Chinese territory, and similarly, their queerness means that they have to forge and occupy a different space. Incredibly innovative, they seek alternative modes of living and existing. They redefine how to conceive of home, nationhood, family, and belonging, in a queer, anti-colonial way.

JT

The way you allow for porosity between generations is very moving. Rather than replicate familiar tropes about generational conflict, you offer new ways of thinking about how young and old might relate to and influence one another. Was this something you set out to do?

KMC

I’m so glad you mentioned the porosity! The vocabulary and the voices of all three generations borrow from, and blend with, each other. I wanted them to overlap, so certain words, images, and syntaxes are shared among all three of the women. I carried this to the last paragraph of the book, where the narrator’s voice mimics the structure of her grandmother’s. By the end, she’s absorbed her grandmother’s fractured syntax, and uses it not only as a product of historical trauma but as a way to see beauty as well.

I wanted to reverse the traditional narrative in which the older members of the family are seen to be inherently repressive, while the younger members must shed this “repression” in order to liberate themselves. Instead, my character excavates her sexuality, her history, her future, the world’s possibilities, by delving deeply into her many lineages.

JT

Bestiary also pushes against the old story of the daughter being expelled from her home and handed over to her husband’s family. Instead it grants women of all generations agency and power. Women are carriers of their own knowledge and experience rather than commodities to be traded.

KMC

Yes, I love that so much! I wanted to subvert that old story of being given away. I remember my mother telling me about a tradition in Jiangsu province, where her father was from. Whenever a daughter was born, the family planted a camphor tree in front of their house so that the matchmaker in the village could see. When the matchmaker walked by the house and saw that the camphor tree had matured to a certain width and height, she knew that the daughter was old enough to be married off. Then they cut down the tree to make a wooden trunk so that the girl could pack her things inside it and leave for her husband’s home. They were called “daughter trees.”

I found this both poetic and painful. There was a practicality to this (it’s strangely genius to be able to walk down a street and know, just from glancing at a tree, what stage of “growth” the daughter is at without visiting the houses), but at the same time, it seemed so violent that the daughter-tree was cut down, that its only purpose was to be cut down—and that similarly, the only reason to monitor a daughter’s growth was for marriage. The daughter tree was like a doubled body, growing outside while she grew inside, planted at the time of birth—a twin of sorts. I thought it was sad that both were given away, that the tree became the container for all the things she had to carry with her. So I decided to write about the daughter-trees in relation to leaving, and how the mother’s daughter tree refused to grow. Her daughter-tree defies this cycle and decides not to mature. I wanted to give agency to that tree, while thinking of its fate as entwined with the mother’s.

I was interested in a coming-of-age story that wasn’t about running away from the domestic space but about burrowing and binding and rooting more deeply. This wasn’t a conscious choice, but I grew up in a multi-generational household, so I had many, many mothers. My grandmother used to call out “Meimei!” and both my mother and I would turn our heads. It was always a moment of whiplash for me—I would stare at my mother, completely bewildered for a second. These moments revealed a symmetry between us, a porousness and sameness. The three of us had been called “Meimei” all our lives, by different generations, and that felt so elementally binding and unchanging.

JT

Can you talk about the experience of writing in multiple genres and about the genre journey you took with Bestiary?

KMC

I’ve always written in multiple genres, but prose, with its tendency toward plot and cohesion, intimidated me. Then I realized my poetry was becoming increasingly narrative, that there was some part of me that would always return to myth and oral storytelling. I sought out prose that was formally wild—like Marilyn Chin’s Revenge of the Mooncake Vixen and Sandra Cisneros’ Caramelo—and I thought, maybe I can do this! There’s a moment in Caramelo when the narrator is speaking and suddenly the grandmother interjects in bold text. I was so shocked and delighted by this interjection, this total disruption of an established “voice,” that I immediately started writing. There didn’t have to be anything “stable” about a narrator—I discovered that porousness. I loved that Caramelo incorporates footnotes and biographical texts and all these other non-fiction-y tones, and that each section reads like an entry. When I first began Bestiary, I thought of it as a collection of pieces tenuously connected by their use of magic and animals. It was only later that I began to realize the pieces were flowing into each other in a specific order and that I needed to be intentional about it. Maxine Hong Kingston’s China Men and The Woman Warrior, their flexibility/irreverence with regard to genre and thought, were guides as well.

JT

Your mention of plot and cohesion reminds me of Yiyun Li quoting her teacher, Marilynne Robinson: “I can’t teach you how to plot a novel but I can teach you how to write a novel without a plot.” What are your thoughts on plotless novels, the relationship between plot and cohesion, and perhaps other forms of cohesion a writer might use in lieu of plot?

KMC

Wow, this is amazing! I make fun of myself for not being able to write a plot, and sometimes I wonder if I can “qualify” as a prose writer if I don’t think about plot very much. My friend Pik-Shuen Fung sent me an article by Joseph Scapellato about thinking of a story’s shape rather than its plot. I loved this idea of story shape because it made me think about the epigraph by Li-Young Lee that I chose for the book: “The name of the river is what it says.” I was drawn to the idea of a river speaking its own name, reclaiming itself. It made me think about Taiwanese indigeneity and how the bodies of water and land had their own names before they were given their Japanese and Chinese colonial names. I wanted to write a story that allowed the river to say its own name.

As I was shaping the book, I thought about rivers and their shapes—meandering but with momentum, forging paths, carrying things along, sometimes violent or flooding or unpredictable, moving through and toward something. I wanted the book to feel riverlike, snaking. That’s not a plot, but it gave me permission to pursue digressions and allow the language to have a will of its own. Sometimes what we define as plotless is just a non-Western way of telling a story. I remember reading Pu Songling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio and feeling so surprised and thrilled by the missing conclusions, inexplicable incidents, and playful digressions.

JT

Tell us more about your beginnings as a writer. How and when did you come to writing? What motivated you to write?

KMC

In grade school, I was an obsessive journal-writer. It felt very illicit to write in my journal at night in the bathroom while everyone else was asleep. When my aunt found out, she was worried that my not-sleeping would stunt my growth. Because of that, I always thought of writing as a physical and embodied act and wondered if the writing was directly linked to how much I grew. Ten-year-old me decided to sacrifice height for writing! All the women in my family were oral storytellers and I recorded a truly stunning amount of gossip, school drama, and myths in my diaries.

What I loved about diary-writing was that I could completely efface myself. The entries were in first person, but the narrator wasn’t the main character: she was the one obsessively observing and recording (and occasionally slandering or lying about) her family. That was typical of the stories my family told: the person telling it was not the main character. The story was always about other people’s lives and what the teller had inherited from them. I loved that there was no differentiation between a story told to a child versus a story for an adult, no sense of scale or tailoring to audience: the stories all had elements of playfulness and grotesque violence. Everyone could laugh at a poop joke and confront their own deaths in the same sentence.

JT

I’m intrigued by your early love of self-effacement. Many young writers turn to the page to be seen, not effaced. What was the appeal of self-effacement for you?

KMC

I’m still trying to understand why a first-person effaced narrator is the mode I always reach for, especially for short stories. The narrators I’m often interested in are the ones that are obsessed with watching and witnessing, and through those obsessions they are made visible or legible to themselves. Part of it might be because queerness for me has often been about disappearing into desire, or not taking direct ownership of that desire. I’m fascinated by narrators who imagine lives in extreme detail but with themselves redacted. My former professor Rattawut Lapcharoensap, who is incredibly generous and brilliant, once told me that my narrators feel like they’re in the eye of a storm. That really stuck with me, not only because I often felt that way, but because I wanted to delve into events or behaviors that may seem inexplicable or wild or pathological but that actually have a source. I wondered if a narrator could be a stormwatcher who sees and names the material conditions that created the storm, who tries to find language for what’s causing it.

I also love effaced narrators because I’m used to stories being told that way. I remember reading the novel Red Sorghum by Mo Yan, in which a son begins narrating and doesn’t mention himself until many pages later. Instead, he unravels the story of his father and grandmother. It’s similar to the way my family tells stories—obsessed with premise. Before getting to the self, you have to first account for what made you possible. This approach completely subverts the idea of a blank slate or that the historical conditions you were born into are merely backstory.

JT

Your use of juxtaposition—high and low, bitter and sweet, dark and light, poop jokes and death—is thrilling. Were you born with this impulse or is it something you’ve learned how to do?

KMC

The impulse might be related to the stories I heard growing up; there was always room for crudity and beauty within the same story. As a kid, my favorite story was Hu Gu Po, about a tiger woman who eats children after impersonating their grandmother. The detail I always think about is that she ate only the children’s toes, and she called them peanuts. Toes as peanuts—it was weirdly endearing to me. I imagined the tiger woman snacking on children’s toes while going about her day and felt this strange sense of affection for her. Something about the peanuts details prevented her from being purely villainous or metaphorical. That mix of humor and darkness always snags at me and urges me to explore stories more deeply. I’ve always thought of laughter as complex, light and dark.

Even traumatic histories were told with an element of lightness. For example, in Taiwanese, waishengren (descendants of post-1949 immigrants from China) are called taro roots, ou-ah, and benshengren (Han Taiwanese people who immigrated much earlier during the dynastic era and consider themselves “natives”) are called yams, han-ji, and so I’d hear all these stories about the deep-rooted conflict between taro and yams, and I thought that these two root vegetables were actually fighting each other under our feet. It imbued the heaviness of historical stories with a strange and jarring sense of playfulness.

JT

Do you have a sense of an audience when you write? Who do you hope will read Bestiary? With whom are you in solidarity here?

KMC

I always hope that Bestiary will reach the queer and Asian diaspora, especially indigenous Taiwanese diasporic folks. On a broader level, the book was also my homage to so many Asian American women writers whose books have allowed me to imagine my own future and past, specifically Maxine Hong Kingston, Jessica Hagedorn, Marilyn Chin, Hualing Nieh, and many others. In Hua Hsu’s New Yorker profile of Maxine Hong Kingston, she says that she wrote a particular scene of her grandfather in order to give herself a grandfather who would love her as a girl, as a daughter. That moved me to tears and broke me a little, too. It made me realize that I could be an audience of my own work, that by writing I was also trying to give myself and my younger self the love she was looking for.

JT

There’s a marvelous passage from Bestiary that I’d like to quote here for our readers:

…I wanted to taste everything native to her. I held her spit

in my mouth, wondered if this was what the teacher meant

by exchanging bodily fluids. We’d just begun seventh grade

sex education, which mostly meant our teacher explained

that the adhesive “wings” of a Maxi pad were not literal wings

and could not equip us with flight. The teacher told us to de-

velop a platonic relationship with our bodies. On the list of

illicit fluids that could be exchanged, bartered: semen, vagi-

nal discharge, blood. But there was nothing about what we’d

done. In the animal encyclopedia Ben and I memorized, every

hierarchy had a name. Every violence a vocabulary. Some-

where, there was a name for our exchange, in a language that

was kept from us.

To me, this is signature Chang. Sexy, funny, unflinching, deeply felt, a moment that at once empowers and reveals pain. The passage highlights the intersectional nature of gender, sexuality, power, language, and culture. Can you tell us more about this?

KMC

I love that you chose this passage because it’s one of the few that didn’t change from the original draft! It felt to me like one of the central scenes of the book—a moment of playfulness and reckoning. While writing the book and its oral histories, I thought a lot about canonical and “authoritative” texts and ways to subvert or play around with these. To me, Ben is a character who embodies playfulness, wonder, and irreverence for text and language. The narrator is seeking a vocabulary for her desire, but it doesn’t exist where she looks for it, and it isn’t given to her either. It’s embodied in her interactions with Ben, who so willingingly and eagerly invents her own language, who shows Daughter that the texts they’ve been given are encoded with power and hierarchy and that there are possibilities outside of that, that the language they’ve been looking for is already being articulated internally through their bodies.

JT

JT: I feel I would be remiss if I didn’t ask you about our girl heroine’s powerful tail! Why the focus on the tail? What inspired you?

KMC: I love this question! On a very simple level, I love the wordplay of tale/tail—it’s the kind of thing the ten-year-old me who was writing rhymes and little word games would have appreciated, and it hints at the tales/tails she’s inherited. I was interested in the tail as a snake-like, even phallic, species. Snakes and other winding, twisty, knotted creatures appear in the book and in mythology as foreboding, feminine, and sometimes sinister. I was interested in her tail as a semi-autonomous snake-like creature she both tries to wield and cannot control. I also thought about the repetitions of tether and tethering, how the tail is a leash or rope, rooting her within her family and at the same time allowing her to be tugged into dynamics or violence that she can’t or doesn’t want to escape.

JT

Daughter’s aunt, Dayi, speaks one of the most haunting lines in the book: America is a kind of after life. Ben echoes this sentiment when she tries to reassure the speaker: We’re not alive. We’re just between deaths right now. These remarks foreshadow the moment when the doctor asks if the family has a history of heart disease and the mother replies, “…no, we have no history, just stories, just a long record of surviving our countries.” I’d love to hear you elaborate on these lines and the nuances of their overlapping.

KMC

KMC: Thank you for highlighting these lines! I was thinking about the goddess Mazu—the chapter about Dayi is named after her—and how she has the divine ability to project herself in her dreams and save sailors from drowning in the sea while still sleeping at home, safe, not truly risking herself. This idea of an astral projection, a living ghost that comes in and out of your body, was so interesting and haunting to me. I thought of the way in which the characters didn’t necessarily want to “give” themselves to a country, or wanted to exist in multiple places at once, how Daughter sometimes feels that she’s interacting with the ghost of someone rather than interacting with their physical bodies, or that her aunt exists in multiple places at once, and the one in America is a ghost of her other self. History and story interact and contradict each other in so many ways—familial stories and anecdotes are considered unofficial, subjective, non-authoritative, while the “facts” are seen as solid, unmoving, real—but for me it felt like the opposite, that the stories and anecdotes and records of meals or rituals of grief were what felt real, and the facts felt like fabricated containers.

JT

This tension between unofficial stories and “fact” reminds me of another doubleness in Bestiary. Like the moon and the sun Ama speaks of, speech is the corpse of silence and vice versa; they are a double yolk. One of them is always setting while the other rises. Can you talk about your book’s relationship to this perpetual rising and setting, to silence and speech?

KMC

Wow! I hadn’t thought of this before, but I love that you’ve drawn out the image of the double yolk. I wanted to explore silence as its own living, breathing thing that isn’t the same as absence or a void. Silence as something deliberate, as defiance or refusal, an active choice. The grandmother’s sections and the silence that lives between her fragments—to me, those silences aren’t erasure or censorship, but a deliberate refusal to be understood in a linear way, a purposeful interference. It felt a bit rebellious to me while I was writing it—like oh, she wants us to labor through these letters! She wants us to puzzle things together, to fail, to fall into these holes. She’s wielding her silence like a language. The rising and setting idea was really interesting to me too, in relation to the Tayal myth of the multiple suns, which is similar to the Chinese myth. There’s so much reverence for light in Western literature. I was interested in a hero who brings darkness, a relief from so much light—the idea that setting is as important or even more important than rising, which challenges the colonial idea of the rising sun as empire and “progress.”