Her teeth and nails turned to grit, and she became part of the earth itself.

November 30, 2020

Once, in a city on the coast, a man had three daughters.

The first daughter was soft, and sweet, and a wonderful cook; she danced through the kitchen leaving a trail of coriander in her wake. “You eat enough food to feed this whole family,” Father told her. “You know the village I come from? You eat enough food to feed that village.” He would watch carefully as the girl served herself rice. He shook his head when she emptied her plate once, twice. He ate barely anything himself, tucking one or two pieces of squash under his tongue, and as she grew tall and strong, Father grew frail.

“If you keep eating like this, you’re going to starve your sisters,” Father said. “I’d better find you a husband before you eat us alive.” Many suitors came to see the girl, and Father finally chose a well-educated and ambitious young man who flew her away to America after the wedding.

In America, the first daughter found porridge studded with winter-berries, noodles cooked in cream and butter. Her husband was a well-off man, and showed his wealth with expensive meals and luxurious foods. He watched his wife empty her plate once, twice, and hoped she might already be pregnant. He resolved to fill her stomach with meat and fat, spice and oil, to ensure the birth of a boy-child. As he stocked the pantry again and again, enough food to feed an army of healthy baby boys, the first daughter found herself satiated. In fact, she was very full, but her husband insisted she keep filling her stomach.

Soon the grocery store aisles were bare, the local markets shut down. The farmers wrung their hands, helpless. Then the husband led the first daughter outside to find more food. He had her pluck fruit from the neighbor’s trees, and when the trees were bare she ate the leaves, the branches. He had her catch fish with her hands, and when the pond was empty she gulped the water, the weeds.

Still, the husband was not satisfied, and the first daughter saw his displeasure. So when he pointed upward to the sky, she reached an arm up and pulled the sun into her mouth. Her stomach inflated, her skin stretched, her body swelled so wide that she became the sky itself—and the sweat from her pores fell as rain, her wet breaths puffed into clouds, the hair shedding from her legs was caught in the wind and flew like blackbirds in the breeze.

The second daughter was an irritable sort. “I could use your tongue to sandpaper my knife,” Father said. “I’d better find you a husband before we get run out of town.” The man he found was a young associate overseas, a modern type who found amusement in the girl’s coarse manners. After the wedding he flew her away to Dubai where he worked.

In Dubai, the second daughter found the heat baked her inside out. The sand wore away at her skin until it cracked like uncured leather. Her heels bled into her thin-soled slippers. She rubbed herself down with sweet-smelling lotions, hoping to please her husband. She plaited her hair with almond oil, coated her lips in lard, but she could do nothing to make herself more supple or slick. Whenever she left the coolness of the house to go to the market, the sun would dry her out, her bones desiccating inside her. The sand was everywhere—it collected in her shoes, dusted her hair like dandruff, settled in the lines of her face, falling out only when she smiled or frowned.

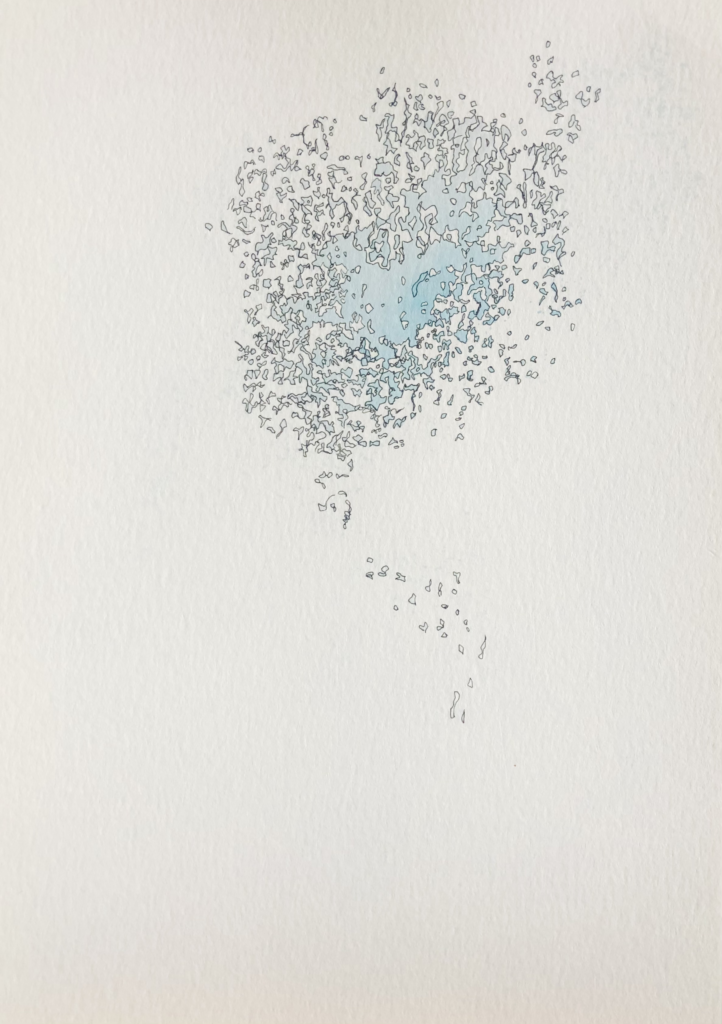

Finally, her husband, who had once laughed along with her hoarse voice, grew tired of his dried husk of a wife. He laid a fist to her, and she found that she was brittle and rough after all, just like Father had said. The second daughter exploded like a sandcastle all over the living room carpet. Her husband tracked through her on his way to work and carried her off on his shoes. On the way out, she mixed in with the dunes and grass. Her teeth and nails turned to grit, and she became part of the earth itself.

The third daughter was a quiet sort, her face shaped like a lotus leaf. She had watched her two older sisters escape to distant lands, and she was biding her time.

Father told her she was a stupid girl. “You’re always so silent, there’s nothing much in that pretty head of yours,” he said. “It’s a good thing you’re so quiet, your idiocy would be revealed if you opened your mouth.” But it was not fun to torment such unresponsive prey. He had planned to keep the third daughter unwed for a little while longer, as he did not want to be left all alone, but his irritation made him hasty. So he found the first man who would take this soft-spoken girl, and soon she found herself married and flying away to London.

By daybreak, she became familiar with the distinct red outline that her husband’s hand could leave against the skin of her left cheek.

In London, the third daughter discovered that her husband was an important person, a businessman with a fancy office and a shiny car. His friends threw grand parties, and all the men brought their charming wives, who dressed in gowns of crushed silk, wore red on their lips and diamonds at their ears. They were unselfconscious, chatting to each other softly, and when the third daughter found herself in such a circle, she grew flustered. Her husband pinched the small of her back, encouraging her to be as charming and red-lipped as the other wives, but the third daughter found that after years of silence, she now could not gather her voice to speak.

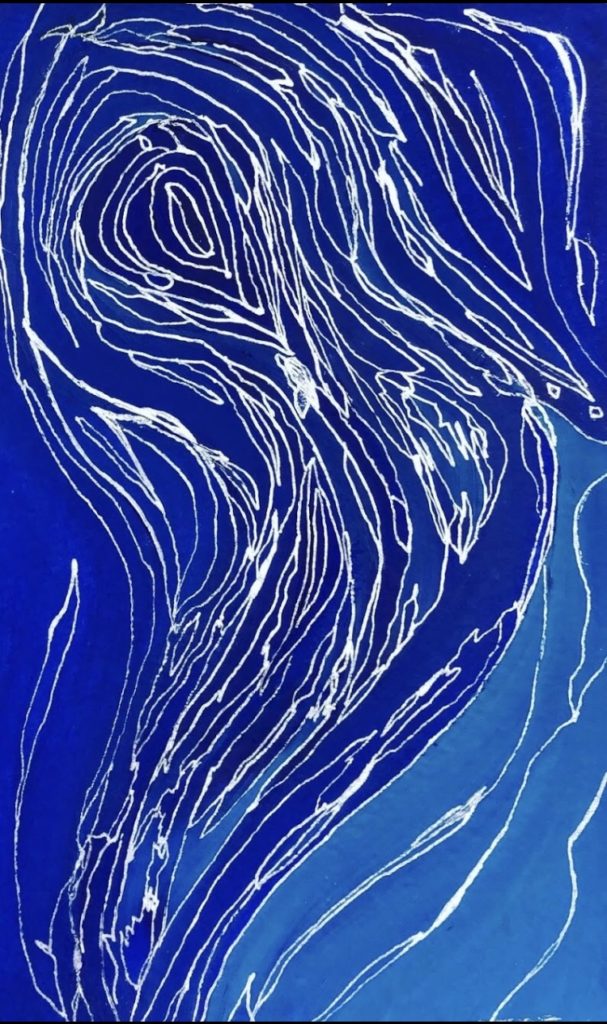

When the third daughter went home that night, she knew what was to come. By daybreak, she became familiar with the distinct red outline that her husband’s hand could leave against the skin of her left cheek. Like her two sisters, the third daughter knew the shape of a man’s anger. The next morning, as her husband left for his important job in his shiny car, she packed a bag. She left. She walked through London, past the glass-fronted stores filled with pearls and jewels, the iced necks of velveteen mannequins. She walked until city turned to town and village turned to countryside. Finally, she found a densely wooded area—a forest, not quite like the warm and sticky greenery of her home, but still lush and densely populated with creatures of the earth. There she chose to sit down, finally, to rest.

The third daughter sat very still and very quiet for a very long time. She grew moss in between her toes, her skin turned fuzzy and brown like the peel of a ripe chiku. She sat so still that small animals climbed around and over her, built their homes in the warmth of her crossed thighs. The birds plucked hair from her head for their nests until she was left as bald as a newborn child. Her eyes grew glassy with the reflection of the trees. Her pupils dilated in the darkness of the foliage, until her wide-eyed look resembled that of some woodland creature. Her tongue withered from disuse, until she was as speechless as the animals that skittered around her, and they claimed her as one of their own. The third daughter lived for many long years in this way. When she died, they ate her flesh and gnawed at her bones, and she became a part of them.

The father knew nothing of what happened to his three daughters. “You can’t expect a daughter to call too much after marriage. They have their own houses to look after now,” he said. He kept chickens, and grew a garden of holy basil and tiny sour tomatoes to stay busy. He tended to the apathetic hens that only laid eggs when they felt like it. He cried for his daughters, not knowing how far they had travelled into the world.

“Does a father call his own children, begging for their time? If they had any respect for their elders, they would call me,” he said, but he still waited by the phone out of habit for years, until he eventually forgot what he was waiting for.

He cursed the unrelenting sun that made him sweat, and the sky that hurt his eyes with its brightness. He cursed the dry soil that made his plants droop and wither, and the rabbits that loved to nibble his herbs, and he cried quietly for his loneliness. Storms came, droughts passed, and the sun rose and set with indifference to human affairs.