Looking to Jose Rizal and Carlos Bulosan to speak to our present

September 10, 2020

Editor’s Note: The following essay is part of a series on The Margins responding to the idea of unfreedom and the continuous and connected struggles for freedom globally. Look out for more in the series in the coming weeks, and watch “The Sweat of Love and the Fire of Truth: A Reading,” our event featuring writers who reflect on freedoms, whether they be collective, practiced out in the world, or of the body and mind.

Swarms of locusts in East Africa.

Hurricanes battering the Caribbean and the Atlantic seaboard.

Earthquakes and floods in Pacific Rim nations.

Polar ice caps melting.

And now COVID-19’s evil god raging globally, insatiable in its hunger for mortals. Do these afflictions of biblical proportions signal that the end days are here, or simply the end of normalcy as we know it?

Like countless others, my wife and I have been sheltering in place for months, venturing forth occasionally for shopping and walks in our Jackson Heights neighborhood. Taking the subway is tantamount to an expedition into uncharted territory. Watching the news becomes an exercise in unwanted masochism: simultaneously not wanting and yet needing to witness the train wreck of an utterly incompetent, narcissistic, and criminally liable President unwilling or unable to shape national policies that will stop the spread of COVID-19. He bills himself as a wartime President. Fine. In which case he should be sacked for unforgivable dereliction of duty.

With the economy in a disastrous tailspin, and the glaring fact of systemic racism highlighted by the Black Lives Matter movement, anyone who at this juncture still believes in Trump’s mental sagacity simply because he identified an elephant (but deliberately avoiding mentioning the elephant in the room, namely the spread of the virus), in his being “cognitively there,” brings into question their own cognitive health as well as their ethical and moral selves.

Something similar can be said of the admirers of the thuggish Duterte of the Philippines, and for that matter, Bolsonaro of Brazil, Orban of Hungary, Lukashenko of Belarus, Xi Jinping of China, and Putin of Russia. Imagine them in a police lineup, and we victims of their crimes are asked to finger the guilty party. No brainer: all are guilty!

This pandemic has exposed long-standing fault lines, forcing us to pay close attention to the resurgence of fascism. The virus of racism. The malady of unchecked capitalism, with the ever-widening gap between the haves and have-nots. The spectre of despair and drug addiction, with the abuse of opioids on the rise.

How to make sense of this global misery, this Pandemonium (the name Milton gives to the capital of Hell in his epic poem Paradise Lost), the prevalence of a dog-eat-dog worldview, of misanthropy?

One key, though not the only one, is race, as the Black Lives Matter movement makes crystal clear. Within the context of capitalism, with its devotional obeisance to the free market, and thus to individualism, the color of one’s skin almost always shapes or configures the class one belongs to. Whatever examples one might point to as a counter-argument—but there are wealthy Blacks and browns!—pales beside the unforgiving reality of percentages that will make you weep and gnash your teeth: the highest-earning 20 percent of U.S. households (with incomes of at least $130,001) bring in 52 percent of all U.S. income, more than the lower four-fifths combined, according to Census Bureau data. And of that 20 percent, 1 percent has 20 percent of the nation’s wealth.

In the mecca of capitalism, U.S. income inequality is the highest of all the G7 nations, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

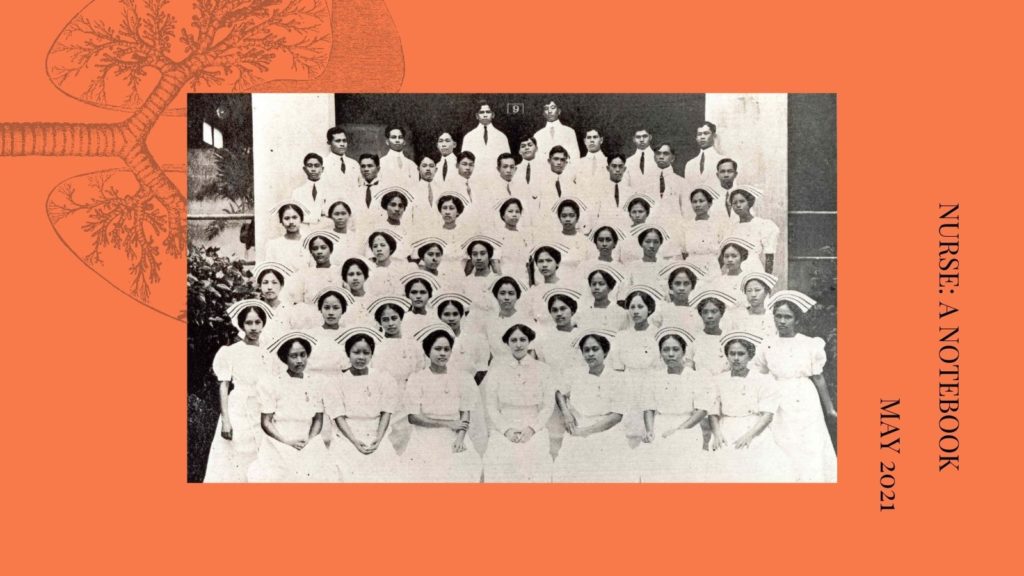

Race means that communities of color have been hit the hardest by the pandemic. African Americans are three times more susceptible to the virus than whites, six times more likely to be hospitalized, and twice as likely to perish because of COVID-19. And from communities of color come a majority of those workers deemed to be essential, and here I take that term to include not just doctors and nurses, but also all those who maintain the health infrastructure so necessary in this ongoing battle, EMT personnel and behind-the-scene workers who cook and clean hospitals and clinics.

The impact of COVID-19 on Filipino nurses is especially revealing. According to Dr. Leo-Felix Jurado of the Philippine Nurses Association of America, out of the 4 million registered nurses in the United States, 4 percent, or 160,00, are Filipino. “Most of these nurses are found in five states particularly,” said Dr. Jurado. “Hawaii, California, New York, New Jersey and Texas.”

The majority of Filipino nurses are likely to work at people’s bedside, in acute and critical care. “As a result of that,” he says, “we have seen more impact of the COVID-19 pandemic [on] our nurses. Many of our nurses have contracted the virus, [and] many … have resulted in fatalities,” said Jurado. Extrapolating from deaths among the nurses puts Filipino Americans at a 40 percent mortality rate, significantly higher than the overall 3.7 percent mortality rate in the U.S., according to recent research by Johns Hopkins University.

In stark terms, race helps determine class.

Can class help determine race? It might seem a nonsensical question—does being poor render someone Black or brown?— but logic gets thrown out in the face of prejudice. Take the Irish: When the mainly working-class migrants arrived in this country they were seen as Black, for “blackness” can be a political marker as well as a racial one. Being for the most part Catholic, the Irish did not fit within the neat parameters set down by the ruling class—White Anglo-Saxon Protestants, or WASPs.

Whatever lay outside the box was darkness, beyond the pale. Only as the Irish rose through the economic and political spheres did they start to lose their “blackness” and reclaim their “whiteness,” their skin tones growing paler as they ascended in class. An increase in their consumer power miraculously restored their whiteness.

Race, as the British Marxist Stuart Hall wrote in 1978, “is the modality in which class is lived” as well as “the medium in which class relations are experienced.” While capitalism in its pure form may seem to be color-blind, the truth is, market forces don’t operate in a vacuum. Within the neoliberal structures of U.S. society, who controls the market forces determines levels of income. And with race a factor in ascertaining who the power holders are, income inequality results, most markedly in communities of color. That inequality is as astounding as it is depressing, as indicated by the figures I cited earlier.

In the context of Philippine colonial history—and I daresay of any colonial history—the intertwining, indeed the inextricability, of class and race, is plain to see. Understanding that history helps us understand, though not completely, the urgency of the Black Lives Matter movement and its relevance to our lives and our history here in the United States. And by “our” I do mean everyone’s life, everyone’s history, irrespective of race and ethnicity.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

Time and again I find myself returning to Jose Rizal’s novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo as a way to understand certain complexities of the present. The Noli is particularly rich in the way that class and race are examined through its characters. In the social hierarchy of Las Islas Filipinas, being a Spanish colony, the peninsulares (those born in the Iberian peninsula) were the crème de la crème; the insulares (Spaniards born in the colony) and the mestizos (a mixture of Spanish and other blood) only slightly below them. Many Spaniards sought better lives and fortunes within the Spanish Empire, mostly in South America and in Mexico. A few ventured further, to the Philippines. An ordinary peninsular, really a nobody back home, could find himself (and the emigré was almost always male) propelled to or near the top once he got to the colony.

I can think of no better illustration of this than the Noli’s lame Doctor Tiburcio De Espadaña, the quack doctor from a proletarian background in Spain who, once in the archipelago, is able to pass himself off as a learned and esteemed medico, given tacit support by his fellow peninsulares who would have deemed it an embarrassment to have one of their own actually earn his bread honestly, like the indios did. He may have been lame but his being Spanish is all the attraction needed for the wealthy native Doña Victorina to eagerly make him her husband (and not the other way around). The Doña is one of those misguided souls who blithely disregard being kayumanggi, or brown-skinned, considering it a hindrance, and comport themselves as though they were members of the colonizing, hence, superior, race.

Her male counterpart is Kapitan Tiyago (Captain Santiago de los Santos), another wealthy indio who somehow bizarrely gets to be the Secretary General of a rich society of mestizos, “despite protests that most people did not consider him as such.”* His delusion is so complete that when “someone criticized the mixed-blood Chinese or Spanish merchants, he would criticize them as well, because he considered himself a pure Iberian.” He is keen for his beautiful daughter Maria Clara to marry Crisostomo Ibarra, the novel’s protagonist, who is a genuine mestizo, and wealthy to boot. Victorina and Kapitan Tiyago don’t avoid race so much as embrace it, though it be the wrong kind, in order to retain and increase their wealth and status. Doña V goes to ridiculous lengths:

She added a “de” to her husband’s name. The “de” didn’t cost anything, and gave a certain something to the name. When she signed it, she put Victorina de los Reyes de de [emphasis added] Espadana. This “de” was a mania. Neither the man who engraved her cards nor her husband could get the idea out of her head.

— From the Harold Augenbraum translation of Rizal’s novel, Penguin Classics edition, 2006.

In the novel’s most hilarious scene, she gets into a catfight with Doña Consolacion, the india wife of the Guardia Civil lieutenant, who like Tiburcio, is a peninsular. Consolacion has racial fantasies similar to Victorina’s. Since like repels like, both trade insults, betraying their class backgrounds and aspirations.

So many modern-day Victorinas, Consolacions, and Kapitan Tiyagos continue to live in our midst. I’ve met more than my share and I’m sure the reader has, too. But the one who most reminds me of Rizal’s faux Iberians is one I have never met: Michelle Malkin. She is a brown-skinned, wannabe-white right-winger Filipina-American who identifies with Neo-Nazis and other white supremacists. Even though she has her US citizenship precisely because she was born here to Filipino immigrants, she nevertheless advocates for the abolition of birthright citizenship.

This racist dog whistle regarding birth has been repeated by Trump, who shamelessly peddles groundless doubts about Senator Kamala Harris’s citizenship—born in Oakland, California—, just as he did regarding Barack Obama’s. Recently, Malkin was included in a series that runs in the liberal online journal, Positively Filipino, titled “Remarkable and Famous Filipinos,” written by Mona Lisa Yuchengco, the journal’s publisher. In Yuchengco’s preface she states that the series aims “to give you weekly short biographies of famous Filipino American role models [emphasis added] and achievers … those who continue to make us proud to be Filipino, regardless of their religious and sexual orientation and political flavor.”

Role model? Once, when she was described as “the Asian Ann Coulter”—the blonde right-wing activist who, among other things, worries that whites will no longer be the majority by 2050 and who supports the display of the Confederate flag—aside from saying she was flattered by the comparison, Malkin declared, “I am not Asian, I’m American.” Proud to be Filipino she ain’t. And, one can safely assume, neither is she enthusiastic about the Black Lives Matter movement.

Famous? I suppose in certain circles she is, for identifying with Holocaust deniers, for which she was dropped by the conservative organization, Young America’s Foundation (YAF). In 2004, she defended the U.S.’s internment of 112,000 Japanese Americans during World War II, an egregious violation of their civil rights. Malkin saw in that a justifiable precedent for treating Arab- and Muslim-Americans in the same manner post-9/11. That Positively Filipino portrays Malkin as a model for the younger generation to emulate is a head scratcher.

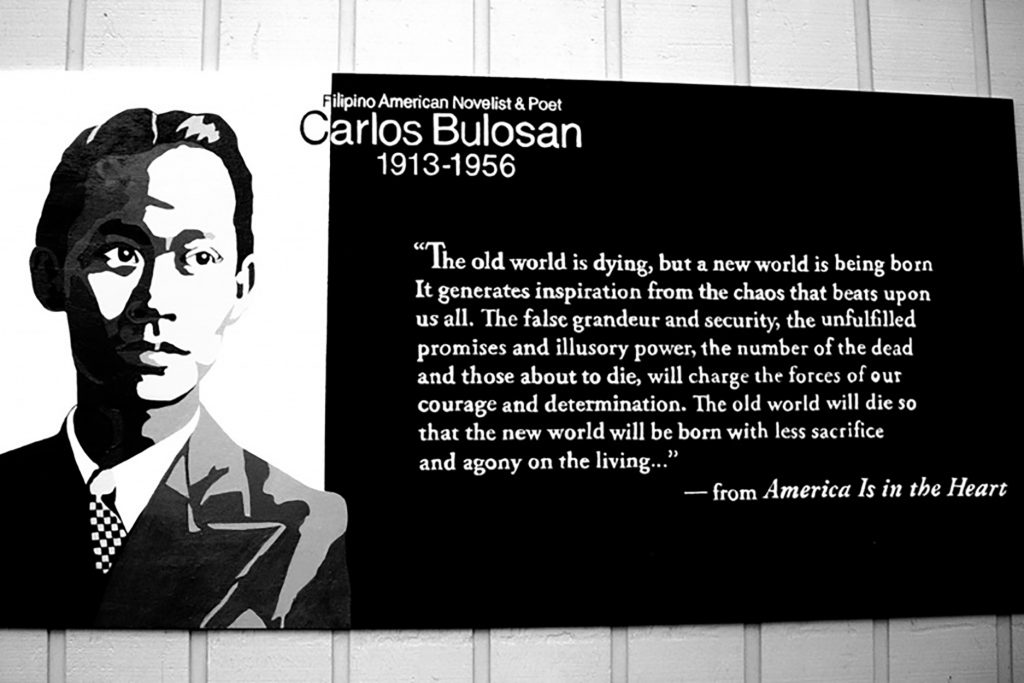

Nevertheless, in a perverse way, the fact that this ethnic Filipina can even take a stance publicly as though she were white is a measure of how far we have travelled as a people of color (though not far enough)—a far cry from the pre-civil rights era that Carlos Bulosan and his fellow manongs belonged to, when being Filipino was tantamount to a crime, as Allos, Bulosan’s doppelgänger in his classic America Is in the Heart, despairingly notes.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

In 1943, as World War II was raging, Bulosan was commissioned by The Saturday Evening Post to write an essay on one of four freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear, based on Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” speech delivered before Congress in January 6, 1941, almost a year before Pearl Harbor. Bulosan was asked to write on freedom from want.

The four essays were to accompany the popular magazine’s publication of Norman Rockwell’s series of paintings over four successive issues: February 20, February 27, March 6, and March 13, 1943. Other than Bulosan, the other writers commissioned were Booth Tarkington, Will Durant, and Stephen Vincent Benet. That Bulosan was the only person of color among the four was amazing given the deep racial prejudice of the era. It helped that the Philippines was a U.S. ally in the fight against the Japanese. Too, Bulosan had gotten some critical acclaim for his poetry and short stories. Just the year before, on December 19, 1942, The New Yorker published a short story of his, “The Laughter of My Father.”

In all likelihood he was the first Filipino writer to be published in the prestigious magazine. He had had some of his poems published in Poetry, the seminal literary journal founded by Harriet Monroe and whom he mentions in America Is in the Heart, published in 1946, shortly after war’s end.

Given the protests taking place today all over the United States, his words are still eerily accurate:

We are bleeding where clubs are smashing heads, where bayonets are gleaming. We are fighting where the bullet is crashing upon armorless citizens, where the tear gas is choking unprotected children. Under the lynch trees, amidst hysterical mobs. Where the prisoner is beaten to confess a crime he did not commit. Where the honest man is hanged because he told the truth.

Bulosan recognizes that it isn’t just the needs of the body that must be met, but those of the mind and soul as well. His essay could have been easily subtitled, “A Want of Freedom.”

“But our march to freedom is not complete unless want is annihilated. The America we hope to see is not merely a physical but also a spiritual and an intellectual world. We are the mirror of what America is. If America wants us to be living and free, then we must be living and free. If we fail, then America fails.

Bulosan’s admonition, that “if we fail, then America fails,” implying a collaborative and inclusive society, is echoed more memorably in the concluding passage of Part II of America is in the Heart, when Allos recalls his older brother Macario’s stirring paean to the dream of America:

America is not merely a land or an institution. America is in the hearts of men that died for freedom … America is also the nameless foreigner, the homeless refugee, the hungry boy begging for a job, and the black body dangling from a tree. America is the illiterate immigrant who is ashamed that the world of books and intellectual opportunities is closed to him. We are all that nameless foreigner, that homeless refugee, that hungry boy, that illiterate immigrant, that lynched black body. All of us, from the first Adams to the last Filipino, native born or alien, educated or illiterate—We are America!

Carlos Bulosan may have been a poor brown probinsyano (country hick) from the northern Luzon town of Binalonan but he was undaunted by the barriers of class and race that must have seemed insurmountable at that time. Active in the labor rights struggle, particularly among the farm workers, beginning in 1950, he was a target of FBI surveillance, the feds suspecting him to be a threat to U.S. national security.

This was at the height of the Cold War, a time when McCarthyism spawned a virulent hysteria that saw liberals, progressives, and activists as Communists and/or undercover agents of the Soviet Union bent on subverting America’s democracy. FBI surveillance ended in 1956, with Bulosan’s death at the too-young age of 43 from bronchopneumonia, a toxic legacy from his being stricken earlier with tuberculosis.

Today, with the Trump administration’s continual denigration of immigrants, specifically immigrants of color, once again we see a deliberate stoking of nationalist cum racist sentiments that would have been all too familiar to Bulosan. He would most certainly have recognized the dangers they pose to the vision of America he articulates in his writing and is embodied in the words of the U.S. official seal: E pluribus unum. Out of the many, one. He would absolutely have been a staunch ally of the Black Lives Matter movement—a proud brown man, standing along his Black brothers and sisters, peacefully marching with them, with Asian Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and white allies, speaking truth to power. Containing Whitman’s multitudes, “from the first Adams to the last Filipino,” he would have been down with the many.

* KKK in the illustration above stands for Kataas-taasan, Kagalang-galangan Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan, which translates in English as The Highest, Most Noble Association of Children of the Nation.

If this essay could define freedom or unfreedom: “Freedom is the oxygen of democracy. Right now that freedom, especially for people of color, is imperiled. As both a writer and a citizen, I am compelled to act, with my pen as my weapon of choice, just as Carlos Bulosan in 1943 took his up to write ‘Freedom from Want’ so prescient and that still speaks so eloquently to all of us.”